I’m in Jason Smith’s doghouse

Jason Smith is trained in physics, and has recently tried his hand at economics blogging. Perhaps inspired by Matt Yglesias and Britmouse, Jason noticed that an economics degree is not required to do good economic analysis. But he went even further than the other two, creating a revolutionary new type of economics called “Information Transfer Economics.” Although I’ve tried to understand his model, it’s all way over my head. He knows a lot more math than I do.

Jason is now discovering just how macro research is done, and as a result Mark Sadowski and I are in his doghouse. Literally:

And that picture is one of the nicer things he had to say. The dog is more handsome than I am, and probably more skilled at time series analysis. But this isn’t too nice:

And that picture is one of the nicer things he had to say. The dog is more handsome than I am, and probably more skilled at time series analysis. But this isn’t too nice:

This is just garbage analysis.

Basically we did not provide the best possible study of austerity. For instance, we did not distinguish between countries at the zero bound, and those not at the zero bound. Guilty as charged.

So what’s my defense? Here’s how I look at it. The Keynesians did several studies of the relationship between austerity and growth that were highly flawed, for too many reasons to mention. Confusing real and nominal GDP. Mixing countries with and without an independent central bank. Wrongly assuming correlation implied causality. Mixing countries at the zero bound with countries not at the zero bound. Just a big mess.

And then the Keynesians did blog posts suggesting that these studies provided some sort of scientific justification for the claim that austerity slows growth. Mark and I thought it would be interesting to at least separate out the countries with an independent central bank, from those that lacked the ability to do monetary offset (i.e. the eurozone countries.)

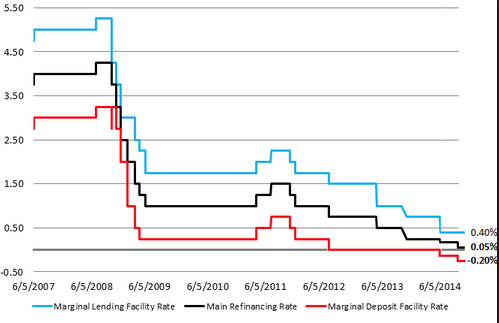

I find it interesting that our critics are outraged that we included some non-zero bound countries, when the Keynesians did as well. For instance, the 18 eurozone countries were certainly not at the zero bound for the vast majority of this period. Their main interest rate fluctuated between 0.75% and 1.50% between early 2009 and 2013. (It’s now roughly zero) And yet all that time Keynesians were squawking about how “austerity” was slowing growth in Europe. It seemed logical to assume that if the Keynesians were making this claim, then they were assuming that their model also applied to countries with low but positive interest rates. Indeed that they assumed it even applied to countries where the central bank was in the process of raising interest rates to reduce inflation. I’m happy throwing out the 18 eurozone countries. But of course if you do so then the empirical support for their austerity theory collapses. Is that what my critics want?

Mark improved on previous studies by looking at both NGDP and RGDP, and by separating out countries with independent monetary policies from those that lack independent monetary policies. He showed that if you do so then the Keynesian results go away. Maybe even further improvements could resurrect the Keynesian model. If so, I’ll take a look at the results. But as of now I don’t know of any credible support for Keynesian interpretation of the effects of austerity during the Great Recession.

PS. Mark has another good post over at Marcus Nunes’ blog.

PPS. The graph below shows ECB rates, with the middle one usually cited as the policy rate. The lower (deposit) rate did hit zero in 2012, but there is no zero bound on the deposit rate. The increase in rates during 2011 was done to control inflation, and eventually caused a double dip recession. Doing fiscal stimulus when a central bank is trying to reduce inflation is about as effective as slamming your foot on the accelerator when the transmission is in neutral.

Tags:

19. June 2015 at 18:20

A simple comparison: Spain & Poland. Neither at the ZLB but one with independent MP:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/02/26/austerity-only-explains-outcomes-when-monetary-policy-is-absent/

19. June 2015 at 18:23

A take on “Expansionary Fiscal Austerity vs Contractionary Fiscal Expansion”:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/03/21/india-brazil-expansionary-fiscal-austerity-vs-contractionary-fiscal-expansion/

19. June 2015 at 18:26

Mark S. sent me this. Should be of interest to Jason:

https://orderstatistic.wordpress.com/2014/03/21/why-are-physicists-drawn-to-economics/

19. June 2015 at 18:41

“For instance, we did not distinguish between countries at the zero bound, and those not at the zero bound. Guilty as charged.”

Yes, its true you didn’t do that. But did that affect the overall conclusions ?

Say you want to compare two views:

1. monetary policy is effective except at the zero bound

2. monetary policy is effective even at the zero bound

You take a sample of 100 countries , some of them at the zero bound and some not (and you assume away all noise in the system)

Then:

if view 1 is right: you will see a correlation between austerity and contraction

if view 2 is right: you will see no correlation between austerity and contraction

And Mark’s datasets show that view 2 is right.

Did I miss something ?

19. June 2015 at 18:42

Lol… He’ll be surprised about this post I think. BTW, I’ve got dibs on that meme for my avatar, so don’t get any ideas.

19. June 2015 at 18:49

Marcus, Thanks, I’m glad to see Chris House is blogging again.

Market Fiscalist, That’s right, but I suppose the counterargument is that when you don’t have a lot of data points, putting in some that don’t directly test the theory reduces the efficiency of the test. To me the natural reply is that Mark was doing the same sort of thing as the Keynesians, but better.

19. June 2015 at 18:58

Bravo to Sumner for taking up my suggestion in the previous post that he defend himself in J. Smith’s post. Seems Sumner is more flexible than I assumed. Who knows, perhaps someday he will show his work that the Fed moves the economy (still waiting on that special request).

Sumner’s defense is understandable: “the Keynesians did the same thing [i.e., flawed analysis]”. So we can agree on this then: a pox on both their houses (Keynesians and Monetarists).

19. June 2015 at 19:02

“The dog is more handsome than I am and probably more skilled at time series analysis.”

Lol,… Well I’m sure that’s true for me. Scott, no one can say you don’t have a sense of humor.

19. June 2015 at 19:15

…and actually I think you’re selling yourself short. I think you could give that pooch a run for his money… Looks wise anyway. XD

19. June 2015 at 19:36

Looks like you ran into a real life Sheldon Cooper. Maybe you should call his MeeMaw.

19. June 2015 at 22:07

FWIW, there’s been quite a bit of soul-searching by the RBA recently over whether monetary policy is losing its effectiveness – despite the official Australian cash rate only recently being reduced to (still) 2%. The RBA concluded that re consumer spending:

“Consumption growth has picked up since 2013. But it is still a little weaker than suggested by historical experience. This may reflect a number of factors including some variation in the ways that the different channels of monetary policy are affecting households according to their stage in life. Some indebted households appear to be taking advantage of low interest rates to pay down their debts faster than has been the norm, perhaps in response to weaker prospects for income growth. Those relying on interest receipts may feel compelled to constrain their consumption in response to the relatively long period of very low interest rates.”

http://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2015/sp-ag-2015-06-15.html#f6

The RBA expressed somewhat great frustration re business investment:

“Detailed discussions with managers and survey evidence indicate that the lack of direct interest rate sensitivity partly arises because Australian firms typically use effective discount rates that are high and sticky to evaluate capital expenditure opportunities. This reflects the use of hurdle rates that are considerably higher than the weighted average cost of capital and are adjusted infrequently, or a requirement that any outlay must be expected to be recouped within a few years.”

http://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2015/jun/pdf/bu-0615-1.pdf

20. June 2015 at 01:28

“As a result real GDP in Greece fell by 27 per cent; unemployment reached 28 per cent; wages fell 37 per cent; pensions were reduced by up to 48 per cent; and government employment fell 30 per cent.” —from an op-ed in The Telegraph, by a guy named Lamont.

Sheesh. Maybe time to help the Greeks instead of teaching them a lesson?

20. June 2015 at 01:36

OT: Scott, you ever read Woody Guthrie’s autobiography, Bound for Glory? I recommend it. Most underrated work of American literature, IMO. Best literary account of The Depression (literary without literary pretense.) The Grapes of Wrath is a shallow dramatization of that same lost world which Guthrie brings to life in 3D. I know you’re a huge Dylan fan, so I suspect you’d recognize the greatness in this underrated work. If for some reason you haven’t read it, you should and maybe comment on it here.

20. June 2015 at 02:48

@Rajat

“There are other significant ‘anomalies’ that have challenged the old as well as the new mainstream approaches. While theories place great store by the role of interest rates as the pivotal variable that has significant causal force, empirically they seem far less powerful in explaining business cycles or developments in the economy than theory would have it. 4 In empirical work, interest rate variables often lack explanatory power, significance or the ‘right’ sign.5 When a correlation between interest rates and economic growth is found, it is not more likely to be negative than positive. 6 Interest rates have also not been able to explain major asset price movements (on Japanese land prices, see Asako, 1991; on Japanese stock prices, see French and Poterba, 1991; on the US real estate market see Dokko et al., 1990), nor capital flows (Ueda, 1990; Werner, 1994) – phenomena that in theory should be explicable largely through the price of money (interest rates). Furthermore, in terms of timing, interest rates appear as likely to follow economic activity as to lead it.”

http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/339271/1/Werner_IRFA_QTC_2012.pdf

20. June 2015 at 04:48

OT: on Fed economists Ekaterina Peneva and Jeremy Rudd’s new paper: “They conclude that “price inflation now responds less persistently to changes in real activity or costs; at the same time, the joint dynamics of inflation and compensation no longer manifest the type of wage-price spiral that was evident in earlier decades.”

Translation: wages, even if sticky, are irrelevant today for inflation (and hence NGDP, recall real GDP + inflation = NGDP), hence MM is a dead letter.

20. June 2015 at 05:09

I’m still unclear about the view of MM on the usefulness of “fiscal policy” (defined in some change-in-deficit way, not as departing from the tax-and-spend-when-NPV-of-expenditures-is-greater-than- zero rule). Is it that “fiscal policy” can have no effect if there is an independent central bank or is it that “fiscal policy” can have no effect only if that independent central bank is pursuing an optimal or certain kinds of non-optimal monetary policy rules?

This is related to the question of whether, in your view, Keynesians have been wrong because they have an incorrect model of how monetary policy affects income or because when making predictions, they have misjudged what monetary policy will do in response to “fiscal policy?”

20. June 2015 at 05:18

Bill, Pop culture references are wasted on me. I don’t keep up.

Rajat, Thanks for that link. I guess when you assume that monetary policy works through interest rates, and the world doesn’t behave as you’d expect, you assume that monetary policy is “losing its effectiveness.”

Ben, Yes, but first the Greeks need to help themselves. You’d want to help an alcoholic, but also ask them to stop drinking.

Dirk, Thanks for the tip.

Postkey, Exactly.

Ray, You said:

“Translation: wages, even if sticky, are irrelevant today for inflation (and hence NGDP, recall real GDP + inflation = NGDP), hence MM is a dead letter.”

You’ve got causation so mixed up I wouldn’t even know where to start. It’s like a shoelace tied up into a giant knot. Where did you get the idea that MMs think wages cause NGDP?

20. June 2015 at 05:20

@ Market Fiscalist

One has to define “monetary policy.” Often people use “monetary policy” to mean, manipulation of the interest rate on ST government securities by buying and selling them. It could mean buying and selling longer term assets to affect other rates. It could mean announcing that the central bank would do X until the economy shows a certain result and, if believed, never having to do X.

20. June 2015 at 05:23

Thomas, You asked:

Is it that “fiscal policy” can have no effect if there is an independent central bank or is it that “fiscal policy” can have no effect only if that independent central bank is pursuing an optimal or certain kinds of non-optimal monetary policy rules?”

The latter. I would add that if policy is non-optimal, the multiplier can be either positive or negative, depending on the specific type of non-optimality.

I wouldn’t exactly say the Keynesians have misjudged the response of monetary policy, I’d say they’ve ignored it. Or perhaps they’ve assumed that interest ARE the stance of monetary policy.

20. June 2015 at 05:25

Here I present a “back of the envelope illustration” of the monetary offset:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2014/03/02/a-back-of-the-envelope-illustration-of-the-monetary-offset/

20. June 2015 at 05:40

@Bill Reeves,

Reference not lost on me. LOL.

20. June 2015 at 05:41

If we are reduced to looking at the intersection of ZLB and ICB, i.e., US and Japan, both of these cases have shown symptoms that reject the Keynesian model and favour the monetarist one:

1) the “test” of austerity in 2013

2) the weakening of the yen

20. June 2015 at 06:28

@Sumner: “You’ve got causation so mixed up I wouldn’t even know where to start. It’s like a shoelace tied up into a giant knot. Where did you get the idea that MMs think wages cause NGDP?”

You, Scott. I got the idea from you. Wasn’t it you a while ago that said since wages are like 67% of GDP, then companies firing workers in a downturn will aggravate a recession, unless NGDP was pumped up by (supposedly) having the Fed print more money, since wages were sticky? That was you. Be like Alexander the Great, cut the Gordian Knot, Scott.

20. June 2015 at 07:40

Mark did work I cannot do in your adjacent post (congrats on PHD Mark as well). What I would be interested in seeing is the addition of current account, and changes in private debt added into those tests of austerity. Essentially the latter would be applying Wynne Godley’s SFB to see what happens.

20. June 2015 at 09:05

Austerity, Swedish style;

http://www.swedishwire.com/politics/19641-swedens-financial-watchdog-to-force-households-to-reduce-mortgage-debt

———quote——–

Sweden’s financial regulator said it probably has enough political backing to proceed with a plan that would force households to reduce their mortgage debt, Bloomberg reports.

“We are quite hopeful as there’s been support for a requirement from both government and opposition,” said Martin Noreus, acting head of the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority.

An amortization requirement is still the best way to address accelerating credit growth and rising housing prices in Sweden, Noreus said.

———endquote———

20. June 2015 at 09:48

Ben, Yes, but first the Greeks need to help themselves. You’d want to help an alcoholic, but also ask them to stop drinking.

I am really surprised that this has been your take on Greece. It’s like Lister saying that the really bad hospitals need to hire better doctors before worrying about their germ problems. Greece surely has plenty of structural cracks, just as it had in 2006 and 1996. But nothing, not its unsustainable debt, not its flawed tax system, not its pension incentives, not its labor market rigidity, requires it to run 25-30% unemployment, 50-60% youth unemployment, and 75% employed people who say they are under-utilized. In some ways Greece has worsened during this period when resources have gone horrifically idle, but in other ways it has actually improved. If Gabon and Mexico and Bangladesh or old-Greece don’t require half their economies frozen in place to continually try to address their respective structural problems, neither does current Greece.

The idea that the nominal damage has already been done does not compute. The current frozen-economy equilibrium is here and now and it is a disaster with damages that accumulate to something just barely above a worst-case scenario. The question shouldn’t be whether a nominal reset would benefit Greece, but what the costs would be given the obvious difference between a simpler Argentine-like de-pegging and abandoning the Euro for a new MOA. Nobody would argue that this is simple, but where are the people screaming for a more explicit conversation about the risk-reward on this topic? 99% of the conversation is about debt adjustment, stimulus versus austerity, and structural reform bargaining. So little of the public creative discourse is about thinking of ways in which the EU could help contribute to less chaotic currency regime change. And this is because so few people seem to think that there is still a big nominal problem. After all, wages have declined, right?

I would think you would at least be reminding people that while difficult, nominal rigidity is surely still a big part of the boot on Greece’s throat. Just because Greece has the worst immune system in the Euro doesn’t mean it isn’t a huge victim of the ECB’s HVAC system. Sure, Austria looks better by comparison, but stick Argentina or maybe Turkey on the Euro and suddenly Greece wouldn’t seem so uniquely fragile to the nominal winds.

20. June 2015 at 09:56

Market Fiscalist:

“Say you want to compare two views:

“1. monetary policy is effective except at the zero bound

“2. monetary policy is effective even at the zero bound

“You take a sample of 100 countries , some of them at the zero bound and some not (and you assume away all noise in the system)

‘Then:

‘if view 1 is right: you will see a correlation between austerity and contraction

“if view 2 is right: you will see no correlation between austerity and contraction

“And Mark’s datasets show that view 2 is right.

“Did I miss something ?”

OK. First, suppose that there is some medicine for which it is claimed that it boosts egg production in hens, but has no effect on egg production in roosters. Another view says that it has no effect on egg production in either hens or roosters. To test the views you make a sample of 100 chickens, including both hens and roosters. Does that make sense? Of course not. You should only include hens in your sample.

Second, the views you stated are less complex than those that Sumner stated, so the above may not, and does not apply to testing them. In fact, you should sample both countries that are at the zero lower bound and countries that are not, but you need to keep them differentiated, and not mush them together.

Third, in your example, seeing no correlation does not mean that view 2 is right. What it means is that the case for view 1 has not been made. Maybe because too many roosters were in the sample, maybe not. No evidence of an effect is not the same thing as evidence of no effect.

20. June 2015 at 10:05

@dlr – don’t you hate it when your hero doesn’t confirm to your ideal, and speaks out of both sides of their mouth? But your hero is a lot smarter than you. Years of being wrong has taught them not just to be ambiguous (that’s for tyros), but to simultaneously hold true two opposite hypotheses as a survival mechanism.

Sumner will never be proven wrong (neither will Krugman). It’s the nature of being a wily economist.

20. June 2015 at 12:08

It might also be useful to go back to the genesis of the previous post.

Here’s the original post where I pointed out that, when currency regime is taken into account, Krugman’s results concerning fiscal consolidation and real gross fixed investment break down:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=24180

And here’s the post where I responded to Krugman when he argued currency regime matters when considering the relationship between debt levels and borrowing costs, only four days later:

http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=24282

In other words, Krugman did a very similar thing to what I did in the first link above, and to what Scott and I did in the previous post. He separated out the euro area members from the noneuro members to show that the relationship between debt level and borrowing costs disappears when you focus on countries with their own currencies.

In short, currency regime matters a great deal, but only when Krugman thinks it should.

20. June 2015 at 16:40

Thanks, Scott. I sort of thought that if policy is non-optimal, the multiplier can be positive. I had not considered the possibility of negative. How does that work? Do you mean that if fiscal policy raises the discount rate by which NPV of expenditures is calculated leading to a smaller deficit/larger surplus, the monetary authority could increase its purchases of assets (not ST treasures if those rates are at the ZLB) by more than the amount of fiscal contraction or do something else, enough to increase growth that had been below its target?

You are probably right that “Keynesians” don’t analyze that kind of scenario. In one of the quotes Krugman said that monetary policy ought to be doing more but it couldn’t/wouldn’t compensate for the sequester. Too bad we do not have his model to see exactly which he wanted to claim and consequently see how it performed if actual monetary policy was different from what he assumed it would be (if indeed the model included the monetary policy variables that the Fed used to offset the sequester+), and how it is different in structure from the one a MM might have used to correctly predict no decline in growth from the sequester+.

20. June 2015 at 16:47

Scott Sumner: my counter-analogy is, “Do you treat an alcoholic by applying starvation?”

20. June 2015 at 21:29

@ThomasH: “I had not considered the possibility of negative [fiscal multipler]. How does that work?”

You may find more enlightenment at this post by Sumner, in particular the 2nd paragraph of point #3: “If they had done level targeting in 2009 to make up for a lack of fiscal stimulus, in my view the recovery would have been even faster. So more than 100% monetary offset is perfectly possible. As long as we are in the realm of irrational behavior, anything is possible.”

In other words, because some fiscal stimulus was done in 2009, even less monetary stimulus was done, and so therefore the net fiscal multiplier was negative (compared to the counterfactual world).

“the monetary authority could increase its purchases of assets (not ST treasures if those rates are at the ZLB)”

You have a very different macro model than MM/Sumner. Monetary policy doesn’t work (much) through the interest rate channel, so the ZLB is mostly irrelevant. It works through the Hot Potato Effect (HPE) and forward expectations. So yes, the two concrete steps would be OMOs of ST Treasuries, and clear communication about the future path of monetary policy.

21. June 2015 at 08:11

dlr,

“Sure, Austria looks better by comparison, but stick Argentina or maybe Turkey on the Euro and suddenly Greece wouldn’t seem so uniquely fragile to the nominal winds.”

That’s a feature, not a bug. There’s lots of animosity about the most influential Economist of our day – Robert Mundell – but his theoretical discussion of what Greece is going through was totally proving true.

Greeks themselves WANT to stay in Euro, their govt (supported by slightly fewer people) also wants more control over it’s currency, the Euro.

This is a big decision, bc ultimately, if they don’t get movement, they have to choose.

This is a big choice. It’s SUPPOSED to be like this, so that Turkey and Argentina style governments KNOW they can’t join AND for their people to ask “why?”

21. June 2015 at 08:20

One way I think about the EU, is in US allowing other countries (Mexico, Canada, Israel, Scotland) to become US states.

They’d get US Defense perimeter protection, they’d get free movement (and US citizenship) to other US states, and they’d lose their currency. The rest of the stuff is simply about what rights we leave to states (states get more rights), but states not running budget deficits is a fact of life.

I happen to think all of those countries would get more out of being US states, and they do not all speak English.

So it’s easy to see the decision that Greeks need to make amongst themselves.

21. June 2015 at 12:48

Thanks Marcus.

Robert, Yes, and in the case of Japan, unemployment fell significantly despite the austerity.

Ray, Yes, I said that, but that has nothing to do with wages causing NGDP. The Fed causes NGDP, and then if wages are sticky, NGDP causes RGDP. If wages are not sticky, then NGDP doesn’t cause RGDP.

Matt, Hopefully someone does that.

Patrick, I’d want to see the details.

dlr, We agree more than you assume. I’ve done lots of posts criticizing the ECB, some quite recently. But the most effective way of criticizing the ECB is not to say “do more inflation to help Greece,” but rather “do more NGDP growth because the entire eurozone has insufficient NGDP growth.”

But I’m also really angry at this government. Last year both Greece and Spain were seeing early signs of recovery. Now Spain is still recovering while Greece is back into recession. This government has been a disaster. They’ve made the structural problems worse.

Greece was in good shape in 2006 only if you ignore the fact that their government were engaged in criminal fraud, borrowing far more money than they admitted to borrowing. Greece is now paying the price of its horrible policies preceding the recession, when it ran up a massive government debt.

My first choice would be to fix the nominal problem, but:

1. The ECB won’t do that.

2. The Greek public wants to stay in the euro.

Given those realities, austerity is the only option, unless they can convince the Europeans to just transfer large amounts of money to Greece, indefinitely, so that Greece can keep paying is public employees and pensioners far more than many of the countries bailing them out pay (like Slovakia.)

Thomas, Yes, they might under or overshoot their target, either is possible.

Ben, I still want the ECB to do more, no disagreement there.

21. June 2015 at 13:32

Scott, you’re right we agree on plenty. But this…

Greece was in good shape in 2006 only if you ignore the fact that their government were engaged in criminal fraud, borrowing far more money than they admitted to borrowing. Greece is now paying the price of its horrible policies preceding the recession, when it ran up a massive government debt.

…is too much morality play too little utilitarian for me. I can name plenty government regimes that have and/or currently do engage in fantastic amounts of “fraud” without needing to “pay the price” of crippling world-leading unemployment for six plus years and a fifteen year regression in output. Argentina sometimes looks like it is directly targeting 30% unemployment but can’t seem to reach it except when it pegs the ARS really poorly. The “price” for fraud is both stunted ongoing production during the fraud and then, probably, a period of chaotic adjustment and higher real borrowing costs when the fraud is “uncovered.” It ain’t this. If 50 frail people catch the flu but only 1 dies because they happen to be in a place where people practice witchcraft medicine, the most useful “cause” of death is witchcraft…not the flu.

My first choice would be to fix the nominal problem, but:

1. The ECB won’t do that.

2. The Greek public wants to stay in the euro.

Given those realities, austerity is the only option, unless they can convince the Europeans to just transfer large amounts of money to Greece, indefinitely, so that Greece can keep paying is public employees and pensioners far more than many of the countries bailing them out pay (like Slovakia.)

This sounds suspiciously like what a Keynesian stimulus proponent might have thrown at you for pushing NGDP level targeting. You are right that it almost surely isn’t going to happen. I just don’t think the gadflys should starting compromising (or moralizing!) before they ever scream their message out. Especially the technocrats. Because almost nobody else is. Think about this. We might even end up in a solution where Greece suffers most of the disruption of leaving the Eurozone, default, and capital controls, but still ends up with a terrible nominal equilibrium.

21. June 2015 at 16:02

Benjamin Cole:

“Scott Sumner: my counter-analogy is, “Do you treat an alcoholic by applying starvation?””

My counter-counter analogy is, “Do you treat an alcoholic by applying more alcohol that you falsely believe to be food, and, do you treat an alcoholic by denying him the choice of what he eats?”

21. June 2015 at 19:58

@ Ben Cole

One can’t treat an addict that is dellusional

22. June 2015 at 06:02

dlr, The only reason I feel a need to moralize is that the defenders of the Syriza government do the same. I’d prefer not to moralize, and just treat this as a technical problem.

Here’s the problem I have. I see people on the left arguing that the Europeans should bail out Greek taxpayers because the Greeks are suffering and they feel sorry for the Greeks. That’s horrible reasoning. Maybe the Greeks should be bailed out, but for God’s sake not because they are suffering. People are suffering all over the world, usually far worse than in Greece. And if they are going to bail out the Greeks it’s reasonable to ask Greece to reform its economy in exchange for the aid. Instead Syriza is going the opposite direction, undoing the previous reforms. That’s insane.

At the same time I have lots of articles criticizing the ECB, indeed I get the exact opposite complaint from conservatives. They say I just want to paper over reckless borrowing from European governments. I try to address each issue in as a precise a manner as possible.

BTW, My prediction is that the two sides will reach an agreement, and then Syriza will cheat on the agreement, and then the crisis will flare up again.

22. June 2015 at 06:37

fair enough Scott, but when even the purest technocrats have to angle their shots around all the other balls on the felt, there’s no one left to close their eyes and shoot straight.

BTW, My prediction is that the two sides will reach an agreement, and then Syriza will cheat on the agreement, and then the crisis will flare up again.

I think the same. It may not even be “cheating” so much as near-immediate regret and reneging. What will it feel like to be a mid-level or lower Syriza supporter the morning after, if we assume no magical V-shaped recovery? It’s one thing to feel you’ve acquiesced to avoid a known demon, but when you have only a nebulous idea of what you avoided in the first place, relief will fade pretty quickly. Meanwhile, the “concessions” you’ve made to the status quo will be obvious and concrete.

22. June 2015 at 09:25

Realistically, the “Information Transfer” model doesn’t make any sense anyway, even less than MMT — people don’t transfer information, they transfer value, the two are not the same thing. But we see nonsense theories all over in both economics and physics, they tend to persist as long as they’re 1) vague enough to avoid immediately disproval and 2) ideologically useful, especially to the left that dominates academia and gov’t.

One flaw in these austerity analyses generally is that they don’t break out effects of tax increases versus spending cuts — nearly all the “anti-austerity” critics actually support the former and only object to the latter.

22. June 2015 at 09:29

Also, thanks marcus, great posts! The Poland/Spain contrast is one to bookmark.

22. June 2015 at 18:43

@TallDave, you write:

“Realistically, the “Information Transfer” model doesn’t make any sense anyway”

You might be correct. However, he’s one of the few macro bloggers that can clearly describe what evidence would falsify his claims. That’s a prerequisite for any serious claim about reality.

If someone can’t describe clearly what evidence would falsify their claims, then it’s likely they’re not open to belief revision based on the evidence.

What evidence would demonstrate that your beliefs are wrong?

23. June 2015 at 16:49

Tom, I’ve done posts on what evidence would contradict MM.

23. June 2015 at 17:44

Nah, that evidence would just be chalked up to bad regulations, technology, or chance.

We can’t observe the test.

24. June 2015 at 10:46

Scott, you write:

“Tom, I’ve done posts on what evidence would contradict MM.”

Great! What should I search for? Thanks.

25. June 2015 at 01:49

Great to see the response to Jason’s post – not sure if it is wise but certainly honest and proud thing.

Already said but it is not a strong argument that other side did it too. Why still arguing the analysis is okay if it is not? Should you edit the post and link Jason’s post for the counter arguments?

25. June 2015 at 01:54

But this is not wise:

“Here’s the problem I have. I see people on the left arguing that the Europeans should bail out Greek taxpayers because the Greeks are suffering and they feel sorry for the Greeks. That’s horrible reasoning. Maybe the Greeks should be bailed out, but for God’s sake not because they are suffering. People are suffering all over the world, usually far worse than in Greece.”

For God’s sake hopefully this is just a simplification beyond being human.

Are you saying that because one can’t help everybody it is a reason not to help anyone? While maybe true in a strict sense, most of us are only humans and can’t be that black and white. Would you help your friend if needed – why? Or are you totally altruistic?

25. June 2015 at 06:01

Tom, That’s the problem, I’ve never found a good way to search my 1000s of posts. Sorry. I can say that if the Fed stabilized NGDP and RGDP became more unstable, that would refute. Or if they targeted NGDP futures and NGDP became more unstable that would refute. A recession in 2013 would have refuted part of my theory (offset.)

Jussi, You said:

“Already said but it is not a strong argument that other side did it too.”

If people want to argue that Mark’s study is totally worthless, and hence all the studies Mark is criticizing are totally worthless, I’m fine with that. Because that means there’s zero evidence to support the Keynesian view of fiscal policy during the Great Recession. Are you OK with that?

You said:

“Are you saying that because one can’t help everybody it is a reason not to help anyone? While maybe true in a strict sense, most of us are only humans and can’t be that black and white. Would you help your friend if needed – why? Or are you totally altruistic?”

OK, now we are getting somewhere. As I said, utilitarianism is not enough. We can look at other arguments. Is Greece Germany’s “friend?” Well how would I feel if I found out that a friend ran up gambling debts and stole $500 from my wallet to pay them off. Would I still consider him my friend? Maybe, if otherwise the mafia would kill him. But if the only downside was lower consumption for my friend then I’d stop helping him. Greece faces lower consumption, Africans face death. I know where my charity would go.

I mean for God’s sake the Syriza party just rehired 1000s of employees of a corrupt government owned TV station. Maybe they should first help themselves, before the rest of Europe pitches in. Socialism is not the solution for Greece’s problems, just as more wine is not the solution for an alcoholic’s problems.

26. June 2015 at 06:06

“If people want to argue that Mark’s study is totally worthless, and hence all the studies Mark is criticizing are totally worthless, I’m fine with that. Because that means there’s zero evidence to support the Keynesian view of fiscal policy during the Great Recession. Are you OK with that?”

What’s the logic here? There are bad studies and good ones. Some zealots and some trying to make a real contributions. Noise and true values. I would be worried not to see any evidence for all the mainstream views in a such complex discipline.

***

“As I said, utilitarianism is not enough.”

I think you said sorry is not enough. Why utilitarianism is not enough?

Why don’t you criticize all the support for instance Alabama is receiving (more than Greece – or Africa I’m sure) every year. It is kind of wrong isn’t it? Greece has huge problems and moral issues etc, agreed. But I’m sure you agree that most of the aid is wasted in Alabama too.

What is the best way to deal with the issues. You said “you treat this as a technical problem”. But that’s not good enough – this is very much a political question. Technical solutions works well with machines but not with sovereigns / people. Or Europe needs the same technicalities as US have with Alabama.

Let’s play your setup for fun: say you are married with the friend having the alcohol problems. How do we deal with it – surely cutting off all the financial support and getting the divorce! Agreed!

But the thing here is that divorce is not on the table – you need literally tectonic shifts before Greece (or Alabama) is gone. Being forced to live together would you still cut the support and start scolding your friend? What are the odds you friend will get sober as told? Or is it just a big endless mess? And throw in some the geopolitics – your friend (with house keys) happens to have a nasty “friend” with attitude – better safe than sorry?

26. June 2015 at 13:37

Scott, thanks for the examples. BTW, have you tried Google site search? For example (using your first example):

http://tinyurl.com/pzd3sjk