Rajat left an interesting comment on my recent Australia post, with some quotes by top Australian policymakers:

Australia has a central bank (the RBA) that is reluctant to cut the cash rate further to avoid ‘financial instability’ due to (as Marcus says) asset price ‘bubbles’ ‘popping’. RBA Governor, Glenn Stevens, has called Sydney house prices ‘crazy’:http://www.sbs.com.au/news/article/2015/06/10/sydney-house-price-boom-crazy The media release accompanying every monthly RBA policy decision refers to property prices, particularly Sydney’s:http://www.rba.gov.au/media-releases/2015/mr-15-15.html

To me, it seems the RBA wants a certain type of ‘handover’from mining investment to other forms of growth. It seems comfortable with some increase in private consumption, but not too much. Stevens recently said:

“But the bigger point is that monetary policy alone can’t deliver everything we need and expecting too much from it can lead, in time, to much bigger problems. Much of the effect of monetary policy comes through the spending, borrowing and saving decisions of households. There isn’t much cause from research, or from current data, to expect a direct impact on business investment. But of all the three broad sectors – households, government and corporations – it is households that probably have the least scope to expand their balance sheets to drive spending. That’s because they already did that a decade or more ago. Their debt burden, while being well serviced and with low arrears rates, is already high. It is for this reason that I have previously noted some reservations about how much monetary policy can be expected to do to boost growth with lower and lower interest rates. It is not that monetary policy is entirely powerless, but its marginal effect may be smaller, and the associated risks greater, the lower interest rates go from already very low levels. I think everyone can see that.”

http://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2015/sp-gov-2015-06-10.html

Stevens’ RBA deputy, Phil Lowe, recently said:

“I suspect that it is unlikely to be in our national interest for this more prudent approach to give way to household consumption once again growing consistently much faster than our incomes. This is something we continue to be cognisant of in the setting of monetary policy. Some decline in the rate of household saving is probably appropriate as the economy rebalances after the terms of trade and mining investment booms. But, given the position of household balance sheets, it is unlikely to be in our long-term interest for a consumption boom to be financed by a pick-up in household borrowing.”

http://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2015/sp-dg-2015-08-12.html

However, it’s clear the RBA would love to see an increase in non-mining investment. RBA speeches frequently exhort businesses to invest in a similar manner as you once criticised Mark Carney for saying to Canadian businesses. For example, see this speech from Stevens last August:

“But the thing that is most needed now is something monetary policy can’t directly cause: more of the sort of ‘animal spirits’ needed to support an expansion of the stock of existing assets (outside the mining sector), not just a re-pricing of existing assets. There are some encouraging signs here. Nonetheless, if reports are to be believed, many businesses remain intent on sustaining a flow of dividends and returning capital to shareholders, and less focused on implementing plans for growth. Any plans for growth that might be in the top drawer remain hostage to uncertainty about the future pace of demand.”

http://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2014/sp-gov-200814.html

The RBA would also like to see an increase in exports. The Governor’s monthly statements invariably refer to the level of the dollar and until very recently (with the AUD now down to US 70 cents from $US1.05 in 2011-13), included statements that “further depreciation seems both likely and necessary”: http://www.rba.gov.au/media-releases/2015/mr-15-11.html

Finally, while statements in support of supply-side economic reform are always welcome, to me it seems this recent speech by Stevens is a bit cheeky:

“Growth is important. And for a while now, there has not been quite enough growth. There has been growth, and more than in many countries. But, recent labour market outcomes notwithstanding, not as much as we ought to be capable of. “

Followed by:

“Reasonable people get this. They also know, intuitively, that the kind of growth we want won’t be delivered just by central bank adjustments to interest rates or short-term fiscal initiatives that bring forward demand from next year, only to have to give it back then. They are looking for more sustainable sources of growth. They want to see more genuine dynamism in the economy and to feel more confidence about their own future income.”

http://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2015/sp-gov-2015-08-26.html

There’s a lot there, so let me give an overview of how I see these issues.

It’s fashionable to make wise sounding pronouncements about how monetary policy is not a panacea, and how we need a “balanced” approach, how we need to watch out for debt bubbles, and how fiscal must do its part, and how we need supply-side reforms, etc.

Unfortunately three issues get all mixed up here:

1. The need to produce a stable path for NGDP (or perhaps nominal total compensation in the case of Australia.)

2. The need for supply-side reforms to boost RGDP growth

3. The need for financial market reforms to avoid excessive indebtedness.

Let’s clear up some misconceptions. Monetary policy is a panacea for stable NGDP growth. And you need stable NGDP growth (or nominal total comp.) regardless of what else is happening in the economy. Monetary policy does not boost the economy by encouraging lending, it boosts the economy by encouraging more NGDP. Higher lending is a side effect.

If there is excessive lending (due to moral hazard, tax breaks on debt, etc.) you still do whatever it takes to keep NGDP on target, but you also have tighter regulation of lending, so that more of the NGDP growth is non-credit oriented growth (like restaurant meals) and less is credit oriented growth (like housing.)

Monetary policy is not a panacea for a lack of RGDP growth. Indeed the central bank should ignore RGDP. Instead, policymakers should try to boost RGDP with supply-side reforms.

Australia’s not even at the zero bound, there’s utterly no reason not to do austerity right now.

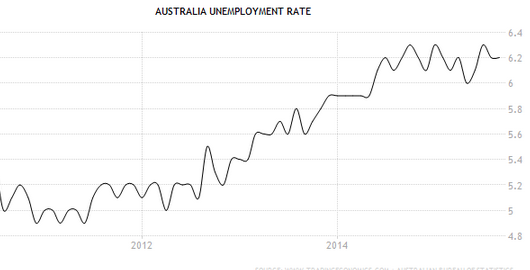

One other point about Australia. Watch the unemployment rate. RGDP in Australia is distorted by mineral exports, which are not very labor intensive. The RBA needs to keep the labor market close to equilibrium, by slow and steady growth in total labor compensation. If RGDP and even NGDP falls and yet unemployment is stable, you have a pseudo-recession, not anything for the central bank to worry about.

HT: Matt McOsker

It bounces around, but I see no significant trend. Ironically, Aussie unemployment had a mild upward trend before the commodity bust:

It bounces around, but I see no significant trend. Ironically, Aussie unemployment had a mild upward trend before the commodity bust: That was probably due to the slower than trend rate of NGDP growth.

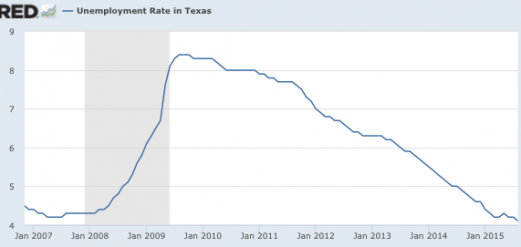

That was probably due to the slower than trend rate of NGDP growth. Notice that between February 2008 and June 2008, Texas unemployment actually rose from 4.3% to 4.7%, despite soaring oil prices. The reason? US NGDP growth was slowing sharply. Then in the second half of 2008, unemployment soared much higher, as NGDP fell (as did oil prices.) Over the past year, the unemployment rate has continued to decline, and is now at 4.1%, just above the all-time record low of 4.0% of late 2000.

Notice that between February 2008 and June 2008, Texas unemployment actually rose from 4.3% to 4.7%, despite soaring oil prices. The reason? US NGDP growth was slowing sharply. Then in the second half of 2008, unemployment soared much higher, as NGDP fell (as did oil prices.) Over the past year, the unemployment rate has continued to decline, and is now at 4.1%, just above the all-time record low of 4.0% of late 2000.