Shall we target inflation with fiscal policy?

Most Keynesians seem to think that fiscal policy influences AD and inflation, even when rates aren’t stuck at the zero bound. This recent article from The Economist illustrates the conventional Keynesian view:

Even the lower estimates could easily be enough to tip the economy back into recession. Mr Greenlaw says the closest precedent was in 1968, when individual, corporate, excise and payroll taxes collectively rose by the equivalent of 3.1% of GDP, mostly to pay for the Vietnam war and to damp down inflation. The next year, the economy fell into recession.

Paul Krugman is certainly not a conventional Keynesian; he’s quite dismissive of this sort of old Keynesian reasoning:

People in my camp have repeated until we’re blue in the face that the case for fiscal expansion is very specific to circumstance “” it’s desirable when you’re in a liquidity trap, and only when you’re in a liquidity trap.

In the case of the 1968 tax increases it looks like Krugman is right and Greenlaw is wrong. America experienced 3.1% inflation in 1967. After taxes were raised, inflation rose to 4.2% in 1968, 5.5% in 1969, and 5.7% in 1970. So much for “damping down inflation.” Indeed this was one of the key stylized facts that led to the resurgence of monetarism in the 1970s, often cited by Milton Friedman. You can’t stop inflation by balancing the budget, only monetary restraint is effective. And we had to wait until mid-1981 for a serious effort on that front. Krugman knows this history, and understands that monetary policy drives the economy when we aren’t at the zero bound.

[The very mild recession that began at the end of 1969 might have partly reflected the worsening supply-side condition of the US economy, along with catch-up wage increases as the Phillips Curve shifted right.]

Krugman has a nuanced approach to the question of fiscal vs. monetary policy, which can occasionally go right over the heads of his readers. I bet lots of his fans nodded their heads when reading the quotation I just provided, not realizing that “my camp” might consist of not much more than one member. If I’m not mistaken Joe Stiglitz is much more typical of the Keynesian camp, and he certainly thinks there’s a case for fiscal stimulus when not at the zero bound.

Here Krugman criticizes British austerity:

And given that public investment is, you know, productive, this is almost surely a case of self-defeating austerity: by shortchanging infrastructure now the Cameron government is saving only a trivial amount on interest payments while reducing long-run growth and hence revenues.

Previously I’ve argued that there isn’t much austerity in Britain—in 2011 their budget deficit was nearly the largest in the world. But the bigger problem is monetary policy, which seems committed to targeting some combination of inflation and NGDP growth. Either way, fiscal stimulus is ineffective in the UK, as it’s offset by the BOE doing less unconventional monetary stimulus.

There are times where Krugman seems to acknowledge that monetary stimulus is needed to boost inflation. At least I think he does—see what you think:

At this point an argument that was once considered way out there “” that euro area adjustment won’t be possible unless the inflation target is raised “” now has widespread support, albeit not from the crucial players. Inflation significantly above 2 percent is almost surely a necessary (though not sufficient) condition for the euro to survive.

So what’s happening to euro inflation expectations? We can look at the German breakeven “” the difference in yields between German bonds, presumably viewed as safe, and yields on German bonds indexed to euro area inflation. This currently points to an expected inflation rate over the next 5 years of 1.3 percent “” way too low to make euro survival feasible.

So how has that breakeven evolved over time?

. . .

And what happened in April 2011? The ECB hiked rates, even though it was obvious that the rise in inflation was a temporary blip driven by commodity prices. This was a clear signal that the price stability obsession was as strong as ever. And it has meant, in the end, a loss of hope.

This is exactly right. But what exactly is Krugman saying here? How should Europe raise inflation? Should they use fiscal stimulus, or monetary stimulus? Krugman would support either approach. But unless I’m mistaken he’s referring to the ECB in this post—they are supposed to set a higher inflation target. Now look at what he said just a day earlier:

Simon Wren-Lewis argues that if we’re up against the zero lower bound but are uncertain about the size of the output gap “” how far the economy is operating below potential “” we should deliberately overreach on fiscal policy. Why? Because monetary policy can correct any excess stimulus, but not an inadequate stimulus.

Krugman’s fans will suggest I don’t understand, he thinks monetary stimulus is worth a try, but supports fiscal stimulus because he doubts both the willingness of the monetary authority to stimulate, and the effectiveness of monetary stimulus at the zero bound if they did.

I don’t believe fiscal stimulus can do very much, even at the zero rate bound. But if I thought it could, and if I thought higher demand was needed, I’d recommend that the fiscal authorities raise their inflation target from 2% to 4%. Oddly, I’ve never seen a fiscal proponent make that recommendation. Why not? My hunch is that deep down they know that fiscal authorities can’t really control inflation. But in that case, how can they control aggregate demand?

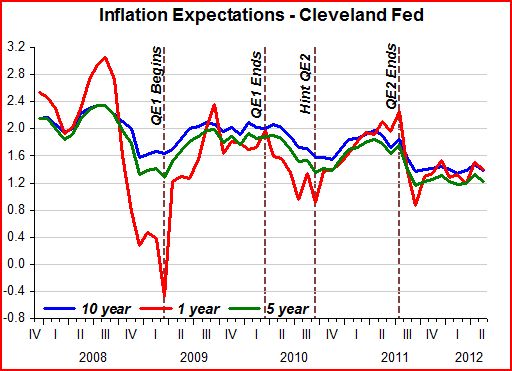

BTW, Marcus Nunes has constructed an excellent graph that shows why I’m skeptical of fiscal stimulus:

It sure looks like the Fed is trying to steer the economy.

Tags:

16. May 2012 at 04:57

Scott, know one questions that the Fed can raise inflation rates whenever it wants to.

The question is whether they should (policy) and ought (morally).

And since Monetary policy is not a social good, the moral thing is out the window. If people are hungry let Congress provide for them. If people are without jobs, let the Congress relax regulations, drop the minimum wage, etc.

THAT IS JOB OF CONGRESS.

After all, you admit freely, that my Guaranteed Income plan would solve for unemployment.

The question of the Fed doing what it “should” do, well that is the eye of the beholder.

What we know is twofold:

1. they should keep the price level stable.

2. the shouldn’t let Congress get away without doing its job.

These are both TRUTHS.

What you haven’t proven is that you aren’t so annoyed with Congress that you simply don’t expect them to act, and have given up.

It isn’t apparent because you don’t spend ANY TIME letting people see what happens under NGDPLT in th elong run.

ALSO, DeKrugman made perfectly clear he only like NGDPLT because of the promise of inflation right away.

He said it out loud, what more do you want???

16. May 2012 at 05:19

“I’d recommend that the fiscal authorities raise their inflation target from 2% to 4%. Oddly, I’ve never seen a fiscal proponent make that recommendation. Why not? My hunch is that deep down they know that fiscal authorities can’t really control inflation.”

.

Oddly enough, I think that fiscal policy has this power (to control inflation). They can do it via influencing money velocity and they have very powerful tools to do it: they may threat by confiscation unless private market accelerates money velocity and inflation.

.

Of course, it would be “interesting” too see such titanic struggle if fiscal authority declares something like “We want to see 4% inflation otherwise we will start spending money on our own” while Central Bank simultaneously targeting 2% inflation. Somebody in the comments described this clash as “immovable object, please meet unstoppable force”. But in the end I would bet my money on fiscal policy as they have something that CB lacks – army and police force – to defend its threats.

.

So it is the clash between future path of money supply (monetary policy) and future path of taxes, and thus real purchasing power of future dollar earned (fiscal policy).

16. May 2012 at 05:45

J.V., in the UK, the Treasury has direct control over the inflation target, they can raise it to 4% on a whim, no army required, just a quick letter to the Bank of England.

Great post Scott. I find the hand-wringing about investment spending in the UK particularly ironic. Slashing the investment budget by £10bn in the 2011/12 fiscal year was Labour’s plan which the Coalition have stuck to pretty closely. Now, the attack dogs say “of course that was a stupid plan, what did you expect would happen?”.

16. May 2012 at 05:47

Count Jeffrey Frankel in the NGDP Targeting camp!

http://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2012/05/16/jeffrey-frankel-favors-ngdp-targeting/

16. May 2012 at 06:34

I am a fiscal proponent and I made a 4% inflation target as part of my fiscal spending rule.

http://monetaryrealism.com/the-tc-rule-for-fiscal-policy-screams-lower-taxes-and-more-spending/

So perhaps you mean well known fiscal proponents instead of “obscure but not for long” fiscal proponents. David Beckworth made a similar proposal at our site just last month.

16. May 2012 at 06:46

Morgan:

What we know is twofold:

1. they should keep the price level stable.

2. the shouldn’t let Congress get away without doing its job.

These are both TRUTHS.

1. is not a truth. 1. is a falsehood. Stabilizing prices in a market where prices would have otherwise fallen, or risen, brings about signal distortions as to the true level of saving and consumption, i.e. the true supply of capital.

An inflationary policy of stabilizing prices throughout the 1920s led to the crash at the end of the decade.

16. May 2012 at 06:59

Sorry this is off topic, but a question has been burning in my mind. It’s very simple and straight-forward so I hope being off topic won’t be too much of a problem.

This blog often says that interest is the price of credit. If somebody on here slips and says interest is the price of money, that person is quickly jumped upon.

Certainly interest is the price of credit. So here’s my question: is it not also the price of money, depending on the context?

Take present-value-of-money calculations for example. If you want to discount money to its present value, you simply remove the interest that it will earn in the future. It seems in this case the interest is simply the difference between the price of money now and in the future. No?

Thanks.

16. May 2012 at 07:04

“there isn’t much austerity in Britain””in 2011 their budget deficit was nearly the largest in the world”

Still that’s correlation at best causation is not established. A budget deficit doesn’t prove there’s been austerity. Austerity is self-reinfocing by lowering tax reevenues as Greece is learning.

16. May 2012 at 07:05

I mean a budget deficit doesn’t prove there hassn’t been austerity.

16. May 2012 at 07:09

Major Freedom the 20s weren’t inflationary. We actually had deflation through much of the decade. From 1926 to 1933 we had deflation every year.

So whatever caused the Depression wasn’t inflation.

16. May 2012 at 07:19

Mike Sax,

I think MF was referring to the fact it took a decent amount of created inflation to keep prices stable at all. Left to their own, prices would have fallen more.

16. May 2012 at 07:23

marcus nunes:

You know, unlike the 1980s, we have all sorts of historical records available on the internet, in real time, concerning the newest monetarist religion, NGDP targeting.

The juiciest thing about all this is that we can see the names of all those who supported NGDP targeting, and the names of those who didn’t.

Inflation targeting (IT) died in 2008? OK, fine, let’s assume the zombified corpse of IT was finally laid to rest in 2008. Why did it fail? Remember, the supporters of IT thought that IT would not suffer from the flaws of stable price targeting, and was hence the end game of monetary policy. This is it, they thought, we’ve finally found the holy grail. They thought IT was the end game of monetary policy because they, like you, did not comprehend the seed of destruction inherent in what they were advocating.

The seed of destruction in NGDP targeting is even more dangerous than inflation rate targeting. And why not? If the problems of inflation get worse and worse over time, is it not expected that we will see worse and worse rescue-like ideas from its supporters? Kind of like a group of ignorant and destructive doctors with a dying patient recommending more and more extreme procedures as time goes on because they refuse to give up their destructive ways, which only hastens the patient’s death.

NGDP targeting is even more dangerous than inflation targeting because it requires even more money printing. It’s like a drug addict believing that his dying body can be healed once and for all if only he increased his dosage, on the basis that his withdrawal symptoms are getting worse and worse, and so he believes the problem is not enough drugs when the problem is too much drugs.

The only reason NGDP targeting is (slowly) gaining support is because it serves as a justification for more inflation today, which is a panacea to so many drug addicts around the country.

Just you wait what happens should NGDPLT be adopted. Then, just like now with IT, there will be calls for even more inflation, there will be calls that NGDPLT fails, that NGDPLT is too stingy a policy, that it is a scorched Earth policy that ignores the plight of suffering workers, it will allow any amount of idle resources to pile up, etc, etc, etc, etc.

IT was an increase in monetary inflation relative to original lender of last resort. NGDPLT is an increase in monetary inflation relative to IT. Once the economy becomes “addicted” to NGDPLT, the effects of 5% NGDP will wear off, and there will be calls for 6%, then 7%, because “5% was too low, and there are many unemployed people and many idle resources laying around, so we can afford to print more.”

Then the economy will implode, and yet NGDPLT remains in force, and then, just like now, the Fed chief will be accused of sleeping behind the wheel, and then, just like now, inflationists will call for another more intensive inflation policy, if the monetary system even survives that is.

In fact, NGDPLT has the potential of bringing the economy into a very long depression, much like central economic planning experiment in the USSR was an 80 year depression because capitalism was not allowed to take place.

While you are all congratulating yourselves for believing you have finally reached the holy grail of monetary policy, little do you know that it is just an accelerated move towards economic destruction.

16. May 2012 at 07:23

” My hunch is that deep down they know that fiscal authorities can’t really control inflation. But in that case, how can they control aggregate demand?”

Maddening. Fiscal spending feeds directly into Y, or so the theory goes. Perhaps they can’t control aggregate demand. How does that matter. Ultimately, what’s relevant is Y. not P.

16. May 2012 at 07:25

Mike Sax:

Major Freedom the 20s weren’t inflationary. We actually had deflation through much of the decade. From 1926 to 1933 we had deflation every year.

So whatever caused the Depression wasn’t inflation.

When Austrians say the 1920s was inflationary, they don’t mean prices, they mean aggregate money supply. So the 1920s was in fact inflationary.

You don’t have to use the same definition of inflation, but you have to at least understand the definitions being used that you are responding to.

16. May 2012 at 07:26

Mike Sankowski:

I think MF was referring to the fact it took a decent amount of created inflation to keep prices stable at all. Left to their own, prices would have fallen more.

Precisely.

16. May 2012 at 07:33

Well MF I think most people interpret inflation my way. You guys have your own idiosyncratic way of defining it and that’s find but it’s up to you to make yourself clear not for me to divine it.

If that’s what you mean fine. Next you have to explain why you think it’s a better guage-the burden of proof is on you as you’re the one with the idiosyncratic method.

16. May 2012 at 07:35

Mike Sandowski so let prices collapse and there’s no Depression? If this your view?

16. May 2012 at 07:43

What is your case that fiscal stimulus will not work at the zero lower bound? The central bank keeps hinting that if the economy needs further stimulation, congress should do it. So they will probably not offset these stimulus.

16. May 2012 at 07:54

“there isn’t much austerity in Britain””in 2011 their budget deficit was nearly the largest in the world”

Ah, but how big was the budget deficit relative to where it needed to be? Never reason from the level of the budget deficit!

(Same way that the monetary base skyrocketed in late 2008, but not by enough to prevent net monetary tightening!)

16. May 2012 at 07:58

Morgan, You said;

“know one questions that the Fed can raise inflation rates whenever it wants to”

That’s funny, almost everyone I talk to questions this. They are bemused when I explain that the big drop in AD was due to tight money.

JV, You said;

“Of course, it would be “interesting” too see such titanic struggle if fiscal authority declares something like “We want to see 4% inflation otherwise we will start spending money on our own” while Central Bank simultaneously targeting 2% inflation.”

We saw it in Japan over the past 20 years—and the BOJ won.

Thanks for that info, Britmouse.

Marcus, That’s good to hear.

Mike, See my response to JV.

Austin, Yes, but I’m using the term ‘price’ in the conventional sense, as we’d describe the price of apples. Prices are generally viewed as relative concepts, the cost in terms of other goods foregone. Obviously one could describe the price of renting apples for a few years, or renting a car, but most people would regard the purchase price as the actual price. In addition, while an increase in the supply of money will reduce the price of money, in terms of other goods, it’s not at all clear it will reduce the interest rate (as we saw in the 1970s.)

Mike Sax, Of course everyone defines austerity differently, I’m just saying that I don’t see much evidence of it in the UK, as I’d view the budget deficit as a reasonable metric. Lots of other countries are also in recession, and they had smaller deficits than Britain in 2011.

And don’t waste time with MF, he’s horribly confused about the 1920s. The monetary base did not increase significantly during the 1920s, and fell significantly in per capita terms. He’s talking about private sector increases in credit, and then blaming the Fed somehow.

Ritwik, So fiscal policy feeds directly into real GDP w/o affecting AD? Maybe so, but that’s not the Keynesian model I was talking about in this post.

16. May 2012 at 08:04

Jaap, Maybe so, but they also keep hinting that they’d like to keep inflation at 2%, which means they would offset it. The honest answer is that we simply don’t know. But if Keynesians truly believe, it’s time to start talking about fiscal authorities setting inflation targets. Instead people like Krugman seem to (implicitly) be talking about monetary authorities targeting inflation.

Integral, But there is a key difference. Fiscal stimulus is like adding fuel to the fire, to get a ship to go faster. Monetary policy is like setting the steering wheel at the proper setting–no one setting is more costly than another. Hence it makes sense to talk about the “effort” in terms of deficit spending, but not in terms of adjusting monetary policy (which is costless.)

16. May 2012 at 08:08

Scott

‘Without affecting AD’ is imprecise, meaningless. It’s a term like ‘holding monetary policy constant’. It enters Y with indeterminate or variable effects on P. It ‘affects’ AD, of course. At least that’s my understanding of the model.

Plus, why do do use AD/ inflation interchangeably? Fiscal policy can increase AD is a very different claim from ‘fiscal policy can can hit an inflation target’. The former is Keynesianism of various sorts. The latter is one corollary of the fiscal theory of the price level.

16. May 2012 at 08:10

Scott Sumner,

I’m not sure that either those who have generally been arguing against fiscal stimulus or those who have generally been arguing for fiscal stimulus are working these things out in any serious macroeconomic models. That’s part of the problem: “confidence” fairies convince some people that you can have fiscal austerity without monetary stimulus and “fiscal policy affects Y and monetary policy affects P” thinking convinces other that fiscal stimulus is necessary to maintain growth.

If there are implicit models behind the thinking of most deficit hawks and doves in the UK, I’d only want to see them as a morbidly interesting example of muddled thinking.

16. May 2012 at 08:15

Mike Sax:

Well MF I think most people interpret inflation my way. You guys have your own idiosyncratic way of defining it and that’s find but it’s up to you to make yourself clear not for me to divine it.

In every major textbook Austrians are very clear in how they define inflation.

Yes, “most people” do define inflation your way, but you don’t see me presuming that by inflation Sumner means money supply just because that’s how I define it. I know he means prices because I read what he says.

Next you have to explain why you think it’s a better guage-the burden of proof is on you as you’re the one with the idiosyncratic method.

The burden of proof is on those who adhere to “idiosyncratic” ideas? Oh hell no. The burden of proof is on anyone who makes any positive argument whatever. You are shielded from defending your arguments just because they happen to be popular. By that logic, the burden of proof during the 18th century was on the slaves, not the slave masters.

To answer your question, the reason why I define inflation as increase in the money supply (technically an increase in money supply beyond the rate of precious metals discovery, but no matter), is because A. It’s the original definition of inflation, B. It provides a clear answer for WHY prices in general rise over time, and C. It’s a friggin definition, and one is free to use any definition one wants.

ssumner:

And don’t waste time with MF, he’s horribly confused about the 1920s. The monetary base did not increase significantly during the 1920s, and fell significantly in per capita terms. He’s talking about private sector increases in credit, and then blaming the Fed somehow.

Mike Sax, Sumner is the one incredibly confused about the 1920s, indeed about the entire monetary system.

The amount of credit expanded by the banks during the 1920s was only possible because the Fed was there to backstop the banks. The monetary base doesn’t have to actually increase very much before the institution that is the Fed is ultimately responsible for the ability of fractional reserve banks to expand credit.

The Austrian theory doesn’t blame central banks per se, it blames credit expansion and inflation.

Sumner is only telling you not to “waste time” with me because he doesn’t want anyone to adopt my ideas and be yet another thorn in his NGDP side. He’s just scared, that’s all.

16. May 2012 at 08:34

Ritwik,

You seem to be using the highly confusing model of “real AD”. To get an understanding of where Scott is coming from, read these posts: http://marketmonetarist.com/2011/12/23/how-i-would-like-teach-econ-101/

http://marketmonetarist.com/2012/01/18/there-is-no-such-thing-as-fiscal-policy/

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2012/01/a-very-simple-derivation-of-the-balanced-budget-multiplier-in-a-very-monetarist-model.html

Fiscal policy attempts to stimulate the economy by increasing spending on goods – net spending, that is. We call that a shift of the AD curve, the spending being split between prices and output depending on AS.

So when you say that spending “feeds directly into Y”, you are ignoring that stimulus increases Y by increasing MV. It shifts demand curves to the right. Whether that leads to more quantities demanded or higher prices depends on supply curves. Either way, enough nominal spending can always raise prices. So if stimulus can raise the total amount of spending, then it can control the price level. So fiscal policy controls inflation (if the Fed holds the money supply constant). And that is not the fiscal theory of the price level, that’s the monetarist interpretation of AD.

16. May 2012 at 08:41

Scott,

no one says the Fed can’t raise inflation…

they say it SHOULDN’T.

Period the end.

Ask yourself how many of the bemused were bemused when Perry said Ben would get tarred and feathered in TX.

Deep down, people don’t want inflation. Period. The end.

You can point to the suffering ZMP workers, and you can promise more wealth for the already thriving…

But until you SAY how your plan = less inflation in the long run, you are not putting the meat in the window.

Decision makers don’t like inflation….

So Scott’s pitch is:

Long term MUCH less inflation, Mid term less inflation, short term, and tad more, just a smidge really.

You can tell that story. It is a true story.

Why don’t you tell it?

16. May 2012 at 08:47

Jeffrey Frankel writes an obituary for inflation targeting and considers what might replace it.

16. May 2012 at 08:48

“Deep down, people don’t want inflation. Period. The end”

Well I want inflation but then I guess I’m not the people you have in mind. I don’t care about long term low inflation either. I’d rather send the millions back to work and let you worry about inflation.

Again Morgan you are close to your 4.5 target with no catch up. Isn’t it obvious the status quo isn’t working?

16. May 2012 at 09:02

Deep down, people don’t want inflation. Period. The end.

First of all, i am pretty skeptical that with 8.2% unemployment QE would produce it (might affect commodities but that’s less than 15% of PCE).

Second, I strongly disagree and as i’ve pointed out numerous times, its not clear to me that inflation hurts mortgage debt holders more than it actually helps them.

Mortgage equity withdraw is about 240 Bn per year right now on a stock of ~10 Tn, which means that mortgages are already depreciating 2.2%/yr.

By reducing cyclical unemployment and reducing the real spread between mortgage debt and collateral value, the propensity to default declines and value of debt is actually increased {for some small values, clearly this would not be true of a 10% inflation policy}.

Beckworth posted a good empirical paper on Adolfatto’s blog about the impact of leaving the gold standard and higher inflation on corporate debt values during the depression: despite the higher inflation, corporate debt prices went up because of reduced propensity to default.

http://faculty.chicagobooth.edu/finance/papers/repudiation11.pdf

16. May 2012 at 09:08

Saturos

I’ve read the AD/AS model, Scott’s posts and the posts that you are referring to. I don’t agree and I don’t find AD/AS to be a particularly useful model, except for keeping in mind some of the more useful things that Scott says – e.g. don’t reason from a price chang.

Scott/ the AD/AS version of market monetarism speaks/writes at such high levels of abstraction that it is impossible to make meaningful statements about what the implications are. If you ask ‘how can the central bank always hit an NGDP target’, he responds with ‘I don’t know of a single example where the central bank tried to inflate and failed’. Take a step back and see why people are talking about raising inflation expectations. The logic is Wicksellian/Keynesian – you are trying to equilibrate the real rate of interest to the current ‘natural rate of interest’. This is supposed to stimulate spending (real) and employment. Or equivalently, you could directly spend and employ people (fiscal policy). Whether that raises inflation expectations or increases the natural rate of interest, we don’t know. (I am supposing for this argument that fiscal policy ‘works’ – it may not) But it gets spending (real) back on track and employs people.

Scott is asking supporters of fiscal policy to offer a solution/explanation within the current regime of people expecting the central bank to target inflation. It’s a false question. It’s made worse by his constant confounding of ‘influence’ with ‘control’. It’s made even worse by this : “My hunch is that deep down they know that fiscal authorities can’t really control inflation. But in that case, how can they control aggregate demand?”. What is that even supposed to mean? Can you explain it in terms of the rectangular nominal AD hyperbola?

16. May 2012 at 09:11

Saturos/ Scott

Let’s go one step at a time. Explain why you think being able to ‘control’ inflation is a pre-requisite to being able to ‘control’ aggregate demand. As a corollary, define what ‘control’ means.

16. May 2012 at 09:27

Ritwik, you said,

“The logic is Wicksellian/Keynesian – you are trying to equilibrate the real rate of interest to the current ‘natural rate of interest’.”

Not necessarily.

http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2011/08/is-this-a-liquidity-trap.html

“Or equivalently, you could directly spend and employ people (fiscal policy). “

Even under the generous assumption that the spending targets unemployed resources, haven’t you paid any attention to Scott’s recent string of posts (indeed, the graph above) showing how when spending exceeds the level that the Fed is comfortable with, they tighten? Look, fiscal stimulus spends more on some goods and workers, but in a classical economy that necessarily means less spending elsewhere. And when the Fed holds NGDP constant (or puts a ceiling on inflation as spending begins to push up prices), that is effectively a classical economy.

“Can you explain it in terms of the rectangular nominal AD hyperbola?”

Indeed I can, that’s exactly how you should read that quote.

(Controlling AD) => (controlling inflation). Hence, the contrapositive says that (not Controlling inflation) => (controlling AD). Inflation is produced by the rectangular hyperbola AD shifting to the right ahead of the AS curve, with a higher intersection on the P axis, and a still higher one next period, etc. If Fiscal policy can’t boost V, then it can’t shift the AD curve to the right. Hence, it can’t raise inflation. Equivalently, if it can’t raise inflation, it can’t boost V and AD. (Fiscal policy can also work when it is a money-financed deficit, or “helicopter drop”, but that’s really monetary policy in disguise.)

Indeed I don’t even understand what “spending (real)” is supposed to mean – spending is a flow of money. If the total volume of these flows is held constant (AD curve fixed) then there is complete crowding out of spending flows, one replacing another. The Ad curve shifts forward only if the central bank increases the money supply or if Fiscal policy reduces money demand one way or another. That’s it.

Are you sure you read (and understood) all the posts I linked to? They’re pretty clear.

16. May 2012 at 09:27

Control = “determine the level of”. I would say ceteris paribus, Scott wouldn’t.

16. May 2012 at 09:31

Good post as usual, Scott, but I would disagree on one point:

“Either way, fiscal stimulus is ineffective in the UK, as it’s offset by the BOE doing less unconventional monetary stimulus”

This statement hinges crucially on the question of whether unconventional monetary stimulus actually works, and this is what I think modern theory has to say on this:

Case 1: Unconventional monetary stimulus doesn’t work. In this case fiscal stimulus is effective at the zero lower bound because whether the central bank removes QE is of no consequence. This is my view (and probably Krugman’s). This is true in most modern macro models with nominal rigidities (NK etc) when the central bank has no commitment and an inflation target. QE can’t work if agents expect the printed money to be destroyed next year to curb future inflation.

Case 2: Unconventional monetary stimulus works. In this case there is NEVER a good case for fiscal stimulus in the class of models above, even at the ZLB, as you can always use unconventional monetary policy instead. This is true if you think the central bank can commit to future actions, especially allowing future inflation above target, and hence isn’t expected to destroy printed QE money too quickly.

Hence my take is that theory has strong predictions on the success of QE, and a lot of it is to do with central bank commitment. Ultimately this becomes an empirical question: if there is evidence that QE works we shouldn’t use fiscal stimulus, and if there is evidence it doesn’t then we should use fiscal stimulus. Not sure what the empirics currently say.

Finally, the above model doesn’t take into account financial frictions and the fact that TARP style programs could work by swapping illiquid for liquid assets. In this case I’m not sure whether fiscal stimulus would be necessary.

Thanks for the post.

16. May 2012 at 09:31

“The AD curve shifts forward only if the central bank increases the money supply or if Fiscal policy reduces money demand one way or another.”

Or, of course, money demand can also fall if expectations of future NGDP growth rise (due to fiscal or monetary policy), or due to exogenous shocks. Sorry, I got a little huffy there.

16. May 2012 at 09:33

“Hence, the contrapositive says that (not Controlling inflation) => (controlling AD).”

Whoops, I meant (not controlling inflation) => (not controlling AD). Gotta slow down.

16. May 2012 at 10:03

Saturos

1. You/Scott are inferring too much from that graph. What does Scott’s above graph show? That 1 yr inflation expectations rise with QE? Sorry, but big friggin deal!! Of course they do. The expectatons themselves have however dropped from 2.1%-2.5% to 1.2%-1.4%. And you infer that the ‘Fed steers the economy’? Actually, Scott writes ‘trying to steer the economy’, which is a wee bit different from ‘controls AD’, no? Further, Marcus Nunes presents that graph as the failure of Fed policy. Scott/ you however see it as a sign of central bank omnipotence. You assume omnipotence and conclude omnipotence.

2. Nick’s liquidity trap post posits an upward sloping IS curve. Bill Woolsey, market monetarist, disagrees. Rsj, whose comments on that post I agree with, disagrees. Nick uses his framework because he does not want to have -ve natural rate. There’s no reason to assume that framework. That post is an interesting one, esp. for its multiple equilibria but Nick makes it clear that he is not even aiming to handle why or how higher inflation expectations may escape the liquidity trap. I don’t know why you believe that linking it here proves or furthers your argument.

3. I understand your contrapositive. Thanks. However, my question wasn’t as literal as that. I understand ‘control’ as hitting a pre-specified target. I understand ‘influence’ as being able to shift a little bit here and there, without exerting full control on where it’s going to be. Indeed, that’s the sense I get from your definition of control as well. The opposite of control, thus, is not ‘does not influence at all’. You are proving to me that if fiscal policy can’t shift the AD curve, it can’t control inflation. Sure (techincally, it still can if it can shift/change the shape of the AS curve under a predtermined AD shifting regime, but let’s leave that out for the moment as we are talking about the demand side). But ‘does not control’ is not the same as ‘does not influence at all’.

Let me then rephrase the Keynesian fiscal policy argument. MP can shift the AD curve out when there’s no liquidity trap. FP can shift the AD curve out in all states of the world, but also has unintended effects on the AS curve, causing the inflation/price level to be unstable. MP does not affect AS, so is preferred during normal times. FP is the only option during liquidity trap. There, that’s the Keynesian argument in AD/AS rectangular hyperbola lingo. It’s not particularly illuminating, because the foundations of this argument are from a different model. But it can be adjusted to suit your framework.

16. May 2012 at 10:10

Saturos

When I said ‘feeds’ directly into Y, I was also being imprecise with my language. What I should have said is, it feeds into Y by increasing PY, but how much del(PY) will be needed to hit a certain level of del(Y) is not known. It increases PY until the required level of del Y is hit. So fiscal policy influences AD, of course, but it’s not controlling AD or inflation expectations in any meaningful sense.

16. May 2012 at 10:13

Scott:

Correct me if I’m wrong, but wouldn’t fiscal stimulus be effective if it has a higher RGDP to inflation ratio than monetary policy? For example, lets say that a fiscal stimulus pops RGDP 2% and inflation 1%, the Fed then withdraws monetary stimulus until inflation returns to its original level but this only cuts RGDP by 1%. Your then ahead through using fiscal stimulus even with an inflation hawk central bank.

16. May 2012 at 10:28

Greenlaw is also confused about the 1969-1970 recession, which was monetary in nature: The Fed cut base growth from a peak of 8.6% in 1968 to about 4% in 1969. As a consequence, NGDP growth was also cut in half by mid 1969 before slowing to 3.3% A.R. in Q4 69.

Where fiscal policy shows up, as you say, is on the supply-side: despite the very sharp slowdown in NGDP, the GDP price deflator (domestic inflation) averaged just over 5% from late 1969 through 1970.

It would take a decade from that point before policy makers began to fully appreciate the interaction of high inflation with high marginal tax rates, thanks to Laffer and his curve. Unfortunately, this seems to be a lesson the profession — led by saez, piketty and diamond, armed with mathematical models built on the quicksand of unsound assumptions and leap-of-faith reasoning — is trying very hard to forget.

16. May 2012 at 10:39

Ritwik, I won’t go into the liquidity trap here, see Scott’s numerous posts on the subject (try the FAQs). Monetary injections expected to be permanent boost spending today, and if you target the forecast then you can also target specific levels of MV, “nominal AD”, or as we say here NGDP (all the same thing).

What we want is for monetary policy to hit specific levels of NGDP, to move the AD curve up to a specific position each year. Of course we don’t fully control the split between prices and output (btw supply shocks are generally 1-off jumps in prices, not sustained inflation), but of course if we get AD back to a level that is consistent with rigid wage and debt contracts, then eveentually AS shifts back to its natural position and we get lower prices and more employment.

Just as monetary policy can adjust the base until the market expects the desired level of NGDP or spending growth, it can also adjust to produce the desired level of inflation (that’s what central banks currently do). Similarly, holding M constant, fiscal policy could in principle (within limits) adjust until markets expected the desired level of spending/NGDP growth.

But you’re right, we don’t control AS and can’t target the desired level of Y (or “real demand) directly. Instead we target the desired level of nominal spending, the level high enough to buy up all the output at a feasible price level. The split between prices and output is determined by AS. Or we could target inflation, but of course Y is what we want. For a given increase in spending, we want less P and more Y. So we target the level of spending which is enough to buy all the Y at the natural AS level. We want to return to the original path of spending. If Y is still too low then it must be due to supply constraints which MP can’t do anything about, or fiscal stimulus for that matter (fiscal reform, or “supply-side stimulus” a different matter).

In sum, anything fiscal policy can do monetary policy does better. This is true with central bank crowding out and also true otherwise (temporary fiscal stimulus suffers the same problem as temporary monetary injections. But injections that are expected to be permanent boost spending.)

16. May 2012 at 10:44

“Similarly, holding M constant, fiscal policy could in principle (within limits) adjust until markets expected the desired level of spending/NGDP growth.”

And by the same token, fiscal policy can in principle target inflation as well. It would be highly inefficient, but a modest inflation target might be hit. Of course it would have to be permanent, so if Ricardian Equivalence holds then money demand is affected through the tax on nominal income (balanced budget multiplier. Or if it’s monetized deficits then that’s really MP).

16. May 2012 at 11:03

I would assume that DeLong probably belongs in Krugman’s camp too, no?

16. May 2012 at 11:10

Saturos

I’m not saying I agree with the liquidity trap. I’m saying that’s the Keynesian argument. Scott’s challenge to the Keynesians is a false one – if you were to refer to the Keynesian argument in an AD/AS framework, you would say that yes, fiscal policy can ‘control’ (I abhor using that word – no one ‘controls’ any macroeconomic aggregate, really)inflation. Indeed, you say as much.

About FP vs MP, I don’t really have a view, except to say that targeted fiscal spending (like building roads/ bridges) has AS effects of its own. You can call it supply side stimulus/ reform/ whatever. I prefer to think about government spending in the framework of network externalities and public choice, bypassing macroeconomic stabilisation altogether.

About your classification of what is fiscal policy and what is monetary, I don’t agree, but I don’t really care. I’ll just say that in your framework, since all monetizations are monetary policy, all real activity is monetary policy as everything must be eventually monetized. Ok, that’s a bit of overstatement, but you would say, for example, that India’s problems with inflation in the 70s and the 80s were due to bad ‘monetary policy’. Fine. It’s not particularly illuminating though. Looking at government spending, however, is.

16. May 2012 at 11:13

Scott,

I think it would help Sax a lot if you could explain why EVEN WITH no catch up / make up inflation, starting with NGDPLT today would be a big improvement by at least Mid-Term.

I say this is what happens:

1. the chance of further f’ups by the Fed ends.

2. this puts animus on public sector make govt. more efficient, the Fed rewards us with cheaper money.

3. this is a positive feedback loop – “hey! automating the govt, reducing minimum wage, ending Davis-Bacon, drilling in Mike’s back yard, this stuff keeps our rates low!”

4. economy improves faster than it would under current expectations.

Scott, you can just say “Yup” now.

—

Sax, the question is #2, how long do you stumble around yelling that we shouldn’t REALLY TRY to make govt. more efficient, cut regs, etc?

16. May 2012 at 11:15

India’s problems in the 70’s and 80’s were due to Indira Gandhi, period. I’m sorry she died that way, but I can’t say I miss her.

16. May 2012 at 13:15

In other words Morgan what you’re saying is basically this. If right now-for argument sake-NGDOP already is 4.5% and yet we still aren’t happy with output and GDP then the answer is to pass Paul Ryan’s budget first and then later mabyer there’ll be monetary stimulus.

I get what you’re saying-very clever. Am I signing the dotted line on this-no way. You’re saying Ryan’s budget now and maybe QE later.

16. May 2012 at 13:26

Scott,

here are the juicy bits about the British austerity from today’s BoE press conference:

“Faisal Islam, Channel 4 News: Governor, in the past you’ve welcomed the impact of the depreciation of sterling on the rebalancing of the British economy to make a more sustainable economy. At what point do you get worried about the rise of sterling?

Mervyn King: Well, I don’t think Central Bank Governors can ever expect the exchange rate to move exactly as they would wish. And I think the developments in recent weeks have not been entirely unexpected, given what’s happening in the euro area. We have to accept that and feed it into our judgement as to what we should do for our own policy.

But there is no doubt that the big depreciation, 25% – that’s still intact broadly speaking – is a vital part of the rebalancing; it’s an absolutely essential part. And that’s why I’ve always said that the approach to policy that is very important, and which I think very few people I know dissent from, is a mixture of a loose monetary policy, with low interest rates, asset purchases and a large depreciation of sterling; and on the other hand a gradual tightening of fiscal policy to get back to a much lower structural deficit over the medium term. And that broad balance of policy is the right approach, and it’s the one which we are pursuing and few other countries in the world have actually got round to doing yet.”

“Jennifer Ryan, Bloomberg News: This is to follow on a little bit from the remark you just made about the balance between monetary and fiscal policy. I just would wonder if you could comment a bit on, you know whether – at a time when you’ve lowered your growth projections, when your central projection for inflation is to be perhaps below the target in two years’ time, there’s been a decision not to add stimulus into the economy when the government is looking like it’s going to continue with the tightest fiscal squeeze. I mean I would have thought at this point the government might well be disappointed that there’s not been a decision to add more stimulus. And you know are you also of a mind that perhaps there might be scope to loosen the austerity measures in order to promote more growth and you know – sort of following on from what’s going on in Europe?

Mervyn King: Well, our task is monetary policy. We set interest rates and the programme of asset purchases. And as I said, looking ahead two years, our judgement last week was that the risks around the target were evenly balanced. So I think it was a perfectly reasonable decision to do no more.

I think you need to bear in mind that the asset purchases we’ve made between October and last month will continue to stimulate the economy for some time to come. The fact that we’re not continuing the programme at this stage doesn’t mean to say that that the effect doesn’t continue to pass through the economy; it does. And the option is always open to resume the programme. I mean, we haven’t made any decisions, of stop it and do no more. This is a decision we can review every single month. But we have our task, which is to look at the balance of risk to inflation. That’s what we’ve done and that’s how we made our decision. ”

The best part was when FT has asked this question:

“Chris Giles, Financial Times: Just staying on the monetary fiscal mix, could you tell us what assumed multiplier the MPC is using, given the particular form of fiscal tightening we’re getting over the forecast horizon? You can tell us either it as a Keynesian multiplier or define what the headwind taking off growth in percentage points of GDP or either would do?

Can you tell us what discussions the MPC have had about whether you want to change that assumption in this forecasting round? …. What would make you change your view on that particular point, on what the fiscal multiplier is and how that affects monetary policy?”

The verbal non-answer to this question is much less interesting than facial expressions of Charlie Bean who responded to all that. You should definitely take a look at the webcast here ( at 40:30 ):

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/inflationreport/ir1202.aspx

16. May 2012 at 13:26

Scott,

here are the juicy bits about the British austerity from today’s BoE press conference:

“Faisal Islam, Channel 4 News: Governor, in the past you’ve welcomed the impact of the depreciation of sterling on the rebalancing of the British economy to make a more sustainable economy. At what point do you get worried about the rise of sterling?

Mervyn King: Well, I don’t think Central Bank Governors can ever expect the exchange rate to move exactly as they would wish. And I think the developments in recent weeks have not been entirely unexpected, given what’s happening in the euro area. We have to accept that and feed it into our judgement as to what we should do for our own policy.

But there is no doubt that the big depreciation, 25% – that’s still intact broadly speaking – is a vital part of the rebalancing; it’s an absolutely essential part. And that’s why I’ve always said that the approach to policy that is very important, and which I think very few people I know dissent from, is a mixture of a loose monetary policy, with low interest rates, asset purchases and a large depreciation of sterling; and on the other hand a gradual tightening of fiscal policy to get back to a much lower structural deficit over the medium term. And that broad balance of policy is the right approach, and it’s the one which we are pursuing and few other countries in the world have actually got round to doing yet.”

“Jennifer Ryan, Bloomberg News: This is to follow on a little bit from the remark you just made about the balance between monetary and fiscal policy. I just would wonder if you could comment a bit on, you know whether – at a time when you’ve lowered your growth projections, when your central projection for inflation is to be perhaps below the target in two years’ time, there’s been a decision not to add stimulus into the economy when the government is looking like it’s going to continue with the tightest fiscal squeeze. I mean I would have thought at this point the government might well be disappointed that there’s not been a decision to add more stimulus. And you know are you also of a mind that perhaps there might be scope to loosen the austerity measures in order to promote more growth and you know – sort of following on from what’s going on in Europe?

Mervyn King: Well, our task is monetary policy. We set interest rates and the programme of asset purchases. And as I said, looking ahead two years, our judgement last week was that the risks around the target were evenly balanced. So I think it was a perfectly reasonable decision to do no more.

I think you need to bear in mind that the asset purchases we’ve made between October and last month will continue to stimulate the economy for some time to come. The fact that we’re not continuing the programme at this stage doesn’t mean to say that that the effect doesn’t continue to pass through the economy; it does. And the option is always open to resume the programme. I mean, we haven’t made any decisions, of stop it and do no more. This is a decision we can review every single month. But we have our task, which is to look at the balance of risk to inflation. That’s what we’ve done and that’s how we made our decision. ”

The best part was when FT has asked this question:

“Chris Giles, Financial Times: Just staying on the monetary fiscal mix, could you tell us what assumed multiplier the MPC is using, given the particular form of fiscal tightening we’re getting over the forecast horizon? You can tell us either it as a Keynesian multiplier or define what the headwind taking off growth in percentage points of GDP or either would do?

Can you tell us what discussions the MPC have had about whether you want to change that assumption in this forecasting round? …. What would make you change your view on that particular point, on what the fiscal multiplier is and how that affects monetary policy?”

The verbal non-answer to this question is much less interesting than facial expressions of Charlie Bean who responded to all that. You should definitely take a look at the webcast here ( at 40:30 ):

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Pages/inflationreport/ir1202.aspx

16. May 2012 at 14:12

123, I couldn’t get the Bank’s webcast working at all today, what was Bean’s facial expression?

16. May 2012 at 14:33

Sax, that’s not what I’m saying…

1. NGDPLT starts today. No make up.

2. Next month we’re down on RGDP, guess what? You get Inflation.

3. Great Inflation works!

4. RGDP is higher now, so is inflation! Time to raise rates!

5. Shit! Let’s cut the least productive senior public employees! Keep rate low, hurrah!

6. Hey that works! Let’s Drill Baby, Drill!

—-

Does this help you understand? It’s isn’t Paul Ryan first.

It’s a very clear constant headbumping on 4.5%, that gives us a positive feedback loop.

You shouldn’t fret, this will likely only run until we really have only good low hanging fruit regulations, and a public employee class as productive as the private sector.

16. May 2012 at 15:23

It’s amazing that the discussion about inflation here is almost as insanely obsessed with the notion as the Fed. Why is this when there is an indication of a rather large output gap nearly everywhere we look?

Shouldn’t we only be concerned with overloading the economy with demand when we start getting close to that point when inflationary pressures start to pick up, when the gap narrows considerably? Of course no one likes inflation, though it isn’t that much of worry until we have more demand than ability to produce; but it also seems that they like this miserable state of affairs much less, with record numbers of people receiving public assistance and employment market dysfunction. Democrats talk all day long about equality and social mobility, but this atmosphere of lack of opportunity isn’t buying them that at all, and they can’t buy it by robbing the rich because it will just displace others, until there is no productivity left. That is a reality of the monetary straightjacket. And Republicans talk all day about the enormous cost of safety net programs, spending and debt, and this current state just compounds all of things that upset them because of the lack of growth. How many people would say they are happier and feel more secure today than they were 8 years ago, or even 5 years ago? Not many, I would guess. I know I would not say that.

Sheer terror of the inflation bogeyman, way beyond the point of being rational, has done some really terrible things to this country, and I certainly hope we come to our senses before it gets the better of us and our society just comes unglued.

16. May 2012 at 15:49

“Shouldn’t we only be concerned with overloading the economy with demand when we start getting close to that point when inflationary pressures start to pick up, when the gap narrows considerably?”

The answer to that Bonnie is of course. But the conversation gets highjacked by Austrians

16. May 2012 at 16:05

Fiscal spending is effective in creating monetary stimulus to the degree that people believe the Fed – when push comes to shove – would not let the federal govt. go bankrupt.

However, given the recent events in the world, I don’t think anyone takes anything for certain.

16. May 2012 at 16:32

Stiglitz is in favor of more government spending but not “fiscal stimulus”. He wants more spending to address “structural unemployment” from the liberal side of policy (plus perceived structural problems in finance industry and energy policy). He also wants government spending to reduce inequality (basically, redistribution). I may be mis-characterizing his views, but I think he believes reducing inequality will improve the economy even if no net money was spent.

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/to-cure-the-economy

Another way, it is possible Tyler Cowen would be in favor of money spent to reduce regulation, but he wouldn’t call it “fiscal stimulus” even though it is technically a fiscal policy to stimulate the economy …

16. May 2012 at 17:33

Sax, I thought we were so close to a breakthrough!

16. May 2012 at 17:39

“Another way, it is possible Tyler Cowen would be in favor of money spent to reduce regulation.”

This is fantasy land. It doesn’t exist.

16. May 2012 at 18:53

LOL-what’s the matter now I ripped on Austrians? C’mon Morgan no way I join Team Austrians.

16. May 2012 at 19:11

Bonnie:

Shouldn’t we only be concerned with overloading the economy with demand when we start getting close to that point when inflationary pressures start to pick up, when the gap narrows considerably?

It’s amazing to behold how you are completely and utterly ignoring WHY there is a “gap”, meaning idle resources, in the first place. Could it be, oh I don’t know, prior inflation that misdirected resources? Oh no, that can’t happen, that’s impossible! Inflation is never a problem when it doesn’t lead to rising price indexes.

Mike Sax:

The answer to that Bonnie is of course. But the conversation gets highjacked by Austrians

Funny how you interpret Austrians as hijackers, and market monetarists as hijackees, rather than no hijackers or hijackees.

The answer is of course not. The reason there is a huge gap in the first place is because resources were allocated in lines where they are not sustainable. Inflation cannot possibly be the solution when it is the cause of the problem.

Of course, these ideas barely get out because they are so often hijacked by inflationists who don’t understand how the market works and only ever seek to treat the symptoms rather than the causes.

16. May 2012 at 20:24

Sax, I taught you WHY it isn’t Paul Ryan first.

That’s a big deal.

You need to reach deep and explore if it is OK with you if we really have only good low hanging fruit regulations, and a public employee class ARE FIRCED to be as productive as the private sector.

You get over that, and you can LOVE NGDPLT too.

It should be enuff for you Sax.

Own it.

Extra points for a real response.

16. May 2012 at 20:27

Britmouse,

Mr. Bean couldn’t have done it better than Charlie did.

Internet Explorer + Windows Media Player or Firefox + Flash shall be used for BoE webcasts. Chrome and Safari do not work.

17. May 2012 at 03:12

I think Krugman is assuming that the Fed has actied/will act as if it can do little once the zero bound is reached. So far that assumption has proven right. Note Bernanke’s statement regarding the Fed’s inability to offset the fiscal shock of the simultaneous shock of the expiration of the Bush tax cuts, the payroll tax cut, and the sequester. One hopes he’s just playing chicken with Congress, but what if he is actually anoubcing a policy of doing nothing?

17. May 2012 at 03:13

I think Krugman is assuming that the Fed has acted/will act as if it can do little once the zero bound is reached. So far that assumption has proven right. Note Bernanke’s statement regarding the Fed’s inability to offset the fiscal shock of the simultaneous shock of the expiration of the Bush tax cuts, the payroll tax cut, and the sequester. One hopes he’s just playing chicken with Congress, but what if he is actually anoubcing a policy of doing nothing?

17. May 2012 at 04:30

Worries about inflation are like worries about the ladder being broken, when the ladder has only been kicked down and needs to be set back up, so that we can reach the fruit higher up in the tree.

17. May 2012 at 05:18

Now see Morgan I give real responses but I can’t pretend to buy stuff I don’t buy.

I know you think Scott should go about things differently. But if you’re tyring to turn a Keynesian like me his method if anything is better.

When I hear you explain it what I get is that NGDP is just a backdoor way of imposing austerity. That’s as real as I get.

17. May 2012 at 05:25

Again don’t get me wrong I have no problem with NGDP in theory. If it were somehow up to me what the Fed does tomorrow I might even say go for it-it sounds better than inlfation targeting, whichi I basically hate.

For me inflation targeting means-“we just want low inflation for its own sake to prove we can or to help bondholders and creditors or just because we like it and who cares about the unemployed.”

NGDP in theory at least at first sounds better-the Fed won’t have the fetish for inflation.

But though I apprecaite your honesty Morgan it also kind of confirms some of my worst suspcions.

Now I’m being real with you in that I’m telling you how I honsetly see it.

17. May 2012 at 05:35

Becky:

Worries about inflation are like worries about the ladder being broken, when the ladder has only been kicked down and needs to be set back up, so that we can reach the fruit higher up in the tree.

Worries about deflation are like worries about the notch marks on yardsticks being too narrow, when the yardstick has only been warped and bent and needs to be left alone to market forces, so that we can correctly measure relative values.

Back to the ladder, inflation pushes the lowest rungs down even further as the lowest rungs contain people whose incomes don’t rise as fast as prices. It also pushes the entire ladder down as inflation systematically DISTORTS economic calculation, preventing investors and consumers from coordinating their behaviors in a sustainable way.

17. May 2012 at 06:22

Thomas Hutcheson –

“One hopes he’s just playing chicken with Congress, but what if he is actually announcing a policy of doing nothing?”

I think he’s playing chicken. He’ll soon have a full board, and hopefully that will help.

http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2012/05/15/senate-democrats-to-bring-fed-nominees-to-floor-for-votes/

My vote for the best case scenario:

1. The lame duck session is hopelessly gridlocked, every budget deal is filibustered. The “fiscal cliff” comes, cutting the budget deficit by some $700 Billion (static analysis). The impasse goes on throughout 2013.

2. The Treasury shifts completely to short term T-Bills for financing, so the Fed has more to buy.

3. The Fed uses the budget stalemate as cover to shift course to NGDP targeting, 10% the first year, 5% per year, thereafter.

The extra GDP goes to 7% real and 3% PCE inflation. Revenues for 2013 come in $200 Billion above static projections, lower outlays for poverty programs save another $100 Billion. The total deficit for 2013 is $1 Trillion lower than 2012.

The success leads several deficit hawk Senators to form a coalition to oppose any attempts to reverse the fiscal cliff. A new Federal Reserve Act is proposed enshrining NGDP targeting into law, and removing bank appointees from the Regional Fed Banks – Bernanke testifies in support. A Balanced Budget Amendment passes both Houses with the necessary 2/3 vote, after Paul Krugman’s historic testimony sways many Democrats. “Now that NGDP targeting has proven that fiscal stimulus is superfluous, obviously those of us who believe in government should support balancing the budget each year.”

In related news, the Nobel Prize in Economics is awarded to …

17. May 2012 at 07:57

Ritwik, I don’t use ADS/inflation interchangeably. I claim a policy that boosts AD is ipso facto a policy that boosts inflation. Do you disagree?

W, Peden. Good point.

Morgan, They do say the Fed can’t raise inflation.

Thanks Jim Glass, I’m doing a post.

Ritwik, Regarding your second post, there is nothing mysterious about my transmission mechanism. It relies on the expected future hot potato effect and it calls for pegging the price of NGDP futures, to get around the problem of policy lags. It’s certainly possible to peg the price of NGDP futures.

The Keynesian interest rate mechanism plays no role in my analysis.

errr, I agree that those are the issues, but I’ve never seen a shred of evidence that monetary policy doesn’t work at the zero bound, and I’ve seen lots of evidence that it does.

I’d add that the major central banks certainly think they could do more, they just don’t want to.

Jfield, In theory, yes, but in practice the opposite is likely to be true, as private spending is usually (not always) more efficient than public spending.

Tommy Dorsett, I completely agree.

Adam, That’s usually true.

123, He’s right about the need for tight fiscal/easy money—now do it!!

Couldn’t get the webcast to run–I’ll try again later.

Bonnie, Good point.

Statsguy, Yes, but that would take way more fiscal stimulus than is plausible–look at Japan, even they don’t have inflation.

Jason, Good point.

Thomas, Yes, I’ve often given Krugman credit for being right about the Fed’s passivity at the zero bound.

17. May 2012 at 08:52

Scott, webcast works only with the newest versions of Internet Explorer + Windows Media Player or Firefox + Flash.

26. February 2017 at 05:54

[…] http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=14355#comments […]