Ha ha ha

It’s easy to ridicule economic ideas. Nathan Lewis did a Forbes piece back in 2016 that ridiculed both traditional and market monetarism. Potential Fed nominee Judy Shelton called Lewis’s article “brilliant analysis”.

Over at Econlog I defended Milton Friedman from Lewis’s attacks. At one point in an earlier Forbes post Lewis wrote the following:

Bitcoin is an entertaining little trading sardine, which might have within it some templates for use in the creation of a much better currency unit. But, to propose this for the U.S. dollar? And make it a Constitutional Amendment?

Ha ha.

Ha ha ha.

Friedman was a dope. It’s funny that decades have gone by, and practically nobody has figured this out.

I think you get the idea. It’s Forbes.

In the article Shelton praised, Nathan Lewis points to an important and not well understood flaw in NGDP targeting; inflation would move inversely to RGDP growth. (Yes, I’m being sarcastic.) Perhaps this was the part that Shelton thought was brilliant:

With a stable currency, “real” GDP might be -2.0%. However, the Federal Reserve would – automatically – increase the monetary base such that this is magically turned into an NGDP of 3.65%. In other words, the GDP deflator might be +5.65%. That would be a pretty big move for a broad, slow-moving price index like the GDP deflator. It would probably require a substantial decline in dollar value, on the foreign exchange market for example.

Yup, that’s what happens under NGDP targeting, indeed that’s the whole point of NGDP targeting. The idea is to allow real shocks to change real GDP, but not magnify the effect unnecessarily by having NGDP change as well, causing lots of unnecessary unemployment. So what’s wrong with the idea? Lewis doesn’t say. He seems to think the fact that inflation would fluctuate is an argument, even though he’s later downright contemptuous of inflation targeting. Indeed he favors a gold standard, which is a regime that would also allow the inflation to fluctuate, in this case in response to changes in the supply and demand for gold. In the end, Lewis doesn’t even present any arguments against the claim that NGDP stability is better than price stability, he simply denies it.

Lewis continues:

Then, there’s the possibility that the “NGDP futures market” could be manipulated by large financial interests. Sumner assures us that this is impossible, because some other academics wrote a paper.

I’ll come back to this later, but first let’s have some fun with Lewis’s preferred policy, the gold standard:

The gold standard has an awesome track record of real-life success over a period of centuries. That’s why conservatives traditionally supported it.

So we are supposed to attach our money to a commodity that has wild swings in price like gold? Ha ha ha.

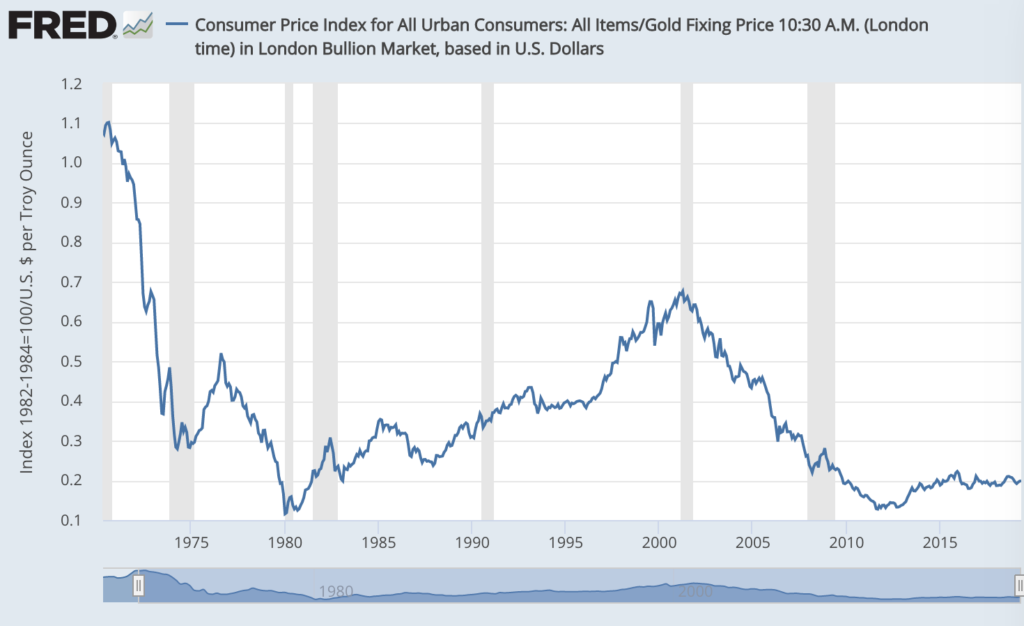

This graph shows the ratio of the CPI to gold prices, which is the price of goods in gold terms:

The deflations of the 1970s and the early 2000s are huge. Now in fairness the rise in gold’s value in the 1970s was mostly due to its use as an inflation hedge under fiat money. But the 2000s surge in the value of gold was more likely due to enormous growth in demand in developing countries, a real problem if you are using gold as money.

Lewis might argue that the US returning to gold would miraculously stabilize its value. Why, because some academics wrote a paper?

Ha ha ha.

In fact, to have any chance of stabilizing the value of gold it’s not enough for one country to adopt it as its standard, you’d need to recreate an international gold standard. So future Fed chair Judy Shelton will talk Mario Draghi and Xi Jinping into adopting the gold standard?

Ha ha ha.

Then’s there’s the great deflation of 1929-33, which directly led to the worst depression ever and resulted in the Nazi’s taking power in Germany. Is this part of the “centuries” of real life success?

I know, that interwar gold standard was not “done correctly”; the government messed it up. So let me get this straight. We need a gold standard because the government will mess up fiat money. Under gold, the government will be disciplined, prevented from creating too much money. And then when the gold standard doesn’t work because the government was too disciplined, created too little money, it’s not the fault of the gold standard?

Ha ha ha.

Some will argue that the interwar gold standard wasn’t the real thing, and that only the pre-1914 “classical” gold standard counts. But Lewis goes the other direction, even the pathetically weak post-WWII regime counts as a gold standard in his book:

Stable Money advocates still favor a gold-standard system – the proven method that served as the foundation for prosperity in the U.S. and around the world for nearly two centuries before being abandoned, after two wonderfully prosperous decades, in 1971.

Wait. The inflationary monetary policy under LBJ and Nixon was an example of the success of the gold standard?

Ha ha ha.

Lewis doesn’t seem to realize that even the quasi-gold standard of the post-WWII era was entirely abandoned in March 1968, when market price of gold was no longer pegged at $35/oz. Yes, the official price peg at $35/oz continued until 1971, but that’s meaningless. Indeed last time I looked the official price was still $42.22/oz. So by Lewis’s logic we are still on the “gold standard”.

Ha ha ha.

In fact, while there was a very weak gold standard up until 1968, the gold standard of 1929-33 was far more orthodox, albeit not as orthodox as before 1914. So if Lewis is going to claim the “gold standard” somehow created the post-WWII boom, he’s got to also own the Great Contraction of 1929-33.

Ha ha ha.

My point is not that there aren’t respectable academics advocating a gold standard. But those who do so certainly aren’t advocating the “gold standard” in effect until 1968, much less 1971. Rather they favor a highly decentralized regime where free banks would create private banknotes that are backed by gold. Bretton Woods was a government run system, and the Great Inflation began while it was still in effect.

And why isn’t Lewis worried that “market manipulation” will disrupt the gold market just as he thinks it would disrupt the NGDP futures market? I know, it’s pretty far fetched to believe that someone could manipulate the global market for important precious metal. Oh wait . . .

Silver Thursday: How Two Wealthy Traders Cornered The Market

Ha ha ha!

Now let’s go back to Lewis’s worry about market manipulation under an NGDP targeting regime. Market manipulation only make sense if you are going to extract profits from someone. But at who’s expense will NGDP market manipulators profit from? Not the Fed; I’ve advocated that they avoid taking a net long or short position. Not taxpayers. Not my 93-year old mom, she won’t trade the contracts. So are we to believe that a bunch of Wall Street firms will extract big profits from “manipulating” the NGDP futures market (or other markets in side bets) at the expense of other big Wall Street firms who passively sit back and get taken advantage of?

I actually hope someone manipulates the NGDP market. Then I can get rich taking the opposite bet. After all, market NGDP manipulation requires taking unprofitable bets in one market (NGDP futures) to earn gains in side bets in another. So let’s play!

Seriously, I know I won’t win this argument, which is why I now favor using NGDP contracts as merely a “guardrail”, where the Fed could ignore any attempts at market manipulation. I don’t think this is needed. My original plan would work fine, as no trader could do enough market manipulation to materially impact the path of NGDP. But a guardrails approach is a reasonable compromise if it will reassure people frightened of markets, people like Lewis.

HT: Sam Bell

Tags:

28. June 2019 at 09:19

Where do they find the people who think that the prosperity of the 1950-70s was due to the foundation provided by the gold standard???

The high rates of growth in those decades were due to rapid technological progress. It’s quite a common misconception.

28. June 2019 at 09:41

Iskander, You said:

“Where do they find the people who think that the prosperity of the 1950-70s was due to the foundation provided by the gold standard???”

But they were correlated. . . . 🙂

Heh, why is my smiley face not working?

28. June 2019 at 09:44

This morning I wrote a piece that shows how the dynamic As/Ad model explains all that went on over the last 25 yrs, and how, by looking at the unemployment rate to “control” inflation, the Fed has done a lot of harm.

http://ngdp-advisers.com/2019/06/28/the-dynamic-as-ad-model-is-a-good-guide-to-understanding-the-economy-over-the-last-25-years-of-low-stable-inflation/

28. June 2019 at 11:04

Ha ha ha

Great post.

28. June 2019 at 11:08

Thanks for the laugh.

Also, this is an excellent sentence:

“The idea is to allow real shocks to change real GDP, but not magnify the effect unnecessarily by having NGDP change as well, causing lots of unnecessary unemployment.”

28. June 2019 at 13:24

Of course, Lewis does not have the expertise of Scott.

He also seems to be arrogant and insolent. Friedman a dope? What is he thinking?

But what about his points, if one looks at them benevolently?

How much would the value of the dollar fluctuate after the reform? Much more than now? Could that be a problem for the global economy and for other countries?

And what about his story about Friedman and Volcker. What really happened back then? Does he have a point there as well, if you look at it benevolently or does he make things up?

I don’t know if “Ha ha ha”-posts can convince the other side. Let’s not go down on their level, because down there, they will beat us with experience.

28. June 2019 at 15:11

Sumner, don’t get on Twitter; it’s bad (I say this as a regular).

Re: China, the Uyghur problem was much more severe than the problem of Muslim terrorism in America.

28. June 2019 at 15:25

Silver has a longer history as a monetary metal and gold. In fact, in China today banks are still called silver houses.

For much of history, gold was regarded as a vulgar metal, used for brothel gilding, women’s jewelry, and the finery of insincere fops.

I propose we switch to a silver standard.

Or a tin standard—after all, by which metal do we make our tinfoil hats?

The Temple of Macroeconomics has many a totem, fable, and hagiography.

In the confusing cacophony of the chanting acolytes, which sacred text to follow?

Why not an electrum standard?

28. June 2019 at 17:02

Milton Friedman suggested that the mix of silver standard, gold standard, and dual standard countries was possibly more stable than having almost all the major countries on the gold standard. I think he is correct: it certainly lasted a lot longer.

The notion that all of monetary history somehow peaked in 1873-1913 and it’s been downhill ever since does not make much sense. Historically, silver was a much more important monetary metal than gold, and silver-dominated eras lasted centuries longer than “the” gold standard. Even if one just sticks to coins, Eurasia was essentially on the silver standard from around 500BC (the beginning of the Athenian tetradrachma) to the crisis of the C3rd, where every major Eurasian state except Rome collapsed (a crisis which was predominantly driven by the collapse of Roman silver production knocking a key prop out of the Roman-Han trading system).

The Eurasian-come-global trading system was on the silver standard (based after 1497 primarily on Spanish silver dollars/pieces of eight/peso) from the development of vacuum pumps and lead-silver smelting process in the mid C15th and then the discovery of the Potosi silver mountain until the collapse of the Spanish Empire in the Americas in the 1820s and subsequent failure of coins minted in the former empire to retain their silver content consistency (which the Spanish crown had managed to essentially maintain from 1497 until the 1820s).

If you want to go with historically proven resilience, the silver standard makes more sense than the gold standard. It was true that medieval rulers were more likely to debase their silver coins (used internally) than their gold coins (used more for international trade) but states where the branding value of consistent silver content was sufficiently high could manage such consistency for centuries.

And, while history does not repeat, it does rhyme. China exported lots of goods in return for American minted Spanish coins from the early 1500s to the 1820s (which is why Spain conquered the Philippines–to get a base close to China, possibly about a third of American mined silver went to China). Now China exports lots of goods in return for lots of printed portraits of American presidents.

BTW the suggestion that the Chinese “disdained” Western goods is mostly just silly. China produced about a third of world output but much less of its silver and used silver bullion as its main medium of account. The European economies were (by comparison) “flooded” with mined-in-the-Americas silver. Of course goods flowed to where they were exchanged for more silver and silver flowed to where it was exchanged for more goods. Having even the occasional esteemed economic historian (I am looking at you Douglass North) repeat this economically illiterate canard is sad.

29. June 2019 at 03:36

Lorenzo from Oz,

The same mistake about silver flows and “disdaining” western goods is repeated in almost every book on Indian economic history as well as when looking at China.

Often the continual silver inflow is then said to have had a large positive effect on the Chinese economy which also strikes me as wrong (due to monetary neutrality). I think Von Glahn suggests this in his Economic history of China (which is otherwise quite good).

29. June 2019 at 06:15

I agree with the post except for the last part about NGDP futures and guardrails. In theory, a trader could trade in an illiquid NGDP futures market to goad the Fed to buying or selling Treasuries. Even worse, a large trader could just be wrong about NGDP futures. In the real-world, such wrong trades don’t have money switch suddenly between markets to counteract them.

I am not completely against some sort of market guidance, but mechanical OMOs based on NGDP futures levels is too frightening. NGDP guardrails are also frightening, especially the low guardrail since the low guardrail directly reduces the monetary base.

I would instead have NGDP-linked Treasuries similar to TIPS. Treasuries have a very deep market, unlike NGDP futures which would only be traded among people betting on NGDP. The Fed could take the spreads under advisement, similar to TIPS and stock market indices today.

29. June 2019 at 07:52

Thanks Marcus.

Lorenzo, Very interesting comment.

Matthew, I agree that the proposal you are discussing might be a bad idea, but it has nothing to do with my guardrails proposal. You might want to actually read the guardrail proposal before writing comments that are unrelated. In my proposal. the markets have infinite liquidity, and the guidance is not at all “mechanical”.

29. June 2019 at 08:34

Scott,

I tried to cut down on my words, so I summarized my views on the guardrails.

The Bretton Woods system worked directly to pin the price of gold, since it bought or sold gold directly at $35/oz. By contrast, the NGDP guardrails do not directly trade NGDP. NGDP contracts are traded.

The high guardrail will work in the right direction in the monetarist sense. It reduces the monetary base. The low guardrail also reduces the monetary base. So left alone, the low guardrail seems to create a vicious cycle. Once expected NGDP goes below low guardrail levels, money pours into low guardrail contract, reducing the monetary base, lowering NGDP growth, increasing the returns on low guardrails and inducing more money to go into low guardrails.

2-3 quarters later (Since NGDP is often revised), the low guardrail bettors would have a lot of money. Perhaps eventually the money would be spent instead of being plowed back into low guardrails. But the bettors on low guardrails were people with money to spend in the first place. So the new money has lower propensity to be spent on real consumption or investment.

The response is that the Fed would immediately do OMOs. But too many OMOs and low guardrails could be used to influence the Treasury market. The Fed’s counterparty could gain more on their Treasuries than they lose on the contract.

Maybe if T-bills were traded for low guardrail contracts instead, it might be okay. T-bills could be traded at maturity value for low guardrail contracts. Then, in extreme, the Treasury could get large negative interest for selling T-bills at auction. This system may be self-correcting.

But in the end, I don’t think any proposal which opens up the Fed/US government to unbounded losses will ever fly.

29. June 2019 at 11:02

Matthew, You are obviously completely unfamiliar with my proposal, and your discussion has absolutely no relationship to what I am proposing. Everything you say is inaccurate. Not much more I can say.

30. June 2019 at 03:34

Ms. Shelton prefers a return to the gold standard, just in case readers missed the point of Sumner’s allusion to her. Zero interest rates and the gold standard. What could go wrong?

30. June 2019 at 09:25

The only problem I’ve ever seen with the guardrail proposal is that it seems radical, and the Fed is a very conservative institution. I don’t think it really is radical, but even NGDP targeting would be a big step. Also, I doubt the Fed would adopt a plan that largely, if not entirely, made it clear that a computer could easily replace them.

It could be forced on the Fed legislatively, but it’s perhaps a plan even less likely to gain legislative support. Most people, including politicians, don’t understand markets well and all kinds of conspiracies would be assumed to be afoot, on the left and right.

NIRP is more likely to be adopted, even with the political problems it also poses, and/or perhaps targeting NGDP data transmitted daily to the Fed, perhaps as part of electronic payment reform. I suspect these approaches would accompany attempts to retire paper dollars.

Unfortunately, many, many people have very negative opinions about liquid asset markets. One of the most common conversations I used to have with clients asba stockbroker was about their options applications. I would explain that to get approved to use certain options strategies, they had to state that their goal was to speculate. Virtually no one wants to consider themselves a speculator, though every action we take in life, including in the investing realm, is speculation.

1. July 2019 at 06:01

Michael, I’ve always seen this as part of a long process. Markets will gradually play an increasing role in monetary policy, one step at a time.