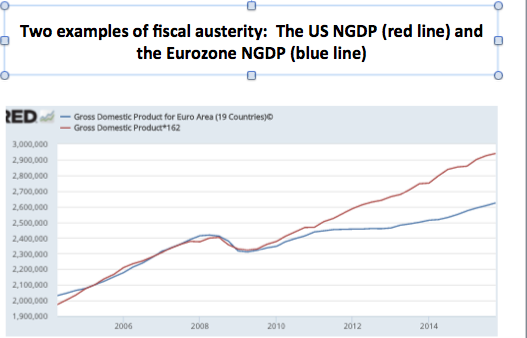

In this year of Trump, it has become fashionable to sneer at things you don’t understand. Like the EMH. TravisV sent me an example from the normally sensible Joe Weisenthal and Matthew Klein. It’s also a good example of why I don’t use Twitter. Lots of snarky comments that make a person look smart, but on closer examination merely show that the writer is witty.

JP Koning pointed out that I viewed yesterday’s market reaction as supporting the claim that the ECB actions helped European banks. Stocks rose on the announcement, and bank stocks rose especially sharply. I stand by that claim. Then Joe Weisenthal responded:

Almost all of the gains to which Sumner is referring to in this post were erased by the end of trading.

That’s true, but completely irrelevant. The problem here is that people don’t understand markets. Equity prices are always moving around. When you do an event study, what matters is the market response immediately after the announcement, not later in the day. You may “feel bad” that the stock rally didn’t last, but markets aren’t about feelings, they are about cold hard facts. In fact, if markets never reversed gains made early in the trading day, then the EMH would be entirely false. A few weeks back I was sent an email by a guy showing that previous BOJ surprises were followed by additional gains in the days and weeks ahead. Free money? Nope, right after making that observation, the Japanese markets reversed, and lost more than the initial gain from the BOJ’s recent decision to go negative. It’s just one coin flip after another.

Matthew Klein responds:

LOL

Joe Weisenthal responds:

Sumner’s insistence on using snap market reactions to judge policy a success or failure is head-scratching.

I’m honored that Joe thinks I invented “event studies”—that this is all my peculiar idea, but there are actually thousands of academic event studies. I’ve seen Paul Krugman favorably discuss the outcome of event studies. Then this was added to the Twitter thread, by someone else:

Sumner’s view is unfalsifiable. He will now say that ECB did not do enough.

Actually, event studies are among the most “falsifiable” of all academic studies. But notice how misleading this is. I actually did say the ECB needs to do more, but the commenter is giving readers the impression that I use that as an excuse for the decline in stocks later in the day. That is completely false, as it would not be consistent with the EMH. Yes, they need to do more, but my explanation for the decline in stocks later in the day was exactly the same explanation as the financial press provided. That’s right, publications like the Financial Times are apparently just as clueless as I am. I wonder why Weisenthal doesn’t say, “The mainstream financial press’s claim that asset prices reversed later in the day on Draghi’s comment that no further rate cuts were likely was head-scratching”? Perhaps he doesn’t know that this is what happened.

Asset markets are ruthlessly efficient. If they were not it would be easy to get rich. Just sell European bank stocks short after the “irrational” stock price run-up following an ECB announcement. Indeed I’d guess that even EMH skeptics like Robert Shiller mostly buy into the idea that markets respond immediately to new information. What reporters don’t understand is that the real world is messy. Asset prices change all the time. The standard deviation of daily changes in stock price indices is about 0.8%, which it pretty big (or at least it was last time I looked–for the 20th century). But the average change in any 10-minute interval is far smaller, so when you have a dramatic policy announcement, it’s often possible to see the market response–it really jumps out when you look at the data. And when you have many such announcements and the markets almost always respond as monetary theory would predict, then you can be especially confident.

Here is what apparently happened over the last couple of days:

1. Stocks rallied and the euro fell on the more stimulative than expected ECB announcement. Totally consistent with what we know about monetary policy.

2. Stocks fell sharply and the euro rallied on Draghi’s (perhaps misunderstood) statement at a press conference. Again, totally consistent with what we know about monetary policy

3. I don’t know why the markets reversed course again today, but James Alexander watches these things more closely than I do, and here’s what he reports:

There seems to have been a lot of public and private follow upon Friday from the ECB to reinforce their original, positively-taken, message.

“The European Central Bank embarked on a rearguard action to win over skeptical investors on Friday, a day after chief Mario Draghi unveiled a new stimulus package but blunted its impact by suggesting the ECB would not cut interest rates again.

A number of top ECB officials, both publicly and behind the scenes, spoke out in support of the measures Draghi announced on Thursday although some recognized the ECB had muddled its message to financial markets.”

http://reut.rs/1U6EeID

I have absolutely no idea whether that Reuters story is right or wrong, but it’s the sort of information that moves markets all the time. And markets should react to that sort of information, if it sends signals about future policy intentions. I’m sorry it’s so complicated, but that’s the world we live in.

Unfortunately, not all policy experiments are perfectly clean. In the old days you could look at fed funds futures prices, and then see if the Fed cut rates more or less than expected. The event studies were highly reliable. I admit that announcements are now somewhat more complex, but let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater; they are still far better than any other method. What’s the alternative, wait 6 months and see what happens to the macroeconomy? Really? Like we know what the macroeconomy would have looked like if the decision had been a few basis points loser or tighter? That’s ridiculous.

This skepticism about market efficiency was one cause of the Great Recession (Joe’s probably thinking “Good Lord, Sumner’s now blaming me for the Great Recession, he really needs to take his meds.”) The Fed scoffed at market predictions of sharply lower inflation, right after Lehman failed. The markets were right and the Fed blew it.

Markets may look crazy, but only in the sense that an extraterrestrial being that was 100 times as smart as you or I would seem crazy. Asset prices move around all the time because the future is highly uncertain, and seemingly innocuous comments (like Draghi’s suggestion that no more rate cuts are expected) are actually very consequential.

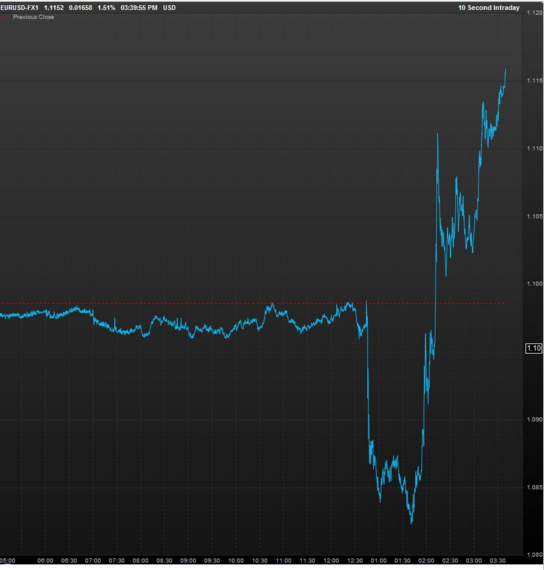

If the ECB skeptics are correct, and market movements are just so much noise, then I must be hallucinating to claim I can connect any given market movement to a specific policy announcement. OK, then take a look at the graph below, showing the value of the euro against the dollar, which is from Timothy Lee’s excellent Vox story on the day’s events. Suppose you didn’t know what time of day the ECB made it’s initial announcement and also the time when Draghi said this was going to be the final rate cut. Do you think you could guess, just from the graph? Maybe I’m hallucinating, but I think I see a meaningful fall in the euro at about 12:45, and a big jump just before 2PM. Gee, I wonder what those correspond to? It turns out the original ECB announcement was at 12:45. And Draghi’s statement that it was the final rate cut was at 1:56:30—just before 2pm. Huge market moves right after important new information. What an astounding coincidence!! After all, event studies are useless, right? Asset prices are just random noise.

PS. People are always telling me to get on Twitter. This is a perfect example of why I prefer blogging. You can have the sort of serious discussion in blogs that’s just not possible in 140 characters.