Is Fannie&Freddie spelled ‘Caja’ in Spanish?

Matt Yglesias recently made this remark in a post criticizing Tyler Cowen’s assertion that the GSEs significantly worsened the US housing/banking crisis:

The part where unwise public policies to subsidize homeownership would seem to come into this is step (1), but we in fact see this happening in many markets (Spain, commercial real estate) where Fannie and Freddie weren’t players.

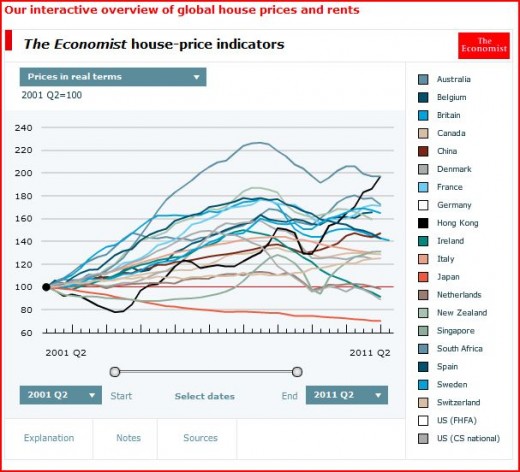

I’m not sure what Matt means by “many markets.” According to the interactive housing price graph constructed by The Economist, only the US and Ireland experienced major housing bubbles. Spain had a smaller one (although I suspect more accurate figures would show a more serious price decline in Spain.) Japan and German also saw price declines after 2006, but they had had zero price run-up before 2006–so no bubbles there. The vast majority of industrial countries saw big increases in real housing prices between 2001 and 2006, just like the US. But unlike the US, prices tended to move sideways after 2006, even in real terms. (Of course you can find some brief price dips in the severe 2008 recession, but nothing like the long collapse in the US, which pre-dated the recession.)

But let’s take a look at Spain. It’s true that Spain does not have a single institution called “Fannie Mae.” But do they have a similar problem of governments deeply involved in promoting real estate lending? I’m no expert (and I welcome critiques) but my initial impression is that the answer is yes. Here’s The Economist:

Another duality lies in the banking system. Observers fret that the Spanish state may have to pump a lot more money into the banks than the roughly €25 billion ($36 billion), or 2.5% of GDP, it currently reckons will be the total bill from Spain’s epic housing boom and bust (Ireland’s bank bail-out bill is over 40% of GDP).

The problem is concentrated in the cajas, local savings banks that make up around half the domestic banking system, rather than big Spanish banks like BBVA and Santander, which are protected by big international businesses. Not before time the government is overhauling the cajas. Their ranks are being slimmed””the number has fallen from 45 to 18″”and they are being reorganised as joint-stock companies that can raise equity capital. José Maria Roldan, director-general of banking regulation at the Bank of Spain, says that the reform is “a huge step forward, replacing the caja model with a standard banking template that is more secure and comprehensible to international investors.”

So I decided to further investigate the cajas, and this is what I found (also from The Economist):

IN THE end CajaSur trusted in God. On May 22nd the small savings bank (or caja), which is controlled by the Roman Catholic church in Córdoba, was seized by the Bank of Spain after failing to agree on a merger with Unicaja, a larger Andalusian rival. The move shocked investors and prompted other savings banks to hasten consolidation. But mergers between wobblier cajas, which are unlisted and make up close to half of Spain’s financial system by assets, are merely a first step in a longer process.

CajaSur is tiny, holding just 0.6% of Spain’s financial assets. Yet its seizure unsettled investors for two reasons. First, it was a reminder that politics often trumps rationality.

. . .

The politicians who control the cajas like this virtual structure because it allows the banks to keep their own brands, governing bodies and local retail operations while combining treasury and risk-management functions.

. . .

Encouragingly, both the government and the opposition have agreed to reform the law governing savings banks.Attracting private capital requires other changes, too, such as a reduction in the influence of politicians, something caja managers would relish. Greater openness about banks’ balance-sheets would also help: on May 26th the Bank of Spain moved in this direction by announcing plans for tougher provisioning rules.

“The politicians who control the cajas”? I thought banks were supposed to be controlled by businessmen, not politicians. I’m still no expert on Spanish banking. But I’d wager that further investigation would turn up the same incestuous relationship between politicians and the cajas that we saw between politicians and the GSEs.

So we observed clear-cut housing bubbles and busts in just two countries with more than 5 million people; the US and Spain. And both suffered from the same problem—politicized institutions that will require massive transfers from the public. Both also had large private banks that made mistakes, but at least they didn’t impose huge burdens on the taxpayers.

Matt also mentioned commercial real estate in the US, but I don’t think that proves what he wants it to prove. As you know, the profession has not accepted my argument that lack of AD, not the banking crisis is responsible for our macroeconomic problems. But the one weakness in my argument is that the subprime bubble blew up well before the recession. This leads Matt to draw a connection between the financial crisis and the recession.

Banking activities need to be regulated or else asset price fluctuations will lead to macroeconomic instability.

That’s why the stakes in this debate between progressives and libertarians are seen as being so high. If it was just the TARP bailout, I’m not sure people would care that much. The big banks are repaying the loans. Indeed I’ve seem progressives praise the auto bailout, even though GM may never pay back all the money. No, the reason this is so important is that it’s seen as a crisis that led to 9.2% unemployment three years later. Fair enough.

But in that case Matt can’t use commercial real estate, as that was clearly a symptom of the recession. Indeed commercial RE was still booming in mid-2008, and only turned south toward the end of the year. Now in fairness to Yglesias, the fall in commercial RE did bring down lots of smaller regional banks, and this resulted in costly FDIC bailouts of depositors. If we insist on having FDIC (a big mistake in my mind), and insist on not reforming it by placing $25,000 caps on insured deposits (and even bigger mistake), then yes, we need to regulate banking. We tried to re-regulate after the 1990 S&L debacle, and it didn’t work. We tried again with Dodd-Frank, and again failed to deliver an effective set of regulations (like, umm, banning subprime loans, for instance.) But I would agree that in the presence of FDIC, a completely unregulated banking system will take far too many risks. I don’t consider that the failure of “laissez-faire”, I view it as the failure of a banking system where much of the liabilities are essentially nationalized.

PS. Interested readers may want to play around with the Economist’s interactive graph at this link:

It’s a bit hard to read the graph below, so a few comments. The steady drop (orange line) is Japan. The only other two countries down in real terms from 2001 are the US (grey) and Ireland (green, of course.) Spain is a rather dark line that rises steadily to almost 180, then slips back to 140. As I see the graph, most other countries had substantial real price run-ups, like the US, but then real prices trended sideways. This shows that not everything that goes up must come down. I see lots of commenters patting themselves on the back about how they predicted the bubble would burst. Count yourself lucky that you live in America; otherwise you probably would have been wrong. Germany is not listed because of incomplete data, but it had no bubble in the first place.

Also note that the default option is nominal prices, which is actually more supportive of my “very few bubbles” claim. I converted to real for the graph below, which puts more of a downward bias on prices after 2007.

Tags: housing bubble

18. July 2011 at 14:24

Some notes I got from a buddy in space:

84M homes in US

56M are mortgaged – 68%

5M on the market

11M more currently underwater

7.4M of the 11M will be liquidated

——-

Scott, TARP sucked giant donkey balls.

Whether it was paid back mean NADA, what sucks is that all those houses did not get sold in $1 auctions within months of the crisis.

Scott, please stop moving your pile of aggregates around on the table and FOCUS on the real explanation being given for CURRENT CRISIS.

The bankers were SUPPOSED TO LOSE..

But smart SMB / Tea Party style guys with $$ they took out of the market early, were supposed to get to buy up 12M cheap houses for pennies and the dollar..

They were supposed to drop rents like crazy…

And people were supposed to NOT MOVE IN WITH THEIR COUSIN/PARENTS/ROOMATES etc.

That is the problem today. I repeat THAT IS THE PROBLEM.

——

Look, if you aren’t going to admit that THE PROBLEM is that banks got saved, then you have a really hard time saying we shouldn’t have minimum wage.

If the banks don’t get saved, housing prices / rents fall, and that makes cutting minimum wage easier. Everything lines up.

Imagine the 20M people who are currently living with someone else, stop pretending they are ALL unemployed.

Focus your policy suggestions NOT on them getting paid in inflated dollars, focus on deflating their rents – until they move out.

18. July 2011 at 14:42

There is every reason to believe that a price distortion caused malinvestment bubble will have goegraphica distributional characteristics — as it had in the U.S.* — which are obscured by national aggregation.

*CA, AZ, MI, FL, NV etc.

18. July 2011 at 15:05

The systematic price distortions behind malinvestment bubbles comes from multiple causes working in same direction: Fed policy, China money, Fannie Mae, regs allowing massive Wall Street leverage, lack of transparerancy, CRA pressure degredation of lending standards, mindless quant thinking on Wall Street, the Greenspan put — all pushing to systematically distort vast array of relative prices across time in same direction.

18. July 2011 at 15:08

Note well: systematic relative price distortions also created a massive bubble and bust in shadow money, as Sweezey & Lantz of Credit Suisse explain. Ovepriced houses became cash piggy bank for consumers, became a phantom liquid asset security in mortgages back securities and credit default swaps, etc.

When shadow money ex

18. July 2011 at 15:09

I infer from the above and past posts that you believe capital markets are efficient but housing markets are not. Am I reading you right? Because if housing market is efficient then that rules out bubbles, unless all we mean by bubbles is a big run up and a big run down.

There is certainly more reason to believe that housing markets are not efficient (transaction costs, thin markets, information costs, inability to short, lack of diversification), but the degree of inefficiency seems both important and not actually a well measured quality. To attribute the run-up and run-down to an asset market bubble ignores 1) The immigration crackdown you are often mentioning, 2) That between productivity growth and unemployment, that we aren’t as rich as we once were, both lowering demand for housing and land.

There is plenty of real economic cause on the demand side that I’m not sure we need a bubble-driven explanation.

18. July 2011 at 15:10

Note well: systematic relative price distortions also created a massive bubble and bust in shadow money, as Sweezey & Lantz of Credit Suisse explain. Ovepriced houses became cash piggy bank for consumers, became a phantom liquid asset security in mortgages back securities and credit default swaps, etc.

When shadow money expanded, demand for money dropped, when shadow money collapsed, demand for cash balances expanded.

Ideas straight out of Hayek, as Sweezey & Lantz point out.

18. July 2011 at 15:20

With respect to F&F:

As of 2009 Q1 the entire federal government (including Fannie and Freddie) owned or guaranteed only 32 percent of seriously delinquent loans despite holding 67 percent of all mortgages. In contrast the private mortgage financing channel, which did not involve the federal government at all and was policed only minimally, generated only 13 percent of outstanding loans but was responsible for 42 percent of serious delinquencies. (Slide 13):

http://www.fhfa.gov/webfiles/2919/Lockhart_Speech_to_National_Association_of_Real_Estate_Editors-06-18-09.pdf

The UK, Iceland, Ireland, Spain, and Denmark all suffered from contemporaneous credit crises and have no government institutions that are really analogous to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or Ginnie Mae.

On the other hand Canada does have an institution very similar to Fannie/Freddie/Ginnie (the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation). And yet Canada, unlike the United States and many other countries that experienced a recent housing bubble, did not have a major surge in unregulated lending and new product types, as private-label securitization remained negligible:

http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2010/08/pdf/canadian_banking.pdf

That’s not to say government policies didn’t help promote the housing bubble. But the claim that it was F&F is a zombie lie.

18. July 2011 at 15:53

More on shadow money from James Sweeney & Carl Lantz of Credit Suisse here:

http://hayekcenter.org/?p=2954

18. July 2011 at 15:59

Mark A. Sadowski, the biggest fraud in the boom-bust spin book is to ascribe a mono-cause view to anyone ….

18. July 2011 at 16:05

Note how Japan neatly avoided the housing “bubble”: Their prices were going down, and kept going down, for the entire decade.

18. July 2011 at 16:45

Morgan, OK, we shouldn’t bail out banks.

Greg, Yes, regional conditions vary greatly. But even relatively well off states like Massachusetts are in deep recessions.

OneEyedMan, I think housing markets are efficient, and I define ‘bubble’ as a big run up and run down (in this post.) If you define bubbles as prices that are obviously too high, then I don’t believe in bubbles. I may have used that alternative definition in other posts.

Mark, You said;

“With respect to F&F:

As of 2009 Q1 the entire federal government (including Fannie and Freddie) owned or guaranteed only 32 percent of seriously delinquent loans despite holding 67 percent of all mortgages. In contrast the private mortgage financing channel, which did not involve the federal government at all and was policed only minimally, generated only 13 percent of outstanding loans but was responsible for 42 percent of serious delinquencies. (Slide 13):”

I have trouble seeing how that’s relevant. We are spending hundreds of billions bailing out F&F, while the big banks paid back their TARP loans. Can someone tell me why I should care about anything else at all?

I’m not defending the big banks, they behaved irresponsibly, but F&F did far more damage.

You said;

“The UK, Iceland, Ireland, Spain, and Denmark all suffered from contemporaneous credit crises and have no government institutions that are really analogous to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or Ginnie Mae.”

I recall reading that Denmark’s banks came through the crisis much better than ours, indeed Joe Stiglitz was touting their banking model. Have the progressives moved away from Denmark? I hadn’t heard that. Ireland’s banking system was very politicized and corrupt, from what I read. Iceland basically looted Britain and Holland to engage in a giant real estate speculation. I’ve just talked about Spain. It seems to me that bad government policies are deeply embedded in all these cases. I’m not saying they are all exactly like the US, but it’s always the same sort of problem–governments hellbent on encouraging real estate development. I’ve advocated the Canadian system in the past, which does not encourage home ownership to anywhere near the extent we do.

Obviously the Canadian GSE is nothing like ours as they didn’t require a $200 billion bailout. Or any bailout.

You said;

“That’s not to say government policies didn’t help promote the housing bubble. But the claim that it was F&F is a zombie lie.”

You don’t have a shred of evidence to back that up. They were heavily involved in encouraging subprime mortgages, THAT’S WHY THEY’VE LOST $100S OF BILLIONS OF DOLLARS. Once again, a housing bubble isn’t a problem, a multi-hundred billion dollar taxpayer funded bailout is a huge public policy problem. The defenders of F&F are talking about the wrong issues. It boggles my mind that an institution can lose hundreds of billions, probably more than any other institution in the history of the planet, and people can say they didn’t encourage risky loans. Why did they lose money then?

Benjamin, Finally a voice of reason.

18. July 2011 at 16:53

Scott,

So then you agree with my point, the CAUSE of this recession, is that we bailout banks.

And ever since then, Fed actions including QE have been kicking the can, rather than fixing the economy by forcing the banks into submission.

The question is what policies can you come up with that will force the banks into insolvency?

1. end IOR

2. bring back mark to market (which I remember you being against – am I correct?)

what else you got, what screws the bankers and makes the guys with ready cash jump for joy?

18. July 2011 at 17:12

As any economists should understand, relative prices are an interconnected network. And like a physical net, when systematic distortions pull at the net in systematic ways, the whole network of relations is distorted — systematically.

According to the Hayekian causal mechanism, systematic stretching distortions & contractions play out across time, and goes through various nodes across time, and also involves systematic distortions touching all nodes (some more, some less) through the expansion and contraction of shadow money do differing degrees, in differing hands.

So this does not count against the causal mechanism at all, which is a multi-causal model taking time to work its way throughout the net. I.e. the collapse of shadow money due to the collapse of housing prices (etc.) can have significant consequences down the road for parts of the economy without large housing price swings.

Scott writes,

“Greg, Yes, regional conditions vary greatly. But even relatively well off states like Massachusetts are in deep recessions.”

18. July 2011 at 17:28

Here is a graph of unemployment rates by state charted against the rate of construction growth / decline, 2005-2010:

http://calculatedriskimages.blogspot.com/2011/06/unemployment-rate-and-residential.html

The graph is from this Calculated Risk blog post, which also contains links to some published work on the topic:

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2011/06/unemployment-rate-and-residential.html

Here’s a data point from where I live, the home of the sub-prime mortgage origination industry & very likely the biggest housing boom – bust region in the country in terms of total dollar value:

The Orange County, CA overall unemployment rate last month was under 10%, the unemployment rate in construction industry last month was just a hair under 40%.

18. July 2011 at 17:44

I absolutely agree with Morgan again. Bank bailouts are the worst mistake a country can make. Japan, Ireland, and the US of A are gonna continue to pay heavily for the decision while Iceland, who made every mistake in the book except bailing out the banks, will probably recover.

18. July 2011 at 18:07

Scott, the numbers I read are that 1 of every 4 jobs lost in the recession has been a construction job.

The ratio is significantly higher in some areas, such as Orange County, CA.

There is also significant job loss in all sorts of housing & construction related industries, including but not limited to real estate, finance, home furnishing, forestry & lumber, home furnishing, etc.

Also noteworthy, there was a 30% decline in auto-plant jobs — another time sensitive, credit sensitive, capital intensive industry / long period production good.

18. July 2011 at 18:14

Just a bit on the Canadian morgage and housing corporation(CMHC). I would like to point out that the CAP is surprisingly uninformative and partisan for a report on a Canadian institution

😉

The CMHC is totally different in structure from fannie and freddie. the first thing to point out is that CMHC is explicitly a body of the Canada government and whose profits are subsequently returned to the treasury(their salaries also track very closely the civil service pay-scale). the second thing to point out is that CMHC assumes only default risk on the mortgages that it insures. interest rate and liquidity risk is entirely held with the mortgage issuer/lender. there is no trading or interaction with the servicing of the mortgage beyond the premium that it overlays on Canadian mortgages that have less than a 20% down payment. moreover, this premium is built on top of the premium by the mortgage issuer/holder entailing that CMHC only needs to price the relative risk of the mortgage. this is much more in a manner to a traditional insurance company than the hedgefundesque fannie and freddie.

18. July 2011 at 18:27

Greg,

A lot of people have pointed to decline in construction and manufacturing jobs as an example that unemployment is structural. However, those industries also happen to be the most cyclical. The unemployed do not buy new homes or cars, which is why unemployment generally increases most in these industries even in purely cyclical recessions.

18. July 2011 at 18:34

Morgan,

“So then you agree with my point, the CAUSE of this recession, is that we bailout banks.”

We had a rather deep recession 1929-33 even though there was zero bank bailouts, not even the FDIC.

The issue with bank bailouts, at least without appropriate regulation like we had 1933-1980 or so, is that banks have an incentive to misallocate capital. Eventually taxes will have to be increased to bail out the banks. That transfer means a deadweight loss, a reduction in our standard of living and a surplus to banks lucky to be Too Big to Fail.

That does NOT explain 9.2% unemployment, though. Unemployment happens solely due to some sort of market failure in the labor market. When AD declines precipitously, sticky wages act as a minimum wage for nearly the entire workforce. That’s why we had massive increases in unemployment 1929-33 and 2008-09. Wages simply do not adjust to their clearing levels.

So, having either better regulation or no bank bailouts is a worthy cause for our future standard of living. But if you want to decrease unemployment, you need to fight declining AD.

18. July 2011 at 18:51

Sorry for all the posts, but if you look at price-to-rent ratios, it looks like Britain, France and Spain had worse bubbles and Denmark had a similar magnitude bubble as the US.

Price-to-rent ratios are affected by many things, but fundamentally they represent the premium on owning your house rather than renting. People should pay a premium for having the stability and power of home ownership. However, if that premium increases because people think house prices could never go down and therefore they’re a great investment, that premium is not sustainable. In the long run, the premium will decline to reflect the value of owning rather than renting.

Australia and Canada price-to-rent ratios are interesting though. Either case could fundamentally be changing consumer tastes for ownership, increasing the premium of owning vs. renting. But I’m not sold that an Australian bubble doesn’t exist just because the market hasn’t declined. I’m not sure a bubble DOES exist, but I won’t say it doesn’t exist either. Bubbles can go on for years. Greenspan’s famous “irrational exuberance” speech, for example, was given four years before the stock market bubble eventually peaked.

18. July 2011 at 19:07

From Ryan Avent:

…The government’s ability to affect real growth is constrained, but real growth is highly correlated with nominal growth, and the government’s ability to influence nominal growth is absolute. The Federal Reserve could commit to faster nominal GDP growth and begin using the tools available to get there. Some portion of the growth in nominal GDP (and I’m willing to bet the lion’s share) would represent a real increase in output. The outlook for investment would look better, employment conditions””and expected incomes””would improve, asset values would rise, and deleveraging would quickly (almost as if by magic) seem like less of a problem. Or maybe the Fed’s efforts would translate into little new growth and lots of new inflation. That’s hardly the worst outcome; a few years of above-target inflation would go a long way toward easing debt burdens.

So yes, it’s true that growth is slow and that deleveraging is a factor influencing the trajectory of the recovery. But you have to put household debt in the appropriate context. Mr Leonhardt’s argument comes too close to absolving the government of the responsibility to make policy appropriate to the state of the economy.

http://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2011/07/americas-jobless-recovery-0

18. July 2011 at 21:11

nunes, you avent and scott ALL refuse to really count the kick-ass economic growth that comes from 12M homes being liquidated in $1 auctions.

It’s the V baby! get down and wallow around in it!

Imagine the backbone of this country, the Tea Party rich – the big fish in small ponds all over America:

1) smugly smiling as they but up the REO homes all over their town for pennies on the dollar.

2) imagine them paying non-union construction workers to FINALLY fix up the fallow housing, they NOW OWN.

3) imagine them generously handing the poor bastards living in their cousins/parents homes super cheap rents that still return 10% YOY.

4. imagine the fallow housing stock SOLD, and demand suddenly being REAL.

—–

could you all please stop pretending this is an intellectual exercise and ADMIT YOU HATE the idea of country club Republicans all over America suddenly getting to buy up 1/8 of the housing stock, killing stock prices on wall street, and PUSHING themselves into even greater economic and political control against the mean.

you people are not honest. that’s the problem.

18. July 2011 at 21:13

Sort of related, but how do housing markets work in other countries? I’ve never really looked into it, but I have European friends from the Netherlands and Denmark who managed to buy condos when they were in grad school (!) so I imagine there’s subsidies involved. Anyone have any good resource for someone curious?

18. July 2011 at 21:19

Matt, declining “AD”is a joke.

The entire future economy is based on:

1) network effects.

2) things becoming free. meaning the more people who get it the cheaper is gets. Think of it as nearly freezing profit and spreading it out over more customers, and therefore conventional growth freezes on any invention.

3) what matters is “how long” it takes the average lower class worker to be able to toast his bread, buy his 100Mbps broadband, get fake tits for his girlfriend – FREEZE any one of those things, and as the relative price of it comes comes down – THAT is economic growth. The fact that you guys aren’t set up to measure it properly just means your are worthless, nothing else.

18. July 2011 at 21:22

Matt, the causal ordering of actual events does NOT fit your “cycle” story. The drop off in houses and cars came before the full onset of unemployment.

The “cyclical industries” hand waving remains non-explanatory. Descriptions are not causal processes.

18. July 2011 at 21:45

Matt, you don’t seem to understand that there is a category of unemployment outside of your classification scheme.

When their is systematic distortions across all price relations, across time, and across all production processes & consumption plans, there can be discoordination unemployment causaed by artificial boom labor misallocation and inevitable bust labor crashes, which will partially recover once supplies and demand grope closer to sustainable equilibrium paths.

This fits neither the “cyclical industries” deficient agg demand / downward spiral story, nor the permanent job loss “structural” unemployment story.

Minds cast in the cement of the framwork beat into them as math students have a hard time allowing themselves to be flexible enough to think new thought and conceive of new categories and new ways of perceiving processes in the world.

18. July 2011 at 22:17

Morgan,

Clearly you will believe what you will believe and nothing will sway you. But the “future economy” you describe is a tiny portion of the economy. “Network effects” have no bearing on things like health care, education, manufacturing, construction, 99% of retail, tourism and even most IT and media.

I’m not sure what your definition of “economy” is. Maybe there is a more expansionary definition to include non-economic activities. For example, I’m “producing” a blog comment right now but I am currently adding zero to the US GDP. But I think when people talk about the economy, they are talking about unemployment, inflation, the flows of money, living standards, etc. Blog comments can only do so much for living standards and unemployment.

To fix unemployment, companies need to see demand for their products, i.e. Aggregate Demand, or AD. In a perfect world, if declining AD pushes wage equilibrium went down 10%, all wages across the board would go down 10%. In the real world, though, that doesn’t happen. Across-the-board wage cuts are a last ditch option for companies near bankruptcy. Instead they reduce head count or, if they don’t reduce head count, they reduce hours. That’s where you get your unemployment, and certainly not “network effects” or bandwidth.

Greg,

It seems that you are describing structural unemployment. If construction employment unnaturally increased due to government intervention in the housing market, then we would build more than we need and soon those construction workers would be unemployed. That is structural unemployment, i.e. skill mismatch. Those construction workers can’t become software engineers overnight.

However, that is only part of the story. As Scott shows, real household formation has plummeted to one of the lowest levels in history the past few years. I am not talking about new housing construction, but new physical families moving into physical homes. The decline in new household construction has unduly hurt housing construction. I do not expect Orange County home construction to recover, but I do expect a healthy amount of construction in places like Dallas or Houston. That isn’t happening though.

And why has new physical household formation declined so much? Because demand for new home construction is more cyclical than demand for, say, health care or education. Unemployed people, or people worried about their jobs, do not go out to buy new homes or cars. Why are they worried about jobs? Because unemployment is high. Why is unemployment high? Because people are worried about their jobs or out of a job. And so on. To get around the cycle, you have to increase AD.

18. July 2011 at 22:20

Er, “The decline in new housing construction” above should be “The decline in new household formation.”

18. July 2011 at 22:35

I have only a peripheral observation that there seems to be selective use of data in this article, in order to validate a premise. Ireland is excluded so as to use one phrase from the Econoomist to cast total blame for the RE bubble back onto the GSEs. Ireland is excluded as not being among the two countries having more than 5 million people that experienced housing bubbles. This exclusion left only Spain and the USA, and we’re offered the thesis that the Cajas in Spain, like the GSEs in America, were politically controlled, ergo such institutions were the root cause. Aside from the other logical fallacies, let me point out that in 2008, Ireland had a population of over 6 million, and that has fallen to under 5 million only since their housing bubble collapsed, due to rapid outmigration of workers who had been attracted to the “Celtic Tiger.” So perhaps the author should have drawn the line at “under 7 million” population. But best yet, why not drop all artifice and try for a theory that embraces Ireland? Perhaps because such a comprehensive theory would not suit the GSE blame conjecture.

In passing, I will observe that the Spanish real estate boom was widely known to be feeding escalating demand from buyers in countries to the North, hungering for reliable sunshine. It is unlikely that the political control of the small cajas (asserted by the Economist) had any role in boosting the demand flowing from the UK, Russia and Germany. I really cannot find any corroboration of the political influence alleged in Spanish banking or, more important, any analysis of the objectives and techniques of that influence. Spanish housing was overbuilt to an extent probably exceeding any other country on earth, hence the collapse. Australia has perhaps the most unaffordable housing in the world, so it is certainly in a bubble, but the bubble does not pop because land development and house construction is tightly controlled, leading to huge scarcity. Many immigrants have corporate backing to buy houses

18. July 2011 at 22:52

Canada also (generally) does does not ration land use to anywhere near to the same extent that the various bubble localities did. Means a lot less for expectations of capital gains to work on.

On bubbles, it is hard to keep one’s language straight. I have probably said “overvalued” somewhere where I meant “based on expectations of capital gain in excess of income value”, but “premium for ownership” is pithier.

Greg: as I have noted before, don’t believe the term ‘malinvestment’ is useful, since whether something is a good investment or not is contingent on conditions. The notion of ‘malinvestment’ smuggles in some notion of “intrinsic value” that Austrians, of all people, should stay away from.

19. July 2011 at 01:13

Bologna. It doesn’t do this at all. Some conditions are systematically interconnected over time. It doesn’t have anything to do with ‘intrinsic value’. You are simply making cognitive errors here.

“Greg: as I have noted before, don’t believe the term ‘malinvestment’ is useful, since whether something is a good investment or not is contingent on conditions. The notion of ‘malinvestment’ smuggles in some notion of “intrinsic value” that Austrians, of all people, should stay away from.”

19. July 2011 at 01:15

Matt, you are NOT comprehending the Hayek causal mechanism, you are retranslating all the terms back into the old cement blocks you learned as a math student.

Turing Test FAIL.

19. July 2011 at 04:07

Scott,

NPR’s Planey Money tells a fascinating and similar story about the politicization and cronyism pervading Spain’s caja system:

http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2011/01/04/132658358/the-tuesday-podcast-marrying-off-spains-troubled-banks

I think it’s a must-listen.

Tony

19. July 2011 at 04:11

the GSEs will also pay back all or most of what they borrowed, unless we have a severe double-dip. so by your logic they aren’t a problem. why do you focus on them?

19. July 2011 at 06:08

Matt, you are naive.

“Network effects” have no bearing on things like health care, education, manufacturing, construction, 99% of retail, tourism and even most IT and media.

Uhm…

1. A college education will come free when you buy a 120” LED TV.

2. The time window on patented drugs is remarkably short. In just 10+ years Viagra can cost 10 cents a pill. And IT GETS FAR CHEAPER when suddenly everyone has to pay cash for their generic drugs.

3. BIOTRACKING is just beginning. Altho, this is an interesting note, HEALTH should continue to capture a larger part of GDP, because rich people with money HAVE TO SPEND it somewhere – staying alive is #1 concern.

4. You should study up on 3D printing.

5. You should play with spotify, rdio, and pirate bay – and then check TICKET PRICES since 1998. As music became free, the cost of becoming a fan any given band approached zero… which increased demand for tickets.

“of course I want to go see X, I have ALL her albums!”

—–

Overall though, please realize I have already 100% solved for Unemployment with my Guaranteed Income plan:

http://biggovernment.com/mwarstler/2011/01/04/guaranteed-income-the-christian-solution-to-our-economy/

Which Scott and I’d say even most realistic Austrians support.

19. July 2011 at 06:46

@Warstler: “Overall though, please realize I have already 100% solved for Unemployment with my Guaranteed Income plan”

And just like that he became a Post Keynesian:

http://moslereconomics.com/mandatory-readings/full-employment-and-price-stability/

19. July 2011 at 07:33

Morgan, No, I don’t agree.

Greg, It’s no surprise that state that experienced a big housing slump have higher unemployment. That would be true if the US had not experienced a recession at all.

And as I said many times, the fraction of lost jobs that are in construction has no bearing at all on the whether the housing bubble triggered the recession. You’d want residential construction jobs lost, which is a far lower number than total construction jobs lost. How can you come up with sensible theories I you don’t even know the data that fits your theory?

Now I expect you to tell me that the Austrians don’t believe housing is the issue.

You do understand that every single business cycle model predicts capital goods output will fall more sharply than consumer goods output–don’t you? So why even discuss the issue?

John. I agree about bank bailouts.

honeyoak, Thanks for clearing that up–I suspected it was nothing like our GSEs.

Matt, I agree with your first few posts, but not this:

“Australia and Canada price-to-rent ratios are interesting though. Either case could fundamentally be changing consumer tastes for ownership, increasing the premium of owning vs. renting. But I’m not sold that an Australian bubble doesn’t exist just because the market hasn’t declined. I’m not sure a bubble DOES exist, but I won’t say it doesn’t exist either. Bubbles can go on for years. Greenspan’s famous “irrational exuberance” speech, for example, was given four years before the stock market bubble eventually peaked.”

This is flat out wrong. All markets go up and down, even markets with no bubbles. Some day Australian housing prices will decline, but even then the Australian bubble predictors of 2005 will have been 100% wrong. Just as Greenspan was wrong in calling a stock bubble when the DJIA was 6400. No, that wasn’t a unwarranted level for the DJIA in 1996. I find it frustrating that any time a market falls the bubble predictors say they were right. Don’t people know that ALL VOLATILE MARKETS FALL ON OCCASION? It certainly doesn’t mean the market was a bubble before the fall. (Here I’m assuming bubble means EMH doesn’t hold.)

marcus, Thanks, another good Avent post.

Aaron, I don’t know much about those markets.

Greg, You said;

“The “cyclical industries” hand waving remains non-explanatory. Descriptions are not causal processes.”

It truly frightens me that you don’t realize that all other macro theories also have causal explanations. I just gave you an example the other day.

Critz, You argued:

“It is unlikely that the political control of the small cajas (asserted by the Economist) had any role in boosting the demand flowing from the UK, Russia and Germany.”

These arguments always make me scratch my head. Spain had a big real estate bubble that popped. Most of the losses were incurred by cajas. Yet they played no role in boosting the bubble? Did someone put a gun to their heads, forcing them to make loans to rich German retirees? No one would be complaining about the bubble if the banks hadn’t failed. That’s why it’s a big issue. So why shouldn’t we focus on the banks that, you know, actually failed?

And I have no problem including Ireland, which also had a corrupt and highly politicized banking system.

Lorenzo, That’s a good point about Canada.

Greg, You said:

“Matt, you are NOT comprehending the Hayek causal mechanism, you are retranslating all the terms back into the old cement blocks you learned as a math student.

Turing Test FAIL”

You fail to explain your points in a fashion that any of us can understand. Communication test FAIL.

Once again, all macro theories have causal mechanisms for why capital goods are more cyclical. That’s something you need to know, if you plan on going around saying only the Austrian theory has that sort of causal explanation.

Thanks Tony.

q, Based on what I’ve read they aren’t expected to.

19. July 2011 at 07:40

Scott, as an investor I am familiar with the cajas. They are run much more overtly as political vehicles than the GSEs. Individual cajas are often identifiable with one of the two ruling parties. It is analogous to the Texas Republican Party being able to install a board of directors (including CEO) at a mid-sized bank operating mostly in Texas. The boards are usually packed with ex-politicians looking for sinecures as well as lawyers and businessmen linked with the controlling political party, either PSOE or PP. (Yes, there are some legitimate businessmen as well; they are often a minority though.) In turn many – I say many not “all” as some have been extremely responsible and conservative – cajas loaned money to politically-connected developers to buy huge land banks. Excess profits (beyond those used to grow the caja) went to charities that enhanced the political party’s regional reputation.

At least the GSEs have “hard” collateral to fall back on, in the form of buildings (which may or may not have their copper wiring left, though). Many cajas are left with only land (down 90% in Spain’s exurbs since the peak) or the developer’s “personal guarantee” which amounts to very little.

As far as the scale of the problem, see the Q1 bulletin from the Bank of Spain:

http://www.bde.es/webbde/es/estadis/infoest/a0413e.pdf

http://www.bde.es/webbde/es/estadis/infoest/a0418e.pdf

From the 2nd PDF: Real estate activities (basically developers with land banks or finished/unfinished homes) makes up 312b EUR of Spanish banking assets. Another 110b EUR of construction loans, some of which are residential with little end-demand for the houses/apartments. From the 1st PDF: Retail loans for home purchases (mostly mortgages) are 628b EUR. A big difference between the U.S. and Spain: due to strict personal recourse laws, Spanish are essentially “stuck” in underwater-equity homes (would be interesting to debate recourse on the blog!). So the NPL ratio here is only 2.5%. On the other hand, the NPL ratio for developers is 15% and the ratio for construction loans is 13%. (I also have good reason to believe the NPL figures for developers and construction loans, as well as possibly retail mortgages, are dramatically understated.)

Note these figures are systemic and include both banks and cajas (many banks have been poor stewards of capital as well, though not as bad as the worst cajas like Cajasur, CAM, etc. Overall the asset breakdown between cajas and banks is 50/50 (out of 2.8b EUR total financial assets); not sure about the real-estate asset breakdown between cajas and banks though.

19. July 2011 at 08:00

Tony, That podcast was quite interesting, I was surprised to learn these were not-for profits. So the epicenter of the failure of capitalism in this crisis is a non-capitalist sector of the Spanish economy.

Sean Thanks for all the info, it sounds like you know a lot about these issues. Those observations all strike me as being very plausible.

19. July 2011 at 09:00

Matt’s “cyclical” story was a causal faill.

I understand there causal stories like Matt’s.

But your description Scott did not offer one.

Sometime you will have to explain what just part of Hayek’s causal mechanism you don’t understand.

I’ll list the for you and they you tell us all just what you don’t comprehend.

19. July 2011 at 09:36

Let’s be clear, I pointed out a fact. Hayek’s causal mechansim invokes the misdirection of labor and capita due to the lengthening and shortening of the capital, invoking the fact that people will not lengthen a production process unless that process promises greater output, and esplaining how systematic price distortions across all prices and across time can produce this lenthening and shortiening.

If other work in macro invokes the same causal mechanism, show it to me, Scott.

I did NOT say that the other macro constructs failed to attempt to come up with causal mechanism for cycles in capital goods. Once again, you ascribe views to me that I did not say and did not even hint — for whatever purpose you repeatedly do this kind of thing I can’t imagine.

“Once again, all macro theories have causal mechanisms for why capital goods are more cyclical. That’s something you need to know, if you plan on going around saying only the Austrian theory has that sort of causal explanation.”

19. July 2011 at 10:49

thruth,

read up on my articles, I hack MMT using the least amount of government $$$ (MUCH smaller than today), and by putting workers into a jobs where profit is taken from their labor by private interests.

Solving for unemployment is super easy with the Internet – we need use nothing more than copies of the EBay and Paypal code base.

If Uncle Milty were around, he’d give it the GSOA.

—-

Scott, you use circular logic. Eventually you’ll have to meet head-on the arguments made by your opponents on the right.

19. July 2011 at 10:53

Scott, I think Greg is far too nice, but generally I understand what he’s saying, and what you are not responding too.

19. July 2011 at 17:23

“This is flat out wrong. All markets go up and down, even markets with no bubbles. Some day Australian housing prices will decline, but even then the Australian bubble predictors of 2005 will have been 100% wrong. Just as Greenspan was wrong in calling a stock bubble when the DJIA was 6400. No, that wasn’t a unwarranted level for the DJIA in 1996. I find it frustrating that any time a market falls the bubble predictors say they were right. Don’t people know that ALL VOLATILE MARKETS FALL ON OCCASION? It certainly doesn’t mean the market was a bubble before the fall. (Here I’m assuming bubble means EMH doesn’t hold.)”

Well, I would just say that it’s important to get into investor psychology and the dynamics of the market. The EMH may hold in a narrow sense that people act with regard to their present information and their incentives. In the case of the US housing bubble, most homebuyers had little equity in their homes and low teaser rates. Essentially if their home prices did not appreciate within two years (when the teaser rates ended), they would just walk away and offload their losses on the banks. The banks’ depositors could then offload their losses onto the government. Within each party’s incentives, the EMH holds even though the market created housing prices dramatically detached from fundamentals in many markets.

Same goes for imperfect information. The EMH may have held for Enron’s stock even though Enron was a house of cards because the shareholders could not realistically dig through their earnings numbers. Same may go for CDO buyers, who could not easily dig through the assets to figure out that many CDO’s became worthless if only 8% of subprime mortgages defaulted.

I don’t think we’re that divergent as we think. However I do think the classical, semi-strong EMH only applies in broad strokes over the long-term, but that behavioral factors in the market’s microstructure, i.e short-term incentives and imperfect information, can make a sizable difference just as sticky wages (another market imperfection) can make a sizable difference.

20. July 2011 at 08:12

Greg, Once again, as soon as I show you are wrong, you deny saying other theories had no causal mechanism.

Morgan, Glad you understand Greg.

Matt, You said;

“Well, I would just say that it’s important to get into investor psychology”

How can it be important to do something that can’t be done?

You said;

“The banks’ depositors could then offload their losses onto the government.”

False, less than 10% of losses were offloaded onto the government. The banks took huge losses.

Some of your other points may be valid, but don’t bear on my criticism of the view that Greenspan was right about the stock bubble. He was wrong. Here’s what Nick Rowe said today:

“Any fool can predict that the market in peanut futures will crash. Because almost everything that can happen will happen eventually. But unless you put some sort of date on that prediction, it isn’t worth anything.”

20. July 2011 at 12:25

Scott — gather, give the extensive evidence I’ve seen, that you don’t do so well on reading comprehension tests.

I did NOT say that other theories do not make efforts to supply causal mechanisms.

I said this:

1) YOUR description provided above was in fact a description, and you offered nothing more in what you said. You did NOT provide a causal mechanism, in what you wrote. And you didn’t.

2) Some efforts to provide causal mechanisms are explanatory FAILS — they are failed attempts or they are causally implausible, or they don’t fit the causal make-up of the phenomena. Example: from what we know know of genetics the Lamarkian mechanism of adaptation is an explanatory FAIL. Similarly, the “God did it” explanation for speciation and adaptation doesn’t fit the causal make up of the phenomena or the evidence across historical time — it invokes a miracle that does not account for most of the evidence, e.g. DNA evidence of gradual evolution and tree-like branching thru history.

So, once again, you are falsely ascribing statements to me I did NOT make, and you are dodging the points and facts and assertions I did make.

What’s up with that, Scott?

Scott writes,

“Greg, Once again, as soon as I show you are wrong, you deny saying other theories had no causal mechanism.”

20. July 2011 at 12:27

A claim I NEVER made — as I have REPEATEDLY pointed out to you.

Again, you “argue” by falsely ascribing views to me that I do not hold, and which I have CLEARLY stated otherwise.

What’s up with that, Scott?

Scott writes,

“no bearing at all on the whether the housing bubble triggered the recession.”

20. July 2011 at 12:31

Scott, what part of this sentence don’t you understand?

“The housing bubble was not the trigger of the recession.”

Really.

You don’t understand it when I say it — so how WOULD you translate that sentence?

Repeatedly you read those words and then tell all of your readers I believe the exact opposite.

How should I characterize THAT behavior?

20. July 2011 at 12:38

Scott, what part of this sentence don’t you understand?

“The ultimate cause of the boom / bust cycle is the systematic distortion of relative prices across time, unsustainably misdirecting labor and capital throughout the economy and across time — the artificial boom & inevitable bust in construction and construction employment was part of the instantiation of this pattern.”

I can help you with each word and comma, if you do feel you don’t get it.

20. July 2011 at 12:45

Scott, a description is not a causal mechanism.

If I say that strawberry production goes down in the winter because, as everyone knows, strawberry production is seasonally cyclical, I have NOT provided a causal mechanism explaining this descriptive fact about winter production, and this descriptive fact about strawberries and seasons of the year. I’ve simply provided two descriptions of the same descriptive facts, which remains causally unexplained.

It’s telling to me about how many economists think about “causation” that you do not seem to get this point.

20. July 2011 at 13:37

Scott, what part of this paragraph don’t you understand?

When I pull on an elastic volleyball net painted with stripes of color (indicated areas of more or less elasticity) — and I then let go of the net and it snaps back where it was (after gyrating around), the cause of movement of the net that has explanatory interest is the pulling on the net, and perhaps secondarily the properties of the net which make it gyrate.

The “pulling on the net” is the systematic distortion of relative prices, particularly relative prices across time (if you don’t know what those might be, just ask, Scott).

The different production processes of the net might be the different stripes of differing elasticity.

Did any _one_ of those stripes in _isolation_ cause the net to stretch and then snap back while gyrating?

NO.

And in isolation from the whole system and an outside ultimate cause, the colored stripes of netting didn’t set the whole thing in motion at all.

Again, the analogy here is between the different production sectors and different colored stripes on the net — and hence, analogously, between the construction sector and a particular colored striped on the net.

I await your mischaracterization of what I’ve written here, most likely an explication that says the exact opposite of my plainly spoken words. 😉

20. July 2011 at 16:18

Scott,

The “net” of the economy is “stretchy” because:

1) Rival production processes can take more or less time, but people will extend extend the time length of production processes only if it promises greater output. These choices are played off against all other marginal choice evaluations.

2. The quantity and flow and liquidity of money & credit & near monies changes over time, due to a number of factors.

3. There is non-transparency in the system — ESPECIALLY across the time dimensions of the system involving production & credit.

Nos. 1, 2 & 3 interact with each other dynamically — allowing the system to S T R E T CH across time & contrct across time.

The gyrating and catastrophic contraction leaves some part of the net without any tension — it leaves part of the net “unemployed”, flopping around without tension — until a new equilibrium of equi-tension is restored.

Wondering just how you can recast that in way that gets the insight and point completely backwards …

21. July 2011 at 07:17

Greg, So you don’t think the problem was too much capital directed into housing. Hmmm, so all those horror stories of the OC boom and bust in housing were what? Provided to entertain me?

22. July 2011 at 22:31

Scott,

The problem is misdirection of capital and labor _across_ the economy.

And this problem didn’t cause itself.

So, no, the problem isn’t just housing in OC.

Housing in OC is an easy to see and understand exemplification of the problem.

And it provides a dramatic exemplification of a pattern that demands explanation.

But ispt’s only a slice of the problem.

And there are causes behind this pattern.

Once aagain, your false choice “either / or” mirepresents my simple and plain words, which not come close to saying what you cast them as saying.

I’d suggest it takes more work for you to misrepresent me than it does to simply acknowledge and address the simple and plainly spoken points I am making.

Without your intentional misrepresentations, you’d have to honestly engage the most powerful explanatory rival out there.

But you’d prefer to punt with not even close to plausible mischaracterizations of my very plain and simple words.

22. July 2011 at 22:36

This is intentionally ambiguois, isn’t it?

The answer you well understand is that this is part of the problem, but only a part, and not the originating problem, as I’ve plainly said.

Scott writes,

“So you don’t think the problem was too much capital directed into housing.”

This isn’t that hard, Scott, and you are this dumb.

So what is up with this misrepresentation?

22. July 2011 at 22:36

aren’t

23. July 2011 at 11:53

Greg, But whenever I ask for evidence people point to housing. So where’s the evidence for other industries?

23. July 2011 at 19:51

Scott, I’m not an econometrician, much less a econ journalist.

However, another industry with production and labor drop off was the auto industry.

Economic data a not socially constructed using Hayekian econ as a the econtheory behind the constructuons, so this sort of thing isn’t something ready at had.

And grad students who work on the empirics of Hayekian macro don’t get hired.

So very little work is done on the topic.

All work done on the topic that I’ve see — cross industry & commodities, etc. — is supportive of the empirical patterns suggested by Hayek’s “model”.

23. July 2011 at 20:27

Scott, when you watch the tide come in at a little cove on the ocean, do you assume the only particles of water that are rising are the ones you personally are looking at?

24. July 2011 at 07:39

Greg, Autos don’t support the Austrian story at all. Sales fell in early 2008 due to high oil prices. But then oil prices plunged to very low level in early 2009, and auto sales plunged much more. Hayek would call that a secondary deflation.