The myth of Volcker’s 1979 assault on inflation

Commenter Russ Anderson pointed me toward a Fed publication that discusses the Volcker disinflation:

Twenty-five years ago, on October 6, 1979, the Federal Reserve adopted new policy procedures that led to skyrocketing interest rates and two back-to-back recessions but that also broke the back of inflation and ushered in the environment of low inflation and general economic stability the United States has enjoyed for nearly two decades.

This may be technically accurate, but it’s highly misleading. It creates the impression that Fed policy became contractionary in 1979 and that this gradually broke the back of inflation. But this simply isn’t so; monetary policy during 1979-81 was highly expansionary, as evidenced by rapid inflation and NGDP growth. The Fed only because serious about inflation in mid-1981, when it raised real interest rates sharply. This immediately broke the back of inflation. So much for long and variable lags.

The picture is complicated by two factors that seem to support the official narrative:

1. Monetary policy was briefly tightened in late 1979 and early 1980.

2. There was a brief recession in early 1980.

Both of those facts are true, but highly misleading. The tight money of late 1979 was not really all that tight, and it lasted very briefly. By late-1980 monetary policy was highly expansionary, indeed perhaps the most expansionary in my lifetime. Only in mid-1981 did the Fed seriously commit to tight money.

The recession of early 1980 was the shortest and mildest recession of the post-war era. And it occurred against a backdrop of deindustrialization in the rust belt, and punishingly high taxes (MTRs) on capital. The unemployment rate rose to a peak of 7.8%, but it was nearly 6% during the 1979 boom, evidence that President Carter’s bad supply-side policies were hurting the economy. In addition to high tax rates, we had energy price controls.

Although the recession officially began in January 1980, RGDP actually rose in the first quarter. As late as March 1980 few expected a recession, the economy seemed to be in an inflationary boom. Yes, the Fed raised the discount rate from 12% to 13% in mid-February, but about the same time the January CPI numbers came in at an 18% annual rate. Gold peaked at $850 in January. Thus in mid-March Carter put credit controls into effect to try to slow the economy and this pushed RGDP down at a 8.4% rate in the second quarter. Soon it became clear we were in recession, and the controls were quickly phased out. The recession was over by July, and housing and auto production recovered quickly. Nevertheless, during the ensuing recovery unemployment leveled off in the 7% to 7.5% range, despite ultra-easy money.

I’m probably the only person who’s ever called monetary policy during 1980-81 “ultra-easy.” This is right smack dab in the middle of the infamous Monetarist Experiment of 1979-82, the one that “broke the back of inflation.” But facts are stubborn things.

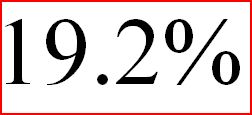

In mid-1980 the Fed panicked at rising unemployment, and cut interest rates back into the single digits, despite 13% CPI inflation during 1980. The result was predictable. NGDP started recovering briskly in the third quarter. But it was the next two quarters that were truly astounding; during 1980:4 and 1981:1, NGDP grew at an annual rate of:

.

.

.

.

.

That, my folks, is easy money. I can’t even recall a faster rate over six months, although I don’t doubt there were some. Think about how NGDP was “recovering” at just over 4% during 2010, and how the Fed huffed and puffed and pushed NGDP growth up to . . . 3.4% so far this year.

Yet this hyper-charged growth in AD did not significantly reduce unemployment. Believe it or not, 7% was probably the natural unemployment rate by 1981. It is not true that tight money cost Jimmy Carter the election. His poor supply-side policies combined with his neglect of inflation produced a high misery index on election day. That would have happened with or without Volcker.

In 1981 Reagan took over and supported Volcker’s fight against inflation. By mid-1981 the Fed got serious, and real interest rates began rising sharply. NGDP growth plunged into the low single digits. During the recovery Volcker did allow relatively rapid NGDP growth, but not enough to re-ignite inflation. Once RGDP growth leveled off, NGDP growth also slowed. The recovery was also helped by Reagan’s good supply-side policies, such as much lower MTRs, energy price decontrol, and a tough stance toward public sector unions. For the first time in my entire life the US began growing faster than most other industrialized countries.

So the 1979 assault on inflation is mostly myth. It was just a blip in the ongoing Great Inflation, which didn’t peak until early 1981, when NGDP growth peaked. Only in mid-1981 did the Fed get serious about inflation, and the results were almost instantaneous. CPI inflation during Sept 1980- Sept. 1981 was 11%, over the following 12 months it plunged to less than 5%. NGDP growth from 1981:3 to 1982:4 was at only a 3.4% annual rate. Why did almost everyone get it wrong? Because almost everyone believes in long and variable lags. And many people focus on nominal interest rates. And because it makes a good story.

PS. You might ask if monetary stimulus today might lead to disappointing results, just like in 1980-81. The answer is no, for reasons I’ll explain in the next post.