Russ Roberts has a very good interview with David Autor, one of the authors of a recent paper on the impact of Chinese imports on the US manufacturing sector. Autor actually says that China’s been a net positive, but some of the commenters I’ve read seem to have gotten the opposite impression.

I hoped that the interview would clarify things, but I’m just as confused about Autor’s argument as before. Indeed I still can’t tell whether he is making an aggregate demand argument or an aggregate supply argument. The Autor, Dorn and Hanson (ADH) paper looked at the period from 1990 to 2007, so we can immediately take the AD hypothesis right off the table. Monetary offset obviously applies, indeed the Fed did a great job during this period. So it has to be an AS problem, presumably due to the difficulty of reallocating labor from one industry to another.

Unfortunately, the points made by Autor in the interview only seem to make sense if you assume it was an AD problem. For instance, he mentions the US trade deficit:

And then the fourth factor–and this one is really, is difficult also to explain the origins. But the U.S. trade deficit is a big part of this. And the reason is–well, first of all the United States has a merchandise trade deficit as a share of share of GDP (Gross Domestic Product), as large as 3 or 4 percentage points during the 2000s. So, quite large. And a trade deficit, you can think of as, it’s like we’re borrowing. So it’s like if we were making a bunch of stuff for ourselves: we are making shoes and leather goods and furniture; and then all of a sudden China comes along and says, ‘Hey, I can make these more cheaply than you.’ And we say, ‘Okay, great. We’ll buy some.’ And they say, ‘And you know what? I’ll just lend them to you. You can pay me back later.’ And if we had had to say, if there had been a deal–and again, I’m personifying: there is not any country saying, this is not part of an explicitly crafted deal. But if there had been a situation where we would have said, ‘Okay, we are going to get those goods from you, but we are going to produce something else in exchange,’ then we would have had labor reallocating from one manufacturing activity to another, presumably. So, we say, okay, we’ll buy these furniture from you but we will sell you these electronics or these aircraft parts or something. But not doing that, it’s like we took a set of activities that we were engaged in, that employed, millions of people actually to do them, and we just stopped doing them. And instead just got the goods on loan from another country. Now, in the long run, we have to pay that back. And to pay that back, presumably we have to either make more stuff for export, which will create a lot of employment. Or we have to devalue the U.S. currency, which will lower our standards of living but will also have the effect of making those debts easier to service. But the trade deficit does loom large. Because it means in the short term, it’s like an inward shift in labor demand: stock that we were paying ourselves to make, we just got elsewhere without having to pay for them. And so that was pretty contractionary for demand for the type of workers–I’m sorry, these manufacturing labor-intensive goods that we started getting from China instead of producing domestically.

First of all, even if you think that trade deficits cause unemployment, the US trade deficit today is no bigger than 30 years ago (as a share of GDP.) So it can’t be the trade deficit causing all this unemployment during the China boom; the deficit has not increased in recent decades. So let’s go back to the reallocation problem. Maybe Autor is saying that the jobs lost to workers in some industries were not offset by growth in other industries. OK, that’s possible, but that argument would be equally true if there were no trade deficit, indeed if we had a huge trade surplus. Even if Boeing had ramped up production enough to absorb all those unemployed workers from shoe factories, the workers would probably lack the needed skills, and be living far from the available jobs. Different workers would have gotten those Boeing jobs.

But Autor then seems to suggest the reallocation problem doesn’t apply to countries like Germany, which ran a trade surplus:

And certainly the things we are talking about: what did we do with these cheap interest rates and low-cost loans? You could say that it was a squandered opportunity, right? That didn’t have to be the case. Many other countries responded to China’s rising productivity by importing Chinese goods from China but then selling China other goods. So, Germany did that. Germany runs a trade surplus with China, and most of Europe is relatively more in balance. So, the reason I bring up the trade deficit is not because there is something intrinsically wrong with trade deficits: they are an opportunity. Basically someone is lending you something or making an investment in you, and you can use that as you like. However, it did mean the manufacturing jobs that might have occurred if we were running a trade balance–workers would have been reallocated from one type of manufacturing potentially to another–that didn’t occur. So that’s part of the reason there wasn’t faster reabsorption. A second question you are asking me is: Has the U.S. labor market become less flexible, so that these shocks matter differently? Why aren’t we just getting back on our feet the way we should or the way we perceived ourselves to have done in the past?

Suppose lots of Germans lost jobs to Chinese imports. How were those made up elsewhere? Maybe they found jobs in other companies. But the contrast drawn between Germany and the US makes no sense on either theoretical or empirical grounds:

1. It’s no easier for an unemployed worker from a shoe factory to get a job in a capital goods manufacturing firm like Boeing or Intel, than it is to a get a job in construction or services. So what if the German economy saw the drop in manufacturing jobs in one sector offset by gains in another manufacturing sector? I could argue that the US economy saw the offsetting job gains in construction and services. The German trade surplus has no bearing on the question of whether there are net job losses in the US.

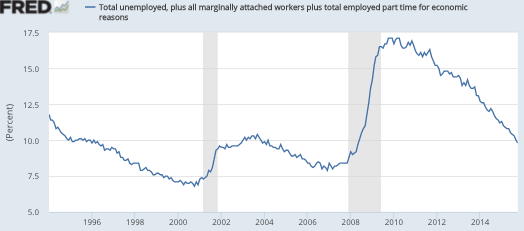

2. On empirical grounds, Germany (and Europe more generally) is a really weird point of comparison. During the period studied by ADH, the US economy did far better than Germany and Europe at job creation, and we had a much lower unemployment rate. So even if you think my theory is wrong (and it’s simply standard economic theory) the empirical evidence provides no support for the claim that Germany did a better job at reallocation of labor.

Keep in mind that ADH did a cross-sectional study. What they showed is that places like Silicon Valley did a lot better than areas concentrating on low-skilled, labor-intensive industry. But it’s not at a clear the extent to which that reflects unusually bad performance of the lagging areas, or unusually good performance of the boom areas in the US. To answer that question, ADH would have to tell us the impact on overall US employment, and that’s almost impossible, especially with their empirical methods. Thus, how would they even begin to estimate the net impact of China trade on total US employment vs. total German employment? Among other things, you’d need a monetary policy reaction function. If monetary policy offset applied (which seems almost certain) then you’d have to look for changes in the natural rate of unemployment. Most estimates suggest that the natural rate of unemployment has fallen over the past 30 years. So then the argument would have to be that China prevented the natural rate of unemployment from falling even faster. Or maybe the labor force participation rate was depressed—that did decline during 1990-2007, but only by about 0.5%

You may not think that net job changes matter, and that the ADH story is just about reallocation. But it does matter. Roughly 30 million jobs are created and destroyed each year in America. It matters a lot whether the 1.5 million jobs they believe were lost to Chinese imports were offset (as I believe) by 1.5 million new jobs created elsewhere.

Even if I am right, the China trade surely created lots of losers, as does all disruptive new technologies. Because China is so big and so fast growing, it was more disruptive than most other shocks. Yet it was still small compared to the shock of technological change, which first hit agriculture, and then later manufacturing. Yes, China may have sped up technological job loss, by switching our manufacturing to less labor intensive industries. But even if China did not exist, manufacturing employment in American would be plunging lower, decade after decade, due to technological change.

I suspect that ADH misinterpreted the implications of US trade deficits, and overestimated the disruptive impact of China’s exports. There is no question that China had major regional impacts in the US, and their study does a good job of showing this. But the discussion of trade deficits ends up garbling their message, and makes it easier for people like me to take potshots. This comment by Autor is right on the mark:

I think the thing we agree on, and really the point of our paper: it’s not about the net job losses. It’s really about the degree of concentrated loss. Right? Even if the gains are positive in all likelihood on net, it was very devastating the way that people were not expecting to specific subsets, specific regions that went from being relatively robust manufacturing centers to being rather blinded[?], or at least to a subset of people losing career employment and not being able to find good alternatives. And that’s what we’re trying to draw attention to. The other part, the calculus, which is the net gains are very likely positive. However, the distributional costs, which we’ve always known about in theory but hadn’t seen a lot in practice, we now saw that very, very clearly. And I can talk more about how we did that if that’s helpful, as well. [Emphasis added.]