Is Fannie&Freddie spelled ‘Caja’ in Spanish?

Matt Yglesias recently made this remark in a post criticizing Tyler Cowen’s assertion that the GSEs significantly worsened the US housing/banking crisis:

The part where unwise public policies to subsidize homeownership would seem to come into this is step (1), but we in fact see this happening in many markets (Spain, commercial real estate) where Fannie and Freddie weren’t players.

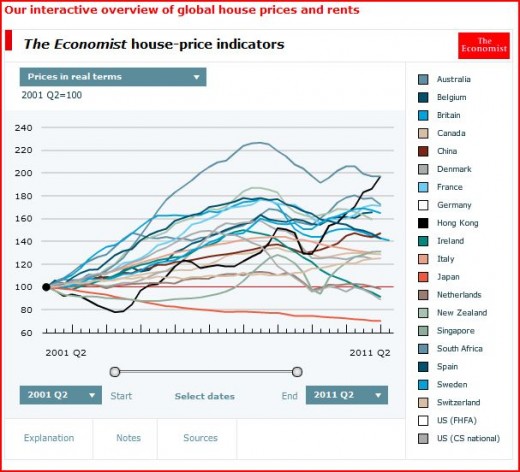

I’m not sure what Matt means by “many markets.” According to the interactive housing price graph constructed by The Economist, only the US and Ireland experienced major housing bubbles. Spain had a smaller one (although I suspect more accurate figures would show a more serious price decline in Spain.) Japan and German also saw price declines after 2006, but they had had zero price run-up before 2006–so no bubbles there. The vast majority of industrial countries saw big increases in real housing prices between 2001 and 2006, just like the US. But unlike the US, prices tended to move sideways after 2006, even in real terms. (Of course you can find some brief price dips in the severe 2008 recession, but nothing like the long collapse in the US, which pre-dated the recession.)

But let’s take a look at Spain. It’s true that Spain does not have a single institution called “Fannie Mae.” But do they have a similar problem of governments deeply involved in promoting real estate lending? I’m no expert (and I welcome critiques) but my initial impression is that the answer is yes. Here’s The Economist:

Another duality lies in the banking system. Observers fret that the Spanish state may have to pump a lot more money into the banks than the roughly €25 billion ($36 billion), or 2.5% of GDP, it currently reckons will be the total bill from Spain’s epic housing boom and bust (Ireland’s bank bail-out bill is over 40% of GDP).

The problem is concentrated in the cajas, local savings banks that make up around half the domestic banking system, rather than big Spanish banks like BBVA and Santander, which are protected by big international businesses. Not before time the government is overhauling the cajas. Their ranks are being slimmed””the number has fallen from 45 to 18″”and they are being reorganised as joint-stock companies that can raise equity capital. José Maria Roldan, director-general of banking regulation at the Bank of Spain, says that the reform is “a huge step forward, replacing the caja model with a standard banking template that is more secure and comprehensible to international investors.”

So I decided to further investigate the cajas, and this is what I found (also from The Economist):

IN THE end CajaSur trusted in God. On May 22nd the small savings bank (or caja), which is controlled by the Roman Catholic church in Córdoba, was seized by the Bank of Spain after failing to agree on a merger with Unicaja, a larger Andalusian rival. The move shocked investors and prompted other savings banks to hasten consolidation. But mergers between wobblier cajas, which are unlisted and make up close to half of Spain’s financial system by assets, are merely a first step in a longer process.

CajaSur is tiny, holding just 0.6% of Spain’s financial assets. Yet its seizure unsettled investors for two reasons. First, it was a reminder that politics often trumps rationality.

. . .

The politicians who control the cajas like this virtual structure because it allows the banks to keep their own brands, governing bodies and local retail operations while combining treasury and risk-management functions.

. . .

Encouragingly, both the government and the opposition have agreed to reform the law governing savings banks.Attracting private capital requires other changes, too, such as a reduction in the influence of politicians, something caja managers would relish. Greater openness about banks’ balance-sheets would also help: on May 26th the Bank of Spain moved in this direction by announcing plans for tougher provisioning rules.

“The politicians who control the cajas”? I thought banks were supposed to be controlled by businessmen, not politicians. I’m still no expert on Spanish banking. But I’d wager that further investigation would turn up the same incestuous relationship between politicians and the cajas that we saw between politicians and the GSEs.

So we observed clear-cut housing bubbles and busts in just two countries with more than 5 million people; the US and Spain. And both suffered from the same problem—politicized institutions that will require massive transfers from the public. Both also had large private banks that made mistakes, but at least they didn’t impose huge burdens on the taxpayers.

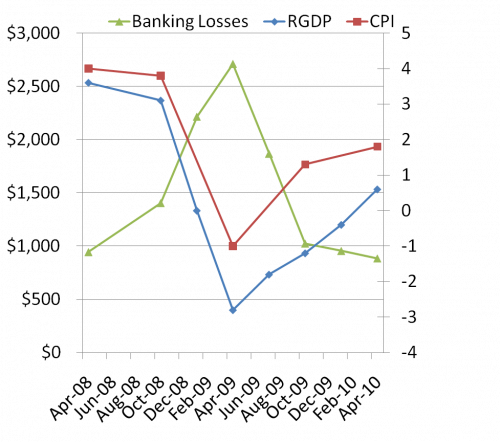

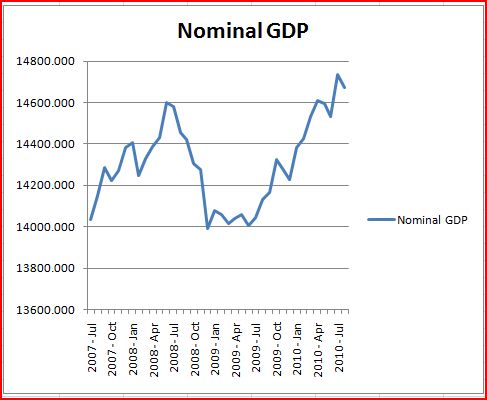

Matt also mentioned commercial real estate in the US, but I don’t think that proves what he wants it to prove. As you know, the profession has not accepted my argument that lack of AD, not the banking crisis is responsible for our macroeconomic problems. But the one weakness in my argument is that the subprime bubble blew up well before the recession. This leads Matt to draw a connection between the financial crisis and the recession.

Banking activities need to be regulated or else asset price fluctuations will lead to macroeconomic instability.

That’s why the stakes in this debate between progressives and libertarians are seen as being so high. If it was just the TARP bailout, I’m not sure people would care that much. The big banks are repaying the loans. Indeed I’ve seem progressives praise the auto bailout, even though GM may never pay back all the money. No, the reason this is so important is that it’s seen as a crisis that led to 9.2% unemployment three years later. Fair enough.

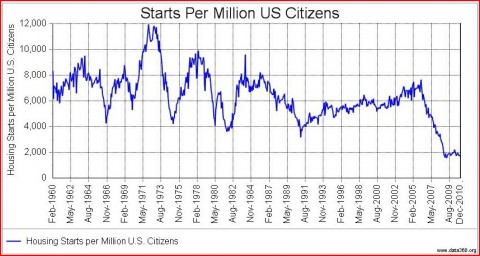

But in that case Matt can’t use commercial real estate, as that was clearly a symptom of the recession. Indeed commercial RE was still booming in mid-2008, and only turned south toward the end of the year. Now in fairness to Yglesias, the fall in commercial RE did bring down lots of smaller regional banks, and this resulted in costly FDIC bailouts of depositors. If we insist on having FDIC (a big mistake in my mind), and insist on not reforming it by placing $25,000 caps on insured deposits (and even bigger mistake), then yes, we need to regulate banking. We tried to re-regulate after the 1990 S&L debacle, and it didn’t work. We tried again with Dodd-Frank, and again failed to deliver an effective set of regulations (like, umm, banning subprime loans, for instance.) But I would agree that in the presence of FDIC, a completely unregulated banking system will take far too many risks. I don’t consider that the failure of “laissez-faire”, I view it as the failure of a banking system where much of the liabilities are essentially nationalized.

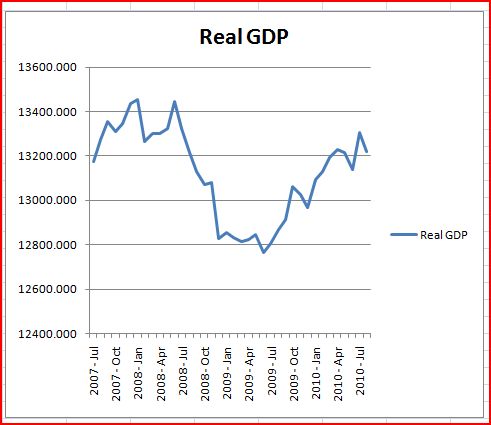

PS. Interested readers may want to play around with the Economist’s interactive graph at this link:

It’s a bit hard to read the graph below, so a few comments. The steady drop (orange line) is Japan. The only other two countries down in real terms from 2001 are the US (grey) and Ireland (green, of course.) Spain is a rather dark line that rises steadily to almost 180, then slips back to 140. As I see the graph, most other countries had substantial real price run-ups, like the US, but then real prices trended sideways. This shows that not everything that goes up must come down. I see lots of commenters patting themselves on the back about how they predicted the bubble would burst. Count yourself lucky that you live in America; otherwise you probably would have been wrong. Germany is not listed because of incomplete data, but it had no bubble in the first place.

Also note that the default option is nominal prices, which is actually more supportive of my “very few bubbles” claim. I converted to real for the graph below, which puts more of a downward bias on prices after 2007.