In philosophy the “god of the gaps” hypothesis suggests that while science can explain most phenomena, certain seemingly inexplicable events (the origin of life, the universe, the laws of nature, Morgan’s comments, etc) must be attributed to a deity. In this recent post, I argued Keynesians were using a similar argument for fiscal stimulus.

By the 1990s, most macroeconomists attributed changes in the expected level of nominal spending to monetary policy, and this made fiscal stabilization policy redundant, a sort of 5th wheel. During the recent crisis, some Keynesians have attempted to revive the arguments for fiscal stimulus, arguing that monetary policy was ineffective at the zero rate bound. When a group of quasi-monetarists reminded them that there are all sorts of unconventional monetary policy tools, the Keynesians argued that these tools would only be effective if credible, and it was unlikely that markets would believe central bank promises to inflate. Then the quasi-monetarists showed that markets did react to rumors of QE2 in a way that implied the policy was credible. Once again, Keynesian fiscal stimulus would seem to have no role to play.

Keynesian were not going to give up easily. The next argument was that while monetary stimulus can be effective, central banks were afraid to aggressively pursue this sort of policy. In that case a “gap” would open up between the central bank’s forecast of NGDP, and their implicit target. Fiscal policy can fill that gap. In essence, they argue that fiscal policy is useful in direct proportion to the degree to which monetary policy is incompetent (in the Svenssonian sense of failing to equate the policy forecast and policy goal.) And to give credit where credit it is due, monetary policy has been strikingly incompetent over the past 30 months.

[As an aside, this explains why back in 2009 both the right and left thought the other side was returning to the dark ages. The right recalled that Keynesian fiscal stimulus had been expunged from graduate education for nearly 30 years, as the fiscal multiplier is zero under an inflation targeting regime. The left couldn’t understand why the right denied that fiscal stimulus could be effective in a world where the central banks had obviously allowed inflation to fall below target.]

Before addressing some questions by Ryan Avent, I’d like to tell a brief story that might help explain why I think Keynesians are putting too much weight on the “gaps” argument. Not that the argument is wrong, but rather that it is much less right than it seems at first glance.

Years ago I used to get into arguments with our dean, who insisted that the marginal cost of admitting an extra student to Bentley was essentially zero. He relied on the common sense notion that most classes had at least a few empty seats, and hence one extra student could be squeezed in at virtually no additional cost. Here’s why I think that argument is wrong. Bentley caps classes at 35. For simplicity, assume it costs $35,000 in salary and benefits for each professor-taught course. (I.e. profs earn $140,000 in total comp., and teach 4 sections.) For each student added by Bentley, there is a 1/35 chance that the admission will trigger the need for an extra section. In that sense the dean was right. It’s quite likely that the marginal cost would be zero. On the other hand, if an extra class was needed the cost would be $35,000. Since we have no idea when and where students will trigger an extra section being offered, the expected cost of an extra student is (1/35)*$35,000, which equals $1000. And that’s also the average cost. There’s no “expected gap” to be filled, even if there are occasionally some actual gaps that can be filled at no cost.

The Keynesian gap argument is not as weak, because we may be able to observes gaps in the aggregate economy more easily than in class size. But I still think they are making an analogous mistake. For instance, let’s go back to the argument (which I agree with) that the Fed has recently allowed the forecast NGDP growth rate to fall below their policy goal. For simplicity, assume the Fed’s goal is 6% NGDP growth during the recovery, and the forecast is 4.5%. So there is a 1.5% gap that might be filled by fiscal stimulus. And furthermore (so the Keynesians argue) if fiscal stimulus does try to fill this gap, the Fed won’t take affirmative steps to neutralize the stimulus.

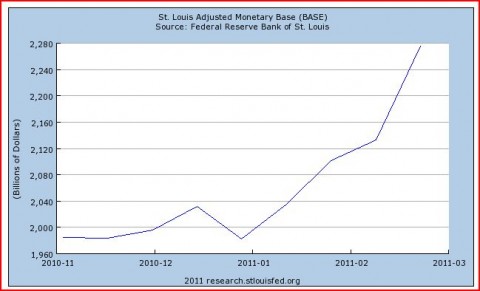

Now let’s ask why the Fed allows this 1.5% growth gap. Perhaps it is fear that unconventional stimulus is a dangerous weapon, and that we might overshoot to high inflation. (Recall the monetary base has more than doubled.) The next question is; how should we interpret that caution? Does that mean the Fed has a de facto 4.5% NGDP target? When I talk to Keynesians, I get the feeling that they differentiate between situations where the Fed is “doing nothing” and where the Fed is “doing something.” Thus the Fed would not do unconventional stimulus to push NGDP growth above 4.5%, but if fiscal stimulus pushes it above 4.5% (but below 6%) the Fed would not pull back to slow the economy. They will allow faster growth, but they won’t try to cause faster growth.

This is where I begin to part company with the Keynesians. I believe it’s better to think in terms of the Fed always “doing something.” This is probably easier to explain with an example. During the spring of 2010 NGDP growth slowed, perhaps due to dollar hoarding following the Greek/euro crisis. Keynesians argued for more fiscal stimulus, and made the quite plausible assumption that the Fed would not try to offset the effects of fiscal stimulus. One particularly sophisticated argument was that Bernanke didn’t have enough support (at that time) to push for more stimulus, but that the inflation hawks also lacked enough power to tighten policy after a fiscal boost. Monetary policy was adrift in the gap.

How do things look today? If the Keynesians had gotten their way in the spring and early summer of 2010, then Congress would have debated a new fiscal stimulus for a few months, and passed it during the second half of 2010. Would this have boosted NGDP growth in 2011? I’m skeptical, as it turns out that the monetary policy “gap” wasn’t that big. The Fed did move aggressively in November, and indeed moved in September, if you recall that expectations of monetary stimulus are the same thing as actual monetary stimulus, even in the new Keynesian model. If Congress had done another $400 billion stimulus, it seems unlikely that the Fed would have moved until they had a chance to see whether the fiscal boost would do the trick. In that case the argument for a positive fiscal multiplier is essentially that fiscal stimulus is more powerful than monetary stimulus. But in the famous cases where fiscal and monetary stimulus worked in opposite directions (1968-69 and 1981-82), monetary stimulus seemed much stronger.

Here’s my point. In the spring of 2010 even I had trouble coming up with persuasive arguments against the Keynesian proposals for fiscal stimulus. Even I had to admit that it was unlikely that the Fed would try to sabotage fiscal stimulus when the recovery was so weak. But as things played out in reality, it seems unlikely that a fiscal boost would have helped all that much, not because it would have been intentionally sabotaged, but because it would have taken the Fed off the hook, allowing them to do nothing in the fall of 2010.

It’s a mistake to think the Fed is ever really in a situation of “doing nothing.” We’ve seen them do several mid-course corrections (March 2009 and November 2010) when the recovery was unacceptably weak. During early 2010 policy was de facto contractionary, as lots of Fed officials talked about “exit strategies.” If, as seems plausible, these back and forth swings of monetary policy are reactions to expected NGDP growth, then it would be more accurate to say that there is no significant policy gap, but rather the Fed is (for whatever reason) targeting NGDP at a lower level than they would if they could rely on their tried and tested fed funds targeting approach. They are like that 85 year old lady driving her Camry very slowing, with one foot on the brake, because she read scary news reports of “sudden acceleration” problems in Toyotas. If Morgan Warstler gets right on her tail with his big SUV, and starts honking, she’ll get even more nervous and drive even slower. (Sorry Morgan, I’m using you as a symbol of fiscal stimulus.)

In this comment section, Andy Harless presented one of the best arguments for fiscal stimulus:

I still believe the “god of the gaps” argument. (In fact, I may be the only one who has made the argument explicitly. Krugman and others kind of dance around it but don’t quite come out and say it.) Moreover, I believe that we are seeing it in action, although it will never be possible to prove counterfactuals about what Fed would have done. But we saw the tax compromise last year, and we saw that forecasters revised their forecasts as a result and that subsequent economic reports were consistent with that increased optimism, and a lot of people thought that the Fed would cut QE2 short because of the improvement. But subsequent Fedspeak makes it clear that such a cutting short is highly unlikely. I’d say that we are in a gap and that Almighty Fiscal Policy is filling part of it.

I’m not going to argue Andy is wrong, rather I’ll argue he is less right than he thinks. First, Tyler Cowen often notes that the Fed is normally the “last mover” in the stabilization game. Congress acts infrequently, whereas the Fed meets every 6 weeks. In the case Andy discusses, Congress became the last mover for a variety of unusual reasons:

1. QE2 occurred around election day. This was partly because the recovery had stalled, and partly because Bernanke was waiting for more support (from the new Obama appointees) on the Board of Governors.

2. The GOP made huge gains, necessitating a compromise to prevent a huge tax increase in 2011. Obama was forced to give in on tax cuts for the rich, and in exchange was able to secure more fiscal stimulus via a payroll tax cut.

3. Because the fiscal stimulus happened to occur right after QE2, and because the Fed likes to “wait and see” after a dramatic policy shift, we can be reasonably sure the Fed won’t immediately negate the tax cuts.

I would also agree that the fiscal stimulus has been somewhat effective. But the reasons I’d give are a bit different from those of the Keynesians. I believe cuts in MTRs boost the supply-side of the economy, which slightly raises the Walrasian equilibrium real interest rate. This effectively makes monetary policy (even at the zero bound) slightly more expansionary. I don’t believe spending increases have any supply-side boost, and I think their effect on the Walrasian real rate is smaller. Hence part of the higher expected growth is a direct supply-side effect, part is the indirect effect on monetary policy, and perhaps another part is that if we exit the liquidity trap more quickly, the Fed will be more comfortable with slightly higher NGDP growth, as they can then use conventional tools. No more 85 year-old lady driving the economy.

And if Keynesians insist on defining “monetary policy” as changes in interest rates, then the tax cuts probably did lead to tighter money. Woodford argued the Fed should promise to hold rates at zero for an extended period. But the fiscal boost seems to have moved the expected date of Fed rate increases closer to the present. Unlike Woodford, I don’t necessarily see that as bad news, as it also indicates that markets think the economy will recover more quickly. So I’m not going to argue against this particular fiscal stimulus. All I’ll say is that there was a bit of luck (avoiding the usual last mover problem) and that it was effective partly for supply-side reasons. (I won’t even attempt to defend that argument here, as it’s already an over-long post.)

This post was motivated by a Ryan Avent post, which asked me to respond to three arguments for fiscal stimulus. I’ve responded to his second argument. Here’s his third:

Finally, American government debt is extremely cheap during some severe recessions (like this one), and useful as a monetary tool. Resources and labour are also quite cheap during a downturn and slow recovery. If we’re anxious to minimise the cost of public investments, there seems to me to be a strong case for building a public investment project pipeline that can be accelerated during periods of economic weakness. Save the taxpayers money by borrowing and hiring when the demand for loans and labour is low.

I agree with this argument. Projects such as infrastructure should meet a cost/benefit test. Because real rates are lower during recessions, more infrastructure will pass that test during recessions. But this isn’t how American states behave. California spends money like a drunken sailor when the capital gains revenues pour in from Silicon Valley, and everything gets put on hold when the bubble collapses. (BTW, for all you leftists who think the housing bubble shows capitalism doesn’t work, note that our governments are just as irrationally exuberant.) Yes, I’d love to see our fiscal regime become more like Singapore, but it would be far easier to reform our monetary regime to make fiscal stimulus superfluous, then it would be to reform our dysfunctional fiscal regime. I agree with Ryan’s logic; I just don’t see it happening.

If the states don’t save money in the good years, they have nothing to spend in the bad years. At this point fiscal advocates call on the deus ex machina of federal spending. But the federal government’s not good at quickly implementing shovel-ready projects; in our system that’s mostly done at the state level. Plausible federal projects, like high speed rail, are far from being shovel-ready. (There was a proposal to build high speed rail from Madison to Milwaukee, now cancelled. Having grown up in Madison I can assure you no one would have used that high speed rail service. Normal people do the very easy 75 minute trip by car, and poor people take Badger Bus, much cheaper than high speed rail.)

Ryan Avent also argued:

Mr Sumner suggests that the Fed controls the glide path, such that any fiscal boost will be offset by monetary policy and will therefore have a multiplier of zero. I don’t quite agree, for a few reasons. First, sometimes the Fed messes up, as it did in 2008. If Congress had passed a massive, immediate stimulus measure to go along with TARP, I believe Mr Sumner would agree that it would have done some good. He would prefer the Fed not to mess up, but given that the Fed will sometimes mess up, strong automatic stabilisers strike me as a very nice thing to have.

The honest answer is I don’t know, but here’s a few reasons I am skeptical:

1. Fiscal stimulus is slow. It wouldn’t prevent the initial slump, and the actual date of passage (early 2009) is about as fast as thing happen in the US. But by that time it was obvious monetary policy had also failed. The Fed knew it was behind the curve. So Avent’s argument is that fiscal authorities were willing to act more aggressively than monetary authorities in early 2009. The argument is (presumably), that a bigger fiscal stimulus bill would not have led the Fed to forgo QE1 in March 2009. Maybe. The argument is that no stimulus bill would not have forced Bernanke to pull out the nuclear option, level targeting, which is likely to be highly effective. Maybe. The argument is that the actual fiscal stimulus produced benefits in the form of faster recovery, which outweighed its costs (a big future deadweight burden on the economy, through higher taxes.) Maybe.

2. Given all this uncertainty, I can’t argue Avent is definitely wrong. If I had my way the fiscal stimulus would have involved the elimination of the employer share of payroll taxes in 2009. That’s effectively a 7.65% wage cut that doesn’t affect worker-take-home pay at all. It essentially neutralizes the negative impact of falling NGDP combined with sticky wages. Then I’d tell the Fed to get its act together and make sure it had enough monetary expansion in place to take over in 2010, once the taxes went back to normal. I seem to recall that Singapore and also a few European countries do this sort of thing.

3. I hope people reading this post will understand why even if I am wrong, we’ve got to stop building models of fiscal stimulus that rely on ever more epicycle-type arguments, and just get on with implementing a simple monetary regime of targeting the &%$@#%$ nominal GDP forecast, level targeting.

PS. Readers who skip my comment sections can sample Morgan here at 2/10, 7:07am and 2/10, 13:23pm. If only I could combine Morgan’s Hunter S. Thompson-like gonzo style with my knowledge of macro, I could be the Krugman of right-wing blogging.