I’ve done recent posts on Neo-Fisherism, and the problem of identifying the stance of monetary policy. I’ve also pointed out that if we can’t identify the stance of monetary policy, we can’t identify monetary shocks.

This is going to be a highly ambitious post that tries to bring together several of my ideas, in a Grand Theory of Monetary Policy. Yes, that’s means I’m almost certainly wrong. But I hope that the ideas in this post might trigger useful insights from people who are much smarter than me and/or better able to handle macro modeling.

NeoFisherians argue that if the Fed switches to a policy of low interest rates for the foreseeable future, this will lead to lower inflation rates. Their critics claim this is not just wrong, but preposterous—and undergraduate level error. I think both sides are right, and both sides are wrong.

All of mainstream macro (including the IS-LM model) is built around the assumption of a “liquidity effect”. That is, because wages and prices are sticky in the short run, a sudden and unexpected increase in the money supply will lower short-term nominal interest rates. Interest rates must fall in the short run so that the public will be willing to hold the larger real cash balances (until the price level adjusts and the real quantity of money returns to its original equilibrium.)

One thing that makes this theory especially persuasive is that it’s not just believed by eggheads in academia. Pragmatic real world central bankers often see nominal interest rates fall when they inject new money into the economy. It’s pretty hard NOT to believe in the liquidity effect if you see it in action after you make a policy move.

So the NeoFisherians have both the eggheads and the real world practitioners against them. And yet not all is lost. Over any extended period of time the nominal interest rate does tend to track changes in trend inflation (or better yet trend NGDP.) If I had a perfect crystal ball and saw the fed funds rate rise to three percent and then level off for twenty years, I’d expect a higher inflation rate than if my crystal ball showed rates staying close to zero for the next 20 years. NeoFisherians are smart people, and they wouldn’t concoct a new theory without some good reason.

In previous posts I’ve found it useful to illustrate where NeoFisherism works with a thought experiment. I’ll repeat that, and then I’ll take that thought experiment and use it to develop a general model of monetary policy. Here’s the thought experiment:

Suppose Japan wants to raise their inflation rate to roughly 8%/year. How do they do this? This requires two steps. They need a monetary regime that produces 8% steady state trend inflation, and they need to make sure that the price level doesn’t undergo a one-time jump upwards or downwards at the point the new regime is adopted.

To get 8% trend inflation, they’d need to shift the trend nominal interest rates to a much higher level. To make things as simple as possible, suppose the US Federal Reserve targets inflation at 2%, and the BOJ has confidence that the Fed will continue to do so. In that case the BOJ can peg the yen to the dollar, and promise to depreciate it at 6%/year, or 1/2%/month. The interest parity theory (IPT) assures us that Japanese interest rates will immediately rise to a level 6% higher than US interest rates. (Note, I’m using the near perfect ex ante version of the IPT, not the much less reliable ex post version.)

We’ve already gotten a very NeoFisherian result. Currency depreciation is an expansionary monetary policy, and the IPT assures us that this particular expansionary monetary policy will also produce higher interest rates. And not just in the long run, but right away. Although Purchasing Power Parity is widely known to not hold very well in the short run, expected inflation differentials do tend to reflect the expectation than PPP will hold. So under this regime not only will Japanese nominal interest rates rise almost exactly 6% above US levels, Japanese expected inflation rates will also rise to roughly 6% above US levels.

Of course actual PPP does not hold all that well (although it does far better under fixed exchange rate regimes, or even crawling pegs like this system, than floating rates.) But that doesn’t really matter in this case; just getting 6% higher expected inflation is enough to pretty much confirm the NeoFisherian result.

Unfortunately, the immediate rise in interest rates might reduce the equilibrium price level in Japan. But even that can be prevented with a suitable one-time currency depreciation at the point the regime is adopted. How large a currency depreciation? Let the CPI futures market tell you the answer. Make your change in the initial exchange rate conditional on achieving a 1 year forward CPI that is 8% higher than the current spot CPI. Thus the CPI futures market might tell you that the yen should immediately fall to say 154.5 yen/dollar, and then depreciate 1/2% a month from that level going forward. Whatever amount of immediate currency depreciation offsets the immediate impact of higher interest rates.

Notice that monetary policy has two components, a level shift and a growth rate shift. This idea will underpin my grand theory of monetary policy. In this case the level shift was depreciating the yen from 120 yen/dollar to 154.5 yen/dollar. The growth rate shift was going to a regime where the yen is expected to gradually appreciate against the dollar, to one where it is credibly expected to depreciate at 1/2%/month.

Now think about the expected money supply path that is associated with that new policy regime for the yen. My claim is that if the BOJ simply adopted that expected money supply path, all the other variables (exchange rates, interest rates, inflation, etc.) would behave just as they did under my crawling peg proposal.

So far I’ve been supportive of the NeoFisherians, but of course I don’t really agree with them. Their fatal flaw is similar to the fatal flaw of Keynesian and Austrian macro, using the interest rate to identify the stance of monetary policy. But in some ways it’s even worse than the Keynesian/Austrian view. Those two groups correctly understand that a Fed rate cut is a signal for easier money ahead. The NeoFisherians implicitly assume the opposite.

People say that the longest journey begins with a single step. But what the NeoFisherians don’t seem to realize is that central banks generally signal an intention to go 1000 miles to the west by taking their very first step to the EAST. (Nick Rowe has much better analogies.) Thus when Paul Volcker decided that he wanted the 1980s to be a decade of much lower inflation and much lower nominal interest rates, the very first thing he did was to raise the short term interest rate by reducing the growth rate of the money supply.

As soon as you realize that central banks usually use changes in short term nominal interest rates achieved via the liquidity effect as a signaling device, then the NeoFisherian result no longer makes any sense.

But now I’m being too hard on the NeoFisherians. Look at my crawling peg for the yen thought experiment. And what about the fact that low rates for an extended period do seem associated with really low inflation, in places like Japan. That suggests there’s at least some truth to the NeoFisherian claim, and at least some problem with the Keynesian/Austrian view.

In my view the two views can only be reconciled if we stop viewing easy and tight money as points along a line, but rather as multidimensional variables:

Monetary policy stance = S(level, rate)

A change in monetary policy reflects a change in one or both of these components of the S function. You can have a rise in the price level, but no change in the trend rate of inflation. You can have a rise in the trend rate of inflation, with no change in the current (flexible price) equilibrium price level. The beauty of the thought experiment with the yen is that it makes it much easier to see this distinction. You can imagine once and for all change in the exchange rate, as when the dollar went from $20.67 an ounce to $35.00 an ounce in 1933, and then stayed there for decades. Or you can imagine a change in the trend rate of the exchange rate, as in my crawling peg example. Or you can imagine both occurring at once.

When NeoFisherians are talking about higher interest rates leading to higher inflation, they are (implicitly) changing the “rate” component of my monetary policy stance function. Keynesian and Austrians tend to (implicitly) think in terms of changes in levels, once and for all increases in the money supply that depress short-term interest rates and have relatively little effect on long-term interest rates or long run inflation.

In previous posts I’ve expressed puzzlement as to why easy money surprises lower longer-term interest rates on some occasions, and at other times they raise long-term interest rates. The “perverse” latter result occurred in January 2001, September 2007, and (in the opposite direction) December 2007.

Indeed the December 2007 FOMC meeting produced the most NeoFisherian (i.e. “rate”) shock that I have ever seen in my entire life. A smaller than expected rate cut (contractionary shock) led to a huge stock market sell-off (no surprise) but also lower bond yields for 3 months to 30 years T-securities (a big surprise.) This policy announcement had an unusually large “rate shift” component, whereas most US policy announcements are primarily “level shifts”. The markets (correctly) saw the Fed’s passivity in December 2007 as indicating that inflation and NGDP growth might be lower than normal going forward. And not just in 2008, but indefinitely.

Unfortunately, while exchange rates nicely capture the rate/level distinction, they are not ideal for developing a general monetary policy theory, as the real exchange rate is too volatile. And that brings me to the missing market, NGDP futures. If this market existed we would have all the tools required to describe the stance of monetary policy in the multidimensional way necessary to sort through this messy NeoFisherian/conventional macro debate. Suddenly we could clearly see the distinction between level shifts and rate shifts.

Unlike exchange rates, NGDP responds to monetary policy with a lag. But we could use one-year forward NGDP as a proxy for levels. Thus if one year forward NGDP rose and longer-term expected NGDP growth rates were unchanged then you’d have a level shift. If the opposite occurred, you’d have a rate shift. Or you might have both. The response of interest rates to the monetary policy shock would largely depend on the response of NGDP futures to the monetary policy shock.

In a richer model there would be more than two dimensions, indeed the expected future NGDP at each future date would tell us something distinct about the stance of monetary policy, and thus more fully characterize any monetary shocks that occurred. But I see great benefits of using the simpler two variable description, levels and growth rates. This simpler version is enough to address many of the perplexing features of monetary policy, such as why economists can’t seem to come up with a coherent metric for the stance of monetary policy, and why the NeoFisherians reach radically different conclusions than the Keynesians.

Ideally we’d create highly liquid NGDP and RGDP futures market, and then we could easily identify the stance of monetary policy, in both dimensions. This would also allow us to ascertain the impact of policy shocks on both NGDP and RGDP. NeoFisherians could say, “A monetary policy that raises expected inflation rates and/or expected NGDP growth rates will usually raise nominal interest rates.” That’s a much more sensible way of making their claim than “Raising interest rates will raise expected inflation and/or expected NGDP growth.

PS. I’ve benefited greatly from discussions with Daniel Reeves (a Bentley student), and Thomas Powers (a Harvard student). They understand NK models better than I do, and bouncing ideas off them has helped me to clarify my thinking. Needless to say they should not be blamed for any mistakes in this post.

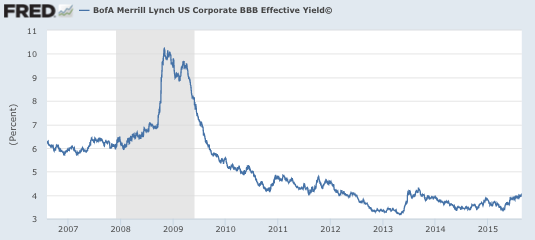

Just to be clear, real interest rates are not a good indicator of whether money is easy or tight. But the spike in BBB yields was not just a default risk story; it was also a liquidity story.

Just to be clear, real interest rates are not a good indicator of whether money is easy or tight. But the spike in BBB yields was not just a default risk story; it was also a liquidity story.