The moment of maximum danger

Some people are confused when I argue that excessive monetary ease right now could make a recession more likely. Aren’t recessions caused by tight money? Yes, but they are also caused by mistakes that lead the Fed to want to sharply slow NGDP growth. And that sort of mistake is more likely to occur when policy has previously been too expansionary.

There is an especially large risk of recession when an excessively expansionary monetary policy coincides with a peak in the real side of the economy. If inflation has been running above target at a time when real growth is robust, then there’s a danger than a slowdown in inflation will coincide with a slowdown in RGDP growth.

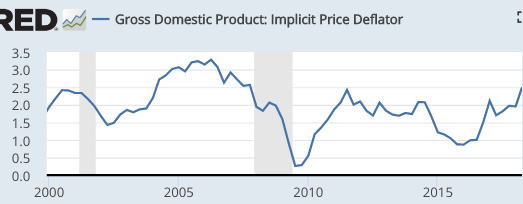

Here are a couple recent examples. In 2000-01, RGDP growth slowed due to the end of the tech boom. So why didn’t the Fed compensate with easier money, to keep NGDP growing fast enough to avoid recession? Partly because in the second half of 2000, inflation (GDP deflator) was running at 2.4%. By mid 2002 the inflation rate was down to about 1.5% (again using the GDP deflator.) Thus NGDP growth slowed even more than RGDP growth. The Fed took a real shock and turned it into an even bigger nominal shock. It would have been easier for the Fed to adopt an aggressively expansionary monetary policy in 2001 if they had not already been experiencing above target inflation in late 2000.

The same set of events played out during the housing boom. Once again, inflation rose above target. When housing slumped, it was inevitable that RGDP growth would also slow. But the Fed made things worse by causing inflation to slow even more sharply, especially in 2008-09. And the cause of their mistake is pretty clear. Because inflation had been running above target during the housing boom, they felt they had less leeway to adopt a highly expansionary monetary policy in 2008.

You can say these were mistakes by the Fed, and I’d agree. My point is that this sort of mistake is more likely to occur when NGDP growth and inflation have been excessive during the previous boom. Right now, the Fed forecasts 3.1% growth in 2018. They think this is temporary, due to factors such as the recent tax cut. They forecast growth slowing to 2% in 2020 and 1.8% in 2021. At the same time, inflation (GDP deflator) is currently running at 2.5%. It seems likely that inflation will also slow somewhat over the next couple years. Put these two claims together and it’s not hard to imagine NGDP growth slowing rather sharply by 2020. Especially if there is a “mistake”. And interest rate pegging is a regime tailor made to produce procyclical mistakes.

Under the Fed’s dual mandate, the Fed should run inflation below target during booms and above target during recessions. They have historically done the opposite, and this procyclical policy continues to this very day. Now that we are booming, inflation is finally edging above 2%. That makes a recession more likely.

I’m still not forecasting a recession, partly because I believe that recessions are unforecastable, and partly because current policy does not seem far off course. For any given one or two year period, the most likely outcome is continued growth. My point is that an excessively fast NGDP growth rate right now would make a recession in 2020 more likely, not less likely. Jay Powell has his work cut out for him.

PS. I cited the GDP deflator even though the Fed targets PCE inflation, because the GDP deflator inflation rate and the RGDP growth add up to NGDP growth.

PPS. If there is a recession in 2020, who will deserve the most blame? Perhaps those who now say, “Gee, let’s use monetary policy to see how tight a labor market we can produce.” No, let’s use monetary policy to keep NGDP growing at 4% from now until the end of time.

Tags:

27. September 2018 at 09:30

“And interest rate pegging is a regime tailor made to produce procyclical mistakes.”

I have a sense that prior to Oct 2008, the Fed at least got market feedback on its interest rate target because it had to buy or sell securities to hit its interest rate target. With IOR, it will be less conspicuous as reserves just start piling in.

27. September 2018 at 09:36

There is something I don’t understand about the Fed. If the Fed is forecasting a slowdown in real GDP growth, shouldn’t they also (most of the time) be forecasting a slowdown in inflation? I would think that slowing growth with historically be correlated with disinflation.

27. September 2018 at 09:43

Scott, great post. I’ve read your blog for years but I only now, finally, understand what you mean when you say “it’s the policy regime that needs fixing.” Not only would NGDPLT lead to better policy outcomes in recessions, but also during booms. A light bulb moment over here – and an argument for you to continue with these types of posts.

27. September 2018 at 10:08

Bill, I’m not sure how IOR will affect the cyclicality of policy.

Burgos, That’s because policy has historically been procyclical. There is nothing natural about inflation slowing when growth slows, just the opposite.

27. September 2018 at 10:09

Thanks Stoneybatter.

27. September 2018 at 10:48

I think I am beginning to see how NGDPLT isn’t procyclical. My understanding is that a real negative shock to the economy is going to drive down real growth and push up inflation. When the Fed reacts to that by pushing up rates, that causes a plunging in NGDP growth as well, which compounds the problems stemming from the real shock.

I am still a bit confused about the situation the economy is facing right now. It appears to me that inflation isn’t coming about from a negative real shock to the economy, like say a sudden reduction in the amount of oil available in the world economy. Instead, it seems that economic activity has grown to the point where there are a few bottlenecks in economic production, and more may appear if growth continues. So I guess that would constitute a kind of peak in the real side of the economy.

Since we are hitting some bottlenecks that are difficult to solve (and take time to improve), that I think would imply that economic growth should slow down a bit in the near future. I guess I am still trying to figure out what that kind of scenario implies about the path of inflation, absent Fed policy specifically designed to reach a certain NGDP level.

If we assume that NGDP keeps growing at the same rate, that would mean more inflation. However, I am not sure that the slowdown in the economy wouldn’t also lead to a slowdown in NGDP growth as well. If it is the case that a fall in the growth rate of real GDP in some way causes slower NGDP growth as well, even absent procyclical Fed policy, then I am still left in a state of confusion as to why the Fed wouldn’t forecast lower growth and lower inflation going together (though that would be a situation in which NGDP growth fell faster than real GDP growth; I don’t see why you might not get real GDP growth falling faster than NGDP growth as well).

I still feel like there is something about the dynamics of this situation that I am not grasping, and I think that it might be how changes in real GDP growth effect changes in NGDP growth. For some reason I seem to have an assumption that NGDP and real GDP growth rates move in tandem absent real shocks to the economy, such that I don’t see why the Fed should have to do much at all absent real shocks.

27. September 2018 at 10:57

Scott,

Whats your general view on how Powell would handle a recession? How would he have handled 2008 compared to Bernanke? Obviously a tough/impossible question, but just curious…

27. September 2018 at 11:23

Is it not possible that the past two recessions were due in part to phobia about inflation maybe, possibly, hitting 3% (gasp!), and perhaps that mindset is what we need to guard against? What would have happened had the Fed been less committed to slamming on the breaks at the first sign of inflation nearing 3% ahead of the last two recessions. Of course, the Fed is less anxious with inflation running below target for several years. Pretty obvious bias all century.

“It seems likely that inflation will also slow somewhat over the next couple years.” If only we weren’t at the mercy of this inflation, a phenomenon of mysterious origin.

27. September 2018 at 11:25

I mean, if growth does fall to 1.8% as you expect, don’t we need inflation to increase to maintain 4-5% NGDP growth?

27. September 2018 at 11:48

Totally agree with this article.

27. September 2018 at 12:08

Interesting.

It seems that the GDP deflator rate was high for the same reason that PCE and CPI inflation were high, relative to core inflation. Because of commodity inflation. For this reason, it has always seemed to me that NGDP targeting still carries some pro-cyclical features when there is a supply shock, though obviously not as bad as inflation targeting.

Am I right about that, or am I mistaken? Could there be value in letting NGDP growth rise to some extent when there is a commodity shock?

While I don’t like the fact that compensation is a bit of a lagging indicator, this does seem like a case in favor of your suggestion that targeting some sort of wage growth indicator would be favorable to an NGDP target.

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lnJ6

27. September 2018 at 12:13

“Partly because in the second half of 2000, inflation (GDP deflator) was running at 2.4%”.Strange, because FRED tells us that between the first quarter of 1992 and the first quarter of 2004, the GDP deflator was running BELOW 2%! Over the next 3 years it was a bit above, mostly due to the oil shock.

27. September 2018 at 12:46

Just an observation. In each of the last 3 recessions, the Fed realized before each one began that it had raised the Fed Funds Rate too high and started to lower that rate. The recessions appear to have occurred because the Fed did not lower rates as fast as the Wicksellsian neutral rate was falling, so they inadvertently kept tightening. 1995 seems to be a counter example where they responded fast enough.

27. September 2018 at 15:14

Burgos, You said:

“If it is the case that a fall in the growth rate of real GDP in some way causes slower NGDP growth as well,”

That depends on Fed policy, procyclical or countercyclical?

Jim, I don’t think he would have been as effective as Bernanke. But we’ve learned a lot since 2008, and it’s quite likely that either Bernanke or Powell would be more effective in the next recession than the Fed was in 2008.

Brian, Having a higher trend rate of inflation does not make a recession less likely. It’s all about avoiding procyclical inflation. The problem wasn’t fear of inflation, it was too much willingness to tolerate high inflation and low inflation at the wrong times.

On your second comment, the Fed is not targeting NGDP, they are targeting inflation. If they were to adopt a 4% NGDP target right now, then they’d need to tighten policy. (They would not pick 5%, given their 1.8% long run trend RGDP estimate.)

Kevin, Yes, total labor compensation would probably be better. But the Fed is currently focused on inflation, that’s why I discussed inflation in this post (as a source of error). Obviously I’d have them target something else–NGDP or labor comp.

Marcus, Again, the average level of inflation has not been a problem—it’s been around 2% since 1990. The problem is that inflation has been procyclical.

Bill, I agree.

27. September 2018 at 16:34

Meh. I am not worried about inflation. Moreover, the 2% inflation target is probably too low. Australia seems to do well with a 2% to 3% inflation band target. How did 2% become sacralized?

Let the good times roll. A couple generations of rising real wages would be the best tonic for the US economy and political outlook possible.

There is every possibility that a 2% inflation target is but a monetary noose on the neck of the economy.

Should the macroeconomics profession be characterized by a fetish for particular and low rate of inflation, or for a rate of inflation which best promotes robust economic growth?

27. September 2018 at 16:48

They wouldn’t pick 5%, but they should. 4% is a close second. If they picked 4% NGDPLT, I’d be ecstatic. And I’d buy more stocks.

27. September 2018 at 17:23

In part I am wondering what lower real GDP growth means for the Fed operationally, assuming that they want to keep nominal GDP growing at a steady rate. Do they need to lower rates to increase money supply and velocity? Pay less on interest for reserves? Maybe this is wrong, but I am thinking of a supply and demand curve for money, and wondering if the forecast for real GDP growth indicates that they will need to expand the money supply. Also, my apologies if this is Econ 101 type stuff. One thing that I am realizing is that talking about tight or loose policy is confusing, or at least more confusing than talking about supply and demand and NGDP.

27. September 2018 at 18:58

Add on:

The Reserve Bank of Australia adopted a 2% to 3% inflation-band target in the early 1990s.

The last Australian recession was in …..1991. Gee!

Despite 27 years of recession-free economic growth, inflation generally has gone down since 1991 in Australia, and now is below target, under 2%. This despite exploding housing costs, caused in some part by large capital inflows.

How 27 years without a recession? At critical periods, the RBA did not over-tighten, ala the Fed. That had that extra bit of looseness available to them, up to 3% inflation.

Maybe NGDPLT would work better than than an inflation-band target, such as Australia has. Of course, the inflation-band has a verifiable track record.

Moreover if the NGDPLT is too low, you run into the same problem as a 2% inflation target. If is just too tight, it will chronically suffocate the economy, What if meeting a 4% NGDPLT leaves trillions of dollars of cumulative lost output on the table?

With an NGDPLT, you also have a Fed that would likely “cave in” after just a couple years of no recession and no inflation.

That is, say we go into two-year in a recession with no inflation. The NGDPLT target would then call for 12-15% annual NGDPLT to get back on course.

Given the US economy can expand at 3% real or so when on a roll, this would mean the Fed, after a no-inflation recession (the modern kind), would have to target high single-digit inflation.

Of course, the Fed could never do that. They would throw in the towel, and re-set NGDPLT to a lower level.

So, any Fed NGDPLT target would be provisional—to be dropped after any modern-type recession.

Maybe we need a NGDPLT, but with a loose ceiling, or band. Call it 5+% NGDLT. Or 5% to 6% NGDPLT.

The Australian experience suggest rigidity is not the answer.

https://www.rba.gov.au/inflation/inflation-target.html

28. September 2018 at 01:56

Fresh out:

“[TOKYO] Japan’s unemployment rate fell while factory output rose for the first time in four months in August – a sign the world’s third-largest economy is on a path of gradual recovery.

The jobless rate stood at 2.4 per cent in August, down slightly from 2.5 per cent the previous month, the internal affairs ministry said.

The figure – slightly lower than market expectations of 2.5 per cent – is the first improvement in two months after the rate hit a 26-year low of 2.2 per cent in May.

The jobs-to-applicants ratio is unchanged at its highest rate in 44 years, with 163 job offers going for every 100 job hunters, separate data from the labour ministry said.”

—30—

Okay, 163 open jobs for every 100 job hunters….and inflation in Japan still far below their 2% inflation target (near 1% as I recall).

If labor market “tightness” contributes to inflation…what is up with Japan?

If something is different in Japan, could that something be mimicked in the US?

A change in tax laws, labor laws?

Still, it seems a live possibility the Fed is afraid of inflation-spooks.

28. September 2018 at 02:15

Kevin, choosing a lagging indicator to target need not be a problem at all. Just target the forecast via the futures market.

(Same reason applies to why Scott Sumner should change from suggesting targeting NGDP futures that pay out the first data to instead pay out according to fianl revision a year or so later. Paying out later is a small price to pay for more accurate data, and the financial system will allow speculators to offload the futures at very near the par of first cut of data.)

28. September 2018 at 02:20

Scott,

Taregtting labour compensation levels would definitely a better solution than NGDP for an economy like Ireland. For the US it probably wouldn’t make too much of a difference?

28. September 2018 at 08:30

Scott you wrote:

“There is an especially large risk of recession when an excessively expansionary monetary policy coincides with a peak in the real side of the economy. If inflation has been running above target at a time when real growth is robust, then there’s a danger than a slowdown in inflation will coincide with a slowdown in RGDP growth.”

I haven’t taken the opportunity over the last few years to push my dissertation, and I probably shouldn’t here. But, here I go lol…

Though Austrian capital theory is unable to explain a cycle of boom and bust alone, your story above has a very ABCT-like outcomes. I argued that Mises, Hayek, and Strigl all resorted to some measure of tighter monetary conditions as a necessary condition for turning a boom into a bust (rather than growth returning to its steady-state level, see pp. 26-28 of link below).

“Following an unexpected money supply shock, a central bank eventually confront rising inflation and unemployment as seen at t = 3. If a central bank adopts a dovish strategy to fight unemployment, it eventually creates stagflation. If it adopts a hawkish strategy to fight inflation, it creates a depression. (p. 29)”

In other words an easy monetary policy in one period leads the central bank to overcompensate with a tighter monetary policy in the next period.

This seems similar to your argument above.

https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&pid=sites&srcid=ZGVmYXVsdGRvbWFpbnxhbGV4YW5kZXJzY2hpYnVvbGF8Z3g6ZDk5MjQxOGYxZTBmNThj

28. September 2018 at 14:05

4% “for all time” is a long time. Not much time ago you said 5%.

What’s the big deal between LT labor force growth of 1% + 4% nominal compensation growth vs the 2% + 3% of yore? Or 0% + 5% in 10 years time?

29. September 2018 at 16:34

Burgos, If RGDP growth slowed, they’d likely have to lower rates to keep NGDP growth stable.

Matthias, Good points.

Alex, Yes, a procyclical monetary policy can be a problem in a wide variety of models, including Austrian.

James, I’d be happy with either 4% of 5%. I pick 4% now partly because that’s been the average since 2009, and partly because it’s probably most politically acceptable (consistent with 2% inflation, on average.) Neither of those were true when I started blogging.

30. September 2018 at 08:09

When CB have a little credit, sometimes markets recognize some integers expectation as singular (regular?) point.(6yr USD/JPY)

2. October 2018 at 16:13

Scott,

A lot of this comes down to estimates of potential. I kind of see three stories in the post crisis era:

1) The Fernald, Hall, Stock, & Watson https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/fernaldtextsp17bpea.pdf (others in this camp as well)

2) The Blanchard and Summers Story

3) And this smaller story by Gorodnichenko and Coibion https://eml.berkeley.edu/~ygorodni/CGU.pdf

I’d be interested in a post about this to hear your take. I’m a bit partial to the third story which would lead one to take a say policy is pretty neutral currently.

16. June 2020 at 06:45

Not only is Covid a disease of the aged, but WSJ claims 50k deaths occurred in “nursing homes”. It is as if we killed them on purpose. Of course we did no such thing, but everything we have done has caused worse outcomes than if we did virtually nothing—-including bad counting. Ignoring the simple actions we could take in favor of poor science creating complex actions.

Bad coding on models in Britain; an implicit desire by many to make the economy worse; the ease with which we can create panic when “science” is misapplied; the seeming complete lack of curiosity of why Asia had literally orders of magnitude less deaths than the west, the virtual elimination of deaths in A month in Western Europe based on the undemonstrative belief that shutdown was the cause.

Covid is a new disease which caused deaths which otherwise would not have occurred—-we will not know for several years how many “excess deaths” really occurred—-although it does not seem high when one accounts for the economic offset.

Our reaction to it has been a mixture of bad politics, bad science, a will by the media to believe the worst, true conflict of interest between those not immediately impacted by shutdowns versus those who were; a willingness by government to engage in an historically unprecedented action without any idea of the potentially dangerous side effects; the mockery of those who believed shutdowns were uncalled for—-etc.

The perhaps good news is that beliefs of some, like Scott, that our ability to to recover quickly is true (which may have in part helped support shutdown) —-May in fact be true—-so far it looks possible.