Which of these statements is true:

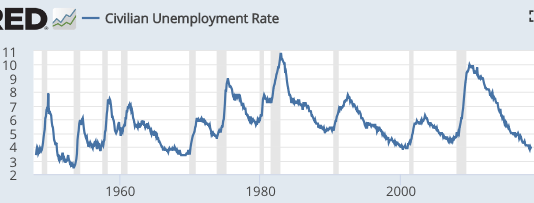

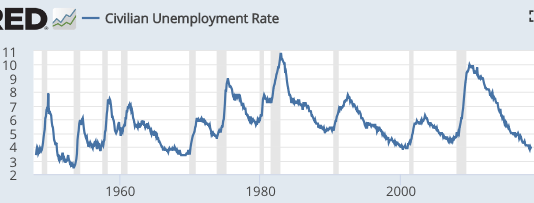

1. Tight labor markets are almost always followed by recessions within a year or two (1966 was an exception).

2. Inverted yield curves are almost always followed by recessions within a year or two (1966 was an exception.)

3. The US has never experienced an expansion lasting more than 10 years.

Actually, all three are true. And none of the three have any necessary implication for current monetary policy. (Over at Econlog, I explain why I believe labor markets are currently tight.)

Suppose we took the first statement seriously. If the labor market is getting tight, then the Fed might want to tighten monetary policy to get the labor market less tight. After all, tight labor markets are often followed by recessions. In contrast, if the yield curve inverted, then the Fed might want to loosen policy to avoid a recession. And if the expansion has lasted for 9 years, then the Fed might want to simply throw in the towel, as history tells us that there is nothing that can be done. A recession is inevitable in the near future.

In fact, history is not destiny. It’s quite possible this expansion lasts for more than 10 years. It’s quite possible that (as in 1966) a tight labor market doesn’t lead to a recession. And its quite possible that (as in 1966) an inverted yield curve is not followed by a recession. Unfortunately, we responded to the inverted yield curve of 1966 with an easy money policy, which created something even worse than a mild recession—the Great Inflation (which itself led to more severe recessions later on.)

History is no guide when the Fed is trying to achieve something that it has never achieved in all of American history—a soft landing. So why am I so naive as to think this time is different? Because Trump is President! (Just kidding.) One reason is because other countries have recently achieved soft landings. Examples include the UK in the early 2000s and of course Australia. Furthermore, the history of American monetary policy can be seen as a series of mistakes, and each time the Fed learns a lesson. The Fed no longer creates 10% deflation. They no longer create 10% inflation. Now they must learn to avoid severe recessions. I see no reason why they can’t succeed in that endeavor—Australia has already done so.

Update: Let’s define ‘soft landing’ as at least three more years of growth once the labor market has become tight.

Undoubtedly the US will still experience the occasional mild recession. But we can, should, and probably will do much better than in the past. Recall that in the 1970s, people like me who claimed the Fed could control inflation were viewed by the Very Serious People as being hopelessly naive and utopian. The VSPs are always behind the curve on monetary policy. They don’t understand monetary theory, and hence rely on “history”. But history is a very poor guide when it comes to monetary policy.

And if you insist on going with “history”, then don’t tell me what the Fed needs to do to avoid the next recession. History says a recession is inevitable, within 9 months.

Meanwhile the NGDP prediction market is up to 5.2% growth, and the number is rising. I’ll go with the prediction market over “history”.

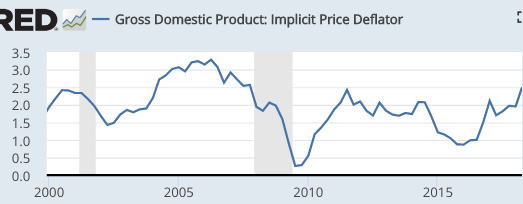

PS. I increasingly believe the Fed has (perhaps subconsciously) absorbed the most important lesson in monetary policy:

PPS. Trump in 2014:

PPS. Trump in 2014:

We need a President who isn’t a laughing stock to the entire World.

The entire world today at the UN:

Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha . . .

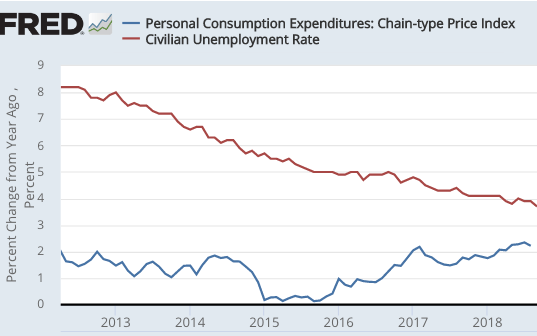

Over the previous 6 years, unemployment has fallen from 8% to 3.7%. Inflation has mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.

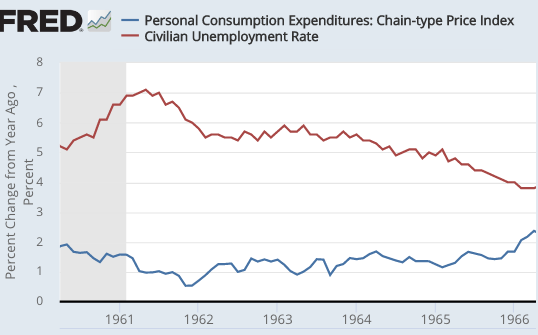

Over the previous 6 years, unemployment has fallen from 8% to 3.7%. Inflation has mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%. In this case, unemployment rose to a peak of 7% in 1961, then gradually trended down to 3.8% in mid-1966. Inflation mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.

In this case, unemployment rose to a peak of 7% in 1961, then gradually trended down to 3.8% in mid-1966. Inflation mostly stayed in the 1% to 2% range, occasionally dipping below 1%, and recently rising above 2%.