Eliminate the LM curve? Only if we also eliminate the IS curve

Over at Econlog I have a post criticizing Olivier Blanchard’s suggestions for improving the way we teach macro. Blanchard wants to focus on the IS relationship, and pretty much discard LM:

The LM relation, in its traditional formulation, is the relic of a time when central banks focused on the money supply rather than the interest rate. In that formulation, an increase in output leads to an increase in the demand for money and a mechanical increase in the interest rate. The reality is now different. Central banks think of the policy rate as their main instrument and adjust the money supply to achieve it. Thus, the LM equation must be replaced, quite simply, by the choice of the policy rate by the central bank, subject to the zero lower bound. How the central bank achieves it by adjusting the money supply should be explained but can stay in the background. This change had already taken place in the new Keynesian models; it should make its way into undergraduate texts.

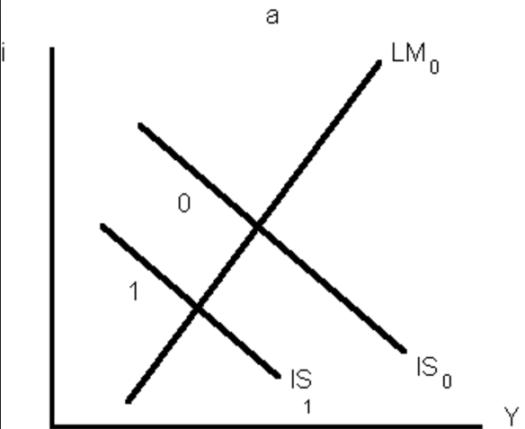

I’d rather get rid of IS/LM entirely, but if we insist on using the model, then I’d prefer we keep LM. Even with the complete IS/LM model, economists often fall into the trap of reasoning from a price change. For instance, they often assume that a fall in interest rates represents an easy money policy, even though the IS/LM model clearly suggests that it might also reflect a leftward shift in IS:

Now suppose we get rid of the LM curve, as Blanchard proposes, and instead assume that the interest rate represents monetary policy. Won’t students be even more likely to make this mistake?

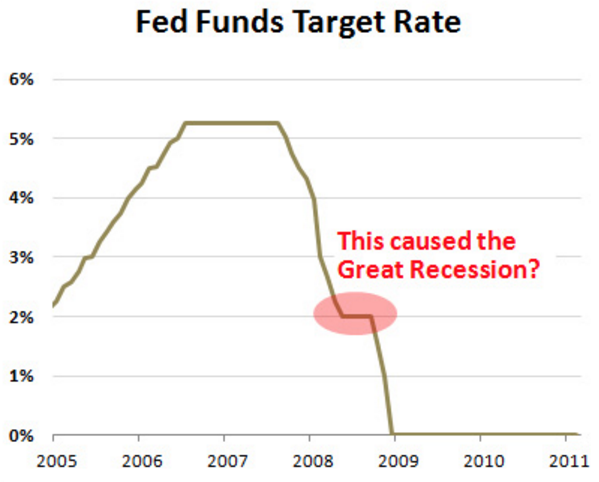

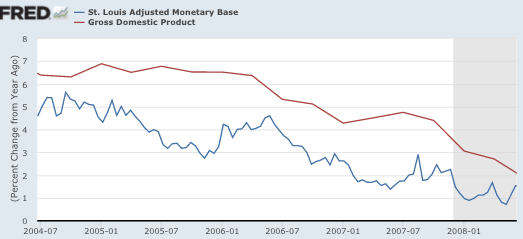

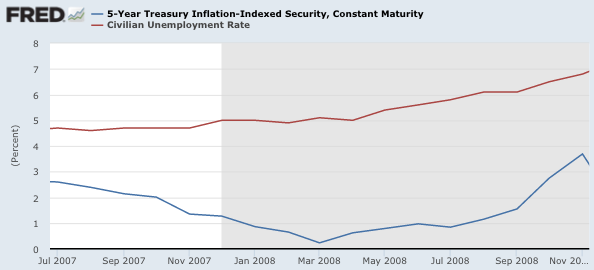

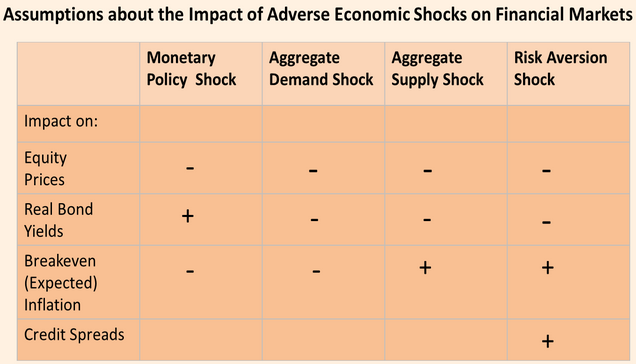

My favorite example is the period from August 2007 to May 2008, when the growth in the monetary base (which had averaged a bit over 5% in the previous decade, came to a halt. This led to a sharp slowdown in NGDP growth, triggering the recession (albeit not yet a “Great” recession.) Indeed it appears the Fed triggered the Great Recession regardless of whether you accept my NGDP view of the stance of monetary policy, or whether you prefer the old “concrete steppes” approach—was the Fed injecting new money into the economy. My worry is that people will confuse the following two graphs:

The graph on the right shows what actually occurred during the onset of the Great Recession. But if we eliminate the LM curve, as Blanchard suggests, then most students will assume the graph on the left shows what happened during late 2007 and early 2008. It will look like monetary “stimulus”. They won’t even consider the possibility that tight money might have triggered the Great Recession, as money “obviously wasn’t tight”.

What I find so maddening about all this is that we already have a macro misdiagnosis problem, and the changes proposed by Blanchard will make that problem even worse.

PS. Although I often talk about 2007-08, there are lots of other examples. Both the monetary base and nominal interest rates fell sharply in 1920-21 and again in 1929-30. In both cases money was clearly tight, as the reduction in the monetary base caused NGDP to plunge sharply. But those who focused on interest rates saw policy as being “accommodative”. If you misdiagnose the cause of the Great Depression, how likely is it that you’ll come up with effective remedies?

HT: Marcus Nunes