Why so negative?

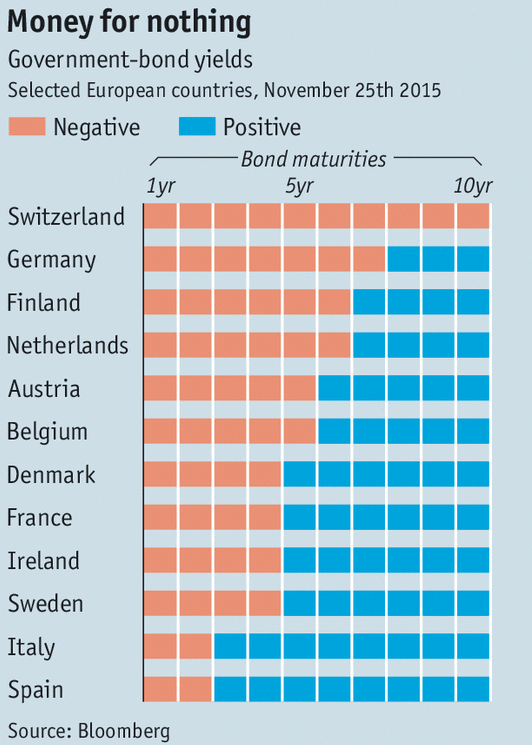

Here’s an interesting graph in The Economist, showing the extent of negative interest rates, by country and by maturity:

Not only are interest rates negative on 10-year Swiss government bonds, they are significantly negative, minus 41 basis points according to the FT. Here are some observations:

Not only are interest rates negative on 10-year Swiss government bonds, they are significantly negative, minus 41 basis points according to the FT. Here are some observations:

1. The differences within the eurozone mostly reflect default risk. But notice that despite the default risk, even Spain and Italy have lower government bond yields than the US.

2. The differences between the eurozone (especially Germany) and Switzerland relate to expected exchange rate changes. The Swiss franc is expected to gradually appreciate against the euro. Why is that? Perhaps because the Swiss National Bank (SNB) has pursued contractionary policies in the past, especially when it (foolishly) allowed the SF to sharply appreciate at the beginning of the year. Traders naturally expect more of the same. The Danes sensibly kept their currency pegged to the euro.

3. OK, but then why are eurozone rates lower than in the US? The euro has recently depreciated. Here you need to distinguish between levels and rates of change. (And this is something that lots of people miss.) An expansionary monetary policy can be thought of as reducing the value of the currency, or reducing the expected growth rate in the value over time (or both). But those are actually two radically different kinds of expansionary policy. The recent ECB policy has resulted in a one-time reduction in the value of the euro, but from this point forward it is expected to appreciate against the US dollar. Why? Probably because the ECB’s inflation target is a little lower than the Fed’s inflation target, although low eurozone rates may also be related to ECB credibility problems.

4. As far as the low level of interest rates in all developed economies, I attribute that partly to slow NGDP growth, but there also have to be other factors involved. And always remember that a low interest rate is not a monetary policy, it might reflect either easy money (liquidity effect) or tight money (NeoFisherian view.) Keynesians and NeoFisherians both make a mistake in assuming that a low interest rate policy can deliver some sort of desired result. (Oddly they make exactly opposite errors on what sort of results.) Low rates are not a policy.

5. Tyler Cowen linked to Matt Rognlie’s research papers. (Any top university not making him a job offer should have their head examined.) He has a paper on the zero bound that is full of interesting stuff. I particularly liked the analysis of the welfare costs of negative interest. Friedman showed that positive interest rates were a tax on money, and hence inefficient, but I had never given much thought to the costs of a subsidy on currency use. Rognlie also notes (correctly in my view) that before currency is withdrawn from circulation the government should first withdraw high denomination notes.

6. Although most have us have been surprised that currency demand near the zero bound is less elastic than we expected, I still think it might be more elastic in the long run than in the short run, due to the cost of adjusting currency stocks. I’d note that US currency demand seems to be moving upward with a lag, after short term rates fell close to zero in late 2008. On the other hand the negative 41 basis point yield on long-term Swiss bonds suggests that investors expect the SNB to maintain significantly negative rates for an extended period of time. So even in the long run, demand can’t be perfectly elastic at the zero bound. I recall reading that the SNB was informally discouraging currency use, by telling banks not to pay out large sums of currency to depositors. (Unfortunately I forgot where I read that.) Of course the US government has been trying to criminalize the use of significant sums of currency.

7. The Economist article has some interesting speculation on the future of currency at the zero bound:

As interest rates creep further into the red, economists’ prescriptions have become bolder. In a speech in September Andy Haldane, the chief economist of the Bank of England, outlined a range of options to allow rates to go lower still. The most radical would be to get rid of the mattress option by abolishing cash altogether. Ken Rogoff of Harvard University calculates that there is $4,000 of currency in circulation for every person in America. Much of it is used to hide transactions from tax authorities or the police. Abolishing it would curb such activities, as well as helping central bankers.

Yet depositors might still find ways to safeguard their savings. Switching to foreign currency or precious metals would be an obvious option. As Kenneth Garbade and Jamie McAndrews of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York point out, taxpayers could make advance payments to the taxman and subsequently claim them back. Depositors could withdraw funds in the form of bankers’ drafts (certified cheques) to use as a store of value. Such drafts might even become a form of parallel currency, since they are transferable. Any form of pre-paid card, such as urban-transport passes, gift vouchers or mobile-phone SIMs could double up as zero-yielding assets. If interest rates became deeply negative, it would turn business conventions upside down. Companies would seek to make payments quickly and receive them slowly. Their inventories would grow fatter.

Note that even if depositors found a way to avoid sharply negative interest rates after the abolition of currency (say by holding foreign currency, or pre-paying taxes), the central bank could still use negative rates to reduce the demand for bank reserves (make it a hot potato), and hence boost NGDP. But as always they need to be aware of where the Wicksellian rate is, and not just chase the Wicksellian rate lower in a futile attempt to jump-start NGDP growth. They need to get ahead of the curve.

BTW, I strongly oppose the abolition of cash. Like high taxes on cigarettes, it’s a highly regressive policy that seems to have support among progressives.

PS. Marcus Nunes sent me an excellent Jim Pethokoukis interview of Tino Sanandaji, discussing the Swedish economy. Lots of interesting info on Swedish history, the current immigration crisis, etc.

Tags:

30. November 2015 at 19:35

Scott, do you have any upcoming media appearances, or are there any book reviews, you can alert us to in support of the book’s release tomorrow?

30. November 2015 at 20:51

Sumner makes this statement: “An expansionary monetary policy can be thought of as reducing the value of the currency, or reducing the expected growth rate in the value over time (or both). ”

What does the ‘or’ clause mean? Sumner agrees with Major Freedom? Needs clarification, like most of Sumner’s fuzzy prose.

30. November 2015 at 22:04

differences between Italy and the US reflect the differences in the expected level of the overnight rate.

Your arbitrage is buy US treasuries earn US yields

or

Buy Italian treasuries and hedge the FX risk. The hedge has a carry equal to the difference between the local currency overnight rate.

1. December 2015 at 02:47

“”Why is that? Perhaps because the Swiss National Bank (SNB) has pursued contractionary policies in the past, especially when it (foolishly) allowed the SF to sharply appreciate at the beginning of the year. ”

I worked extremely well with way too many people out of U of C finance not to begin wondering if there is some sort of Chinese wall between the finance and econ departments.

You tell me the difference in interest rates between 2 countries with independent currencies and I will tell you every time which one is expected to depreciate in the forward markets. It ain’t magic, it’s just understanding simple arbitrage. (OK, not 100% of the time if rates are extremely close, and I don’t know the countries international financial transaction laws – but these don’t change fair value – just the bid-offer spread around fair value)

You mock Ray for at least availing himself to a finance perspective, your unwillingness to do just that makes you say things that are truly cringe worthy.. Like last week when you said countries can maintain their currencies and NGDP simultaneously, to which I pointed out any commodity producing country would have had an NGDP disaster on their hands had they not devalued.

You are sloppy, Scott. Be glad that in your world sloppiness shows up only as red on exam papers and not account statements.

Doug M… first one leaves you open to forward currency risk so is not an arb. Second one – difference in rates should be equal to the carry and therefore offset any profit. (I hate discussing arbs in Euro countries – essentially you are just closing a box and leaving yourself open with the default risk of (Euro vs chosen Euro country) as what appears as your edge in the trade.

1. December 2015 at 03:15

I look at that chart and I think two things.

The first thing is that the people who say the Fed is keeping interest rates artificially low really, really have a hard time explaining this chart. Massive conspiracy no doubt.

The second thing I think is why don’t these countries consider negative interest rates as a “free lunch” and either spend until rates come positive, or cut taxes until they do. What am I missing here?

1. December 2015 at 03:53

Today is “The Midas Paradox” Day!

1. December 2015 at 05:21

Kevin Erdmann has some very interesting data (12+ part series & growing) on why he believes low interest rates are the result of a broken mortgage market in the US. Link below, worth the read if you have time.

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2015/11/why-are-low-interest-rates-such-mystery.html

1. December 2015 at 06:30

CA, Not sure, but I’ll let you know.

Doug, You said:

“differences between Italy and the US reflect the differences in the expected level of the overnight rate.”

So differences in interest rates reflect differences in interest rates? OK, but what causes those differences?

Derivs, You said:

“You tell me the difference in interest rates between 2 countries with independent currencies and I will tell you every time which one is expected to depreciate in the forward markets. It ain’t magic, it’s just understanding simple arbitrage. (OK, not 100% of the time if rates are extremely close, and I don’t know the countries international financial transaction laws – but these don’t change fair value – just the bid-offer spread around fair value)”

Yes, I’m no dummy, I understand the interest parity condition. You seem to have overlooked that I also tried to explain what caused that discrepancy. Next time you think I’m a moron, you might at least entertain another possibility before commenting.

You said:

“Like last week when you said countries can maintain their currencies and NGDP simultaneously, to which I pointed out any commodity producing country would have had an NGDP disaster on their hands had they not devalued.”

And you accuse me of being dumb!! I never said anything like what you claim I said here. Of course many of the EMs needed to devalue to avoid falling NGDP.

Jerry, I agree with your first point. On the second, unless rates stay negative forever, debts must eventually be repaid. Consider what happened to Greece.

Simple, Yes, Kevin has done some great work.

1. December 2015 at 07:57

Cash in circulation is booming in the developed world.

For a long time the standard line was, “Well thats all drug deals.” But now we see $6000 per capita in Japan, $4000+ in the US, and rising amounts in Europe.

The emergence of large underground cash economies will play havoc with reported economic statistics.

One could also posit that a growing underground economy, untaxed, will result in higher taxes on the above ground economy… driving even more activity underground.

Thus a 0% inflation economy and negative interest rates present long-term threats of

collapsing social and tax systems, as more transactions are handled in cash.

1. December 2015 at 09:04

Rather than worry about negative nominal interest rates, it sure seems like it would be easier to get inflation back up and only have to worry about negative real interest rates instead.

1. December 2015 at 09:14

Scott, how can the euro be expected to appreciate vs the USD when they are pursuing expansionary monetary policy (I.e., expanding QE in size and tenor, more negative deposit rates, etc.)? The ecb inflation target may be lower, but that’s really irrelevant in the face to the deflationary forces the ecb is fighting. The stated inflation policy target could be zero, but when actual rates are negative 5 years out the curve, why should the market care – and thus appreciate the euro – what the stated inflation policy is?

1. December 2015 at 09:25

So differences in interest rates reflect differences in interest rates? OK, but what causes those differences?

The difference in intermediate rates is in part a result of the difference in overnight rates.

The Italian 30 note is about 2.5% or 2.75% above the overnight rate.

The US 30 year is about 3% or 2.75% above the overnight rate.

In the “belly of the curve” the US curve is steeper because the prospects for growth in the US in the short to intermediate term are greater and the Fed is expected to begin raising rates while the ECB is expected to extend QE.

1. December 2015 at 10:49

It still feels like the heart of the low interest rates is both decrease in business investments and lower housing borrowing. (I am guessing the higher rates in the US is due to more business investment especially in oil & gas markets compared to Europe.)

1) I am not sure why people think housing is bouncing back substantially any time soon. The population starting to decrease in Europe and the US has it slowest growth ever. (also the average home is probably lasting longer.)

2) One aspect of low rates is people are paying back housing loans quicker (because they are signing 15 years & simple math of the mortgage calculation). I believe since 2010 the borrowed amount on US housing is remarkably stable $13.3 – $13.5T.

3) The Great Recession pushed back the optimal age to marry to ~30 so people are not jumping into the market until 32ish. (Generation X got into houses in late 20s while older generations started purchasing houses 23 – 25.)

4) The job market has turned tight for skilled experienced employees are fine but it has yet to trickle down to less experienced workers.

1. December 2015 at 11:56

Why oh why did Tyler Cowen just link to this column???

http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-12-01/why-qe-can-t-be-the-answer-for-china

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/12/tuesday-assorted-links-41.html

I think this column on China deserves to be skewered. After skimming, the author describes symptoms of NGDP deceleration without seeing the root of the problem is NGDP deceleration.

Is that about right or should I have read more closely?

1. December 2015 at 22:41

Arnold Kling has a new post on negative interest rates on his blog entitled “I Admit I Do Not Understand a Negative Bond Interest Rate”

2. December 2015 at 01:07

Scott

Things are on the move in the Euro Area and, while Darghi remains on the front foot, we could even see prosperity.

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/12/01/good-ngdp-news-from-spain-and-even-italy/

2. December 2015 at 09:02

“Krugman makes many other points in the review, but overall he is sympathetic toward Reich’s view that growing income inequality has a lot to do with growing monopoly power in markets.”

http://marginalrevolution.com/marginalrevolution/2015/12/paul-krugman-reviews-robert-reich.html

2. December 2015 at 11:56

Scott

Bad news from and for Switzerland. Good news for robustness of Market Monetarism.

Plus some great charts on nominal wage stickiness and its consequences from a publicly available UBS presentation on their Swiss Compensation Survey 2016:

https://thefaintofheart.wordpress.com/2015/12/02/switzerland-goes-to-negative-ngdp-growth-it-wont-end-well/

2. December 2015 at 12:33

Ben, You are right, the cash economy will make it easier to evade taxes.

Randomize. Yes, but they never do things the easy way.

David, You need to look at Dornbusch’s 1975 “overshooting” model. An expansionary monetary policy produces a one time currency depreciation, to below it’s long run equilibrium, but from that point forward it is expected to appreciate (due to the interest parity condition).

Doug, Obviously I know all that, the question is what explains the future path of expected short term rates.

Travis, Yes, lots of people miss the NGDP angle. I’ll do a post on the NYROB piece by Krugman.

James, I’m glad to hear that.

2. December 2015 at 13:31

Why the Euro may appreciate?

“The competitiveness is causing a trade surplus, which is sort of the point of the policy, but what that means is that when Americans buy an Audi or a Volkswagen…they take their dollars, they give them to the dealer, the dealer gives them to Mercedes or to Volkswagen, then they sell their dollars, buy euro, meet their payroll and build their reserves, whatever they do with their money. What happens when you are running a trade surplus is the world is selling dollars to buy euro, to buy products. Selling yen to buy euro to buy products. So it puts continuous upward pressure on the euro, which in this case has been offset by massive portfolio selling. You can look at the drops in central bank holdings from near 30 percent to under 20 percent reserves in euro right now. At some point that dries up.”

http://dialogosmedia.org/?p=5829

2. December 2015 at 21:28

So I found this in an article discussing the new 5-year transportation bill. Can anyone explain this? Are they really setting Fed policies via a transportation bill?

The bill, which will go to the White House for the president’s signature this week, also lays to rest for five years the question of how to pay for transportation. The bills arrived in the conference committee with starkly different funding provisions. The committee settled primarily on a House plan to use money that the Federal Reserve Bank uses as a cushion against losses and a Senate proposal to reduce the amount of interest the Federal Reserve pays to banks.

2. December 2015 at 21:29

Sorry forgot to include the link to the article:

https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/trafficandcommuting/after-weeks-of-negotiations-congress-finalizes-5-year-transportation-bill/2015/12/01/e86f1704-979a-11e5-94f0-9eeaff906ef3_story.html

3. December 2015 at 00:50

Slightly OT: http://www.bloombergview.com/articles/2015-12-03/more-ecb-stimulus-raises-the-question-of-insanity

How can apparently intelligent people (IQ = 120?) write and publish such nonsense?

3. December 2015 at 09:33

Liberal, I haven’t followed that issue.

Jason, Even the highly intelligent often struggle with monetary policy.