Evan Soltas provides the best argument for NGDP targeting

When Evan Soltas first asked me to add his blog to my blogroll, I politely declined. I thought it was cute that a high school senior was attempting blogging, but come on, let’s be serious.

Big mistake. Unfortunately, his blog is so consistently good that it can no longer be ignored. A few days ago Evan provided six arguments in favor of NGDP targeting. Nick Rowe pointed out that the sixth (which Evan thought up himself) was a sort of refutation of Schumpeterian economics. Evan follows up with a post that quotes from an appalling piece in the Boston Globe:

Today, few mainstream economists share Schumpeter’s belief in the unerring regularity of business cycles. And some point out that there’s plenty of room for creative destruction when the economy is strong – witness the turmoil over the past few years in the music industry, or the airlines, or, for that matter, the newspaper industry.

Economists do agree, however, that recessions help to right economies that have lost touch with reality. Recessions not only cull unhealthy companies, they expose financial gimmickry. They punish groundless optimism and the rampant speculation it feeds – in fanciful Internet ventures in the 1990s, for example, or in housing over the past few years.

Economists do agree?!?!?!? God I hope it’s not so. Evan criticizes the Globe article and then cites Robert Lucas’s 1972 paper that looked at business cycles as a signal extraction problem. Evan concludes the post with this gem:

If you don’t believe the idea that firms in pool A have imperfect information, try it yourself. Here’s a simple case: the level of employment and the number of firms in the manufacturing industry have been in secular contraction in the United States for decades. However, since 2008, there has been unusual employment growth in manufacturing. To what extent does this reflect cyclical conditions, given that the 2008 recession was very deep and eliminated a large fraction of manufacturing jobs in the United States? To what extent, conversely, does it represent a secular recovery in that industry? The fact that any answer would contain a significant amount of uncertainty means that firms in the first pool face a signal extraction problem under conditions of imperfect information.

By this logic, which embraces as did Schumpeter the central importance of creative destruction, recessions do not assist the process. In fact, by corrupting the signal by which firms decide to enter or exit industries, recessions make the creative destruction process slower, less efficient, and more costly.

When I was his age . . . well I’d rather not even think about how far behind I was. I got a C in freshman English at Wisconsin, and I can’t even imagine how badly written my blog posts would have been back then. For some odd reason Evan reminds me of a younger Mankiw, or a younger Mishkin. I took a class from Mishkin in the 1970s, and also briefly met Mankiw many years ago. Both seemed like young men on the fast track to great success—possessing that mysterious intangible that I never seemed able to find. When I was young I had some personal “issues” (I believe the clinical term is “complete loser.”)

But enough about me, I’d like to now explain the title of this post. No, the best argument is not the 6 points listed by Evan, although they provide an excellent argument for NGDP targeting. Instead, the best argument is that Evans Soltas is attracted to the idea. Unlike all us older economists who come to the table with all sorts of ideological and methodological baggage, Evan is able to look out over the macro landscape like a diner examining a beautiful buffet table. And what sort of framework seems most appealing to the best and the brightest of generation Z? NGDP targeting! I’d make the same claim about Matt Yglesias, another extremely bright blogger who approached this issue as an outsider (he’s got a philosophy background.) The NGDP approach provides an intuitively appealing framework for what’s gone wrong since 2008, and what needs to be done to fix it.

Recently I had dinner with a co-author of one of the popular intro textbooks. We discussed various ideas (he was interested in my market monetarist approach.) When I explain my AS/AD ideas his eyes really lit up. I argued that no intro student can possible understand the “3 reasons” why the textbook AD curve slopes downward (I forgot about Evan) and that it should be replaced with a rectangular hyperbola representing a given amount of nominal expenditure. THIS is what we mean by aggregate demand; no other definition matches our profession’s fixation on the classical dichotomy—the idea that nominal shocks affect both prices and output in the short run, but only prices in the long run. Call it the NE curve (nominal expenditure) and explain to students that macro’s mostly the study of how nominal changes get partitioned between prices and real output.

And this is also why people like Jan Hatzius, Brad DeLong, Christy Romer and to a lesser extent Paul Krugman are all drawn to NGDP targeting. Once you start thinking in NGDP terms, it’s hard to go back. It’s just so damn intuitive.

So the fact that Evan Soltas, likely winner of the 2030 John Bates Clark award, is drawn to NGDP targeting is an incredibly positive sign, and dare I say not just for the policy itself, but also for the market monetarist group that championed the policy when almost no one was paying attention to the collapse in NGDP.

Part 2. Did base growth help during the Great Depression?

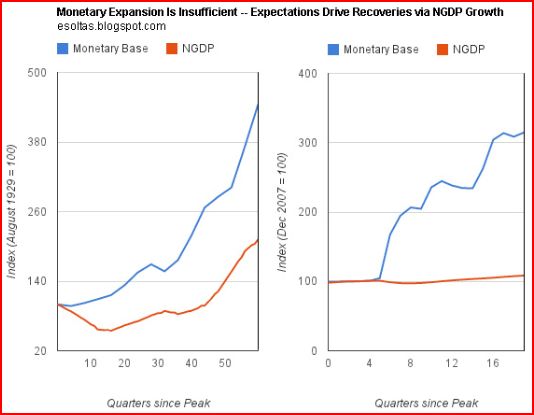

Since I’ve heaped so much praise on Evan, it’s time to mildly criticize one of his recent blog posts. In this post Evan provided some graphs:

And then added these comments:

The first graph shows that even the most massive amounts of monetary expansion are ineffective medicine for NGDP expansion. What matters is expectations; growth in the medium run is conditional on expectations — not on the monetary base or price level.

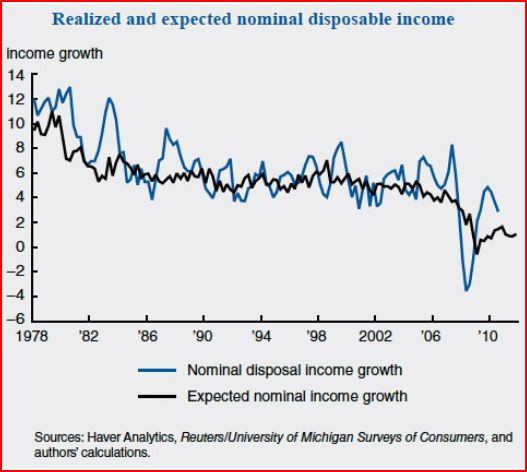

The second graph shows the extent to which monetary policy seems to have forgotten this. Nominal income growth expectations have been right at zero since the recession, when before that they had been stable at the 5 percent level for decades. The findings come from this study by the Chicago FRB, which I found through this Chicago Magazine article. Paging Scott Sumner…

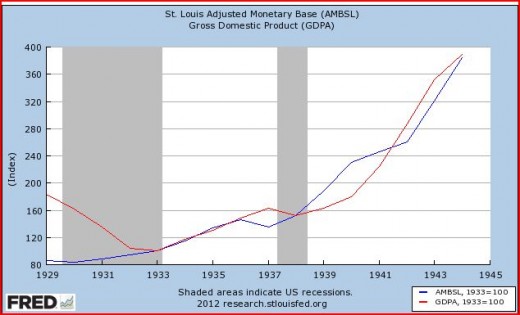

I mostly agree, and very much like the second graph, but I’d like to slightly quibble with the first graph. I redrew it setting both the base and NGDP equal to 100 in 1933, not 1929:

Notice that the base rose in the early 1930s while NGDP fell sharply. That’s because base demand was engorged by two factors, banking distress and ultra-low interest rates. The ultra-low interest rates continued between 1933 and 1944, but banking distress fell sharply after dollar devaluation and the creation of FDIC. Thus after 1933 the base and NGDP rose at roughly similar rates, both nearly quadrupling over those 11 years. As you know, I don’t regard the base as a reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy, because base demand can be highly volatile under certain conditions. But the supply of base money is still very important; indeed it’s the major factor driving NGDP over the long term.

Of course things get even more complicated when you add interest on reserves, and when base injections are viewed as temporary. So I certainly endorse Evan’s argument that it’s NGDP expectations that we should focus on, not the monetary base. But we shouldn’t forget that those NGDP expectations are themselves driven by beliefs about expected long run path of the monetary base (and perhaps IOR.)

Tags:

15. May 2012 at 08:49

FWIW, I was always intuitively attracted to the notion of AD as simply nominal spending and a QTM approach to spending, recessions and monetary policy, and found Keynesianism itself as well as vestigial Keynesian thinking to be “mind-numbingly illogical” (to borrow your memorable phrase) and came to this blog because I at last found someone who though like I did (only much, much better…)

Also, I see Evan’s signal extraction argument (it was Nick who put him on to the Lucas paper, btw) as being just another version of the standard argument for price stability – not only, as you say, to prevent output volatility, but also because price level volatility introduced too much noise into the price system in general (What does it mean for me if the price of apples doubles tommorow?). And that’s the real reason why we don’t like high inflation – because high inflation tends to be unstable inflation, which means an unpredictable price level.

15. May 2012 at 08:50

I tried to leave a comment for him on his blog, but I don’t have a Blogger account, and my Name/URL posts were getting swallowed.

15. May 2012 at 09:06

If I were Evan, I would include this post in my PhD admissions application.

15. May 2012 at 09:07

Congrats to Evan Soltas!

And what a wonder is this thing we call the Internet–tearing asunder the formalities and institutions and the opaque reality that kept good ideas buried.

Side note to Scott Sumner. We are born in the same year, and you do not qualify as a “loser,” in the past or now. Crickey, you became a prof and now write the most important blog going.

Onward Market Monetarists! Next stop: The Fed.

15. May 2012 at 09:19

As a naif, let me offer a couple observations.

1) NGDP targeting appeals to me because it sounds like a free lunch. In the current situation, we print some money, use that money to retire government debt or acquire assets for public use, some underpants gnomes get involved somehow, and then we have an economic recovery! What’s not to like?

2) NGDP targeting scares me for the same reason — it sounds too good to be true. Like all government schemes, I suspect I’m missing the part where it goes terribly wrong, the dinosaurs get out of their cages, and next thing you know, a T-Rex is running around L.A. for some reason.

3) On the other hand, I say give it a try. I like it better than fiscal stimulus or doing nothing, which seem to be the alternatives. At this point I’d p on a spark plug if I thought it would help.

15. May 2012 at 09:24

“Call it the NE curve (nominal expenditure) and explain to students that macro’s mostly the study of how nominal changes get partitioned between prices and real output.”

The NERO model: Nominal Expenditures/Real Output. I like it.

“Onward Market Monetarists! Next stop: The Fed.”

When I read that, Ben, I had a sudden vision of this:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rzcLQRXW6B0

and then perhaps this

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GJoM7V54T-c

15. May 2012 at 09:27

J Mann, no, the money increases NGDP via the excess cash balance mechanism. Actually the money supply doesn’t need to go up at all – a credible threat would reduce money demand to the same effect.

The only way it can go wrong is if the target isn’t credible, or if the target is missed, which is pretty unlikely if you’re targeting the forecast.

15. May 2012 at 09:28

Is it possible that the correlation between NGDP and base money was primarily based on the Fed’s need to supply sufficient reserves to meet expanding private debt levels when excess reserves were minimal? If so, the huge supply of excess reserves now in the system and IOR policy may alter that relationship.

15. May 2012 at 09:30

After you’ve read Scott’s FAQS, here’s a good intro: http://www.moneyweek.com/news-and-charts/economics/uk/eocnomic-growth-market-monetarism-ngdp-20200

15. May 2012 at 10:21

Scott, you’re not going to tell us which co-author it was, are you ;D

15. May 2012 at 10:36

Sautoros, thanks. Ok, from a non math, non model guy, let me add:

0) Best case scenario, the credible threat to print money in slowdowns and soak it up in booms means that there is no need to actually do it. Second best case scenario, if the threat lacks credibility or if stage 0 fails for some unforeseen reason, then go to #1.

15. May 2012 at 10:41

The Federal Reserve has primarily focused on targeting the price of reserves (interest rates), letting the quantity float by always providing a sufficient amount. The amount of base money should correlate reasonably well with the increasing demand for credit under these conditions. Steve Keen has shown in his models of the economy that changes in debt directly impact aggregate demand and thereby NGDP. One should therefore expect to see a positive correlation between NGDP and base money while those circumstances persist.

Paying IOR above the risk-free-rate has resulted in a surge of excess reserves and base money uncorrelated with any increase in the demand for credit. Changing Fed policy has altered the conditions under which the previous relationship existed. The supply of base money (which was correlated but didn’t drive NGDP) may therefore no longer even show any material correlation with NGDP (as long as current condition prevail).

http://bubblesandbusts.blogspot.com/2012/05/ngdp-targeting-changing-policy-changes_15.html

15. May 2012 at 11:17

its interesting how well anchored nominal expectations are from about 86-2006.

15. May 2012 at 11:18

Woj, you are confusing the demand for money with the demand for credit. They are completely different things.

J Mann, you may want to look at these posts:

http://marketmonetarist.com/2011/10/31/the-inverse-relationship-between-central-banks-credibility-and-credibility-of-monetarism/

http://marketmonetarist.com/2012/03/18/how-unstable-is-velocity/

http://marketmonetarist.com/2012/03/06/long-and-variable-leads-and-lags/

http://macromarketmusings.blogspot.com.au/2011/06/how-effective-is-monetary-policy.html

My main problem with your (1) is your “underpants gnome” visualization. Yes, I love South Park too, but that’s not how you should be seeing it at all. A better metaphor would be Chuck Norris: http://worthwhile.typepad.com/worthwhile_canadian_initi/2011/10/monetary-policy-as-a-threat-strategy.html

Let Chuck Norris roundhouse kick the question mark out of the flowchart in your head.

15. May 2012 at 11:30

“Economists do agree?!?!?!? God I hope it’s not so.”

It is depressing, but I would guess if you present that paragraph to a sampling of what passes for professional macroeconomists today, at least 30% would agree. Probably more.

Krugman likes to compare Austerians to leech doctors. And really what has happened the past four years, reminds of a disease epidemic spreading throughout the country. Laymen and politicians don’t really know how to attack the problem. So, they gather all of the top doctors together and ask them for their advice. The advice they come up with is mass leeching.

The more I read, the more Krugman’s “We are in the Dark Age of macroeconomics” rings true. These people may as well be saying that we all sacrifice our first born to help the economy. This is how stupid their suggestions sound.

15. May 2012 at 11:36

Sorry, if that last post sounded angry. I see we are entering another “OMG, we are all going to die!” moment in the markets and our excuse for policy makers are twiddling their thumbs. Not only that, they think twiddling thumbs is the appropriate policy response.

15. May 2012 at 11:48

LOL, I went on msn.com moments after making this post and this is what was on my front page:

http://health.msn.com/healthy-living/medieval-medical-treatments

Man these search engines are good now.

15. May 2012 at 11:51

Ugh, Soltas is well on his way to not comprehending economic calculation, nor the signal distortions that inflation, even expected inflation, brings about, nor the actual causes of recessions.

Bernanke went to Princeton, and he has been completely clueless his entire Fed tenure. Looks like Princeton has a standing policy of attracting the economically illiterate.

15. May 2012 at 11:55

Saturos,

This from Ann Pettifor, http://bit.ly/Khb7sY:

“The fact is, and it has been so since 1694, when a borrower approaches a bank for a loan, the funds for the loan are not in the bank. They are created when, after assessing risk, a bank clerk enters the loan amount into a ledger, demands collateral; sets the rate of interest on the loan and after agreement has been reached, transfers the funds – as ‘bank money’ – from the bank’s account to the borrower’s account. This loan creates a deposit in the borrower’s account. Loans create deposits. Credit creates money.

It gets better: credit creates economic activity.”

15. May 2012 at 12:04

Woj:

Pettifor writes: “It gets better: credit creates economic activity.”

It creates lending activity yes, but it doesn’t create wealth. It just redistributes it from person to person in ways that would have been different had there been only lending backed by prior real saving.

It is truly remarkable how prevalent the myth of credit expansion creating new wealth really is.

15. May 2012 at 12:21

Soltas censors his blog. He doesn’t permit any views counter to his own.

15. May 2012 at 13:00

Scott,

A million thoughts; hopefully you have time to responds.

1) I wonder how Evan Soltas will fare at Princeton as a student-blogger who opposes the inflation targeting doctrine of his professors?

2) I agree with point 6. I’ve been looking for the exact data, but I find it believe that, since 2008:

* Housing demolition/disrepair has equaled or exceeded housing construction

* Corporate depreciation has exceeded corporate capex (this never happened before between 1945 and 2008)

* Government spending excluding transfer payments has fallen

* Labor force participation has dropped precipitously

Every component of the economy engaged in real activity is self-liquidating due to the instability. At least bond holders have done well!

3) It’s actually quite common for people in peripherally related fields to solve problems that vex the incumbent experts. Like chemists solving biochemistry problems, or physicists solving math problems.

15. May 2012 at 14:27

Evan is the reason I started blogging, even though I’m not nearly as skilled as he is at writing. I also find the NGDP targeting framework very convincing, and I hope that the same is true for other young aspiring economists and that market monetarism can have its day in the sun with my generation.

15. May 2012 at 15:19

“But the supply of base money is still very important; indeed it’s the major factor driving NGDP over the long term.”

Why? Isn’t it true that any supply of base money (including zero!) is consistent with any NGDP? That is, you don’t need base money to transact. You don’t need it to be a payment system. You just need it to be a reference unit.

15. May 2012 at 16:18

“…well I’d rather not even think about how far behind I was.”

Many is the time I wish I’d had enough sense to study economics when I was young, when it was far easier to learn. Still, think how different the ‘lay of the land’ actually is now. Evan sees things we scarcely could have imagined in the seventies. NGDPLT is intuitive now, because this is the right time for it to happen.

15. May 2012 at 17:05

Saturos, Thanks, I agree about Lucas. Indeed that was the model we were taught at Chicago in the 1970s.

I’m unable to leave comments at many blogs–don’t know why.

John Hall, He’s already accepted at Princeton.

Ben, I made $1500 my first year after leaving Chicago. Even in 1981 that income didn’t go far.

J Mann, You said;

“Like all government schemes”

You are completely missing the point–but don’t feel bad as 99% of other people do as well. This recession is the “government scheme.” I’m proposing that we end the government scheme, that we stop jerking NGDP around wildly, and have a stable monetary policy.

But I’m glad you are willing to give it a try.

Saturos, I like the NERO acronym.

Woj, You said;

“Is it possible that the correlation between NGDP and base money was primarily based on the Fed’s need to supply sufficient reserves to meet expanding private debt levels when excess reserves were minimal? If so, the huge supply of excess reserves now in the system and IOR policy may alter that relationship.”

Actually it was quite different. The Fed responded passively to a huge inflow of gold and the revaluation of gold, by increasing the base, and there were fairly high levels of ERs. Causality went from the base to NGDP, not the other way around.

Saturos, The author might not mind, but it was a private conversation . . . so I ought to check first.

He reads my blog, so maybe he’ll leave a comment.

Woj, It’s the base, not debt that drives NGDP in normal times (when rates are positive). When rates are near zero, and/or IOR is paid, the base is still important, but the linkages are more complicated–expectations are key.

dwb, Interesting.

Liberal Roman, I fear your 30% estimate is right.

Woj, If I could give you one piece of advice, it would be to never, ever read the MMTers. They think they have the mysterious key to banking, that somehow all us conventional economists have missed, even though their observations are simplistic and irrelevant to monetary economics. There’s no there there.

MF, If he blacklists your comments, then I’d add that he has better judgment than I do.

Steve, He’ll do very well there–I’d guess he’ll be a star student. They won’t have a problem with him arguing for NGDP targeting, it’s a respected idea that’s been talked about by lots of mainstream economists–including Mankiw.

I agree with your other points. Let me know if I didn’t respond to a specific query you had.

Lulu, Thanks, that’s music to my ears.

Max, Economics isn’t about what you need, it’s about what you want. People find cash convenient, and hence it has value.

Becky, Actually I was quite good at economics, it was the rest of my life that was a mess.

15. May 2012 at 19:58

Estimates by the Department of Commerce put the net debt figure as of the end of 1939 at $183.2 billion compared with a figure of $190.9 billion as of the end of 1929. I.e., for the period encompassing the Great Depression there was no over all debt expansion.

During the Great-Depression the economy moved forward to the extent that commercial bank credit expanded:

Change in…………………. Bank

Total Debt………………… Debt

1916 ,,,,, ,,,,,

1917 ,,,,, 12.3 ,,,,, 4.4

1918 ,,,,, 23 ,,,,, 4.7

1919 ,,,,, 10.6 ,,,,, 5.2

1920 ,,,,, 7.4 ,,,,, 4.6

1921 ,,,,, 0.4 ,,,,, -3.8

1922 ,,,,, 4.2 ,,,,, -0.5

1923 ,,,,, 6.3 ,,,,, 3.3

1924 ,,,,, 6.7 ,,,,, 2.5

1925 ,,,,, 9.6 ,,,,, 3.4

1926 ,,,,, 6.2 ,,,,, 0.8

1927 ,,,,, 8.5 ,,,,, 3.2

1928 ,,,,, 8.6 ,,,,, 2.7

1929 ,,,,, 5 ,,,,, -0.1

1930 ,,,,, 0.1 ,,,,, -2.9

1931 ,,,,, -9.1 ,,,,, -6.6

1932 ,,,,, -7.3 ,,,,, -4.3

1933 ,,,,, -6.1 ,,,,, -3.7

1934 ,,,,, 2.9 ,,,,, 2.7

1935 ,,,,, 3.3 ,,,,, 2.3

1936 ,,,,, 5.6 ,,,,, 3.5

1937 ,,,,, 1.7 ,,,,, -1.1

1938 ,,,,, -2.4 ,,,,, 0.3

1939 ,,,,, 3.6 ,,,,, 2

1940 ,,,,, 6.7 ,,,,, 2.9

1941 ,,,,, 21.7 ,,,,, 6.9

1942 ,,,,, 47.4 ,,,,, 20.6

1943 ,,,,, 54.6 ,,,,, 23.1

1944 ,,,,, 57.2 ,,,,, 28.5

1945 ,,,,, 35.6 ,,,,, 23.9

1946 ,,,,, -8.9 ,,,,, -11

1947 ,,,,, 10.5 ,,,,, 1.4

1948 ,,,,, 16.3 ,,,,, -1.1

1949 ,,,,, 13.6 ,,,,, 1.3

1950 ,,,,, 40.3 ,,,,, 9.2

1951 ,,,,, 33 ,,,,, 7.5

1952 ,,,,, 31.5 ,,,,, 10.1

1953 ,,,,, 32 ,,,,, 5.1

1954 ,,,,, 20.8 ,,,,, 10.4

15. May 2012 at 20:16

As its mandate Fed should choose NGDP targeting since that is what it can realistically be capable of doing. Directly controlling unemployment levels may require resurrecting Stalin or Mao.

15. May 2012 at 22:21

ssumner:

MF, If he blacklists your comments, then I’d add that he has better judgment than I do.

Is that supposed to be funny, or insulting? Come on, you can do better.

There was nothing in my comments on his blog that deserved censoring. I merely linked to this chart:

http://i.imgur.com/AOHwQ.png

And said that the differences in declines of productive stages cannot be explained by a decline in aggregate demand, as per his comment that recessions are caused by declines in aggregate demand.

That did not deserve censoring, and the fact that he did censor it is proof that he doesn’t want even the slightest inkling of countervailing comments.

PS Your judgment is better than his.

15. May 2012 at 23:49

“PS Your judgment is better than his.”

Awwww, Scott, you know what this means? Deep deep down, MF really likes you!

16. May 2012 at 03:32

Btw, Scott, what do you think of Tyler’s latest?

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2012/05/i-know-i-know-m2-isnt-exactly-the-right-indicator.html

16. May 2012 at 05:47

Saturos, Scott – thanks for your comments.

It’s vanity, I know, but I offer myself up as a generic reasonably educated person who doesn’t understand the math. I can’t tell whether it’s rational ignorance, irrational ignorance, or stupidity, but I’m not going to try to understand macro at the math level. So here’s my reasoning:

1) Since I don’t understand it, I first review the claims of authorities. Lots of economists seem unconvinced or at least skeptical, and some of them seem to have a reasonable understanding of macro. But (and here’s where the appeal to authority gets epistemological interesting), Scott claims that the leading lights agree with him on all key premises, and nobody seems to disagree much.

2) I’m certainly convinced that the Fed could credibly threaten to create inflation if it wanted to, and could create inflation if it wanted to. I suppose the counterargument is that any money the Fed created would be hoarded, resulting in no inflation now and destructive hyperinflation when the dam finally breaks, but presumably we can watch for that.

3) The political problem is that the policy of “the Fed has to credibly threaten 3-5% inflation if the economy doesn’t take off” doubtless sounds frightening to people who are still fighting the last war, and therefore afraid of inflation. I guess for those people, the key things to sell them is that (a) there are structures in place that will prevent the government from using this as a blank check to create even *more* inflation; and (b) this is controllable – it stops at worst at 5%, and hopefully not even there.

3.1) (Yes, I get that the best case scenario is that the inflation isn’t necessary, but you can’t credibly commit to inflation if necessary unless you are prepared to bite the bullet.)

4) As I said, the biggest sticking point for me is that it sounds too good to be true. Scott – do you have a FAQ or a paper on what could go wrong and how to monitor/address/prevent those risks?

5) Scott – point taken that we currently have a scheme, but using the term non-pejoratively, creating a futures market in order to enact a son-of-Taylor rule in an effort to manage market expectations on a government currency is also a scheme. Particularly once it got put in place by real-world humans (politicians, even!), my gut tells me that the process wouldn’t function exactly as envisioned.

16. May 2012 at 06:29

Saturos:

Awwww, Scott, you know what this means? Deep deep down, MF really likes you!

Actually Saturos, that comment was honestly about my conceit. I consider those who censor my posts to have worse judgment than those who don’t censor my posts.

If you want to call that a “liking”, then so be it, just be advised that it has nothing to do with his ideas. After all, Soltas has almost identical ideas as Sumner, so to me they’re equally wrong.

16. May 2012 at 07:07

J Mann said:

3) The political problem is that the policy of “the Fed has to credibly threaten 3-5% inflation if the economy doesn’t take off” doubtless sounds frightening to people who are still fighting the last war, and therefore afraid of inflation. I guess for those people, the key things to sell them is that (a) there are structures in place that will prevent the government from using this as a blank check to create even *more* inflation; and (b) this is controllable – it stops at worst at 5%, and hopefully not even there.

…

I consider myself a bit educated when it comes to Macro-economics and I basically agree with him. Indeed, I see this as a massive weakness in the proponent of “we need inflation to spur consumption/AD”.

1- When inflation rises and people are afraid, they might save even MORE, to get real savings despite the inflation gnawing at their bank account.

2- Who said we know how to put the genie back in the bottle? Inflation has a history of getting out of hand.

3- If inflation is supposed to work its magic by slowly (or not so slowly) destroying debt, what about trying some staged debt forgiveness program? One that would minimise the moral hazard consequences. I can think of ways of doing that and I bet it’d be pretty good bang-for-the-buck as far as government spending is concerned.

4- NGDP targeting is already something we are doing indirectly with a 2% inflation target and a 2 to 3% real GDP growth. I have no real objection to fusing both and announcing a single number but the whole point is that no one is interested in -1% real output and +4% inflation.

5- Thus, in conclusion, if you want to convince slo-mo like me and/or the average Fed President, you need to explain very clearly how a +4-5% inflation threat (let alone its actuality) transforms a -1 to 0% real growth number into a +2 to 3%.

16. May 2012 at 07:11

… meant to add to my post above…

… because, at the end of the day, only one – at most two – economic variables matter. The Main One is employment and a subsequent one is the dispersion (variance) around the median GDP per capita number.

16. May 2012 at 08:17

From the about section on his blog, I was under the impression he was going to Princeton for undergrad…so I referenced grad school.

16. May 2012 at 08:18

Rustem, I agree.

MF, Not my business.

Saturos, Good post, but I don’t find M2 reliable. Still, you wonder why people keep saying the ECB has an easy money policy. What metric are they looking at?

J Mann, I meant that we had a reasonably good monetary policy from 1984 to 2007, and then sharply deviated from that policy in 2008. I say we should have stuck with the old policy, or at least go back to it. How is that more risky than our current disastrous course?

I have a paper in National Affairs that you can google, which explain my views. If you are going to spend a lot of time thinking about inflation, you first need to think about why it’s bad.

Frederic, You said;

“I consider myself a bit educated when it comes to Macro-economics and I basically agree with him. Indeed, I see this as a massive weakness in the proponent of “we need inflation to spur consumption/AD”.”

I also oppose attempts to spur consumption, so we agree there.

I’m puzzled by your comment that we already have a 5% NGDP target–check out my reply to J Mann. We had that until 2008, and then dropped it.

16. May 2012 at 08:18

John, OK.

16. May 2012 at 08:25

I don’t get this.

In a world with significant rising productivity — greater output as lower cost — why can’t we have growing GDP without a growing monetary base?

What is the advantage to real GDP of a signficantly growing monetary base.

16. May 2012 at 08:39

I still don’t understand why the AD curve shouldn’t be horizontal with an inflation targeting central bank.

16. May 2012 at 08:45

With inflation on the vertical axis, yes it is, if you put the target into the curve, as opposed to modelling it as shifts in the curve.

16. May 2012 at 08:56

J Mann,

Read this post: http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=69

Then read the post I linked to earlier (the last one) to start to get an understanding of the fact that expectations drive asset prices, and hence aggregate demand (or nominal spending – they are really the same thing.)

We aren’t trying to raise inflation, we’re trying to raise nominal spending (rightward shift of AD). We aren’t trying to do that b raising inflation expectations, we’re trying to do that by raising nominal spending expectations (aka NGDP expectations). The biggest determinant of current (AD/NGDP) is future expected AD (NGDP).

As to your last point, Scott’s scheme is far less discretionary (and prone to human error) than the current scheme. If you look at Scott’s arguments in his old posts, you’ll see that markets have been consistently right about NGDP growth, and the Fed consistently wrong. It only makes sense to put the task of stabilizing NGDP growth (which is the optimal monetary policy: http://marketmonetarist.com/2011/12/23/how-i-would-like-teach-econ-101/) into the market’s hands.

(I was looking for the post where Scott talks about expanding the FOMC to include a million members, ie the public, but couldn’t find it.)

16. May 2012 at 08:57

I meant that we had a reasonably good monetary policy from 1984 to 2007, and then sharply deviated from that policy in 2008 … a 5% NGDP target … We had that until 2008, and then dropped it.

Maybe it’s simply that Greenspan was better at the job than Bernanke.

16. May 2012 at 09:05

J Mann, and definitely read this too: http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=1164

16. May 2012 at 15:15

“NGDP expectations are themselves driven by beliefs about expected long run path of the monetary base (and perhaps IOR.)”

Required reserve balances DRIVE the economy period (see Thornton). MO is not a base. Currency has no expansion coefficient. Excess reserves are idle & unused. Of course that’s heresy in the world of monetary economics.

Also as yet undiscovered is the fact that:

“Securities purchased (and sold) by the Fed, for example, could be absorbing assets that were held by the non-bank private sector or by the banking system itself.”

http://bit.ly/KuakdE

But the Fed’s research staff missed the corollary – IOeR’s “could be absorbing assets that were held by the non-bank private sector or by the banking system itself.”

It takes increasing infusions of Reserve Bank credit (and/or Government Deficits), to generate each new, inflation-adjusted, dollar amounts, of nominal gDp. Why? Because the utilization of bank credit to finance real-investment or government deficits does not constitute a utilization of savings since financing is accomplished by the creation of new money. Contrary to Keynes, in national income accounting, S doesn’t not equal I.

How does this apply to the current recovery?

IOeRs induce dis-intermediation (where the financial intermediaries shrink in size — but the commercial banking system stays the same). In other words the Fed’s research staff does not know the difference between money & liquid assets.

It is not as Bill Gross stated (“QE1 & QE2 destroyed credit creation”), rather the Fed destroyed the credit transmitting non-banks. I.e., the CBs are credit creators & the non-banks are credit transmitters.

The non-banks are the most important lending sector in our economy (or pre-Great Recession), represented 82% of the pooling & lending markets (see: Z.1 release, sectors, e.g., MMMFs, commercial paper, GSEs, etc.).

And lending by CBs is inflationary, whereas lending by the non-banks (where savings = investment), is not inflationary – ceteris paribus.

16. May 2012 at 15:15

The key here is that stability in the growth of NGDP is the kind of stability that entrepreneurs and investors and prudent consumers are interested in, that instability in the growth of NGDP is precisely what they all fear. (Of course, each individual has also his own worries, specific to him.) The policy of targeting stable growth of NGDP would be much more popular if everyone recognized the importance of this goal, as being *the uniquely effective salve for general risk aversion*.

You might gain a lot of traction if you would simply provide convincing evidence that this, rather than stability in, say, the CPI, is *the* desideratum of the risk-averse (in general).

17. May 2012 at 01:06

Scott, in reply to my points, you said:

“I also oppose attempts to spur consumption, so we agree there”.

Sure. And that’s why I come here and read your stuff. But, to be fair, even “Austerians” would say they’re looking to spur private consumption by reducing public deficits and re-inflating “confidence” and, err, expectations…

“I’m puzzled by your comment that we already have a 5% NGDP target-check out my reply to J Mann. We had that until 2008, and then dropped it”.

We still have it but “as an ideal”. We’re just failing to hit it because the Fed and co are not convinced that cranking up inflation will lead to a re-balancing of the composition of NGDP i.e. that hitting 4-5% inflation while growth is 0-1% will then somehow trans-mutate into 3% growth and 2% inflation.

I expanded a bit on my reserve to your strategy in an article on my modest blog. http://theredbanker.blogspot.co.uk/2012/05/ngdp-targeting-i-like-it-but.html#more

I would be happy for you to tell me how wrong I am and explain why further.

17. May 2012 at 08:31

Greg, Is that aimed at me? I don’t favor targeting the base.

Jim glass, Maybe, but his public statements since the crisis began have not been impressive.

flow5, What about in economies with no banking system.

Philo, Yes, I tried to address that in my National Affairs piece.

Frederic, I don’t think you are correctly characterizing my proposal. It is not some sort if disguised call for inflation. Presenting it to people that way is very misleading. The inflation rate under my plan is no different from under inflation target, at least on average.

And it doesn’t rely on rational expectations. BTW, the reason people in the “real world” are so contemptuous of ratex is that they have no idea what it is and the role it plays in modelling. In economics it means “consistent expectations” not some sort of perfect foresight.

17. May 2012 at 16:44

Scott’s argument re: newcomers applies to me. I had never really heard of macro when the crash happened. I’d always been interested in economics but knew little about it, and my reading was spotty even for popular economics.

Before finding (or re-finding) Scott’s blog, I had pretty thoroughly absorbed the narratives on the right and the left. I had done a great deal of reading, and I’d understood what I read.

Practically the moment I realized what Scott was talking about, I was on board.

My husband (a historian at NYU) has read very little about NGDP-targeting, and he’s on board, too, just from listening to me describe it.

(He is not persuadable on the question of the crash and its cause, however.)

18. May 2012 at 18:14

Catherine, Thanks, that’s good to hear.

20. May 2012 at 09:42

Your National Affairs piece shows that NGDP targeting is preferable to inflation targeting. But a perfectionist would want to know if some other sort of targeting would be better still: What is the *ideally best* magnitude for the Fed to target? The question has an academic flavor; for practical political purposes it may be reasonable to brush perfectionism aside. But note that if you had a simple argument that NGDP was the ideally best Fed target, it would be extremely powerful””for practical-political as well as for theoretical purposes. I saw no such argument in your National Affairs piece (which, by the way, was superlatively well done; I put you in Milton Friedman’s class””i.e., the highest class””as a popular essayist on economic matters). (It occurs to me that there is some vagueness about the concept of GDP””some uncertainty about what to include””which would need clearing up before the “simple, extremely powerful” argument I am looking for could be formulated.)

21. May 2012 at 11:19

Thanks Philo. Ideally you’d want to stablize an index of nominal hourly wage rates. For various pragmatic reasons I support NGDP as a pretty good second best policy, at least for large economies.

22. May 2012 at 10:01

“[A]n index of nominal hourly wage rates”–but exactly how would that be structured? Again, this question is “academic”–when you can’t even get political support for NGDP targeting, you must be much further from getting it for NHWRI (nominal hourly wage rage index) targeting; and why confuse the issue by even mentioning the latter?

But one wants to communicate with several different audiences. There are, for example, the general public, the economics profession (broadly defined), and (a narrower band) those who are deeply interested in economic theory. It is for this last group that you might produce some narrowly academic theorizing; and getting more of these people on your side might even produce practical political results (admittedly, only in the rather distant future).

But I shall leave the decision how to apportion your focus to you.

23. May 2012 at 06:29

Philo, You said;

“”[A]n index of nominal hourly wage rates”-but exactly how would that be structured? Again, this question is “academic”-when you can’t even get political support for NGDP targeting, you must be much further from getting it for NHWRI (nominal hourly wage rage index) targeting; and why confuse the issue by even mentioning the latter?”

I think you must have misinterpreted me. I do think there are political problems with wage targeting (and also practical problems) Hence I have focused exclusively on NGDP targeting. So I don’t understand why you are critical here.

I also don’t agree that I can’t get political support for NGDP targeting. In 1985 someone might have written “but you can’t get political support for inflation targeting.” Why might someone have said such a silly thing in 1985? Perhaps because there weren’t any countries doing inflation targeting in 1985. We now know that this sort of reasoning is faulty. You can’t assume the future will be the same as the past. Support for NGDP targeting among economists is growing very fast. That’s precisely what happened before inflation targeting was adopted.

23. May 2012 at 16:31

“So I don’t understand why you are critical here.” I wasn’t criticizing you; I was doing something entirely different: making plausible remarks on your behalf. Sorry my exposition wasn’t clearer; my whole post seems to have misfired.

25. May 2012 at 12:20

Philo, Sorry, I must have misunderstood your comment–sometimes I read too quickly.

26. May 2012 at 19:45

Thanks for even trying to respond to comments; you go ‘way beyond the call of duty!

19. August 2012 at 06:53

[…] attention he’s receiving from the media and from other influential bloggers (e.g., Scott Sumner is a fan). But there is at least some evidence to suggest that Evan’s family background may have helped […]

14. September 2012 at 09:30

This whole conversation is stupid. The equation is simple, conservation of energy, you cant get something for nothing, and if humans consume more than they produce the system goes bankrupt. End of story.

16. September 2012 at 07:39

Re: John Spikes’ …”if humans consume more than they produce the system goes bankrupt”…seems to leave robots out of the equation. Given continuation of the rapid advancements in robotics one can expect a higher percentage of robot population that produces much more than it consumes. Inventors,bankers and service providers may stay busy and the rest of the community can be supported by NGDP targeting policies that provide a good quality of life for those who are happily unemployed.

3. January 2013 at 11:03

[…] Scott Sumner has labeled him the “likely winner of the 2030 John Bates Clark award” : http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=14337). Soltas also frequently contributes to Bloomberg’s The […]

18. January 2013 at 16:12

[…] Scott Sumner has labeled him the “likely winner of the 2030 John Bates Clark award” : Sumner’s praise). Soltas also frequently contributes to Bloomberg’s The […]

5. February 2013 at 16:24

[…] Scott Sumner has taught economics at Bentley University for the past 30 years. He earned a BA in economics at Wisconsin and a PhD at Chicago. His research has been in the field of monetary economics, particularly the role of the gold standard in the Great Depression. He blogs at The Money Illusion. […]

7. June 2013 at 15:25

I partially understand the attraction of NGDP. Still, it seems to me that domestic product only matters if purchasing power exists to consume that product. In other words, NGDP only looks at part of the picture, the product side or supply side. The reality of NGDP as it is being executed today, in my limited understanding, is that it transfers risk away from reward, and income growth away from common labor.

Anything that transfers income growth, or growth in purchasing power, away from common labor aka the middle class, is a very bad thing indeed. Sooner or later, there will be no demand for the product. In other words, NGDP will be sitting at the bottom of the hole it has dug with it’s shiny shovel. In short, my opinion is that Quantitative easing can not be reversed except over the very very long term (hundred years or more). The securities purchased by the USG cannot be sold back to the market without a dramatic market correction being instigated over any time frame less than ten-fold what they were purchased over.

Run your curves again, and inject the effect of sales by USG of 1 trillion dollars a year in securities for ten years.

That’s my perspective. I am not an economist, or a college professor, or a high school student. Just an average worker. Who has seen his purchasing power cut in half while NGDP has been in play via Quantitative Easing and Qualitative Easing.

My expectation is that deflation will continue to need to be prevented in some sectors, and that inflation will continue to rise at the same time in other sectors. The Fed and others can pick whichever metrics suit their purpose for the day. Only when purchasing power increases in the USA will the economy in the USA improve for the majority of voters in the USA.

Thanks,

Larry

7. June 2013 at 16:27

Larry Bradshaw,

NGDP only includes sold products, so it is not possible to have NGDP growth with NGDI (Nominal Gross Domestic Income) growth that is equal to the NGDP growth. Also-

“common labor aka the middle class”

I barely understand the British class system and I am sure that I shall never understand the American class system.