“Don’t bother me with facts, my model tells me everything I need to know”

That’s a made up quote, and perhaps a bit of hyperbole. But it illustrates something that really bugs me about the blogosphere. People make all sorts of claims about monetary policy near the zero bound:

1. QE has no effect

2. Negative interest rates would be contractionary

3. Central banks cannot depreciate their currencies at the zero bound

And then when the theories are actually tested and the results are in, they keep making the same claims, seemingly oblivious to the fact that their theories have been discredited.

Today I’d like to talk about negative interest rates on reserves (IOR). There are two broad approaches to this topic. There’s what I’d call the “finance approach”, which claims negative IOR would actually be contractionary, because . . . well I’m not quite sure why. Something about how it interacts with the banking system. I used to see these articles in the Financial Times.

I tell people to ignore banking when studying monetary policy—focus on the supply and demand for the medium of account (base money). Negative IOR causes a fall in the demand for base money, and thus is expansionary. Period. End of story.

But just to make sure, let’s look at reality. The Telegraph has a nice story on negative rates on Sweden, which was the first country to adopt the policy I proposed in early 2009. (I deserve zero credit for NGDP targeting (the idea’s been around forever), but surely at least a tiny bit of credit for negative IOR.) Before getting to the Telegraph story, let’s look at how markets responded to a recent negative IOR shock:

Updated March 18, 2015 11:14 a.m. ET

STOCKHOLM””Sweden’s central bank has slashed its key policy rate deeper into negative territory and expanded its bond-buying program to prevent the recent appreciation of the Swedish krona from stifling a budding revival in inflation.

The Riksbank, the Swedish monetary authority, lowered its benchmark rate to minus 0.25% from minus 0.1% and said it would buy government bonds worth 30 billion Swedish kronor ($3.45 billion), an extension of bond purchases worth 10 billion kronor announced earlier. The repurchase rate had stood at minus 0.1% since February, the first time it was cut into negative territory.

. . .

The Swedish krona fell sharply against the euro, which gained about 1% against the krona in the minutes after the announcement, hitting a high of over 9.34 kroner. Sweden equity markets jumped to a record high with the OMX Stockholm 30 Index up 1.5% at 1,700.

Yup, cutting the IOR is expansionary, even when in negative territory. And those sorts of market responses (assuming at least partly unexpected, as some of them are) should have been it for the “finance” theories that negative IOR is contractionary, but you can never drive a stake through these zombie theories. There are still those “models” . . .

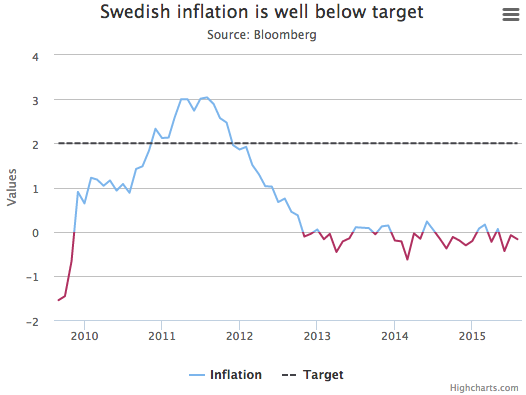

The Telegraph story looked at some macro data, which at first glance looks like a mixed bag. Inflation has been running around negative 0.1% to minus 0.2% for 4 years:

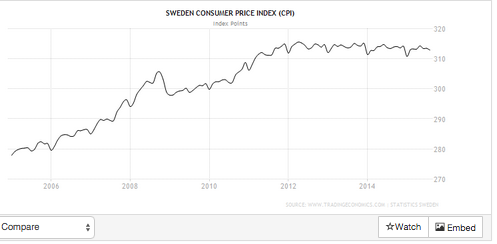

It looks like 3 years, but that’s a quirk of year over year data, the actual CPI shows it’s 4 years:

It looks like 3 years, but that’s a quirk of year over year data, the actual CPI shows it’s 4 years:

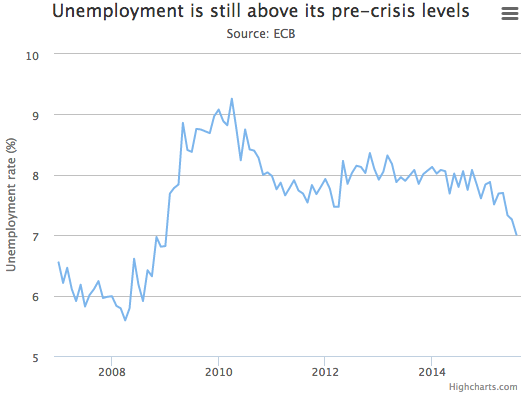

So that doesn’t look very good for negative IOR. But recall that in most countries inflation has recently been falling sharply, due to the plunge in oil prices. Inflation has never been a reliable indicator. NGDP growth has recently been accelerating in Sweden (up at a 9% annual rate in 2015, Q2), and the most recent RGDP growth shows 3.2% over the past year, which is higher than in previous years. The best evidence comes from the unemployment rate, which leveled off at 8% after the Riksbank’s disastrous monetary tightening of 2011, but has recently fallen to 7%.

So that doesn’t look very good for negative IOR. But recall that in most countries inflation has recently been falling sharply, due to the plunge in oil prices. Inflation has never been a reliable indicator. NGDP growth has recently been accelerating in Sweden (up at a 9% annual rate in 2015, Q2), and the most recent RGDP growth shows 3.2% over the past year, which is higher than in previous years. The best evidence comes from the unemployment rate, which leveled off at 8% after the Riksbank’s disastrous monetary tightening of 2011, but has recently fallen to 7%.

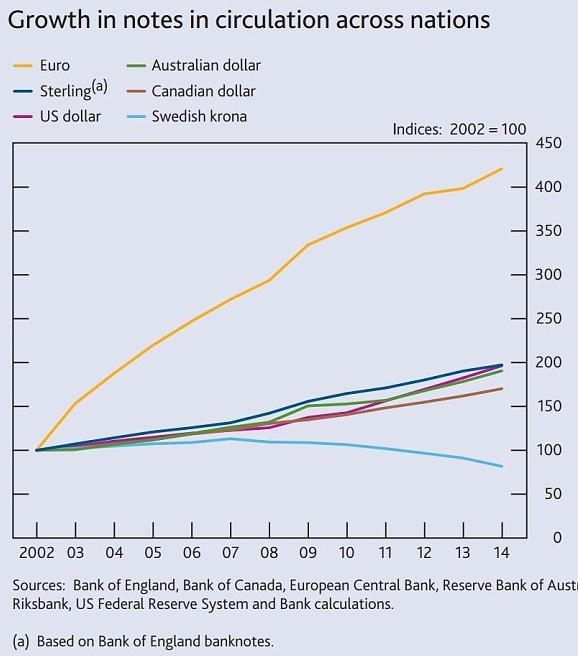

One final graph, which is really weird. While other countries are seeing a surge in currency hoarding, Sweden is experiencing exactly the opposite, despite the negative rates. What’s up in Sweden? Will the Nordic countries be the first to adopt the sort of cashless 1984-style panopticon state that is so beloved by authoritarians and Puritans everywhere?

PS. I have a reply to John Cochrane over at Econlog.