When organizations have made up their mind

I suppose that most of us have experienced that sense of helplessness when our employers are determined to do something, even though it’s becoming clear that it’s the wrong move. In my field (academia) it might be a new and “innovative” MBA program, which is not well thought out. Once a lot of effort has been put into developing the program, it’s hard to stop.

This problem occurred in the space program, back in 1986:

More than 30 years ago, NASA launched seven crew members to space on the space shuttle Challenger, but they never got there.

Seventy-three seconds after lift-off, one of the shuttle’s fuel tanks failed, generating a rapid cascade of events that culminated with a fireball in the sky, eventually killing all the passengers on board.

While we all probably know this story, there’s another equally tragic account from engineer Bob Ebeling that strikes a chord with us for a different reason.

The night before the disaster, Ebeling, along with four other engineers, had tried to halt the launch, according to an exclusive interview from NPR with Ebeling.

The five engineers worked for NASA contractor Morton Thiokol, who manufactured the shuttle’s rocket boosters — the two rockets on either side of a shuttle that fired upon lift off.

They knew that this mission would involve the coldest launch in history, and that the shuttle’s rocket boosters weren’t designed to function properly under such extreme temperatures.

The night before the explosion, Ebeling said in the NPR interview, he’d told his wife: “It’s going to blow up.”

I recall reading that while NASA pretended to be bewildered by the accident, the stock market figured out the cause almost immediately, and Morton Thiokol stock plunged. Now we find out that the NASA bigwigs knew all along who was to blame, they were.

In December, Narayana Kocherlakota warned that the Fed was in danger of losing credibility, as market indicators of inflation expectations fell increasingly far below target. But the Fed had put a lot of effort into developing a “liftoff” of interest rates, and wasn’t going to be pushed off that goal by warnings that it was a mistake. Let’s hope NGDP in 2016 does better than the Challenger. If not, the Fed will pretend to be bewildered by “shocks” that mysteriously hit the economy in 2016.

The beauty of markets is that they admit mistakes within milliseconds, and reverse course when new data comes in. They have no ego. Recall Keynes’s famous comment:

When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do, Sir?

This applies to very few people and almost no organization. But it perfectly describes markets. That’s why intellectuals with minds closed to new ideas are so contemptuous of the flighty nature of market prices. “Make up your mind!” No, don’t make up your mind—keep changing it as new information comes in. Every millisecond.

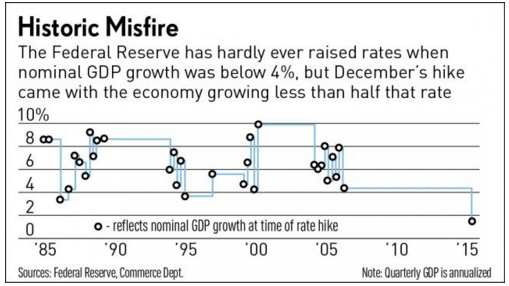

BTW, Ramesh Ponnuru sent me an interesting article by Jed Graham, showing that the Fed raising rates during a quarter of 1.5% NGDP growth was unprecedented in modern history:

If you take a four quarter perspective, the rate increase looks even more unusual. The 4 quarter NGDP growth rate came in at 2.9%, which is well below the levels of previous rate increases:

The data discussed above and displayed in the accompanying chart reflect the annualized pace of growth in each quarter the Fed hiked rates. But if one looks at the pace of GDP growth from the year-earlier quarter, the Yellen Fed stands alone as the only Fed to hike rates when nominal growth was below 3%.

Commerce Department data show the economy grew 2.9% from the fourth quarter of 2014, unadjusted for inflation. There have only been three other times that the Fed hiked when nominal year-over-year growth was less than 5%. Once was in 1986, when growth was 4.9%. The other two times came during the Volcker recession in 1982, when nominal growth fell as low as 3.2%.

While the Yellen Fed didn’t go so far as to admit a mistake, its policy statement after Wednesday’s meeting did implicitly acknowledge that policymakers were no longer confident about the path of inflation.

A footnote on the Japanese decision to adopt negative IOR. I’m told it only applies to new reserves, not existing reserves. This is similar to an idea I proposed back in April 2009, in a (ridiculously long) reply to Greg Mankiw.

Suppose the government pays 4% positive interest on required reserves and negative 4% interest on excess reserves. The penalty rate on excess reserves affects behavior at the margin, and should reduce ER holdings to the very low levels that existed before reserve and T-bill rates were nearly equalized.

Not exactly what the BOJ did, but close in spirit. Just one more crazy MM idea that people told me could never be done in the “real world”, because I’m just an academic in an ivory tower that knows nothing about finance and banking.

Check out Nick Rowe’s post on this same general issue.

PPS. I won 10 euros in the Hypermind market last year, as I shorted NGDP early in 2015, when the price was around 4.2%