Paul Krugman on fiscal and monetary policy

Here’s a puzzling passage from a recent Paul Krugman post:

One question I’ve been asked a lot is why I spent 2009 campaigning for fiscal expansion rather than monetary expansion. Well, at the Keynes conference this morning Mike Woodford gave an overview of policy options when you’re up against the zero lower bound that in some ways expressed better than I’ve managed to what I was thinking at the time.

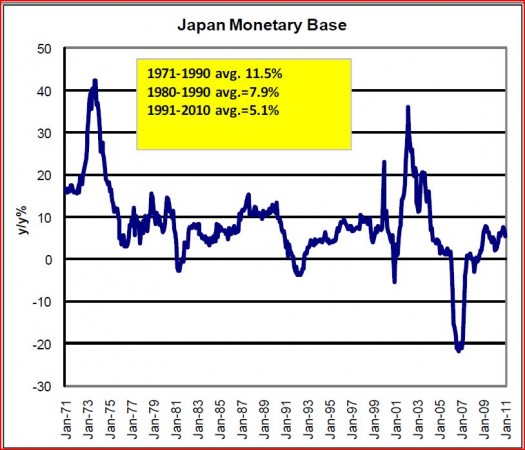

First, Mike argued that monetary expansion once you’re at the ZLB mainly works, if it does, through affecting expectations. If people don’t perceive the expansion as representing a change in policy that will persist even after the economy has recovered, even big changes in the monetary base have hardly any effect. Mike had a chart of Japan 2000-2008 that I’ve crudely reproduced:

Note both that Japan reversed much of the initial expansion in the monetary base, confirming the expectations of those who might have regarded that expansion as temporary – and Japan did this even though deflation continued! Note also that nominal GDP never moved at all despite the huge amount of money “printed”.

Krugman and Woodford are both extremely smart guys, so I can’t understand why they continue to misinterpret this graph. The Bank of Japan clearly wants to avoid inflation. That’s why they sharply tightened monetary policy in 2006 “even though deflation continued!” Indeed that’s the only plausible explanation for this tightening. But Krugman and Woodford continue to insist that this shows the impotence of monetary stimulus, i.e. the difficulty of changing expectations. They continue to assume that the BOJ was trying to inflate, but failed.

In fact, this shows that expectations in Japan were rational. The public correctly predicted what the BOJ would do. The problem isn’t convincing that public that the BOJ wants to inflate; the real problem is convincing the BOJ that they should try to inflate. Krugman and Woodford are confusing cause and effect. They see low interest rates as inhibiting monetary stimulus, whereas the low interest rates are actually a consequence of tight money, of central banks aiming too low. It’s not that the BOJ and Fed don’t know how to raise NGDP growth, it’s that they don’t want to. Don’t believe me? Then read any recent Fed statement explaining why they decided against continuing QE2.

In 2009 Krugman was too pessimistic about monetary stimulus, and thus focused on fiscal stimulus:

That’s about what I was thinking in, say, January 2009. With the severe financial crisis still relatively recent, and many people still expecting a V-shaped recovery, it didn’t seem possible to persuade the Fed to commit to a permanent rise in the monetary base or a rise in the medium-run inflation target, nor did it seem possible to convince markets that there had been a long-run change in policy. The chances for persuading Congress to agree to a large temporary fiscal stimulus seemed much better.

Back in 1998 Krugman knew better than to rely on fiscal stimulus. From It’s Baaack:

If temporary fiscal stimulus does not jolt the economy out of its doldrums on a sustained basis, however, then a recovery strategy based on fiscal expansion would have to continue the stimulus over an extended period of time. The question then becomes how much stimulus is needed, for how long – and whether the consequences of that stimulus for government debt are acceptable.

. . .

The political point is that Japan – like, we might note, the United States during the New Deal – appears to have great difficulty working up its political nerve for a fiscal package anywhere close to what would be required to close the output gap. Exactly why is an interesting question, beyond this paper’s scope.

Does this mean that fiscal policy should be ignored as part of the policy mix? Surely not. On the general Brainard principle – when uncertain about the right model, throw a bit of everything at the problem – one would want to apply fiscal stimulus. (Even I wouldn’t trust myself enough to go for a purely “Krugman” solution). However, it seems unlikely that a mainly fiscal solution will be enough.

That was quite prophetic. Fiscal stimulus in the US was woefully inadequate. The US political establishment did find the consequences for government debt to be unacceptable. And I love the quotation about a “purely ‘Krugman’ solution.” That would be one that relied solely on monetary stimulus. By August 2010 Paul Krugman had attached a different name to the money-only approach:

And I don’t understand at all [Koo’s] argument that monetary expansion is positively harmful. He seems to be making up arguments on the fly here; he’s so determined to defend the primacy of fiscal policy that he has to insist that anything else is a very bad thing. (In that sense, I guess, he’s the anti-Scott Sumner).

So now it’s the “purely Sumner solution.”

In the 1990s Krugman assumed that monetary policy steered the nominal economy, and criticized protectionists who thought Asian exporters stole jobs from the US. He had lots of great arguments. If he’s done with them, I’m happy to use his discarded ideas.