Expectations fairies take asset markets on a wild ride, and economists pretend not to notice

In the physical sciences, researchers identify empirical facts, and try to model them. In economics, we observe empirical facts, and then create models to explain why these facts cannot possibly actually occur. Consider:

U.S. stock futures pointed to another strong session for Wall Street on Friday, as oil prices continued to climb and investors were encouraged by signals of potential central-bank stimulus, at the end of a tough week for global markets.

Dow Jones Industrial Average futures YMH6, +1.29% leapt 210 points, or 1.3%, to 15,997, while S&P 500 futures ESH6, +1.46% jumped 27.25 points, or 1.3%, to 1,888.75. Nasdaq-100 futures NQH6, +1.86% gained 72 points, or 1.8%, to 4,202.75.

Friday was looking like a repeat of Thursday, when oil led the market higher. Then, U.S. crude prices CLH6, +5.22% rose $1.58, or 5.3%, to $31.10 a barrel, while Brent crude LCOH6, +6.36% jumped $1.88, or 6.4%, to $31.10 a barrel.

Oil and global stocks got a boost after European Central Bank President Mario Dragi dropped heavy hints on Thursday that more stimulus could be in store when the ECB meets in March. The Stoxx Europe 600 index SXXP, +3.18% was up 2.6% on Friday, while Asian markets finished with solid gains, including a nearly 6% rise for the Nikkei 225 index NIK, +5.88%

The Nikkei got a boost after an aide to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said Thursday that “conditions for additional easing have fallen into place,” according to The Wall Street Journal. The Bank of Japan will meet on Jan. 28-29, and some expect the central bank’s asset-purchasing program could be increased.

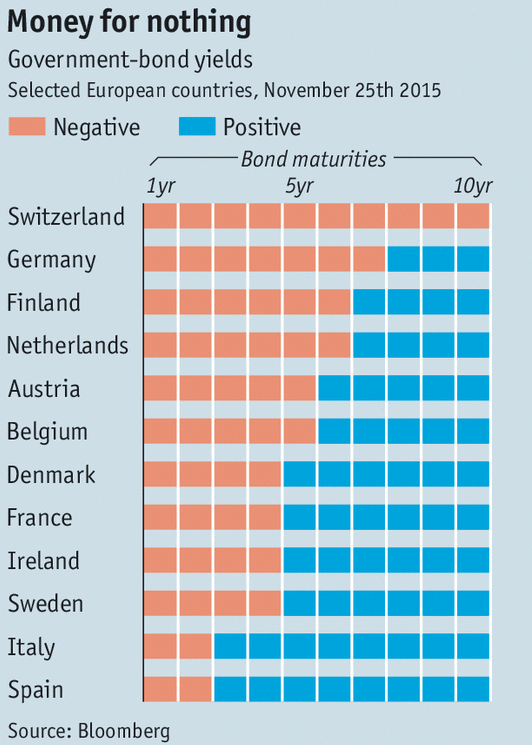

So the expectations fairies are causing wild stock and commodity price movements, even though both Japan and the eurozone are at the zero bound. And yet in the comment section I’ll have people “proving” this cannot be so, because in highly unrealistic New Keynesian DSGE models, monetary policy is totally ineffective at the zero bound.

Or they’ll say it worked, but through the expectations channel, so that “doesn’t count.” Oh really, don’t New Keynesians believe the highly expansionary monetary policy of the 1960s sharply raised NGDP growth? Isn’t that the standard NK explanation? But interest rates rose during the 1960s, so how can that be? They respond, “yes but that’s because inflation expectations rose sharply, real interest rates actually fell.” Oh, so you are saying the 1960s monetary stimulus worked by lowering real interest rates, and that only occurred because inflation expectations rose? So even when not at the zero bound, it’s all about the expectations channel? Then what makes the zero bound special?

Meanwhile Narayana Kocherlakota has a new post entitled:

It’s very short, so rather than try to excerpt it, and not do it justice, I’ll just ask you to read the whole thing. Can we all agree now that Kocherlakota was not crazy last fall, as so many people assumed? “Hey, there’s one FOMC member who wants to cut rates” “Ha ha ha”

Yeah, who got the last laugh?

Update: Update, I also recommend this blog post by Lars Svensson, another central bank dissenter who turned out to be absolutely correct.

Just imagine if Kocherlakota and Svensson were made chair and vice chair of the Fed (in either order.)

HT: Julius Probst, Marcus Nunes