We need a commission on stabilization policy

I know, you are gagging on the title of the post. I hate commissions too. But there’s already a lot of discussion about a commission to re-evaluate the Fed’s goals and tactics. And the current proposals are both too much and too little. Too much because there are some tactical questions that the Fed itself can resolve better than any commission. But there are also some questions that the Fed currently cannot answer, and where a commission could be very useful to the Fed. I believe the biggest issue now is what to do about stabilization policy in a world that frequently hits the zero bound during recessions. That’s not the world of the past 50 years, but I believe it’s quite likely to be the world of the next 50 years.

Although I don’t recall doing so, it’s quite possible that at some point in the past 6 years I insinuated that Paul Krugman favors fiscal policy because he likes big government. Perhaps there’s even a grain of truth in that statement. But there’s also one really big problem with that claim. Consider:

1. Paul Krugman strongly supports raising the inflation target to 4%

2. There is only one justification for raising the inflation target to 4%; it makes it possible for the Fed to handle 100% of the responsibility for stabilization policy.

And it’s not just Krugman; lots of other liberal economists have also favored raising the inflation target to 4%. Why do I bring this up now? Because I can just hear commenters saying how naive I am; “liberals will never agree to a plan that eliminates the need for fiscal policy.” Then why do so many favor 4% inflation target? And why does Paul Krugman say fiscal policy is pointless when nominal interest rates are positive?

Now I don’t happen to favor a 4% inflation target, and I doubt that this would be the outcome of the commission. But I do believe the commission’s output would be very useful, even if I don’t “get my way” on fiscal policy.

Both liberal and conservative economists agree on these basic facts:

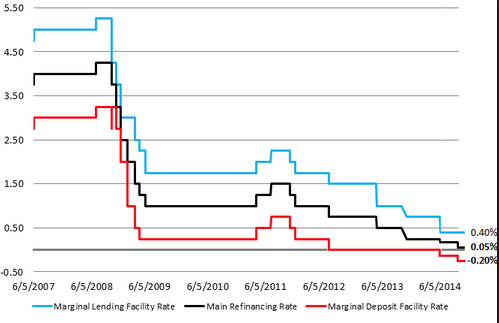

1. When trend NGDP growth rates are lower, the economy will hit the zero bound more often. One option is to raise the inflation target. The Paul Krugman solution.

2. Another option is to do something like NGDPLT. My preferred solution.

3. Another option is to keep the Fed’s current policy framework, 2% PCE inflation, growth rate targeting, and unemployment near the natural rate.

Economists also agree that option three may require some hard choices. These include:

a. Pursuing QE to the limit in a liquidity trap. Allowing the Fed to buy whatever it takes, even if they have to move beyond Treasury debt. Telling the Fed not to worry about capital risk, the Treasury has them covered. My second preference.

b. Constraining the Fed to buy securities of no more than a specific amount, say 50% of GDP, to avoid excessive risk. Other options are also possible here, such as more aggressive cuts in IOR, perhaps to negative levels. Then just live with a slow recovery. Similar to current policy.

c. Same as option b, but have an implicit agreement that once the Fed hits its QE limit, fiscal stimulus will take over. The Larry Summers solution, Krugman’s second preference.

Policy is currently hindered by the fact that the Fed doesn’t know exactly how aggressive it should be, partly because Congress is not even aware of these “hard choices.” So we don’t have any sort of clear policy regime, rather we drift in a sort of limbo, where the Fed doesn’t really know how much others want it to do. Or whether it would be scolded for large capital losses on its balance sheet if rates rose sharply. Or whether Congress would support the Fed if it shifted its target higher in order to keep interest rates above zero. The Fed knows that politicians are concerned that rates are low for savers, but doesn’t know if that concern implies they’d favor higher interest rates that are caused by higher inflation.

I don’t think this commission is politically feasible until January 2017, but at that time it just might work. I’m assuming the Dems will again win the presidency and the GOP will retain the House. Gridlock will make fiscal policy impossible unless an agreement can be reached. If you put sensible conservatives like Taylor, Mankiw and Hubbard on the committee, with sensible Keynesians, they are all going to understand the trade-offs I discussed above. The GOP economists can explain to GOP politicians “look, it’s inflation or socialism, take your choice. If we don’t have a bit more inflation then interest rates will fall to zero, and the Fed will keep expanding its balance sheet, bigger and bigger.” Or we’d get fiscal stimulus, another option the GOP doesn’t like. The liberal members of the commission can explain to Democrats “look, it’s better if the Fed handles stabilization policy, and fiscal resources are utilized for pressing social needs, not economic stabilization. And in any case, the GOP will never let us do the amount of fiscal stimulus we need, or they’ll insist on tax cuts that ‘starve the beast’.”

Krugman and I may not get our way. Maybe the commission will compromise on a monetary/fiscal mix, where the Fed takes the lead, but the fiscal authorities act if the Fed ‘s balance sheet hits X% of GDP. If I lose the battle I’ll stop objecting to fiscal stimulus. I’ll stop claiming the multiplier is zero. I’ll stop claiming there is monetary offset. If that’s clearly the regime, and it’s all spelled out, then so be it. At that point I’ll argue that payroll tax changes are the best form of stimulus.

But right now there is great uncertainty about who is in charge, and what is expected of the Fed. This stuff really needs to be clarified for the zero bound environment. Or at least discussed. I’ll bet the Fed would be thrilled if Congress told them exactly what their responsibilities were in terms of capital losses, instead of leaving it quite vague.

What would Congress decide in the end? One possibility is keeping the 2% inflation target, and a continual role for fiscal policy. That’s very possible. Or Congress might ask the Fed to study options for preventing the zero rate bound from hamstringing monetary policy, and they might buy into a technical fix like level targeting and/or NGDP targeting. I don’t know. But politics goes in cycles. After so many years of gridlock, 2017 might be a good time for a compromise. To make this happen we all have to starting talking up the idea right now—assuming anyone agrees with me.