Negative IOR need not hurt bank profits, if done correctly

The ECB moved more aggressively than expected to cut IOR and increase QE. Today I will explore the effects, beginning with the banks. Recall how negative IOR was supposed to be so bad for bank profits. It seems those theories were wrong:

Banks have warned that negative interest rates are eroding their profitability. The rates cut into banks’ net interest margins as lenders have been reluctant to pass on the cost of negative rates to all but the biggest retail customers.

To offset some of the pain to banks, the ECB will provide cheap loans through targeted longer-term refinancing operations, each with a maturity of four years, starting in June 2016. These loans could potentially be provided at rates as low as minus 0.4 per cent, in effect paying banks to borrow money. Banks will also benefit from a refinancing rate of 0 per cent.

Shares in eurozone banks rallied sharply after the ECB announcement with Deutsche Bank up 6.5 per cent, Commerzbank up 4.9 per cent, Société Générale up 5.4 per cent and UniCredit up 8.2 per cent.

Over the years I’ve pointed out that there are things that central banks could do to offset the hit to bank profits. For instance, they could raise IOR on infra-marginal reserve holdings, while they lowered IOR at the margin. I did not propose the exact offset discussed above, but it seems that the general concept is workable. Negative IOR need not be a problem for banks, if done correctly.

European stocks rose sharply on the more aggressive than expected announcement and the euro fell in the forex markets. Oddly, however, for the 347th consecutive time the “beggar-thy-neighbor” theory was falsified by the market reaction. Not only did Europe’s actions not hurt the US, our stocks soared higher on the news:

Dow futures added more than 150 points after the ECB cut the deposit rate to negative 0.4 percent from minus 0.3 percent, charging banks more to keep their money with the central bank. The refinancing rate was also cut, down 5 basis points to 0.00 percent.

I warned people to be careful after the Japan announcement; the EMH is not a theory to be trifled with. As you recall, Japanese stocks soared and the yen fall sharply when negative IOR was announced in Japan. But then a few days later both markets went into reverse (probably for unrelated reasons). Many people assumed it was a delayed reaction to the negative IOR. That’s possible, but markets generally respond immediately to news. With the European moves today we see yet another confirmation of market monetarism:

1. Policy is not ineffective at the zero bound. So do more!!

2. Reducing the demand for the medium of account (negative IOR) is expansionary.

3. Increasing in the supply of the medium of account (QE) is expansionary. I.e. the supply and demand theory is true.

4. There is no beggar-thy-neighbor effect from monetary stimulus.

Market monetarists were the first to propose negative IOR. It’s our idea. When your ideas are correct, they help to explain how the world evolves over time. Things make sense. In contrast, people with a more “finance view” of monetary policy have been consistently caught flat-footed. Note that these people are represented on both the right and the left, and they have been consistently wrong in their views of monetary policy at the zero bound.

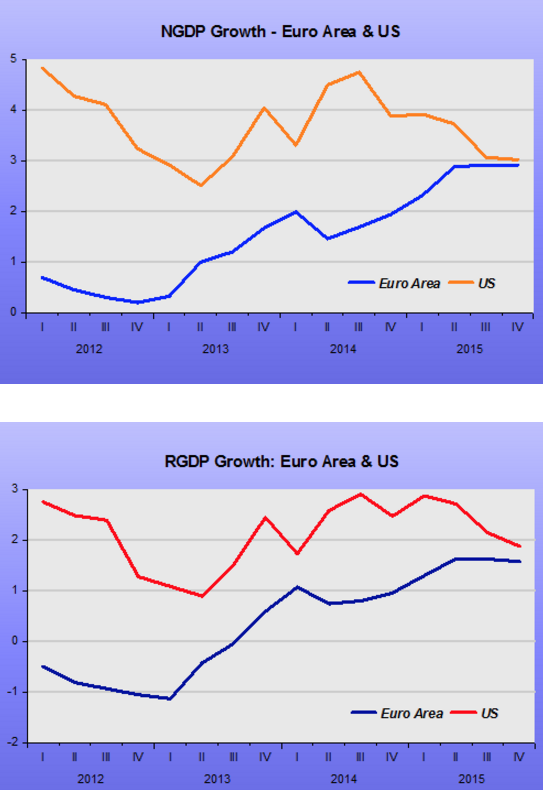

BTW, James Alexander has a post showing that eurozone growth has nearly caught up with the US:

Notice that at the beginning of 2012, NGDP growth in Europe had been running at less than 1% over the previous 12 months. That’s the horrific situation that Draghi inherited from Trichet. Draghi did move much too slowly at first, but at least things are beginning to look a bit better for the eurozone. Still, Draghi needs to do more, as the eurozone is likely to fall short of its 1.9% inflation target.

Even better, the ECB needs to change its target, and set a new one high enough so that the markets are not expecting near-zero interest rates for the rest of the 21st century:

Take overnight interest rate swaps. They imply European Central Bank policy rates won’t get back above 0.5 percent for around 13 years and aren’t even expected to be much above 1 percent for at least 60 years.

Update: The euro later reversed its fall. But note that US stocks soared even after the initial plunge in the euro. It’s interesting to think about why the euro reversed its losses–perhaps a view that the ECB action will make the Fed less likely to raise rates? Or because it was expected that the action would lead to stronger eurozone growth? What do you think?

Update#2: Commenters HL and GF pointed out that the euro rose in value after Draghi indicated (in a press conference) that the ECB would probably not push rates any lower.