Fannie, Freddie, and the three “crises”

There’s a lot of discussion now about the role of the GSEs in “the crisis.” Unfortunately, not everyone is talking about the same crisis. Some are talking about the housing bubble/crash, some are talking about the late 2008 financial crisis, and I believe both groups have the 2011 unemployment crisis in the backs of their minds (otherwise why is the debate seen as being so important?) After all, there is no similarly high-charged debate over the auto crisis/bailout/sales slump.

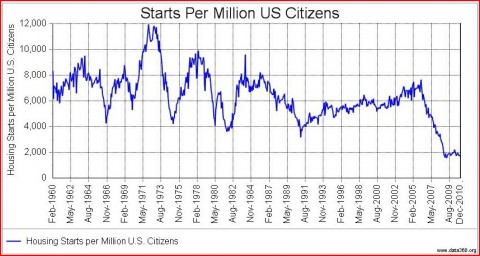

Let’s start with the housing crisis. A major theme of the Austrians is that too many houses were built in the mid-2000s, and the resulting slump has led to high unemployment. Here are US housing starts per capita going back to 1960:

As you can see, housing starts over the last decade have been far below the level of previous decades. We certainly don’t have a weak housing sector in 2011 because an extraordinarily large number of homes were built in the past decade. Rather it seems the recession has caused many families to double up. BTW, I will concede that we built too many homes in the mid-decade period, so I don’t completely deny the Austrian story. I just don’t think too many houses is the huge “crisis” most people are talking about.

Instead, it seems to me that both sides of the GSE debate tacitly accept that lax lending standards due to either:

1. deregulation and moral hazard causing banks to take excessive risks, or

2. the GSEs and other federal housing rules, regulations, tax breaks, etc.,

caused a housing price bubble in the mid-2000s. When this bubble collapsed, it created a severe banking crisis, which then led to a severe recession.

I believe this is mostly wrong. I’ll concede that part of the housing bubble was due to the factors mentioned above (both banks and the GSEs played a big role.) But the link between the housing bubble and the severe financial panic is much weaker than people realize. And the link between the severe financial panic and high unemployment in 2011 is almost nonexistent.

The mistake both sides make is to look for monocausal explanations. Here’s what the facts show:

1. The economics profession almost entirely disagrees with me. Yet in mid-2008 the consensus view of the economics profession was that we were NOT going to have a severe financial crisis and we were not going to have a severe recession. Indeed growth was forecast for 2009, along with moderate unemployment. And yet the scope of the subprime crisis was almost completely understood by that time.

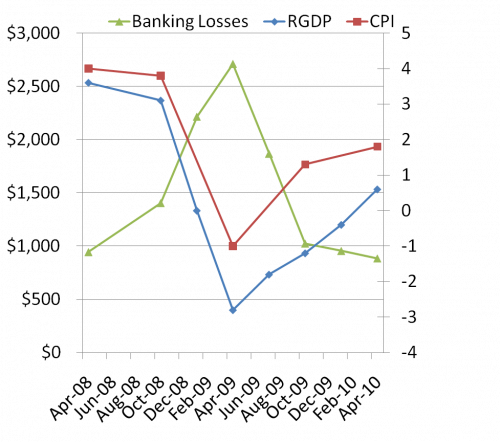

After things blew up, Bernanke was mocked for early statements suggesting that likely subprime losses, even in the worst case, were not large enough to bring down the US banking system. But of course he was right. Here’s what actually happened:

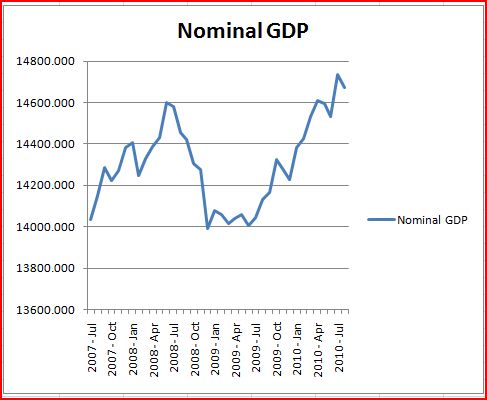

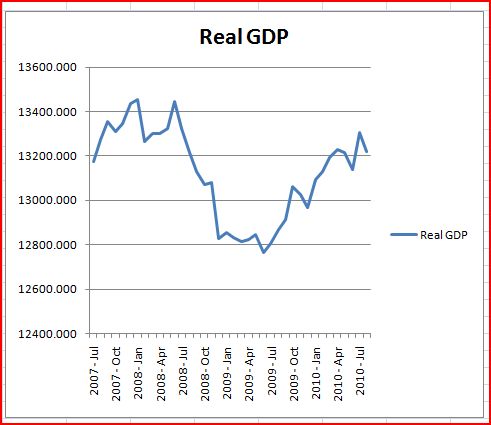

1. Between June and December 2008 both NGDP and RGDP fell sharply.

2. The cause of the fall in RGDP was the fall in NGDP

3. NGDP fell at the fastest rate since 1938 because the economy was already sluggish due to the housing slump, which reduced the Wicksellian equilibrium rate of interest. Ditto for oil and auto sales. Normally the Fed would cut rates enough to prevent a recession. But this problem coincided with a severe commodity price shock, which drove up headline inflation and frightened the Fed. They did not cut rates once between April and October, by which time the great NGDP and RGDP crash was nearly two thirds over.

4. The big NGDP crash dramatically reduced almost all asset values in the second half of 2008. About half way through this crash, the severe phase of the banking crisis started. This doesn’t mean the earlier subprime fiasco played no role. It did greatly weaken the system in 2007 and early 2008. So the GDP crash was imposed on an already weakened banking system. A cold turned into pneumonia. GDP fell even faster.

5. Estimated losses to the entire US banking system soared during this crash, and peaked in early 2009 at roughly $2.7 trillion, only a modest fraction of which were subprime mortgages. Then expected growth rates recovered somewhat, asset values partially recovered, and estimated losses to US banking fell back under a trillion. So the proximate cause of the financial crash was tight money which drove NGDP expectations much lower, although the earlier subprime fiasco certainly created an environment with a low Wicksellian equilibrium rate, making monetary errors much more likely. And of course when rates hit the zero bound (which by the way didn’t occur until the great GDP crash had ended in December!!) the Fed had an even more difficult time steering the economy.

6. To summarize, the severe financial crisis could not have caused the great GDP collapse, because monthly GDP estimates show it was half over before the post-Lehman crisis even began. But even if this view is wrong, there is not a shred of theoretical or empirical evidence linking the current 9.2% unemployment with the 2008 financial crisis. Theory suggests that if a central bank inflation targets, it drives NGDP. The Fed says it has the economy where it wants it (in nominal terms), and doesn’t think we need more inflation. When it did think we needed more inflation mid-2010 (when the core rate had fallen to 0.6%) it did QE2, which raised core inflation back up to roughly where the Fed wanted it. Of course (just as in mid-2008) commodity price inflation is distorting Fed policy, but that’s a problem attributable to the Fed, not the financial crisis.

This graph shows how IMF estimates of total US banking losses are inversely correlated with expected total inflation and RGDP growth in 2009 and 2010.

I see three separate crises. A “misallocation of resources into housing crisis,” a “federal bailout of banks crisis,” and a high unemployment crisis. Who’s to blame for each?

1. The private banking system and the GSEs both played a major role in causing too much housing to be built in the mid-2000s. The errors of the private banking system were due to both misjudgment (they did lose money after all) and bad incentives (moral hazard due to various government backstops.) Pretty much the same is true of the GSEs, although their role has always been a bit more politicized, and Congress must accept some blame for pushing them to boost the housing market. But this was a modest problem, as the first graph shows. It’s not the “real” issue that the left and right is debating so vigorously.

2. The GSEs are far more to blame than the banks for the bailout problem. And the banks most to blame are often smaller banks that made loans to developers, not the more famous subprime mortgages. Last time I looked the estimated losses to the Treasury from the GSEs was a couple hundred billion, from the smaller banks (i.e. FDIC–which is financed by taxes, BTW) was over a hundred billion, and the big banks was near zero (depending on how much they lose on Bear Stearns.) That’s all you need to know about where to apportion blame for the bailout crisis.

3. As far as the high unemployment crisis, the proximate cause is low NGDP, which means the Fed is to blame. Then we can apportion some blame to Obama for not putting more of his people on the Fed, and not doing it sooner. But ultimately we macroeconomists are to blame, as both the Fed and Obama take their lead from us. We were mostly silent on the need for vigorous monetary stimulus in the last half of 2008, and many have remained silent ever since.

The hero is the EMH, as markets warned the Fed that money was way too tight in September 2008.

In the history books it says the 1929 stock market crash triggered the Depression. After an nearly identical crash in 1987 had zero effect on GDP, we learned that was false. But it’s hard to blame historians for connecting a high profile financial collapse, with an economic collapse that was barely underway, and suddenly got much worse. Economists should know better.

Here’s the GDP data I referred to (from Macroeconomics Advisers):

Tags: Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac

16. July 2011 at 09:42

The first chart isn’t very convincing. Why would you expect housing starts to be proportional to the population in the first place? You might if the population were growing at a constant rate, but it wasn’t. The baby boomers reached adulthood in the 70’s and 80’s. After that the growth rate of the adult population declined. Back in 1989, based on the demographics, Mankiw and Weil made their breathtakingly inaccurate but still well-founded forecast that the housing market would weaken over the coming decades. We should at least have expected the rate of housing starts to decline — by how much is not immediately clear. The fact that we don’t see any dramatic break from the historical pattern until 2007 is evidence that too many houses were being built.

To be clear, I don’t actually believe that housing was being heavily overbuilt during the 2000’s, but in order to understand why residential building failed to decline earlier, you need to take into account the pattern of real interest rates and international capital flows. At a deep level, it was about a shift in international preferences toward greater patience and hence an increase in the demand for long-lived assets as assets, which offset the underlying trend in the demand for US housing services.

16. July 2011 at 10:27

Andy, I don’t have any problem with your comment, you’ll note that I did suggest too many houses were build in the mid-2000s. My point was that lots of lazy people simply say “look at all the houses we built.” Or “there was an orgy of home construction.” No there wasn’t–home construction has been strikingly low in the past decade. Now if one wants to argue it should have been lower for various demographic reasons, I’m fine with that. For instance, immigration slowed dramatically after the 2006 crackdown by the Bush administration, and some state governments. That’s another factor. But we know from previous severe housing slumps that these things don’t cause great recessions. Something else must be to blame. In addition, the big drop in housing construction actually occurred well before the big drop in RGDP (which was caused by lower NGDP.)

About 70% of the housing slump occurred between January 2006 and April 2008, and unemployment rose from 4.7% to 4.9%. I’m willing to attribute 100% of that increase in unemployment to the housing crash.

16. July 2011 at 11:34

I’ll say it again: All other economics bloggers and commentators: Please shut up, and run Scott Sumner’s blog in your place.

Crickey Almighty, no one else has as compelling an explanation of the Great Recession or policy solution.

Instead, the Fed is imitating the Bank of Japan, and we even run large fiscal deficits as they did. They have been zero-bound too. That approach has failed Japan. But hey–only for 20 years or so, and counting.

Tight money does not get you out of a long recession.

16. July 2011 at 12:25

Just like any other resource, when credit is tight, the price of credit (interest rates) should rise. Explaining the great depression and our current one with tight money fails to account for the fact that the two worst economic crises in our history saw the most active Fed policy while all the other slumps no one really remembers, like 1920-21 didn’t. If Fed tightness is the primary explanation, how come the days of the classical gold standard never saw anything as bad as today or the 1930s?

16. July 2011 at 12:42

By most active policy, I mean at the time of the crisis- 1929-31 and 2008-. During 29-31 in particular, the Fed ignored the previous line of thinking elaborated by Bagehot that during a financial crisis, the central bank should lend at a high rate of discount. That conventional wisdom had been successful overall. In contrast between 29 and 31 rates fell from 6 to 1.5. Let the market work and let the liquidations happen. Stop subsidizing bad businesses with cheap credit.

16. July 2011 at 13:13

Scott

Perfect post. Only comment, raised by Andy Harless. Better to use the Stock of Houses/Population (H/P) (I´ve sent you the graph via email). All through the 70´s and 80´s, the H/P ratio rose – from a little less than 34 to a little over 42 in 1989. From then on it stayed stable (“steady state level”). In 2001-02 there was significant net house destruction, so the so called “excess home building” in 2003-06 was just to regain the “steady state” stock of houses!

16. July 2011 at 13:15

Scott –

I enjoy your blog a lot, and while I’m no kind of monetary economist I find your explanations of the crisis satisfying. But there seems to be a piece missing. Namely, if falling NGDP caused the collapse in asset values that led to the financial crisis, and also led to the subsequent rise in unemployment, then *what caused the NGDP collapse*? The run on the shadow banking system was underway in late-2007, culminating in the collapse of Bear Stearns in March 2008, ie before the sharp drop in NGDP in mid-2008. I know that a lot of people put Lehman as the start date for the crisis, but that’s clearly not accurate.

In any case, it seems like the NGDP story needs an element that explains the drop in NGDP.

Maybe you’ve covered this previously, and I just can’t recall the post.

16. July 2011 at 14:48

Scott, I think you mis-state this because you don’t quite grasp the nuance:

“A major theme of the Austrians is that too many houses were built in the mid-2000s, and the resulting slump has led to high unemployment.”

The issue is NOT too many houses were built, that’s easy to solve, the folks who financed it all get GUTTEDLIKEFISH the houses sell for pennies on the dollar, rents go down – things are fine.

THE ISSUE: the wrong folks (the bankers) have not been forced into insolvency, they are still OWNING the houses.

Until they are GUTTEDLIKEFISH, and 12M houses go to the guys with cash paying next to nothing… the economy will suck wind.

People are living with each other, because there aren’t enough CHEAPASSRENTALS on the market – like there should be.

So please STOP showing that damn housing stock diagram, focus on the PROBLEM: the wrong people have the hard assets.

THE. WRONG. PEOPLE. HAVE. THE. HARD. ASSETS.

Please concern yourself with this fact, everything else will solve itself.

16. July 2011 at 15:27

Financed by taxes? That’s a flip remark. Yes, the structure of the FDIC premiums does not really match cost to risk, but at least we can say that the funds the FDIC has paid out were paid in by the banking industry and are ‘private’. So that tax is built into the price of every loan. That hardly puts it in the same class as the hundreds of billions that have been fed specifically into the GSEs.

16. July 2011 at 18:30

“…the link between the housing bubble and the severe financial panic is much weaker than people realize.”

Gorton does a great job of establishing that link. Lehman was one step in the chain of localized runs on shadow bank liabilities that began in Aug. 2007. Post-Lehman, these runs turned into a wider run on the non-deposit liabilities of the banking system.

The situation in 2007-2008 was quite unlike the Great Depression. In mid-Aug. of 2008, 5yr TIPS spreads were still at a normal level of 2%. Compare this to the lead up to the failure of the Bank of the United States in 1931, when prices were deflating steeply and real interest rates were punishingly high. The 2007-2008 financial crisis — caused by haircuts on AAA-rated collateral backing the non-deposit funding of the banking system — began well before the crash in NGDP expectations. Once those haircuts spread to the entire system’s liabilities, NGDP expectations crashed. This generalized run commenced after the GSE failures and culminated in the aftermath of Lehman.

The explanation for the widening of the crisis in the fall of 2008 has to do with market perceptions of the Fed Put. I believe you have written something on the order of, “the markets did not care about Bear’s failure.” Of course they didn’t: Bear’s creditors were bailed out in full. The meaning of the Bear bail out was that the Fed would not let any large firm’s creditors experience losses, and this quelled the problem of collateral haircuts for a time. This view began to change in Aug. 2008 as Fannie and Freddie’s preferred shareholders — quasi-creditors — were wiped out. It culminated in the decision to let Lehman’s creditors experience steep losses. At that point, the non-deposit liabilities of the banking system, collectively, became suspect, and collateral haircuts spiked.

In short, if you promise markets — even implicitly — a put, you better make good on it when the time comes. The Fed didn’t, and markets reacted by marking down the value of collateral backing large chunks of our banking system. Why didn’t the Fed make good on its put? That is an interesting question…

16. July 2011 at 19:05

Here are much more telling graphics.

Housing starts, under construction, and completed:

http://cr4re.com/charts/charts.html?New-Home#category=New-Home&chart=NHSInventoryMay2011.jpg

Unemployment by sector, number unemployed for each job opening:

http://www.time.com/time/interactive/0,31813,1974616,00.html

Unemployment by sector, job loss percentages:

http://crazybear.posterous.com/structural-shift-in-the-economy#!/slideshow

16. July 2011 at 19:20

I’d say it was a consumer debt bubble that kept mainfesting itself as various asset bubbles because most of the lower and middle class was suffering negative real earnings growth based on their budgets.

16. July 2011 at 19:24

“After things blew up, Bernanke was mocked for early statements suggesting that likely subprime losses, even in the worst case, were not large enough to bring down the US banking system. But of course he was right. Here’s what actually happened:”

No, bernanke should be mocked for not looking at more than subprime. Maybe if he would have gotten the firing he deserved and no one rehired him for anything (what he actually deserves) then maybe he would have defaulted on his own mortgage instead of whatever fix to it he did. If he can’t do personal finance, he should not even be in economics.

16. July 2011 at 19:31

Kindred Winecoff said: “Namely, if falling NGDP caused the collapse in asset values that led to the financial crisis, and also led to the subsequent rise in unemployment, then *what caused the NGDP collapse*?”

I’d say take a look at the amount of medium of exchange vs. the amount of available goods/services along with people’s budgets who aren’t rich.

16. July 2011 at 19:45

This is a really unscientific & erroneous explication of the causal mechanism at the heart of Hayekian macro:

“A major theme of the Austrians is that too many houses were built”

Especially if you look at this:

http://cr4re.com/charts/charts.html?New-Home#category=New-Home&chart=NHSInventoryMay2011.jpg

Also, housing size has exploded:

“The average American house size has more than doubled since the 1950s; it now stands at 2349 square feet.”

http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=5525283

The Hayekian causal mechanism takes into account a significant factual causal structure of the world missing from the rest of economic “science” — the competing relative time length of alternative production processes.

One of the longest production processes of all is the product produced by a house — the output of the typical capital production good we call a “house” can easily extend beyond a hundred years. And people borrow across 30 years to secure ownership of this production good.

16. July 2011 at 19:46

And as every economist should be able to tell you, the causal action happens at the margin ….

“The Hayekian causal mechanism takes into account a significant factual causal structure of the world missing from the rest of economic “science” “” the competing relative time length of alternative production processes.”

16. July 2011 at 20:05

John: If Fed tightness is the primary explanation, how come the days of the classical gold standard never saw anything as bad as today or the 1930s? Any Victorian knowledgeable in economic history would give a hollow laugh at that one. The 1890s Depression was even worse than the 1930s Depression in Victoria and was severe across the developed world (certainly worse than now, if not as generally as bad as the 1930s). It just did not lead to Hitler and World War, nor a collapse in world trade, so we do not remember it as dramatically.

It is also a well-established pattern than the sooner you left the gold standard in the 1930s, the sooner you recovered. If I was to nominate one reason why economists are generally not “gold bugs”, that would be a prime candidate.

16. July 2011 at 20:16

Here is a much more telling graphic, showing housing starts, under construction, and completed over the years:

http://cr4re.com/charts/charts.html?New-Home#category=New-Home&chart=NHSInventoryMay2011.jpg

Note well. Hayekian macro is not a mono-causal mechanism, it never looks at the production of any one product in isolation, and it evaluates malinvestment in terms of changes in the production of shorter or longer production process, it does NOT grab God’s Eye View judgments out the air unrelated to anything else .. or out of a historical time series correlating two physical variables, such as population to houses. Doing that — correlating two physical variables — is is not economic thinking, as I shouldn’t have to explain to anyone.

16. July 2011 at 20:44

In #5 Scott makes the statement “only a modest fraction of which were subprime mortgages.”

So what caused the majority of the $2.7 Million in losses to the US banking system?

16. July 2011 at 21:21

Lorenzo,

If the 1890s depression was so bad, quick, who was the president when it started? People point to the 1800s depressions as bad because they see deflation; this is meaningless because when increases in money supply were limited, productivity gains put downward pressure on prices. Often whatever GDP numbers you can dig up will show real GDP growth at levels we’d kill for today. Ive looked at the numbers and supposedly real GDP growth was over 6% during the 1870s which was America’s worst economy before the Great Depression. I challenge you to show any numbers indicating any economic crisis from 1800-1930 was worse than our current one or the Great Depression.

As far as leaving the gold standard, here’s the order countries severed their ties to gold: Germany, Britain (September), Japan (december 1931), US (1933), France (1936). Industrial output in 1937 relative to 1929: Japan, Britain, Germany, US, France. Weak correlation at best. Besides, if solving it was simply about leaving the Gold Standard, how come the depression lasted so long?

16. July 2011 at 21:35

As you can see, housing starts over the last decade have been far below the level of previous decades. We certainly don’t have a weak housing sector in 2011 because an extraordinarily large number of homes were built in the past decade. Rather it seems the recession has caused many families to double up.

Housing starts track new houshold formation much more closely than total population, and rate of household formation is very influenced by economic conditions, logically enough. There are big cyclical swings in both. Guess what’s going on now.

Out of curiousity a while back I ran the data for both back to 1960 and figured the running “inventory” of both. That is, a running tally of what cumualtive household formations and housing starts totaled, relative to long-term trendlines.

By my simple measure recent housing starts peaked with an inventory of 40% of an average year’s worth of starts above the trend line in 2007. That’s a cyclical high but a typical one. About the same or a little higher was reached in three other cycles since 1960.

But the plunge in starts since 2007 is unprecedented — by the end of 2010 cumulative starts were 72% of an average year’s worth of starts below trend. The next-lowest figure was 46% below trend back in 1970. If things were “normal” this would predict a huge boom in housing starts soon.

But housing starts are *following* household formation, which is plunging even faster, like an ICBM heading straight to its target.

In 2007 household formation was 1627k (average 1998-2007: 1499k) and housing starts were 1355k (average 1998-2007: 1716k). In 2010 household formation was all of 357k, down 78% from 2007 and down 76% from the prior ten year average. Housing starts were 587k, down 57% from 2007 and down 66% from the prior ten years. That’s a big fall, but it is still *well behind* the fall in household formation.

If I still had my blog I’d post the graphs — the line for household formation is heading straight down like to the bottom of the sea, it’s three times the fastest-deepest decline of the last 40 years. The line for housing starts looks like it is just striving to not fall too far behind.

Short term: I see no hope of housing starts picking up until some time after household formation reverses — and that’s not going to happen until after the economy picks up. The people who say “the economy won’t pick up until housing does” have it backwards.

Long term: Buy the stocks of the big homebuilders who have survived all this to date, strengthened their balance sheets, and are buying land for future development cheap. At *some* point the home building industry has to come roaring back. The inventory shortage has to be over a full year’s worth by now compared to long-term trend, and is still growing. That’s more than twice the biggest shortage compared to trend of the last 50 years. Buy cheap and hold. Long term. Maybe really long.

By my simple measures. FWIW.

16. July 2011 at 21:40

There was NO classical gold standard after 1914.

As _everyone_ at the time understood.

As MASSIVE mistakes were made attempting to restore the classical gold standard — which was NEVER successfully restored. Parties at the time were well aware of this — it was common knowledge that everyone was still OFF the classical gold standard.

The idea that nations were getting “off” the classical gold standard in the 1930s is brain dead — no there wasn’t a classical gold standard in the period 1914-1936, and so it was impossible for any nation to get “off” the classical gold standard.

That had already happened in 1914 …

WAKE UP people. Learn some history of economics — something the vast majority of economists NEVER learn.

16. July 2011 at 21:43

I’d like to add that “gold bugs” have made a lot of money over the past 10 years. The reason most economists today aren’t hold bugs is because governments dislike gold; it ties their hands. Since schools want their Econ graduates to land prominent jobs like head of the Federal Reserve, or to win government funded research grants, they’re unlikely to teach economic views that aren’t popular with the government; it wouldn’t be in their self-interest. I agree that the gold standard wouldn’t work today when everyone expects and desires inflation, the problem is that people have different prices in mind when they want inflation. One guy benefits from stocks rising, another gold, another oil. The problem is that most end up as losers in the end.

16. July 2011 at 21:44

This cycle has happened several times in Southern California in the last 4 decades:

“Long term: Buy the stocks of the big homebuilders who have survived all this to date, strengthened their balance sheets, and are buying land for future development cheap. At *some* point the home building industry has to come roaring back.”

Example, William Lyon Homes has made huge fortunes and has been on the brink of bankruptcy more than once, in a cyclical pattern following the big peaks and valleys of the SoCal housing market.

16. July 2011 at 23:24

David Pearson’s reference to Gary Gorton’s analysis of the run on the shadow banking system is 100% on target. It seems that Scott would benefit from reading up on this.

17. July 2011 at 02:55

[…] is to blame for the unemployment crisis? (The Money Illusion via […]

17. July 2011 at 05:35

Scott,

The median home price increased from 150M in 1998 to almost 275M in 2006. If you look at the historical trends of home prices, this is an unbelievably rapid increase. To what do you attribute this statistic and what part does this play in your narrative?

17. July 2011 at 05:51

John, You said

“Just like any other resource, when credit is tight, the price of credit (interest rates) should rise. Explaining the great depression and our current one with tight money . . . ”

You are confusing money and credit, a very common mistake. The Fed controls the price of money, markets control the price of credit.

marcus, Thanks, but are you sure that graph is accurate? Perhaps they switched to a different statistical technique in 2002. I’m sure there wasn’t “net house destruction.”

Thanks Kindred, In the post I said the severe phase of the financial crisis began after Lehman failed. I agree that a milder crisis started in 2007, but even in mid-2008 it wasn’t severe enough to lead to expectations of recession.

It’s very difficult to explain to people how tight money caused NGDP to fall in late 2008, because for tight money to happen, the Fed does not have to do anything. It’s enough for the Fed to be passive when the Wicksellian equilbrium rate is falling. That’s the rate which provides a stable macro environment. Because there was less demand for houses and cars than usual in 2008 (housing bust, high oil prices) credit demand was also falling. In that environment the Fed needs to cut rates sharply to prevent recession. During the time when the Fed needed to do this (April to October 2008), it did not cut rates once–it was worried about inflation.

Morgan, But you are buying into the false Austrian story that housing is the key to the recession.

Jon, You said;

Yes, the structure of the FDIC premiums does not really match cost to risk, but at least we can say that the funds the FDIC has paid out were paid in by the banking industry and are ‘private’. So that tax is built into the price of every loan. That hardly puts it in the same class as the hundreds of billions that have been fed specifically into the GSEs.

I consider the gasoline excise tax to be a tax, not a fee paid by oil companies. I believe that is standard. So why isn’t an excise tax on bank deposits also viewed as a tax?

David, You said;

“The situation in 2007-2008 was quite unlike the Great Depression. In mid-Aug. of 2008, 5yr TIPS spreads were still at a normal level of 2%. Compare this to the lead up to the failure of the Bank of the United States in 1931”

I agree, but that’s not the comparison I make. I compare the severe phase of the cycle to the Depression. Look at the graphs, the severe phase was the second half of 2008. Mid-2008 was like 1929. In both late 2008, and in the Great Contraction, the severe financial panic occurred DURING the economic contraction, and was mostly caused by the economic contraction. If NGDP grew 5% in 2008, does anyone seriously think the US would have had a severe banking panic in late 2008?

I agree that the differential treatment of Bear and Lehman was a huge factor in the run on the banking system in late 2008. I see weak NGDP as a necessary condition, but not sufficient. It’s very possible that the non-bailout of Lehman (which I wrongly supported at the time) was also a necessary condition.

Greg, You said;

“Here are much more telling graphics.

Housing starts, under construction, and completed:”

No, those stats don’t show what you claim, they are stock variables. Housing starts are a flow variable. And second, they don’t support the Austrian story at all. Inventories rose because of the recession.

As far an unemployment, let me ask you this. If the unemployment rate for beekeepers was 50% (higher than any other group) would you blame the recession on beekeeping?

Second, only a fraction of the construction workers who are unemployed worked in residential construction.

Fed up, I have problems with Bernanke, but for other reasons.

Greg, You said:

“This is a really unscientific & erroneous explication of the causal mechanism at the heart of Hayekian macro:

“A major theme of the Austrians is that too many houses were built””

I’m just reporting what I hear Austrians talking about all the time (internet Austrians). I stand by my comment.

Lorenzo, He’s also wrong about interest rates, which tended to fall during recessions even before the Fed existed. That’s because interest rates are set by the market. In 1930 the Fed actually slowed the fall in interest rates from free market conditions.

Andujar, I think the IMF has the data in their April 2009 report, but I don’t recall right now. Certainly non-subprime mortgages, loans to developers, commercial loans, industrial loans, etc, were also big factors.

John, There is an extremely strong correlation between when country left the gold standard and when they started recovering. I believe Japan left before the date you indicated.

Jim Glass, Very good point. Is there a graph you could email me? If not, I’ll try to find it and do a post.

Greg, There was also no “classical gold standard” before 1914.

John, I’ve made more money than the gold bugs.

Glibfighter, See my earlier response to David.

17. July 2011 at 06:21

Scott, where is your data coming from showing that “only a fraction” of those unemployed in construction are from residential home construction?

17. July 2011 at 06:37

Scott

If you are right about Bernanke’s mistakes in the summer of 2008 causing the great recession it has two ironic implications. First, it means Bernanke did exactly what he promised Friedman not to do. Secondly, it means Cramer was the sanest voice at the time:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOVXh4xM-Ww&feature=youtube_gdata_player

I’m also glad to hear you’ve made more money than the gold bugs.

17. July 2011 at 07:15

From an Econlog commenter named Chris Koresko:

Chris Koresko writes:

Scott Sumner: It’s awkward to try to criticize the ideas of someone who is obviously more deeply knowledgeable than myself, but I am moved to do so by what amounts to a gut feeling that this story is focused too much on the measurable quantities (NGDP, RGDP, etc) at the expense of poorly-measured, but potentially more important, factors.

My sense is that we are suffering from a series of related policy blunders, all of which were efforts to expand government control over the economy.

The push to expand homeownership was one of these. Never mind the rate of housing starts per unit population; what matters for this argument is the amount of wealth flowing into the housing market, and the degree to which that wealth was well-invested. Policy changes resulted in a lot of people living in homes they couldn’t really afford, and because their loans were non-recourse, the error was corrected at the expense of the lenders, and ultimately of the financial system.

Then there was a federal push to keep delinquent borrowers in their homes via “loan modifications”, which tended to involve government arm-twisting of creditors into abandoning some of their property rights. Something similar appears to have happened with the big auto bailouts, with the President himself publicly scolding Chrysler’s secured creditors (whom he referred to as ‘speculators’) for demanding that they be paid their due according to the law.

The legal security of property rights is acknowledged by the Washington Consensus as a key factor in economic growth for developing countries. Would it be surprising if a pattern of violations of it by Washington itself had an adverse impact on the U.S.?

Then there was a set of policies which drove up the cost of labor, including a rather large increase in the minimum wage, regulatory changes to make it easier for employees to sue their employers, and the Affordable Care Act which is the “devil we don’t know” because a lot of it is implemented in as-yet unwritten regulations. Since these policies (I think… correct me if I’m wrong) raise the cost of labor by an amount which is larger as a percentage of the total for lower-wage workers, their effect is to preferentially increase unemployment at the low-wage, low-education end of the labor market. This is the pattern we have in this recession.

On top of that there is a complex new set of financial regulations (I’m talking mostly about Dodd-Frank here) for which apparently no one in the government has attempted to assess the cost to business (according to Congressional testimony… sorry, my memory is vague as to who gave it). And it’s apparently created a whole new set of offices with new regulatory powers, while apparently making no effort to rein in Fannie & Freddie. The latter omission makes it look like the government is content to allow those institutions to continue operating more or less as they did when they helped cause the housing crash; in fact, the President himself has called for a strengthening of the CRA.

At the same time the executive branch has started unilaterally granting Affordable Care Act wavers to specific organizations, despite (as I understand it) having no legal authority in the Act to do so. And then it turns out that a substantial percentage of those waivers went to businesses in the district of Nancy Pelosi, the former House Speaker who was instrumental in getting the Act passed, and another large fraction to labor unions who also pushed for it.

Meanwhile the federal government has been throwing around trillions of dollars based on planning which appears haphazard at best. There was most of a trillion in TARP, which was billed (if memory serves) as a way to rescue “too big to fail” financial institutions by buying toxic assets, but turned into a kind of slush fund. Some of that was lent to banks that didn’t need the money and repaid it. The TARP law required that the repaid funds go back to the treasury, but some of them got spent anyway… correct?

Then there is the Treasury, which has been making trillion-dollar-class moves with euphemistic names (“quantitative easing”). Almost no one outside Treasury seems to understand what is going on, and it’s worrisome.

And of course there is the ‘stimulus’, which passed on an almost purely partisan vote and was billed as a means to kick off ‘shovel-ready’ projects across the country, but turned out to be mostly short-term tax cuts and grants to keep state governments from having to make budget cuts for a year or two. And multi-billion dollar projects that were in no way ‘shovel-ready’, but would take years or decades to complete. And there were scandals associated with it, involving jobs ‘created or saved’ in non-existent zip codes and the like. In the end, the ‘stimulus’ money spent on new construction projects in the first couple of years was what, a few percent?

And throughout all of this was the prospect of a big income tax increase coming with the expiration of the Bush-era cuts, initially in 2010 and now delayed a couple of years… maybe.

The President has been all over the place on taxes, campaigning with the promise of a middle-class tax cut and promises that there would be no tax hikes of any kind. At times he has advocated a reduction in the corporate tax rate. Lately he’s refusing to accept any deal on the debt limit that doesn’t include a tax increase, and has been railing against the rule changes for taxation of corporate jets which were put into place by the ‘stimulus’ law.

On top of all this, it appears to be U.S. policy to choke off its own energy supply. We’ve seen the ban on drilling in the Gulf that persists despite the order of a federal judge; new moves that will force the closure of many coal-fired power plants; an expressed desire on the part of our Energy secretary to see gasoline prices reach European levels; and the beginnings of a regulatory regime for carbon dioxide, despite the refusal of Congress to authorize it.

Meanwhile the federal debt is growing at an alarming rate, and it’s not hard to see that we are in for some combination of massive spending cuts, massive tax increases, and federal default, in the near future… years, not decades. The politicians are disunited and intransigent. Apparently the only detailed plans to deal with this, like Simpson-Bowles and Ryan, are off the table.

So the bottom line is that federal economic policy is in shambles, growing less coherent and more destructive as the government itself grows larger and more powerful. And the people who matter recognize this. Surveys show very little optimism on the part of the entrepreneurs who produce essentially all net U.S. job creation. A recent study (by Tyler Cowen if memory serves) shows pretty conclusively that employment depends on private (not government) investment spending.

So I think that looking at NGDP and monetary policy at this point is not going to give you a good sense of what’s happening. The real drivers are not easily quantified, and are not the kind of things that show up in a macro textbook model. It’s no surprise to me that the modelers are being repeatedly surprised by how poorly the economy is doing lately.

17. July 2011 at 07:26

“That’s all you need to know about where to apportion blame for the bailout crisis.”

Well, isn’t it hypothetically possible that the Fed could be doing “under the table” bailouts of the banks, particularly by having the GSEs assume losses that ought to be of the banks. I do seem to remember some allegations that the GSEs were not pursuing claims against the banks as hard as they could. (Because, hey, the feds are bailing them both out, so why waste time arguing?)

“This cycle has happened several times in Southern California in the last 4 decades”

Yes, but that’s something exacerbated by the various growth-management and zoning control schemes adopted in Southern California. Even just a lengthy permitting process is bad for creating more peaks and valleys– you’ll get more construction done when it’s obvious that prices are already declining (because everything finally made it through permitting) and you’ll get a lack of construction at the beginning of booms (because things have to get through permitting.) It definitely exaggerates the cycles, as a quick comparison of growth-management states to non growth-management states will reveal. (And Arizona and Florida foolishly adopted growth-management to try to slow down their internal in-migration and housing growth, but it really just fueled the bubble.)

17. July 2011 at 07:31

“Easy pickings”. From David Leonhardt at the NYT:

“We are living through a tremendous bust. It isn’t simply a housing bust. It’s a fizzling of the great consumer bubble that was decades in the making”.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/17/sunday-review/17economic.html?_r=1

17. July 2011 at 09:02

Scott,

NGDP expectations doubtless played a role after Lehman. I disagree with you on the timing before then.

You write that, “Mid-2008 was like 1929.” But in August 2008 there was no discernible crash in NGDP expectations. Inflation expectations were normal after coming off of a cyclical peak. The stock market had experienced a mild correction (around 8%) for the year. Many saw the decline in commodity prices from abnormal levels as a positive for the economy. The Fed seemed the be willing to step in to prevent any kind of broad financial crisis.

Further, Lehman was a process, not an event. Worries about Lehman’s balance sheet surfaced right after Bear — it was the logical next candidate for failure. As it turns out, Erin Callan, the Lehman CFO, would later be accused of doctoring Lehman’s 2q08 results in an effort to make the balance sheet look better and thus stem the tide of concern. The only thing standing in the way of a run on Lehman in the months after Bear was this fraud and the implicit Fed put.

The 2008 NGDP expectations crash and culmination of the financial crisis were roughly contemporaneous. Europe offers a useful analogy today. If Italy experienced a run on its banking system next month, along with a stock market crash, would we say the crisis began in August 2011, or much earlier with broad concerns over periphery sovereign debt?

17. July 2011 at 09:28

“But the link between the housing bubble and the severe financial panic is much weaker than people realize. And the link between the severe financial panic and high unemployment in 2011 is almost nonexistent.”

I’m a bit mystified by this statement as the connection seems obvious if one looks at the leverage employed against the housing market. Lehman, for instance, was levered 40-1, and such leverage was common place among the large banks. Then you add to that the CDS marketplace, which required minimal to no collateral – and you have a direct connection between the housing marketing and the financial panic. Housing goes down, which triggers CDS and margin calls, and the banks are forced to sell other assets to make those calls. And they don’t have the capital to begin with. Then, an old fashion run on the banks happens as people (and particularly other businesses) pull their money. Market starts to tumble which causes cascading selling. There’s the connection.

As for the second claim – that there is no link between the finanical panic and high employment, you’re forgetting the basis of rising GDP and consumer spending during the 2000-2006 period – mortgage equity extraction. The growth in the economy was illusionary and based on debt. We know, for instance, that wages for most mid and low income people were flat, and that they augmented this gap by using their house as an ATM. This money drove the economy during that period – but it obviously relied on housing continually going up. Once housing started going down, this triggered the financial crisis, which in turn shut down the ability of the consumer to extract cash from their house. In addition, with credit in general freezing up during the crisis, credit cards started tightening down on the consumer. All this leads to less money in the economy and the economy shrinks. Shrinking economy leads to people being laid off due to lack of demand. Now, we’re in a period of wages being lowered and credit is much tighter – so demand continues to be light – thus unemployment remains high.

“Indeed growth was forecast for 2009, along with moderate unemployment. And yet the scope of the subprime crisis was almost completely understood by that time.”

I’m not sure how you get to that – certainly the Fed had some idea of what the exposure was in terms of the total value of the sub-prime marketplace, but they had no idea and no transparency into certain financial instruments (CDO/CDS exposure), and they had no idea how levered some of these banks were. Indeed, Lehman was moving assets on and off their balance sheet to make their leverage appear less extreme. The Fed also likely had no view at all into AIG since it wasn’t even considered by the Fed – they were surprised by it. Bottom line, the Fed clearly did not recognize the scope of the crisis – and, more specifically, did not see the connected instruments and exposurers at the time.

“As far as the high unemployment crisis, the proximate cause is low NGDP, which means the Fed is to blame. Then we can apportion some blame to Obama for not putting more of his people on the Fed, and not doing it sooner. But ultimately we macroeconomists are to blame, as both the Fed and Obama take their lead from us. We were mostly silent on the need for vigorous monetary stimulus in the last half of 2008, and many have remained silent ever since.”

While I agree with you somewhat about the need for more stimulus – what more could the Fed have done in terms of stimulus in 2008 that it wasn’t already doing? In this case, I actually blame the government for not putting together a stimulus that matched the size of our economy – $1 trillion against an economy our size is like throwing some pebbles in a lake – especially when 40% of the stimulus was in the form of tax cuts. One additional small point, Obama has been trying to fill the Fed bench for some time – and has been blocked by Republicans.

17. July 2011 at 09:48

@ Benjamin Cole

You: “I’ll say it again: All other economics bloggers and commentators: Please shut up, and run Scott Sumner’s blog in your place.”

This is what I did: http://coffeehouse-economics.blogspot.com/2011/07/sumner-is-back-and-rocks-boat-amv.html

17. July 2011 at 10:01

Scott, this is simple.

The CAUSE is the changing time length / structure.

Many things make that up Many.

You don’t get it. Here’s why.

You don’t want to get it.

You want your own false and non-comorehending explication to stand in as a strawman so you can ignore the 800 lb gorilla in the room.

Do scientists in any other field pick up their knowledge base from “things they hear on the internet” — and then report them as as accurate representations of scientific conceptions — when what they write is clearly confusion and incomprehension.

Would a real scientist feel good about that?

Here is an apexample of where you show no understand of the causal mechansim at play in Hayek’s time structure of production macro. The unemployment and the bust in any sector is a consequence of the causal mechanism, not the source.

It’s bad form for a scientist to go around spreading false information and false and erroneous accounts of rival scientific theories — why do you do it?

“As far an unemployment, let me ask you this. If the unemployment rate for beekeepers was 50% (higher than any other group) would you blame the recession on beekeeping?”

17. July 2011 at 10:08

The geometrically larger percentage size of unemployment in some sectors as comoared with others is trace data to be explained.

The time structure distortion / malinvedtment causal mechansim accounts for this remarkable patterned whcih demands explanation.

Scott’s theory? … Not to much.

17. July 2011 at 10:09

compared = comoared

17. July 2011 at 10:38

Scott,

The Hayek causal mechanism involves the unsustainable distortion of the time structure of the economy – malinvestment in the domain of production processes taking more or less time. Anything that can produce false price signals can produce this unsustainable distortion.

A consequence of the collapse of an unsustainable distortion can be the collapse of near monies — shadow money:

http://hayekcenter.org/?p=2954

The business cycle produces striking patterns that demand systematic causal explanaton.

The dramatic boom & bust cycle in housing, commercial construction, and construction unempoyment is one of those things that demands explanation. This patterns is an explanadum, NOT an explanans.

No one who competently explicates the Hayek causal mechanism gets this backwards.

You have. Which means you are talking words but not communicaton any sense on this topic.

A RED flag is waving. A genuine scientist — the kind who don’t trade in BS — would take heed of the flag.

17. July 2011 at 10:41

Scott,

At the very least, you recognize a difference between a gold exchange standard and a gold bullion standard, right?

17. July 2011 at 12:03

To clear up the debate over Japan leaving the gold standard, the reattached their money to gold from 1930-31. Some ignore this period and list them as the 1st to leave it. But if you google it, officially they left in 31. But in the bigger picture, the gold standard really ended with WWI as Greg pointed out.

17. July 2011 at 12:13

marcus nunes post said: “”Easy pickings”. From David Leonhardt at the NYT:

“We are living through a tremendous bust. It isn’t simply a housing bust. It’s a fizzling of the great consumer bubble that was decades in the making”.

http://www.nytimes.com/2011/07/17/sunday-review/17economic.html?_r=1”

CR has this too with a graph.

http://www.calculatedriskblog.com/2011/07/leonhardt-were-spent.html

From NY Times article:

“If you’re looking for one overarching explanation for the still-terrible job market, it is this great consumer bust.”

And, “In past years, many of those customers could have relied on debt, often a home-equity line of credit or a credit card, to tide them over. Debt soared in the late 1980s, 1990s and the last decade, which allowed spending to grow faster than incomes and helped cushion every recession in that period.”

So were lower interest rates about tricking the lower and middle class into taking on more debt, which created a consumer debt bubble? Plus, I don’t believe rich people were going into debt because they didn’t need to.

“Earlier this year, Charles M. Holley Jr., the chief financial officer of Wal-Mart, said that his company had noticed consumers were often buying smaller packages toward the end of the month, just before many households receive their next paychecks. “You see customers that are running out of money at the end of the month,” Mr. Holley said.”

Budget problems for the lower and middle class. I bet “mr. cfo” does not have this problem.

“Surveying hundreds of years of crises around the world, Ms. Reinhart and Mr. Rogoff conclude that debt is the primary cause and that the aftermath is “deep and prolonged,” with “profound declines in output and employment.””

By debt, I’ll say both gov’t debt and private debt. So why does almost everyone insist that all new medium of exchange has to be the demand deposits from a loan/bond/IOU (making it debt)?

Page 2 is not very good.

“The easy thing now might be to proclaim that debt is evil and ask everyone “” consumers, the federal government, state governments “” to get thrifty. The pithiest version of that strategy comes from Andrew W. Mellon, the Treasury secretary when the Depression began: “Liquidate labor, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate,” Mellon said, according to his boss, President Herbert Hoover. “It will purge the rottenness out of the system.”

History, however, has a different verdict. If governments stop spending at the same time that consumers do, the economy can enter a vicious cycle, as it did in Hoover’s day.”

I reject the idea that do nothing and more gov’t debt are the only solutions.

“A more promising approach could instead offer a tax cut to businesses “” but only to those expanding their payrolls and, in the process, helping to solve the jobs crisis.”

IMO, it is a retirement crisis. Put some more people into retirement, and that will fix the unemployment crisis.

17. July 2011 at 14:01

[…] Source […]

17. July 2011 at 14:17

Scott, NON-RESPONSIVE.

I say you don’t understand the real Austrian issue – the HARD ASSETS are still in the wrong hands.

You have to respond by saying WHY that isn’t what matters. And that’s a full post out of you.

You saying this… “Morgan, But you are buying into the false Austrian story that housing is the key to the recession.”

It is totally illogical, its just you restating your opinion, not responding to the REAL point Austrians make.

We want to see the bankers LOSE, and not lose the way you pretend they do, I’m talking BANKRUPTCY / INSOLVENCY – we want to see 12M houses sold for $1+ auctions.

If you aren’t going to give real answers to your opponents, SAY SO.

17. July 2011 at 15:21

Why do people feel the need to lie about Hoover?

“If governments stop spending at the same time that consumers do, the economy can enter a vicious cycle, as it did in Hoover’s day.”

I think this tells us something very important about those who are spreading this lie about Hoover.

17. July 2011 at 15:58

Pete, I did a post about a year ago that links to some data. Lots of the unemployed construction workers are from commercial construction, infrastructure construction, etc.

Mattias, I’ve thought of that many times. I saw Cramer exactly one time in late 2008, and he was making a lot of sense. He was claiming central bank passivity was wrecking the stock market, and he was right. In the few times the central banks seemed to respond, stocks rose strongly.

Yancey, Your friend said;

“Never mind the rate of housing starts per unit population; what matters for this argument is the amount of wealth flowing into the housing market, and the degree to which that wealth was well-invested.”

Wealth doesn’t flow into markets. Markets are where transactions occur–each purchase is a sale.

In this blog I’ve been highly critical of many of the things he mentions, including the big minimum wage jump and Dodd-Frank. But those didn’t cause NGDP to collapse.

BTW, the Fed does QE2, not the Treasury.

John, I suppose the GSEs might have helped the big banks a bit, but they are losing hundreds of billions, so I still think they were almost certainly much worse than the big banks.

Marcus, As soon as you said NYT, I knew it’d be middle-brow pablum.

David, I will agree that NGDP expectations fell faster after Lehman than before, but they were certainly falling before. The day Lehman failed NGDP was barely above the level of early 2008. The real economy suddenly started getting much worse in August and September, and I’d guess that reduced asset values in their portfolio. In any case the further decline in NGDP (after Lehman) made things much worse. Recall that even immediately after Lehman the Fed didn’t even think we needed a quarter point cut–the economy got worse continually over a number of months, first slowly, then faster–that made the financial system get worse and worse. Every time the Fed’s tried to bail it out, the problem seemed to get worse. It was because they weren’t stopping NGDP from falling.

You asked:

“If Italy experienced a run on its banking system next month, along with a stock market crash, would we say the crisis began in August 2011, or much earlier with broad concerns over periphery sovereign debt?”

We’d say it began years earlier with NGDP falling 10% below trend. Then a recent slowdown in world growth was the last straw.

inthewoods: you asked;

“While I agree with you somewhat about the need for more stimulus – what more could the Fed have done in terms of stimulus in 2008 that it wasn’t already doing?”

A good place to start would have been to NOT ADOPT A HIGHLY CONTRACTIONARY POLICY LIKE INTEREST ON RESERVES IN OCTOBER 2008. How about cut interest rates at the September meeting, instead of holding them at 2%? Many people believe the Fed was restricted by the zero bound–not true, rates didn’t fall to zero until the GDP crash was already over in December.

Regarding the housing bubble your mistake is to assume the entire 30% crash in housing prices was inevitable as of 2006. In fact much of the decline was due to falling NGDP expectations, the very thing that triggered the financial crisis.

As for what drives NGDP, it is monetary policy, not consumer spending. The people in Zimbabwe were broke when their NGDP rose at a billion percent.

Thanks AMV.

Greg, You said;

“It’s bad form for a scientist to go around spreading false information and false and erroneous accounts of rival scientific theories “” why do you do it?”

How is that false? You sent me a link that showed the unemployment rate for construction workers was higher than for any other category. I presume you thought that was somehow meaningful. I simply asked if it would be important in beekeepers had an even higher unemployment rate. The unfortunately truth is that the graphs you send me rarely support your argument, indeed they often support mine.

What might be interesting is the fraction of all unemployed that are residential construction workers, not all construction workers.

The gold standard countries did not follow the rules of the game before WWI, and they continued to not follow the rules after. That’s what matters.

John, What matters is whether Japan devalued in late 1929.

Fed up, Having people retire would make things worse. We need more people working, not less!

As far as the NYT blaming the recession on less consumer spending, all one can do is shake one’s head, and hope someday they’ll stop confusing cause and effect.

Morgan, OK, get assets into the “right hands,” I have no objection. But that’s got nothing to do with the recession.

17. July 2011 at 15:59

Greg, Finally we agree on something–Hoover.

17. July 2011 at 17:08

“Regarding the housing bubble your mistake is to assume the entire 30% crash in housing prices was inevitable as of 2006. In fact much of the decline was due to falling NGDP expectations, the very thing that triggered the financial crisis.”

It was in 2006 if you were listening to the right people. I, for instance, had been talking about a collapse in housing prices starting in 2005.

“As for what drives NGDP, it is monetary policy, not consumer spending. The people in Zimbabwe were broke when their NGDP rose at a billion percent.”

Wait, are you saying that consumer spending, which accounts for 70%+ of total spending has no effect on GDP, and that monetary policy, alone, drives NGDP? That makes no sense to me – please explain how NGDP is completely divorced from consumer spending.

17. July 2011 at 18:00

Scott,

“I simply asked if it would be important in beekeepers had an even higher unemployment rate. The unfortunately truth is that the graphs you send me rarely support your argument, indeed they often support mine.”

When you get the other guy’s causal mechanism completely wrong and when you ascribe views he doesn’t hold — what you say may erroneously appear to be the case. But it depends on the getting things wrong part.

When this happens no-stop, I begin to suspect it is not an accident.

What part of this don’t you understand, Scott, because it seems simple to me, yet you seem actively to not to want to get it:

The geometrically larger percentage size of construction unemployment is an explanadum pattern that demands explanation.

IT’S NOT THE EXPLANATION.

The Hayek macro mechanism involves TWO key elements (for our purposes here.)

ONE. Shifts across ALL sectors and ALL production processes in the time dimension of production.

TWO. Rises and falls in the size of highly liquid near moneys and in the the demand for money stocks.

Housing, commercial construction, etc. are implicated in the Hayek causal mechanism only as a _part_ of the value structure through which the causal process works its way.

It’s a MASSIVE distortion and a MASSIVE failure of understanding to spin this as “housing _caused_ the recession as a isolated, single, mono cause.”

I haven’t said that because THAT IS NOT WHAT THE THEORY SAYS. And this is not what the causal mechanism assumes.

My assumption is that you _chose_ not to understand Hayek’s work, and that you chose to mischaracterize that work, and that you chose to micharacterize the application of that work to contemporary events, and you chose to mischaracterize the relation of patterns in the data to that explanatory mechanism.

Otherwise, you would stop ascribing the “Austrian” theory to stuff in ways your have been told repeatedly are erroneous — when you have no need to bring this rival causal explanation in at all.

You cast the Hayek mechanism falsely, then use that false explication as a stand in straw man to serve other rhetorical purposes.

Why?

If you had any interest in doing what scientists in other fields are careful to do — getting stuff right — you’d make the effort to avoid getting the science completely wrong.

The fact that you don’t make the effort indicates that you’ve thrown the pretense of behaving like a scientist out the window when it comes to engaging the science here.

The techniques of the politician will serve your rhetorical purposes better, as far as you are concerned.

Of course, the remarkable thing isn’t that you behave like this. All sorts of people behave like this all the time. The remarkable thing is that the genuine sciences have mostly been able to do away with this sort of thing.

The signal fact is that macroeconomics — for all of its math and data — has not.

As I think everyone is noticing.

The math and the data haven’t allowed macroeconomics to escape from the non-scientific world where BS has a place, and is almost welcome. It’s not welcome in other parts of science — but we can read macroeconomists trading in it every day, and launching another pile at one other everyday.

And Hayek’s scientific work is a repeated victim.

Perhaps Keynes set the tone for the whole profession (see Pigou’s review of Keynes’ _General Theory_).

17. July 2011 at 18:15

Scott, you falsely suggest that the Hayekian causal mechanism is a mono-causal explanation.

But, that is not what the theory says, and that is not what any Hayekian says.

Scott, you falsely suggest that the Hayekian mechanism involves nothing more than and only the over-building of houses in isolation from every other production and consumption and financial process in the economy.

But, that is not what the theory says, and that is not what any Hayekian says.

Scott, if it has been explained to you what you write about the theory doesn’t display the slimmest understanding of the theory — why assume that you have any idea what relation patterns in the data might have to the causal mechanism?

17. July 2011 at 18:22

Here’s a simple Turing Test of your understanding of Hayek’s macro, Scott:

In what way would data showing a slump in commercial construction be compatible or incompatible with the Hayekian causal mechanism?

Similarly, in what way would data showing a slump in commercial construction employment be compatible or incompatible with the Hayekian causal mechanism?

You’ve staked a claim as a reputable non BSing scientist that this data counts _against_ Hayek’s causal mechanism.

Explain it.

17. July 2011 at 19:20

Scott, since I’ve been posted and responded to here – for each of which I am grateful, by the way – here are replies to your comments above.

You write: “Wealth doesn’t flow into markets. Markets are where transactions occur-each purchase is a sale.”

A more precise definition of “market” than I used may require the net flow of wealth to be zero by definition. But this doesn’t address my point that changes in the raw number of houses being built doesn’t necessarily tell us what we want to know, which is how much wealth went into building those houses and how that compares to their real value.

You write: “In this blog I’ve been highly critical of many of the things he mentions, including the big minimum wage jump and Dodd-Frank. But those didn’t cause NGDP to collapse.”

I haven’t been a regular reader of your blog before now, and certainly didn’t mean to imply that you supported the policies I mentioned. From this brief exposure, it looks like there is a lot of interesting material being posted here.

I also didn’t intend to say that the minimum wage jump or Dodd-Frank caused the NGDP collapse your model describes. I do claim that raising the minimum wage looks like a factor contributing to the observed high unemployment numbers for low-wage workers, and that Dodd-Frank is part of a series of bad policies which are likely to reduce economic growth.

You write: “BTW, the Fed does QE2, not the Treasury.”

I stand corrected on that point.

None of the above addresses my basic argument: The measurable quantities going into these mathematical models probably don’t come anywhere close to describing the real factors driving our economic performance. Certain of them, such as the Fed actions, may be amenable to that sort of modeling. But others do not seem to be, except perhaps in a very ad-hoc way. That category would include the impact of insecurity of property rights and the uncertainty about taxes on the willingness of entrepreneurs to invest, and of large, far-reaching, poorly-understood laws whose details are getting worked out long after the laws themselves are passed. In the absence of good descriptions of those factors, is it reasonable to expect models to make reliable predictions?

17. July 2011 at 19:39

Scott, I re-submit my explanatory challenge.

On your account, unemployment numbers are explained by the fall in NGDP.

Your NGDP account therefor has good to explain the vast differences in the distribution of unemployment and the incidence of unemployment. It also has to explain the pattern of geographic distribution of unemployment, and the unfolding of unemployment by sector across time.

Explain how your “NGDP did it” explanation accounts for the dramatic patterns within the unemployment numbers, e.g. the massively higher percentages of unemployment in construction as compared with other sectors, or the geographical distribution of extremely high unemployment in such places as California and Nevada.

Etc.

There are all sorts of dramatic patterns in the data that demand explanation.

If your explanation is plausible, it requires the capacity to discharge this gaping demand for explanation.

17. July 2011 at 20:31

Scott,

Thank you for the information on the IMF as a source.

Andujar

18. July 2011 at 03:54

I think this quoted from Chris Koresko above hits on something for me:

“Never mind the rate of housing starts per unit population; what matters for this argument is the amount of wealth flowing into the housing market, and the degree to which that wealth was well-invested.”

Scott may argue over the semantics of “wealth flowing”, but I would like to see a good explanation of what is captured in the following graph beside the rest of Scott’s argument

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/_pMscxxELHEg/SwwLLoLo-TI/AAAAAAAAG4E/lkFRcPAVoZw/s1600/Q3PriceIncome.jpg

18. July 2011 at 04:13

[…] Jim Glass sent me some very interesting data on household formation, which casts a very different light on the recent housing crash. By my simple measure recent housing starts peaked with an inventory of 40% of an average year’s worth of starts above the trend line in 2007. That’s a cyclical high but a typical one. About the same or a little higher was reached in three other cycles since 1960. […]

18. July 2011 at 08:32

inthewoods, You said;

“It was in 2006 if you were listening to the right people. I, for instance, had been talking about a collapse in housing prices starting in 2005.”

You are wasting your time with those sorts of statements over here. I put zero weight on the ability of pundits to predict markets. It’s all luck. My 7 year old daughter thought markets were too high in 2006. So what? The housing bubble predictors were wrong in most countries in the early 2000s. They lucked out and happened to be right in America.

Consumer spending is a component of GDP, as are investment, G, and NX. That’s a completely separate question from what causes NGDP to change. Monetary policy drives NGDP, as the Zimbabwe case shows. Unless you think consumer spending could make NGDP in Zimbabwe go up a trillion percent.

Greg, You said;

“The geometrically larger percentage size of construction unemployment is an explanadum pattern that demands explanation.”

That’s a completely different argument. Sure it demands an explanation, but you were arguing it affected GDP significantly. We could explain why beekeeping jobs collapsed, but it wouldn’t explain GDP.

You asked:

“In what way would data showing a slump in commercial construction be compatible or incompatible with the Hayekian causal mechanism?”

Hakek would say that the reason commercial construction did not collapse in 2006 is because it wasn’t overbuilt. Hayek would say that the secondary deflation of 2008-09 caused commercial construction to tank in late 2008. And I completely agree with Hayek. Did I pass the Turing test?

Chris, You said;

“But this doesn’t address my point that changes in the raw number of houses being built doesn’t necessarily tell us what we want to know, which is how much wealth went into building those houses and how that compares to their real value.”

Ok, are you saying the problem with housing starts is that it doesn’t account for changes in the average size of homes? I.e. we might have been building bigger houses, so the wasted capital in the housing sector is bigger than the simple numbers show. I could accept that–I don’t know how empirically important it is.

You said;

“I also didn’t intend to say that the minimum wage jump or Dodd-Frank caused the NGDP collapse your model describes. I do claim that raising the minimum wage looks like a factor contributing to the observed high unemployment numbers for low-wage workers, and that Dodd-Frank is part of a series of bad policies which are likely to reduce economic growth.”

I happen to agree, although I think they area modest part of the total story. I still think monetary policy is the biggest villain.

Regarding your final point, in other posts I’ve discussed how economies sometimes began growing fast after really bad statist policies were instituted (US after 1933, Argentina after 2002) in both cases a huge reversal in AD (from highly contractionary to highly expansionary) did the trick. Obama’s problem is that he doesn’t have the big AD boost, and the conservatives’ problem is that the fall in AD actually led to many of the statist policies they oppose. Indeed it’s one reason he was elected. And yet many conservatives are opposed to more AD.

Greg, You said;

“Your NGDP account therefor has good to explain the vast differences in the distribution of unemployment and the incidence of unemployment.”

During recessions unemployment rises more in cyclical industries, such as construction and durable manufacturing.

Barnley, I don’t have much new to say about the price runup, I accept almost all explanations:

1. Restrictive zoning, because these are mostly land prices, not housing prices. Prices didn’t soar in Texas, despite high demand.

2. More demand for housing because of rapid immigration, bad housing policies (the GSEs, tax deductions, etc), bad regulations that cause banks to take excessive risks (FDIC, TBTF), financial innovation, etc, etc.

18. July 2011 at 08:36

No I wasn’t. You were. In any case, matters of degree quickly get swallowed by weasel words like “significantly” in these sorts of debates.

“Sure it demands an explanation, but you were arguing it affected GDP significantly.”

18. July 2011 at 08:37

Scott, that is an empirical description, it is NOT a causal explanation of the pattern.

Scott writes,

“During recessions unemployment rises more in cyclical industries, such as construction and durable manufacturing.”

18. July 2011 at 11:35

Scott, I want to push back a little on your reply to Kindred’s comment above.

You acknowledge that the financial crisis actually started in mid-2007 but you say that “even in mid-2008 it wasn’t severe enough to lead to expectations of recession.”

The severity of the post-Lehman phase of the financial crisis tends to obscure the seriousness of what happened in the thirteen months leading up to Lehman. Remember what we saw starting in August 2007 and persisting through the subsequent year:

— a massive contraction in the ABCP market, coupled with very big spikes in interbank, Eurodollar, and other money market spreads

— significant increases in credit spreads, both consumer and corporate, in every major category I believe

— a huge contraction in issuance volumes in just about every ABS category by the end of 2007 (even apart from non-agency RMBS, which of course totally halted)

— effective halt in CMBS issuance volumes by the end of 2007

— the run on Bear Stearns in March 2008, followed by a big precautionary shift by dealer firms toward cash equivalents, reducing their exposures to the capital markets.

I’m sure I’m leaving out a bunch of things. But this was a very serious liquidity and credit event. By what standard was it “not severe enough” to “lead to expectations of recession” in mid-2008? How severe would it have had to have been?

You seem to anticipate this line of argument because you present a fallback argument (“even if this view is wrong …”) in your post. You say “there is not a shred of theoretical or empirical evidence linking the current 9.2% unemployment with the 2008 financial crisis.”

But what would such empirical evidence look like — even a “shred” of it? As a historical matter there is an empirical regularity which seems quite relevant. Quoting Reinhart and Rogoff: “the aftermath of banking crises is associated with profound declines in output and employment. The unemployment rate rises an average of 7 percentage points during the down phase of the cycle, which lasts on average more than four years.”

Can’t we legitimately postulate that there might be some cause-effect relationship between financial crises and unemployment crises? And why shouldn’t we suspect that that cause-effect relationship might apply to our current situation?

We saw a financial crisis that started in 2007Q3, climaxed in 2008Q4, and finally subsided (more or less) in 2009Q2. We saw an economic crisis that started in mid-2008 and is ongoing. I don’t purport to have proof of causation – we can only draw inferences here – but the idea that there might be a causal relationship here doesn’t seem that farfetched.

18. July 2011 at 11:41

You’re still getting the causal direction wrong …

“Sure it demands an explanation, but you were arguing it affected GDP significantly.”

The collapse of construction & construction employment is a product of the price distortion caused unsustainable production structure distortion.

There are several co-determinants of the systematic and economy wide price distortion across time and across all production processes and consumption plans.