Non-monetary demand shocks are a “barbarous relic”

A recent Free Exchange article caught my eye:

And in some circumstances the drop in demand induced by a supply shock may be larger than the decline in supply—a source of deflationary, rather than inflationary, pressure.

This idea is explored in a new working paper by Veronica Guerrieri of the University of Chicago, Guido Lorenzoni of Northwestern University, Ludwig Straub of Harvard University and Iván Werning of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. If some sectors of the economy shut down entirely, affected workers will curtail their spending dramatically. Spending by other workers could make up for the shortfall—only if the goods and services that can still be produced are substitutes for those that cannot. The abrupt drop in consumers’ spending on plane tickets or hotel bookings is unlikely to be offset by more purchases of teleworking software instead, for instance. In the absence of good substitutes, say the authors, the economy experiences a “Keynesian supply shock”, where demand falls by more than supply. They provide another useful way to think about this state of the world: that consumption will be much more valuable in the future, as goods and services that cannot be had today become available once more. So it makes sense to spend less now, and more later.

I don’t have a problem with that analysis, but I wish these issues were framed differently. Under the gold standard it made sense to talk about “demand shocks” hitting the economy. Those would occur when there was a sudden drop in the global supply of gold or (much more likely) an increase in global gold demand. Thus an increased propensity to save or a reduced propensity to invest might cause lower interest rates. Because the interest rate was the opportunity cost of holding gold, this would boost gold demand and cause deflation. Robert Barsky and Larry Summers wrote a paper explaining this phenomenon.

But we no longer have a gold standard, and hence there’s no reason for “demand shocks” to impact nominal spending and/or prices. Instead, we have a fiat money regime, where the level of nominal aggregates is determined by monetary policy. When nominal spending rises or falls in an inappropriate fashion we have a “monetary shock” and we should call it a monetary shock. Using the term “demand shock” makes it seem like the economy was hit by some sort of exogenous shock, not bad monetary policy.

The Fed’s job is to keep inflation at 2%. If it doesn’t do so it’s not because the economy was hit by a “demand shock”, it’s because the Fed didn’t do its job. The money supply and interest rates should be endogenous, set at a let where prices are expected to rise at 2%/year.

If the bus goes over the edge into a deep canyon, it’s not because the bus was hit by a “road shock”, it’s because the bus driver didn’t do his job. But it would also be useful to install guardrails in order to make that sort of error less common.

PS. I love this article by Peter Ireland. Nice to see there are still people who understand monetarist principles.

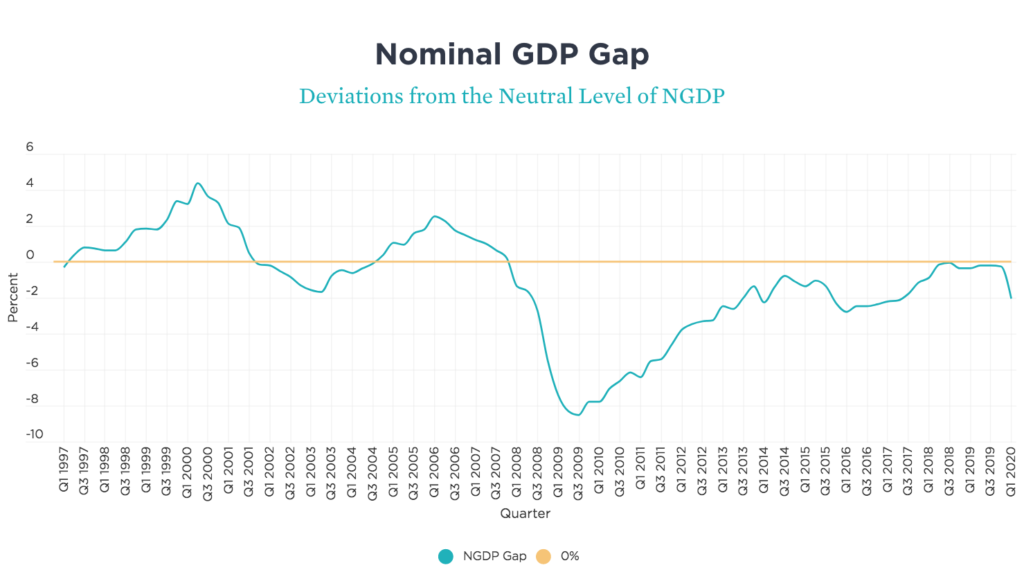

PPS. David Beckworth updated his NGDP gap model:

Tags:

15. May 2020 at 15:07

This seems to explain very well what is happening right now. You yourself said that we shouldn’t try and keep NGDP on path right now, but should focus on getting back to target by 2022.

15. May 2020 at 16:52

close, but no cigar. currency emissions are always at bottom anchored in confidence in store of value, etc, and thus in stable prices, and thus in gold. we may not have convertibility, but gold looms out there, like pluto telling orpheus, “i’ll bend my rules, but don’t look back”. pluto keeps the fed anchored to gold, so far. as jpm said, only gold is money, nothing else.

15. May 2020 at 18:07

Hi Scott,

I’m an avid reader of your blog as I try to learn more about monetary policy, but would love it if you could provide more clarity on your observations. I often struggle to interpret the meaning of what you’re saying. I have an MBA, which definitely does not equal an Econ PHD, but I’d like to think I understand some of the underlying principles of economics. However, I often leave your articles confused as to your point. Here you say:

“Those would occur when there was a sudden drop in the global supply of gold or (much more likely) an increase in global gold demand. Thus an increased propensity to save or a reduced propensity to invest might cause lower interest rates. Because the interest rate was the opportunity cost of holding gold, this would boost gold demand and cause deflation. Robert Barsky and Larry Summers wrote a paper explaining this phenomenon.”

Are you saying a increase in gold demand increases propensity to save and/or reduces propensity to invest? Why is that? And can you explain why those two would lead to lower interest rates? I’d think more investing leads to lower interest rates (more capital, less return per unit of capital).

I also don’t understand the gold standard (and perhaps economics) enough to get your comment “the interest rate was the opportunity cost of holding gold”. We’re at 0% interest rates right now and the S&P has returned 25% in the last month or so. The opportunity cost of holding gold for the last few weeks has been 100%+ annualized returns. I don’t see any clear connection between interest rates and the opportunity cost of gold.

I’m sure you over-index on economics academics in your readership, and understand if you want to cater your personal blog to them. Would love to have more color on your thoughts though for those of us with less experience to more easily understand if you’re willing. Thanks so much!

15. May 2020 at 18:11

I read the linked paper, it’s pretty similarly hard to understand for the uninitiated.

“Under a gold standard, the price level is the reciprocal of the real price of gold. Because gold is a durable asset, its relative price is systematically affected by fluctuations in the real productivity of capital, which also determine real interest rates.”

Not sure I get what they’re saying for any of that unfortunately.

15. May 2020 at 19:17

Agrippa: Actually, silver pre-dated gold as money, see China. Even today, banks in China are called “silver houses.”

While people think of the gold the Spaniards brought back from the New World, they actually brought back more silver, and most European economies had silver as specie. Of course, the little lumps of metal by themselves were worthless—the value of silver and gold is set by popular convention, as capricious as the perceived value of oil paintings or Bitcoin.

There are some industrial uses of gold, and women and fops enjoy its use as jewelry.

I could well say, “Only silver is money, nothing else.”

I rather suspect anything you can ultimately pay taxes with is real money, like a Ben Franklin you find on the sidewalk.

15. May 2020 at 20:26

I see a lot of economists failing to understand how much of the current downturn is due to a supply shock versus a demand shock. Sometimes they discuss this question directly, and at other times they imply this question by making statements about how they think the stock market is downplaying the crisis, for example. It’s interesting how few economists seem to understand the relationship between AD and AS and stock prices.

It’s quite obvious the demand shock is larger than the supply shock, because the stock and bond markets clearly indicate the demand shock is expected to last far longer. For one thing, stock prices are overwhelmingly determined by expected earnings in future years, discounted to infinity. Clearer still, bond yields wouldn’t drop decades out in response to a supply shock that will probably last no more than a year or two.

So, how can there be such confusion? It may largely stem from beliefs about stock and bond markets being irrational.

15. May 2020 at 21:55

Trying to Learn, You have the causation backwards. It’s S&I shocks that affect interest rates, and then interest rates affect gold demand.

On the Barsky/Summers quote, you start with the fact that the value of gold is 1/P under a gold standard, as the nominal price of gold is fixed. Thus if the price level falls in half then the value of gold (its purchasing power) doubles. Then you need to model the things that change the value of gold, which is what Barsky and Summers do. One important factor is interest rates, which fall when there is a negative productivity shock (like right now.)

15. May 2020 at 23:46

“I see a lot of economists failing to understand how much of the current downturn is due to a supply shock versus a demand shock.”

Is T.G.C. ‘failing to understand’?

” Given the long-run relationships that prevail between rates of growth in the quantity of money and in nominal gross domestic product (and then inflation), it has to be expected that the USA will in the next few years also suffer the highest inflation among the developed countries.”

https://mv-pt.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Extra-money-note-May-2020.pdf

16. May 2020 at 05:33

Postkey,

I won’t be surprised if US inflation rates are among the highest in the developed world over the next several years, because that would just continue the trend. However, without a change from the Fed, I expect the average inflation rate to be under the 2% target, and RGDP growth to be well below potential.

The fact is, markets are speaking very clearly on this and I think markets understand economics much better than T.G.C.

By implication then, yes I do think I have a better model in this case. If you disagree, then you should short Treasuries and see how that works out.

16. May 2020 at 06:48

Sumner, a real student of the gold standard, like Bardo, like Barsky, but not like Banksy, cuts a brain fart when he says: “Those would occur when there was a sudden drop in the ***global supply of gold*** or (much more likely) an increase in global gold demand.” (emphasis added). There’s never been a single case of a sudden drop in the global supply of gold since all the gold that’s ever been mined is still around (minus some minor losses like lost gold). You can however have a sudden new supply of gold (1849 Frisco, South Africa, Klondike, etc) in which case the purchasing power of gold drops by a factor of 1/P, where P=price of gold. Other than that, good post.

16. May 2020 at 07:08

Ray Lopez,

Supply shocks are usually about future expected supply, not existing supply. It’s about flows, not stocks. In a world growing economically, demand for gold will rise against the gold stock, ceteris paribus.

16. May 2020 at 07:54

PSST…paging Arnold Kling.

The demand curve for air travel, for example, has shifted dramatically. Common sense says that’s a demand shock.

Airline workers cannot effortlessly start producing Zoom backgrounds to make up for lost consumption of air travel. That is a friction caused by disruption to Patterns of Sustainable Specialization and Trade.

I’m a huge fan of NGDP guardrails. But in a situation where real demand has fallen by 20%, a 4% NGDP guardrail would prescribe an increase in the price level of 24%. Is that really desirable?

16. May 2020 at 08:28

Scott:

Off topic but have you seen a chart Paul Krugman produced recently? He classified employment growth post recession into 2 periods: prior to 1991 and post 1991. He observes that employment growth was robust post recession prior to 1991 and anemic post 1991. His argument is recessions prior to 1991 were Fed induced, i.e Fed tightened to rein in run away growth. Recessions post 1991 were private sectors excesses, i.e. the bubbles of 2000, 2008 etc. However, I interpret it as Fed policy has been too tight since 1991, i.e. the great moderation we got in inflation resulted in anemic employment growth. This means Fed has failed in one of its 2 mandates in the last 3 decades. I posed that question to Krugman but he has yet to respond. What is your take?

Thanks

16. May 2020 at 08:40

Todd, You are confusing aggregate demand with demand for a given product. But I do agree that it would be foolish to try to maintain stable NGDP growth during the lockdown, which is why I’ve suggested aiming for 4% growth in 2021.

LC, I agree with you, it’s tight money. Krugman defines tight money in terms of tools and instruments, not outcomes (which is the way I do.)

16. May 2020 at 10:22

I will just point out the shocks in 2008 involved commodities that are burned. So at some point people are simply going to throw up their hands and start complaining when a commodity that you buy to burn gets too expensive. So when gold is expensive you buy it and don’t burn it.

16. May 2020 at 15:09

What is the case for the asymmetric fear? Why is it easy to increase inflation variance expectations to the upside but not the downside? What is the rational given for why the tools on one side are stronger, more liquid, more speedy, or more predictable than the others?

16. May 2020 at 19:40

Scott, but even in a gold standard, fractional reserve banking can make as much money available for savers as necessary, so demand shocks shouldn’t be much of an issue there. (See George Selgin’s writing about Canada and Scotland etc.)

Of course, it you have bad regulations and bar policies, you can get demand shocks under a gold standard. Just like bad regulations and policies cause demand shocks today. (Just slightly different bad policies, of course. Because there is no central bank to screw things up in a classic gold standard.)

16. May 2020 at 20:00

agrippa postumus, are you suggesting that a silver standard or copper or iron standard would never work? The people who used cowrie shells to trade also unconsciously depended on gold?

(And if you start to make exceptions for any of those, where do those exceptions stop?)

16. May 2020 at 21:42

Todd, Scott, big short term spikes in prices are exactly what we would expect in a crisis.

A short term increase in the price level by 24% and then subsequent fall by about 20% once the crisis is over doesn’t seem that outlandish.

If we had such flexible monetary policy (and prices) the actual overall spike would probably be a bit smaller, exactly because it would incentivize people to make the kind of real adjustments and small inventions etc that Arnold Kling emphasizes.

For comparison, have a look at hard drive prices after the Thailand flooding in 2011. (Eg https://www.theverge.com/2012/1/24/2729692/western-digital-prices-thailand-floods )

Your example about airline workers and zoom background is spot on. But it’s mostly about why real GDP would fall; and why we would expect lots of inflation to keep nominal spending steady.

Scott, your argument about stabilizing expectations instead of actual nominal GDP is a good one. But the longer the pandemic drags on, the more you should bite the bullet and admit that NGDP targeting (and absence of price controls) would result in a temporary spike in prices, and that this is a good thing.

The emphasis is on temporary. Prices would fall again to their longer term trend once the social distancing is over. (The fall would begin a bit sooner, because people work out ways to do social distancing and be productive.)

Independent of that, I agree that targeting the one year nominal GDP forecast is probably the right way to go. But it would produce a temporary increase in the price level, too.

17. May 2020 at 04:50

@Michael Sandifer – thanks for that correction, but, if you’re right, then our host is assuming the “confidence fairy” exists in a hard money regime like a gold standard. If that’s true, then essentially “animal spirits” drives money supply (hard money) rather than the stock of money (flows, as you say, rather than existing stock). Logically then, it follows that a fiat (paper) money supply would also be driven by “animal spirits” rather than the amount of money. Logically, one step further, there’s very little difference in a fiat money regime and a hard money regime with respect to animal spirits. The only difference is that central banks in a fiat money regime can do a “helicopter drop” and psychologically influence ‘flow’ (animal spirits) rather than stock. You might also argue, if you are a die hard monetarist, that “animal spirits” can be influenced more in a fiat money regime than a hard money regime (debatable).

If you want to say the “confidence fairy” and “money illusion” are “animal spirits”, then you can square the circle and say money is not neutral. But Ockham’s razor would argue to me it’s better to do away with extra verbiage and just call the quantity theory of money / NGDPLT / money illusion and all the other terms simply “animal spirits”. Aka the economy is nonlinear and does whatever it wants, based on crowd psychology. Economics is not a science.

BTW Shiller at Yale got a Nobel prize for the above.

17. May 2020 at 07:45

“Todd, you are confusing aggregate demand with demand for a given product.”

I should have explained that I was using air travel as one example of a broad range of industries that have been affected by the lockdown: other examples include restaurants, movie theaters, theme parks, hotels, and concerts. Many of these industries will continue to suffer reduced demand even when all lockdowns are lifted.

Aggregate demand has indeed fallen because our consumption patterns are not seamlessly changing from locked down industries to permitted industries. Although we have had some increase in spending for Netflix and Animal Crossing (for example), it has not replaced the lost consumption opportunities.

Of course I completely agree with your policy prescriptions, but I don’t think it’s appropriate to say that aggregate demand has not fallen.

17. May 2020 at 08:57

Matthias, I agree that the Canadian system was better, but I don’t agree that this solves the problem of increases in demand for gold.

You said:

“But the longer the pandemic drags on, the more you should bite the bullet and admit that NGDP targeting (and absence of price controls) would result in a temporary spike in prices, and that this is a good thing.”

I admit that right now. My point is that NGDP targeting is not appropriate in every single case. Would you want to NGDP target during the Christmas shopping season?

I do favor NGDP targeting right now, but I want them to target future NGDP. And that’s ALWAYS been my view.

Todd, You said:

“Aggregate demand has indeed fallen because our consumption patterns are not seamlessly changing from locked down industries to permitted industries.”

You are now confusing AD with quantity demanded. I have many posts explaining the distinction. During Zimbabwe’s hyperinflation AD soared 1 billion fold upwards, even as Zimbabwe consumers bought far fewer goods.

17. May 2020 at 09:04

Ray Lopez,

Yes, stock prices are based on expected earnings, discounted to infinity, and a similar approach is applied to pricing most investments. It’s almost 100% expectations based.

I don’t think Shiller has anything useful to say about this.

17. May 2020 at 16:40

Scott,

I’m going to shed my well-earned modesty for a moment and ask if you think the Beckworth graph supports the perspective I’ve been pushing over the past 3-4 years? That is, that monetary policy has been tighter than virtually anyone acknowledges, and that RGDP growth potential was underestimated by 1-1.5%?

True, taken at face value, it largely supports your view that monetary policy was roughly correct since early 2018, but I note this approach likely often understates how far off the mark Fed policy is. These forecasts represent predictions about what level of NGDP growth the Fed will choose to have, at least implicitly. This is as opposed to representing any opinions about optimal policy, taking RGDP potential into account.

As support for this view, consider 2007. Does anyone think monetary policy didn’t get too tight until the beginning of 2008? We were already in recession in Q4 of ’07, and the financial crisis started to rear its ugly head in the late summer of ’07.

Also, are we supposed to believe monetary policy was close to optimal in late Q3 and Q4 of ’18 while the stock market was melting down and bond yields were falling?

17. May 2020 at 18:55

Scott, totally agreed. Just wanted to point out that ~20% short spike in price level is a bullet you can bite.

I thought a bit more, and the arbitrariness of the ‘one year out’ was still annoying me a bit.

Not very much, because the economy is made of humans, not math or physics. And humans have natural cycles and biology dictates that some lengths of time have significance. But still annoying me a bit.

I think I found a solution that’s less arbitrary:

I was seeing (nominal) GDP as a flow measurement that you can take at any point in time over arbitrary short intervals. And that’s often a useful fiction.

But what we actually need to stabilize is not the expectation of nominal GDP on 2021/05/18 (ie GDP on the day one year out from now), but the expected total sum of spending from now until 2021/05/18.

The argument for stabilizing the integral of NGDP instead of just the NGDP level is basically the same as your argument for why stabilizing the NGDP level is superior to stabilizing the growth rate.

The focus on the area under the curve also neatly takes care of Christmas.

The difference to vanilla NGDP level targeting is that integral NGDP targeting would suggest to make up for deviations from the target path even more aggressively:

After the pandemic, not only monthly earnings would need to be brought back up on the target path, but we would want to make up for lost earnings, too.

Companies could relatively safely run down their capital buffers to keep paying their employees, because they know that not only will earnings come back to what they were expected to be at, but they will even temporarily overshoot, so that capital buffers can be built up again.

Enough musing for now. In practice, any sensible NGDP targeting regime would already target quarterly GDP at the finest, and probably yearly GDP, anyway. And that would be good enough. Just like a long enough average inflation growth target resembles a price level target.

18. May 2020 at 09:03

Michael, Potential is hard to ascertain from this sort of graph. That’s one reason I like NGDPLT, no need to estimate potential.

Matthias, One good indicator is nominal wages. But unfortunately we lack data on that due to labor force composition changes. We need estimates of wage gains for people who still have jobs.

20. May 2020 at 01:57

“History confirms that stocks make the wrong call on future recessions almost as often as they prove a bellwether. “

https://fortune.com/2020/03/13/stock-market-recession-predictors-2020/