Why Japan’s QE didn’t “work”

Michael Darda sent me some interesting information about the Japanese monetary base:

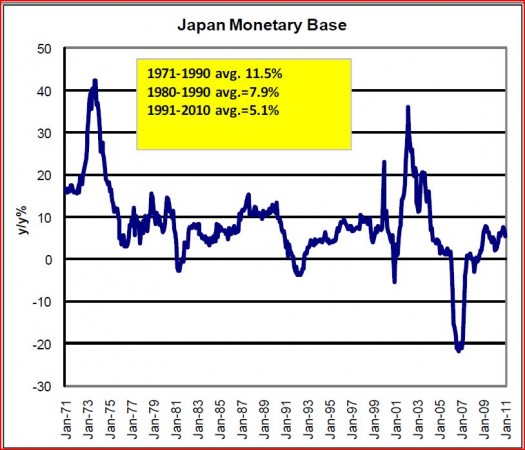

There are several ways of looking at this data. The growth in the base over the past 20 years has been much slower than during the previous 20 years. Thus it would be hard to claim QE didn’t work in Japan, as they didn’t even increase the base half as fast as when they weren’t doing QE.

On the other hand during the past 18 years Japan’s NGDP has been relatively flat. So the growth rate of the base was much higher than NGDP, suggesting a falling rate of base velocity. That does make QE look ineffective. Especially when you consider that there were brief periods when base growth soared to nearly 40%.

But an even closer look as the data shows that these spurts in base growth were temporary, and were partially rescinded just a few years later. Note the QE in the late 1990s when deflation first became a major problem. Then the small drop in the base just a year or two later. There was an even bigger bout of QE in the 2002-03 recession, followed by a much bigger drop in the base after the economy picked up a bit. This doesn’t show that QE doesn’t work; it shows that temporary monetary injections don’t have much impact on NGDP. But we already knew that, in fact it’s rather obvious if you think about it.

How do I know that the base declines in 2000 and 2006 were not just random? How do I know the BOJ was intentional tightening policy? Because on both occasions the BOJ raised interest rates, which is something no central bank does in a liquidity trap. Ever.

Some people look at these facts and see a central bank that was powerless to boost NGDP. That seems crazy to me. Why would a central bank trying to raise NGDP reduce the monetary base? Why would they raise rates? Here’s an alternative view. Suppose the BOJ was trying to prevent inflation. Then every time the CPI inflation rate rose up to zero, they would tighten policy. If my hypothesis is correct, then what type of path would one predict for the Japanese monetary base? The answer is surprising; almost exactly the path that we actually observed. Here’s why:

1. Because the trend rate of inflation fell sharply between 1970-90 and 1991-2010, nominal interest rates fell close to zero (the Fisher effect.) This would produce a large increase in the real demand for base money, or a large fall in velocity. And that’s exactly what we observed in Japan after 1990.

2. When near the zero bound, the demand for base money will not be stable. When conditions are depressed, the demand for money will pick up somewhat, and the BOJ will have to inject large amounts of base money to prevent severe deflation. That’s the late 1990s, and 2002-03. When things pick up a bit the demand for money will fall, and the BOJ will have to remove a significant amount of base money to prevent inflation. And that’s what happened in 2000 and 2006.

3. But they won’t remove all the base money injected earlier. Recall that at near zero interest rates there is that permanent increase in the demand for liquidity.

Bennett McCallum once proposed that the Fed adjust the monetary base to offset changes in velocity during the previous quarter. That would keep NGDP relatively stable. I seem to recall McCallum proposed that NGDP be allowed to grow at a modest but steady rate. The Japanese seem to have basically adopted this policy, but with a zero percent NGDP growth target. No, I don’t believe they are consciously behaving this way, but it is interesting to consider that this is almost exactly the way the BOJ should behave if it wanted to keep NGDP constant, or the NGDP deflator falling at about 1% per year.

So QE did work in Japan. They got steady NGDP. The next question is why they acted as if they had such a peculiar policy target. Some people tell me that “Japan” likes low inflation because they have lots of old people on fixed incomes. But “Japan” isn’t a person, it’s a country. Japan didn’t decide to follow a policy of stable NGDP, the BOJ did. At the very same time the BOJ was deflating the economy the Japanese fiscal authorities were aggressively trying to boost NGDP through expensive construction projects, which have put Japan deeply in debt. The BOJ sabotaged those efforts. No, “Japan” did not adopt a stable NGDP target (or mild deflation target), the BOJ did. That’s even more peculiar.

PS. I will try to catch up on comments this weekend.

PPS. I just added an interesting Romer quotation to the end of the previous post.

Tags:

25. March 2011 at 10:32

Excellent, excellent, excellent post by Scott Sumner.

Those of supporters of QE and NGDP targeting must refer constantly to Japan. Additionally, point out that asset values have fallen by 75 percent in japan in the last 20 years.

You want your property or stocks to be worth 75 percent less, in exchange for having minor deflation? Wages have sunk too. You like perma-gloom?

The long-term tight money policy is a bad policy. Look at Japan.

I cant’ say enough good things about this post, or enough bad things about having unrealistically low inflationary targets.

25. March 2011 at 10:58

And just in case anyone still thinks Japan wants more inflation…

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-03-24/boj-s-shirakawa-wrangles-with-lawmakers-seeking-bond-purchases-after-quake.html

“Shirakawa (governor of the BOJ) repeatedly attempted to quash direct buying of government debt… The policy would undermine confidence in the yen and provoke a surge in consumer prices, he said at parliamentary fiscal and finance committee hearings.”

There you have it.

25. March 2011 at 11:18

Thanks Cameron,

I was about to post the same thing. Here’s the WSJ quote:

http://online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20110324-702995.html

By Megumi Fujikawa

Of DOW JONES NEWSWIRES

TOKYO (Dow Jones)–Bank of Japan Gov. Masaaki Shirakawa repeated Thursday his reluctance to underwrite Japanese government bonds to fund post-quake reconstruction, saying such an action could hurt market trust in the Japanese currency…

25. March 2011 at 11:22

Hummm “OLd People”… Poor japanese older people, when they eventualy will have to pay extra taxes to cover a 200%/GDP debt…

Do you know why Portugal´s PM Socrates has fallen? Because he could not pass an increase of taxes to pensioners…

Deflation, even moderate, seems good for fixed nominal income; at the end, it is horrible for everybody.

25. March 2011 at 11:26

When lecturing on Japan’s Lost Decade last fall I basically made the following case to my students:

1) During 1993-2002 RGDP growth averaged 0.9%, unemployment rose almost consistently every year from 2.2% in 1992 to 5.4% in 2002. CPI fell from 2.5% in 1992 to -0.7% in 2002.

2) The Japanese announced their plan of ryÅteki kin’yÅ« kanwa (QE) on March 19, 2001 and maintained it through March 9, 2006.

3) RGDP growth averaged 2.1% during 2003-2007. Unemployment fell every year until it reached 3.9% in 2007. Deflation slowed down to -0.4% by 2007.

Now, I ask you, did QE work or was this merely a coincidence?

25. March 2011 at 12:27

Luis, finally we are getting the ball down the field! Poor people paying taxes too.

The next question becomes: How do you take care of old people who stop working at 70 and live to be 100?

Further Benji, the only way to justify blowing up savings for growth – is if we have made damn certain there aren’t any public employee sponges barnacled on the side of the ship.

Monetary policy can have only one function in such a case, to float the economy – it can’t be asked to float the government too, or politically, it will not happen.

Which leads again to very direct threats from the Fed, “if you want more QE, slash spending!!!”

25. March 2011 at 14:11

Morgan:

Euthanasia.

Seriously, past 80 we have to wonder if the quality of life justifies huge healthcare outlays. I say no–either pya out of your own pocket, or pass on. The time for living is when you are young.

25. March 2011 at 14:56

Benjamin C: but you can punish the young for taking the opportunities you didn’t by going on as long as possible …

25. March 2011 at 15:07

Could we please keep the weird drama from Yglesias’ comment section from spilling over here? I actually like reading the comments on this blog.

25. March 2011 at 15:52

Lorenzo-

Jeez, Lorenzo, I missed opportunities galore when I was young, and still do–but when my time comes, I want to go fast. If ever I can’t wipe my own butt, I want out.

BTW, have you noticed the age spread in Japan (in the general footage from Japan following the tsunami)? It looks like a giant old-age development. I understand it is getting even older. Sure, some of this is cultural–but you have to wonder if 20 years of perma-recession has already damped young people’s confidence.

25. March 2011 at 17:17

Thanks Benjamin.

Cameron. I love that quotation. I wish everyone would read that over and over again, and as doing so keep thinking “Paul Krugman says the BOJ really wants to create some inflation, but just doesn’t know how.”

Steve, Yes, I think that says it all.

Luis, Exactly.

Mark, Many people ask me how monetary disequilibrium could have lasted 18 years in Japan. As you note it didn’t. It appeared in the mid 1990s, the early 2000s and after 2008. The problem with the low trend rate of inflation is that even if wages can eventually adjust, the BOJ has no room to cut rates when there is a negative shock.

Morgan, Exactly, more monetary stimulus less fiscal stimulus.

Alex. I hope so.

25. March 2011 at 17:25

[…] by Scott Sumner(25. March 2011)  // スコット・サムナーã®ãƒ–ãƒã‚°ã‹ã‚‰ã€Why Japan’s QE didn’t “work” (March 25th, 2011) を翻訳紹介。 ã•ã£ããコメ欄㧠Excellent, excellent, excellent […]

25. March 2011 at 18:04

Benji, that of course makes the most sense… instead of raising the retirement age, we simply cut off certain kinds of care at 82, then 85, etc.

Getting the country there may actually be politically easier – but I think we’re going to raise the age once first.

This is a back door into my own analysis: we have haves and we have have-nots, and the vast majority of “pretty good” medicine is cheap enough to give out to the have-nots. It’s the modern expensive stuff – the marginal improvement stuff, the haves will never be willing to share.

But the left HATES this idea… since they aren’t commandeering all the care, and then dishing out as they see fit.

And when I used to say this exact pitch at another liberal blog – where Papola and I met – the older liberals would freak out. Putting old people on ice flows and what not.

——

Ok, Scott:

If the DeKrugman admits that Ben WILL step up if there is a slow down.

If DeKrugman admits Ben CAN successfully step up if there is a slow down.

And even, as you have said before:

Ben did not step up as forcefully when he saw Fiscal being deployed.

Then I think it follows that IN THE AGGREGATE (I can’t believe I just said that), that DeKrugman is being dishonest when he argues fear of a slow down as why not to big cuts in US Spending.

I think his entire reasoning is based on not wanting to see Public Employee Unions weakened, and Dems major funding source dry up.

I think it has nothing to do with macro… I think it has nothing to do with economics.

Is there something I’m missing?

25. March 2011 at 18:06

Alex, you can’t blame Matty for the kind of audience his work gathers, can you?

25. March 2011 at 19:25

Scott.Bernanke´s “Induced paralysis” paper is from 1999 (not 2002).

But how can things progress at the Fed if Plosser (voting member) is a previous “top gun” at the Shadow FOMC and gave the keynote speech at their meeting today, with this “biutiful” intro:

“It is a pleasure to be here today with my old colleagues and friends. I spent the better part of 15 years as a member of the Shadow Open Market Committee and served as its co-chair with Anna Schwartz for part of that time. It was a valuable experience and I learned a great deal from our discussions and debates concerning policy.

When I accepted the position with the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia in 2006, some of my colleagues thought that I had gone over to the dark side. I preferred to think of it as trying to help put the lessons of modern macroeconomics and monetary theory to work in the making of policy. That has turned out to be easier said than done for a number of reasons, not the least of which is the onset of the greatest financial crisis since the Great Depression. Some might think, based on temporal ordering or a test of Granger causality, that it was my arrival at the Fed that actually caused the crisis. Yet, we should be cautious in drawing conclusions about causation from such evidence. Personally, I prefer to think the crisis occurred despite my arrival at the Fed. But that is a story for another day…”

25. March 2011 at 19:35

“When I accepted the position with the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia in 2006, some of my colleagues thought that I had gone over to the dark side.”

As I have mentioned at this blog before I personally met Plosser in 2007. The hairs on my neck stuck up in his presence. He is evil incarnate. Only someone who is plugged into monetary issues would understand what I am saying. He is the *dark side*.

25. March 2011 at 19:48

The yield curve turned negative the month before Plosser became the Philly Fed President and remained so for a year afterward. Coincidence?

25. March 2011 at 20:32

“The problem with the low trend rate of inflation is that even if wages can eventually adjust, the BOJ has no room to cut rates when there is a negative shock.” And cutting rates is *conventional* monetary easing, and the BOJ doesn’t know how to or wants not to do anything *unconventional*. So the problem with the low trend rate of inflation is the BOJ’s ignorance or perversity; otherwise low inflation would be fine. (Right?)

25. March 2011 at 22:45

Continuing from Philo’s question, are you able to (have you tried to?) identify these nominal shocks* that the BOJ wasn’t able to handle that let their economy flounder for two decades?

*is it just nominal shocks the central bank impotence leaves them vulnerable to, or real shocks as well?

26. March 2011 at 17:18

Morgan, Who knows what people’s motives are, it’s not something that concerns me.

Marcus and Mark, That Granger causality joke may be truer than he envisions.

Philo, I think low inflation would be fine with a target the forecast regime. There is some debate about downward wage inflexibility; I’m an agnostic on that issue. A better measure than inflation is per capita NGDP growth, which you want to keep somewhat positive in my view.

Alex. The last two were the post-high tech bubble and post housing bubble periods, both of which saw very low equilibrium real interest rates. That made it hard for the BOJ to adopt expansionary monetary policy with ordinary tools. I don’t know what happened in the 1990s, presumably the after effects of the bursting of Japan’s bubble.

27. March 2011 at 14:57

[…] vou ler o Bernanke, o genial McCallum (este, todo mundo deveria ler, sempre) e, claro, este pequeno post é uma boa introdução aos problemas. LikeBe the first to like this […]

29. March 2011 at 07:46

“There is some debate about downward wage inflexibility; I’m an agnostic on that issue.” What’s the debate? So long as (expected) NGDP (per capita?) is growing at a steady rate, even severe downward wage inflexibility would cause no serious trouble.

29. March 2011 at 17:22

Philo, The debate is about whether wages are especially inflexible around 0%. There is no rational reason why workers would prefer two percent inflation and two percent nominal wage increase, to negative one percent inflation and negative one percent nominal wage increase. But many economists believe they do.

29. March 2011 at 18:54

Scott,

It’s not what economists believe that’s important, it’s how people actually behave. I think what you mean is most people are irrational about nominal quantities.

31. March 2011 at 06:47

Mark, I mean that most people are believed to be irrational by many economists. I’m agnostic on money illusion, but lean toward the view that it exists.

17. April 2011 at 09:12

Scott, have you read the book of Richard Koo on Japan http://www.amazon.com/Holy-Grail-Macroeconomics-Lessons-Recession/dp/0470823879 , it seems that there are lots of responses you are looking for in here … I would be curious to know what you think of his thesis relating balance sheet recession, nominal growth, public deficit and deleveraging, which according to him explain the low velocity of money. In his framework, the BOJ is powerless…

17. April 2011 at 10:18

BoJ isn’t powerless. They are simply terrified that they will do something that “would undermine confidence in the yen and provoke a surge in consumer prices”.

If the governor of the BoJ came down with a strange brain disorder that made him suddenly irresistibly desire to create hyperinflation in Japan, they would quickly take him into custody and lock him away for fear that he might create inflation.

17. April 2011 at 10:37

Ben, Koo is wrong. The BOJ isn’t powerless, they can devalue the yen anytime they wish to create inflation. But they don’t want inflation; they have often said they want stable prices. And indeed the BOJ is one of the most successful central banks in terms of price stability, as the CPI is almost unchanged since 1994.

Whenever the CPI showed signs of possibly rising, the BOJ tightened monetary policy (2000, 2006, etc.)

Dustin, I agree.

24. June 2011 at 14:30

I’m a bond trader, not an economist, but I found these comments very interesting, especially with regard to Japan, where I lived for 4 years. The comments regarding Japan’s outward face on economic aims being in contrast with their (monetary policy) actions got me wondering – is this some far-sighted new school of economic theory they’ve cooked up, along the lines of their famous 100 year plans? Or perhaps even more far sighted, like one of Elliot’s ‘grand superscycles’?

2. August 2011 at 20:42

“note the QE in the late 1990s when deflation first became a major problem. Then the small drop in the base just a year or two later.”

Yeah, and that’s a GOOD thing. This happened at end, not the start of the “lost decade.” Deflation should not be a dirty word. You want a tight money supply to wipe the board faster by lowering lending temporally and getting investors correctly aligned with resources and interest rates. As more businesses and people start saving, long term lenders will crop up and interest rates will fall down again. I understand a lot of people, even middle class end up loosing a lot in the short term, but it’s better than continuing in a illusion with printed money. Printed money, which by the way, ended anyway around 2000. Look at the graph at the start and end points of the 90’s.It’s lowest points are about the same. So what did all that QE do in between? They created a bubble of money so they could finally pop it and then allow the markets to recover form that condition. Why not let deflation take it’s course form the get go? Yes, taking money out leads to deflation, but that’s a good and natural process. It removes bad debts and allows for long term investment to come in, lowering rates back down over time. As for raising NGDP, that’s the end result of deflation in most case. A righted ship that sails onward if you will. I also do not see anything wrong with Government undertaking long term fiscal spending and employment measures during deflation. They know it’s coming so they set up projects that will either pnly last the duration of the deflationary period, or projects that will hopefully last beyond the deflationary stage, and be integrated into the new resulting post deflation climate. Either way, it keeps NGDP up, and people in jobs producing, even with deflation and tight lending. The Deflationary period is actually one of the best times for the Government to spend on long term investments.

“How do I know that the base declines in 2000 and 2006 were not just random? How do I know the BOJ was intentional tightening policy? Because on both occasions the BOJ raised interest rates, which is something no central bank does in a liquidity trap. Ever. ”

Look at the US today. If you raised interest rates in the US right now what would happen? Stop lending, you say? What lending? Stop investment? What investment? The entire point of a liquidity trap is that lower interest rates don’t add to lending or spending. QE just tries to inflate a way out of the trap. Which may or may not work and also takes time, not to mention uses resources in new ways that they may or may not be good at. The idea should be to steer into the spin, not out of it. If BOJ had raised rates in the first place, instead of QE, it likely would have recovered more quickly.

16. March 2012 at 07:42

[…] The reason for this is simple: Only permanent increases in the monetary base are expansionary. Since the Bank of Japan has a reputation for reversing its actions once deflation subsides, QE is accompanied with the expectation that it will later be reversed. […]

11. July 2016 at 02:38

[…] Sources: https://mises.org/library/explaining-japans-recession http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=9404 […]