Is the Fed holding down growth? (Just the opposite)

I occasionally get comments suggesting that the Fed is somehow “holding down growth” in the economy. That makes me wonder if the Fed has some sort of magic dust, capable of holding down growth without leaving a trace. So let’s look at some of the traces the Fed has actually left.

Before doing so, recall that some conservative economists claim that the Fed has no first order impact on growth, because money is neutral. I don’t agree, and neither do those who claim the Fed is holding down growth.

More likely, wages and prices are sticky in the short run. The Fed can temporarily boost growth by increasing the rate of inflation, and thereby reducing the unemployment rate. I’ve argued that we should look at NGDP growth rather than inflation, which can be distorted by supply shocks.

So let’s look at the data:

1. Over the past two years the unemployment rate has fallen all the way to 3.7%, one of the lowest rates in modern history. Other employment indicators have also been quite strong, with employment rising far faster than the working age population.

2. Over the last two years, inflation has risen up to around 2%, roughly the Fed’s target.

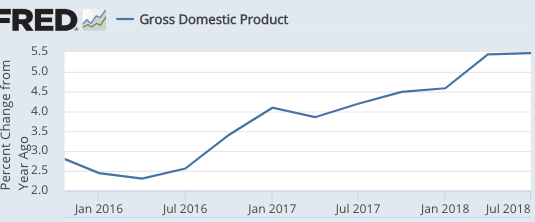

3. Most importantly in my view, the rate of NGDP growth has been increasing rapidly, from well below trend to above trend:

One can’t just argue that the Fed is holding down growth, without providing any evidence. All the evidence points in the other direction, that the Fed has been juicing the economy. Perhaps that will change in the future, time will tell. But they have certainly not been holding down growth in the recent past, precisely because they haven’t been taking the steps that would be necessary to hold down growth—slowing NGDP and inflation in order to raise the unemployment rate.

One can’t just argue that the Fed is holding down growth, without providing any evidence. All the evidence points in the other direction, that the Fed has been juicing the economy. Perhaps that will change in the future, time will tell. But they have certainly not been holding down growth in the recent past, precisely because they haven’t been taking the steps that would be necessary to hold down growth—slowing NGDP and inflation in order to raise the unemployment rate.

Some will inevitably argue that there has been a supply-side “miracle” that’s hard to see because the Fed refuses to “let the economy rip”. Supply-side miracles leave very specific tracks in the data, such as a slowdown in inflation. But inflation has been rising. And of course that doesn’t explain the strong NGDP data.

I encourage people not to go with their gut instincts, rather to look very closely at the actual data and think about what it means. You can’t just make up any old story and be expected to be taken seriously.

Everything in this post is past tense. Obviously the Fed may start holding down growth in the future, and if so we’d see the unemployment rate rise to a level above the natural rate. I can’t rule out that possibility, indeed I’d expect it to occur at some point in the next decade. But as of now it’s clear that they have not been holding down growth, and indeed have been stimulating the economy. In fairness, that stimulus was appropriate, as for years we’ve been running well below the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

PS. At the risk of saying “I told you so”, I’d like to remind readers of a half dozen posts I did around 2016-17, where I said I was not convinced that the Fed was trying to keep inflation below 2%, and that it might have been a mistake on their part. I pointed out that the consensus of private sector forecasters had also erred, not just the Fed. I said I’d defer judgment for another year to see if they could make further progress on inflation. And now we are at 2% inflation, just as the consensus of private sector forecasters and the Fed predicted. I’m willing to stop deferring judgment and come to a conclusion. I conclude the Fed really does want 2% inflation, which is the average inflation rate since 1990 and also the 30-year TIPS spread.

PPS. After a recent post on neoliberalism, some questioned my definition of the term. I was mostly responding to how others use the term. In other words:

1. Most intellectuals describe the current economic system in most developed countries as neoliberal.

2. Lots of populists on the left and the right have been running against that regime.

3. And yet the regime seems hard to dislodge, in any significant way.

Again, I was responding to the way that others define neoliberalism (usually with a negative connotation). Among opponents of neoliberalism, there is enormous surprise and disappointment that so little has changed over the past ten years. I see that disappointment frequently expressed in essays on the topic. They expected the aftermath of the Great Recession to produce the sort of change we saw during and after the Great Depression. It didn’t happen.

PPPS. China bleg: I’m looking for empirical studies of Chinese theft of American intellectual property. Any links would be appreciated.

Tags:

7. December 2018 at 17:17

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/prod2.nr0.htm

In the third quarter, productivity rose at about a 2.3% rate. The experience of the 1990s was that sustained economic growth results in a much higher productivity.

Wages-compensation are running between 2% and 3% higher YOY.

Right now wages are a drag on the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

Central bankers need no encouragement to suffocate in the economy. Let us hope the Fed lets the good times roll.

The present threat is a drop in real estate values. That’s that is close to engineering such a drop. This leads to a decrease in the endogenous money supply relatively speaking.

7. December 2018 at 18:30

Ben, Seriously? Are you trying to be annoying, or do you actually think it make sense to mix annual data and quarterly data to make a point?

7. December 2018 at 20:43

Scott,

Not to belabor a point, but if you don’t correctly assess the impact of the tax cuts on investment and therefore growth, your assessment on the stance of monetary policy is also going to be wrong.

I know you have asserted that diminishing returns will limit the impact of additional investment on growth, but to me that sounds like Malthus waking up from a 200 year nap on a hard scrabble Scottish sheep farm. The idea that this is an issue in any significant modern economic activity is just so divorced from reality that it makes me think you’re attempting parody.

7. December 2018 at 23:04

I guess part of the reason we don’t see that new New Deal type policies is that we already have so many of them on the books in rich countries?

(I’d would be interesting to make that hypothesis rigorous enough to be falsifiable. If guess something about emerging countries having still adding more welfare state as they get richer even in a generally neoliberal context could be made to do some work here?)

7. December 2018 at 23:43

Regarding neoliberalism, it seems that incremental changes away from it is hard to do. I’m getting more and more afraid that here in europe we’ll get instead violent change, as resentment and populism builds up (see the gilet jaune movement) and closet Marxists are waiting their time to capture this. Greece seems to tell another story, but it’s a small country who could not afford to be stupid anymore when siriza was elected. It could turn out differently in a bigger and decently funded country.

8. December 2018 at 02:10

Scott,

I’ve been open about the fact that I haven’t had much of a case for the claim the Fed is “riding the brakes”, as I like to say, solely using US data. I have been saying for the last year, however, that if unemployment kept falling, that would at least be evidence consistent, though not exclusively consistent with my claim. I think it’s unfair to mention people on my side of this debate without mentioning that our unemployment forecasts have been superior.

My claim that the Fed is holding down real growth is based on the all too timely correlations between the period of the Great Recession, in which monetary policy in many countries was too tight, and lingering productivity slowdowns. Yes, there’s good reason to believe real factors are also involved, but the timing is still too neat.

8. December 2018 at 02:13

Also, I should mention that the 2% inflation target is a distraction, if I’m right. We need higher inflation for at least a while. 5% NGDPLT is my preference.

8. December 2018 at 02:22

It’s too early to point to some recent disappointing jobs numbers, as they’re not yet significant, but expect that to become a trend if I’m correct and the Fed doesn’t loosen policy.

Note I’m not just talking about slowing job growth, which could be consistent with nearing a hypothetical natural rate. I’m talking about shocks to job growth, if not eventually an outright decline in jobs and forecasts.

If the Fed does loosen and we can get inflation expectatins enough above 2%, expect even lower unemployment.

8. December 2018 at 06:46

At first glance, Claude Barfield from the AEI seems to explain the IP theft story pretty fair and balanced.

http://www.aei.org/publication/chinese-intellectual-property-theft-time-for-show-trials-but-get-our-story-straight/

The two most important reports on IP theft seem to come from a special commission.

http://ipcommission.org

I haven’t look for completely independent studies yet. You think, there are any? It seems the IP commission is the best we get. It’s not that bad, I guess.

But I’m quite sure you know all this.

8. December 2018 at 07:17

Scott Sumner:

Well, okay I should have set up the figures more comprehensively.

In Q3 2018, unit labor costs are measured as up 0.9% from a year earlier.

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/prod2.nr0.htm

Okay, a year does not a trend make, but we are seeing productivity creeping up as the expansion lengthens and aggregate demand increases. The 1990s is suggestive in this regard—long expansions are positive for productivity;

Lengthening out, we have a unit labor index of 108,7 in Q3 2018, vs. 105.0 in Q3 2016, for a 3.52% increase in the last two years.

Okay, going back 10 years, we 108.7 unit labor cost index at Q3 2018, vs. 99.8 in Q3 2008, or up 9% in total over a 10-year period. Obviously, unit labor costs are up less than 1% a year in the last 10 years (Unit labor costs include all compensation, not just wages).

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ULCNFB

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/prod2.t01.htm

As it stands, I feel on solid ground in saying, as measured, labor costs are generally a drag on the Fed’s 2% inflation target.

Moreover, I am mildly confident we are seeing (I hope) first signs of a rebound, or gain, in productivity—unless the Fed tightens the monetary noose too tightly. If all goes well, we may enter a 1990s situation of rising productivity that reins in unit labor costs even with some real wage gains.

I am worried about squishiness in housing prices, and other real estate. Property values in the US may be bloaty. The Fed pulled the rug out in 2008, and you know the rest of the story.

8. December 2018 at 08:46

It’s asset prices, stupid! (No, I’m not suggesting that Sumner – or anybody else – is stupid, it’s a play on Clinton’s campaign message, It’s the economy, stupid!) What do I mean? The economy was saved from collapse in 2008-09 by the Fed’s actions in halting falling asset prices, the economy and the banks’ balance sheets were rebuilt during the great recession by the Fed’s actions in inflating asset prices, and the economic recovery was fueled by the Fed’s actions in continuing to support rising asset prices. So here we are, with asset prices looking quite vulnerable, especially housing prices but more obviously stock prices. That’s the problem with relying on rising asset prices for prosperity: how does one tame rising asset prices without risking a recession, or worse, a financial crisis. Real prosperity is a function of investment in productive capital, and not even the Trump tax cut has spurred much in the way of investment in productive capital. Signs across the country point to weakness in the housing market, the boom in housing the past several years being responsible for much of the economic growth and employment. What happens if housing hits a wall?

8. December 2018 at 09:50

dtoh, Let’s say that the tax cut has phenomenally strong effects on growth. That still has absolutely no bearing on anything I said in this post. My point is that monetary policy has been stimulating growth regardless of the supply side effects of tax cuts. The data is very clear on that point. If the tax cuts are capable of causing 10% RGDP growth, then with 5% NGDP growth you should have 5% deflation.

MFFA, France has always had violent political protests. It’s a part of their culture.

Michael, I don’t know of any economic model that would support your claim. In normal macroeconomics, falling unemployment is evidence of expansionary policy, not contractionary. What model are you using?

Your preference for higher than 2% inflation has no bearing on whether policy has been stimulative. There are also lots of people who prefer below 2% inflation. It’s like saying “I like red automobiles, therefore money is too tight.” A non-sequitor.

Rayward, You said:

“The economy was saved from collapse in 2008-09 by the Fed’s actions”

Is that a joke? The Fed caused NGDP to fall with tight money.

8. December 2018 at 10:37

Scott,

You replied: “Michael, I don’t know of any economic model that would support your claim. In normal macroeconomics, falling unemployment is evidence of expansionary policy, not contractionary. What model are you using?”

I’m considering an expansion that’s been slower than necessary since the Great Recession ended. Policy doesn’t have to be absolutely contractionary to be tight.

You also replied: “Your preference for higher than 2% inflation has no bearing on whether policy has been stimulative. There are also lots of people who prefer below 2% inflation. It’s like saying “I like red automobiles, therefore money is too tight.” A non-sequitor.”

If my view is correct, higher inflation should lead to sustainably lower unemployment. The fact that you admit that unemployment is lower now than you expected means there’s something wrong with your model.

My model may be no good, but it fits some of the data better than yours does, even if it’s just due to luck.

8. December 2018 at 12:27

Scott –

”

Rayward, You said:

“The economy was saved from collapse in 2008-09 by the Fed’s actions”

Is that a joke? The Fed caused NGDP to fall with tight money.

”

Are those two things mutually exclusive? Couldn’t the Fed have caused NGDP to fall, and then subsequently saved the economy from collapse? Plenty of people accidentally start a fire and then grab the fire extinguisher and put it out.

And off topic – I think this will make frequent commenter Ben Cole very happy:

https://www.nationalreview.com/corner/los-angeles-legalizes-street-vending/

8. December 2018 at 13:24

Scott,

I think the Fed has done well this decade, but “juicing”? The recovery has run 9.25 years with average annual RGDP growth of 2.3%. That’s some weak juice.

20 year TIPS spreads are 1.97%, but that’s CPI. Seems to me there’s a strong case for interpreting the Fed 2% PCE target as a ceiling, rather than an unbiased estimate, just based on the data.

Over the past decade, CPI has increased at a 1.56% annual clip- that’s a cumulative undershoot of the price level of 4.4%. Juicing?

It seems obvious to me that tepid growth means little chance of overheating. Why can’t the US recovery run another decade given good Fed policies, like Australia?

You say inflation has run at 2% since 1990, but I’m getting 2.3%, which includes the 1.56% over the past decade. Between 1990 and 2008, CPI averaged 2.7%. Looks like Clinton and Bush enjoyed a lot more juice than Obama or Trump.

As you’ve said, we don’t have to have a recession. But all of a sudden, lots of brainiacs have basically accepted a recession as inevitable. I don’t doubt some of this comes from people wanting to see the economy blow up under Trump, which seems to me pretty callous to the millions that would suffer collateral damage.

You should fight the “recession is inevitable” mindset that is taking hold. It’s a policy choice or mistake.

8. December 2018 at 22:36

FYI.

Richard Clarida is interesting.

Fed’s Clarida Says Risk Has Tilted Toward Too-Low Inflation

By Christopher Condon and Jeanna Smialek Bloomberg

December 3, 2018,

Central banks worldwide still fighting disinflation, he says

Vice chairman also plays down ‘Powell Put’ concept in markets

The Federal Reserve’s No. 2 official made clear in a discussion about inflation Monday that he remains more concerned about falling short of the central bank’s 2 percent objective than running above it.

“In recent decades, the asymmetry has been toward disinflation forces,” Vice Chairman Richard Clarida said in an interview with Bloomberg Television. Asked about the price impacts of globalization, he said that “we are in a world where central banks, including the Fed, are focused on keeping inflation away from disinflation.”

—30—

Was there ever a FOMC board member who publicly said inflation is too low? The recent Minneapolis Fed presidents have talked a little in that direction…but a board member?

9. December 2018 at 11:47

Michael, You said:

“My model may be no good, but it fits some of the data better than yours does, even if it’s just due to luck.”

I don’t know what your model is. You seem to be mixing up the question of whether monetary policy has been stimulative with the question of whether it has been appropriately stimulative. Those are unrelated questions.

Negation, I suppose you could make that argument, but it wasn’t implied by his claim.

Brian, You said:

“Scott, I think the Fed has done well this decade, but “juicing”?”

I think the Fed has been too tight, certainly not “juicing” during the 2010s. Reread my post. Only very recently has policy turned somewhat expansionary.

You said:

“You should fight the “recession is inevitable” mindset that is taking hold. It’s a policy choice or mistake.”

That’s exactly what I’ve been doing.

9. December 2018 at 12:59

Scott,

You replied, “I don’t know what your model is. You seem to be mixing up the question of whether monetary policy has been stimulative with the question of whether it has been appropriately stimulative. Those are unrelated questions.”

I apologize if my communication has been less clear than intended, but I’ve had the same message for over a year. “The Fed is riding the brakes” to me means that the car is moving forward, but not as quickly as it should be. I don’t recall you ever being confused about my language in prior conversations about this, of which there’ve been a few.

To try to be clearer, I think some of the low productivity growth in many developed countries has been due to insufficient stimulus, which kept a rein on investment. Hence, I think real GDP growth potential is higher than most assume in these countries. I think there’s still room for a bit of catch up real growth with more monetary stimulus.

How confident am I? Probably more than I should be. Just looking at the data, perhaps I should be 50/50 on this, at best.

But, I’m confident that you’re also over confident in your perspective, especially given that the unemployment rate had fallen further than you thought it would. There isn’t a lot of data I’ve seen to put away either argument with much confidence.

While my perspective had not been popular, it seems to be growing in popularity, and even economists at the BLS have made similar points.

9. December 2018 at 19:51

Why does anyone believe the unemployment values for the last 8 years? If we would have had strong growth, would that not be reflected in GDP or other growth metrics? Millions of low paying jobs have not unleashed a booming economy — but those jobs did help produce bad economic data points, which are now very suspect!

9. December 2018 at 20:12

Brian Donohue,

I’m not sure that it has much to do with Trump. I think a more persistent explanation is that the ascendency of Austrianism, behavioral finance, and Minskyism means that a plurality of people think that every time the Fed causes an NGDP shock it proves what a wise genius they were for warning about high asset prices. This seems to describe much of the finance sector.

10. December 2018 at 10:36

“The Fed can temporarily boost growth by increasing the rate of inflation, and thereby reducing the unemployment rate.”

I always thought the Fed increased dollar-spending, which had the effect of raising inflation. I see now that I was wrong; New Keynesian approach really is best, where the statistical tool of the “price index” is the causational arbiter. Tough to keep all this straight.

“Other employment indicators have also been quite strong, with employment rising far faster than the working age population.”

Heavens no! What with the prime-age male LFPR so high, wherever will we find the new workers for such reckless job growth?

“Most importantly in my view, the rate of NGDP growth has been increasing rapidly, from well below trend to above trend”

You’d almost think the Fed was making up for the disastrous drop in NGDP growth circa 2015-2016, which is totally inappropriate. If there’s one thing we’ve learned, it’s that the Fed should ignore levels and target *rates*.

Anyway I’m glad the Fed is taking it’s 2% inflation rate ceiling seriously. It’s fine if inflation is systematically below 2% for a decade, symmetrical policy is overrated, bad even. The best way to maximize welfare is to make sure inflation never pops above 2% year-over-year.

10. December 2018 at 14:39

“Only very recently has policy turned somewhat expansionary.”

How recently? TIPS spreads are at their lowest levels of the year, 0.1%-0.2% lower than at 12/31/2017 and below 2% across the board. That doesn’t sound very expansionary.

We know from 2008 that being several months slow on the uptake can create years of problems…

10. December 2018 at 18:26

Scott’s family ruins him. Personal thing, but IMO it’s the only reason I have for how off logic he has gone with China and Trump. Makes him unwilling to think clearly or rationally.

Nixon opened China, SO THAT Trump could bring them to heel.

Correct Libertarian Mericratic thinking holds that this not from Scot is NOT ACCEPTABLE:

“I.e., we’ll let you invest in China if you share technology. In fairness, most of the report does focus on three types of outright IP theft”

This is bad for US companies. BAD FOR US. And bad for the Chinese people.

US tech companies should OWN China’s car, airline, Uber, Airbnb, Amazon markets.

China is, in the end, just 1B people with a SHITTIER CULTURE than Texas has and as Scott knows, “Culture matters.”

If Scott

IF Scott wants to those companies to not be “American” in the long run that’s “OK,” but as long as the shareholders and management are mostly US based, expect they will align to US interests. You don’t shit where you eat.

And ALL COMPANIES RUN CORRECTLY will invade a culture and use their power to make them become like Texas.

That’s WHY we like Free Trade – if Free trade doesn’t break eggs and make other cultures become like Texas, it may not be good.

And GLOBALISM that is GOOD REQUIRES the world becomes like Texas, and this includes the “TEXAS IS BEST” attitude of right-thinking people in Texas and outside

—

What’s HILARIOUS is how much Scott makes excuses for a second-rate culture vs. Texas.

Trump is right, China 2025 is offensive to Texans, and the biggest mistake China made was pretending it was going to topple US as Earth’s greatest superpower.

China CHEATS.

And the real answer is this simple:

ALL CHINESE STUDENTS WILL BE EXPELLED FROM US COLLEGE.

This is their weakest link in short term.

China’s one-child policy assures that the PRC members who matter (their one are the ones who study in US, means when we threated their bloodline, they will break PRC to make sure their kid stays in US school.

This is the obvious gameplay outcome to anyone who understands information theory. brains are nodes. brains at top US colleges become supernodes.

Supernodes generate IP. (software)

IP wins control of nodes.

So the US will stop making Chinese nodes into supernodes unless they allow US software to control their 1B nodes.

REREAD THAT.

Sorry Scott, you are basically lost on this stuff.

11. December 2018 at 10:59

Michael, I understand that you’ve been promoting more monetary stimulus. That’s a different issue from whether the Fed has been stimulative.

Dustin, See my reply to Michael. Not sure what your comment has to do with this post.

Brian, You said:

“How recently?”

Look at the NGDP growth I provided in the post.

As far as TIPS spreads, I did a post on that quite recently. They are useful, but must be taken in context.

11. December 2018 at 11:36

But this assumes that 5.5% is too hot. Maybe it is, but it is a helluva lot easier to argue that the Fed was too tight in the first half of 2016, when NGDP was running at 2.5%.

As for TIPS spreads, whatever they represent, we can draw conclusions from their directional change, no? So, hard to say “tight” or “loose” in an absolute sense, but easy to say “tighter than it was”.

11. December 2018 at 11:46

Scott,

Yes, I understand the difference. What mistake did I make in my communication?

11. December 2018 at 14:18

“Only very recently has policy turned somewhat expansionary.”

If by recently, you mean November 9th, TIPS spreads have fallen 0.25% since then, comfortably below 2%.

Life comes at you fast. A post next April that says “maybe the Fed tightened too much” is a suboptimal outcome.

13. December 2018 at 09:44

Scott – while I broadly agree with your post, I’m curious about your thoughts that the economy is currently below potential, as measured by NGDP that never recovered to pre-recession levels/trend (as benjamin cole’s blog consistently discusses).

Unemployment is very low, but prime-age labor participation is still below previous peaks (or prime age employment-to-population ratio if you prefer, compared to 2000 peaks – participation is still a bit lower than 2007 but employment rate is equal). Kevin Erdmann tracks inflation and routinely posts about how inflation is skewed by high shelter inflation driven by supply shortages – core CPI less inflation is only 1.5%. So perhaps the Fed is mis-measuring inflation and there is more slack in the economy than they think?

In your view, how do we get back to pre-recession NGDP trend and/or prime age employment? Those are the levers that monetary policy is supposed to be able to affect right? I’m not suggesting keeping the gas down to try and juice wages, but trying to get an understanding of your view of overall economic potential.

Do you view the drop in employment/participation during the recession as caused by tight monetary policy (causing long period of substantial unemployment, and people dropping out of the labor force)? If so, can monetary policy ‘make up’ for it? Or is the damage just done and there is no recovering? Or does it matter if we get back to pre-recession trend if the current growth rate is back to a 5% level?

13. December 2018 at 11:12

Brian, You said:

“As for TIPS spreads, whatever they represent, we can draw conclusions from their directional change, no?”

Not if they reflect large oil price changes.

Michael, I said recent Fed policy has not been holding back growth. You said you would have preferred a more expansionary policy. Both might be true.

Ben, Getting back to the pre-2008 NGDP trend line made sense in 2009 and 2010, it does not make sense after wages and prices have adjusted to the new lower trend line. It would further destabilize the economy.

As far as labor force participation, the rate for men has been declining since the 1950s, so it’s not just due to the recession. Boomer retirements also play a role. The labor market is very strong, with companies unable to find workers. What problem are you solving with more stimulus? Are you telling me there are lots of workers who are not even searching for jobs right now because they feel there’s no hope for finding a job? Seriously?

I don’t understand Kevin’s argument on shelter inflation. The Fed targets total inflation, not inflation minus shelter. Is he saying that inflation minus shelter better predicts future inflation than does overall core inflation? What is the evidence?

And what does “skewed” mean? Is inflation also “skewed” by the positive supply shock from tech, which holds inflation down?

13. December 2018 at 13:49

RE: labor force participation, in fairness I did mention prime-age, specifically because of the boomer retirement factor. And yes, male participation has been down long term – no arguments there.

However, the long term decline in male participation seems somewhat tied to the business cycle – periods of stabilization followed by drops during recessions. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=mpXC. My (amateur) hypothesis is along that during recessions you get a lot of ‘creative destruction’ as firms shed inefficient labor – but because of the increasingly slow recoveries the last several cycles, a lot of these workers simply leave the work force altogether. The trend is long term, but it seems strange to leave out the role of monetary policy/recessions entirely.

It was broadly a question of how you see labor market slack and economic potential. I think the employment-participation ratio is still depressed relative to the 2000 peak, but would agree with you that wage growth, inflation, and unemployment levels suggest a very tight labor market. Prime age participation has flattened in 2018 instead of continuing to go up like from 2015 through 2017 – if there was much more slack per my initial reading of the employment-population ratio, I’d have expected the unemployment rate to stay around 4.0% and to see participation continue to rise. It seems like those workers may just be lost for good.

RE: kevin’s shelter inflation, my take is that the argument is that shelter inflation is the result of a real supply shortage, while ‘core inflation’ is intended to measure the overall price level and the impact of monetary policy. We exclude food and oil from core inflation because they similarly provide unreliable data on monetary policy stance right? At least that’s my interpretation of the argument. I believe he’s suggested (I cannot find a good link) that high shelter inflation ‘skewed’ core inflation in 2007 to make the Fed think that monetary policy was looser than it truly was, I guess that’s the ‘evidence’. So NGDP growth fell from a 6.6% rate in 2006 to 4.6% by the end of 2007. Inflation was humming right north of 2% so the fed didn’t adjust rates as NGDP fell – because shelter inflation was up at 4%. It is quite possible I’m misunderstanding him, but otherwise i’m not really sure why he keeps posting about it the way he does. Your point re: tech is a good one, of course. I’m not trying to make any major arguments, just an amateur trying to learn.

14. December 2018 at 11:06

Ben, You said:

“We exclude food and oil from core inflation because they similarly provide unreliable data on monetary policy stance right?”

There are actually two issues here, supply vs, demand side inflation, and transitory vs permanent.

I mentioned tech because that’s also supply side, but it holds inflation down. So if your argument is “get rid of supply side effects” you’d have a stronger argument for getting rid of tech than housing (which is at least partly demand side.)

If your argument is based on transitory vs. permanent, then I don’t see why housing would be lumped in with food and energy, which really are transitory. I don’t see a good theory for excluding housing, but not tech.