One argument against market efficiency is that asset prices are subject to speculative bubbles, where prices rise (or perhaps fall) more than can just justified by fundamentals. Today I’ll discuss why this theory is so hard to evaluate.

During my lifetime, I’ve seen three major asset price movements that looked, in retrospect, rather irrational:

1. The 1987 stock market boom and crash.

2. The late 1990s NASDAQ boom and crash

3. The housing “bubble” of 2006.

During the first 8 months of 1987, the Dow soared by about 40%, and then fell by a roughly equal amount late in the year, with a notable 22% decline on a single day (a record, by far).

After the crash, the pre-crash prices were widely viewed as a bubble, and not justified by fundamentals. Today those prices seem quite reasonable, and if anything it’s the post-crash levels that seem too low. On the other hand, the size of the price change, particularly the 22% decline in a single day, is hard to square with fundamental theories of asset prices, where stocks move only on new information. Nothing occurred on October 19, 1987, that would justify such a large price move. So in one of two respects, 1987 still looks bad for the efficient markets theory.

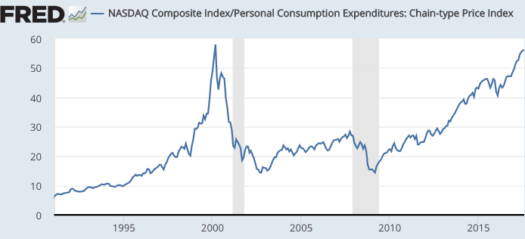

2. In the late 1990s, the tech-dominated NASDAQ soared from below 1000 to a peak of 5048 in March 2000. Then it fell 1114 in October 2002. During the 21st century, the March 2000 levels have been almost universally viewed as an insane bubble, whereas the October 2002 levels have received little comment. And yet a good case can be made that it is the October 2002 levels that are far out of line with fundamentals, at least based on today’s NASDAQ (over 5800 as I write this post.)

In fairness, the (PCE) price level is up 35% since March 2000, so the real NASDAQ is still considerably lower than at the 2000 peak. Still, even in real terms the NASDAQ is higher than it was just a couple months before or after the March 2000 peak. It should also be noted that the dividend yield on NASDAQ was lower than the real interest rate back then, so investors considerably over-estimated the returns they could expect from buying tech stocks at those lofty levels. I’m not claiming that the March 2000 prices look correct, in retrospect. But then if you go back in time and cherry pick the day when valuations were at their absolute peak, then of course it’s not going to look like the optimal time to buy that asset.

I’d also point to the 1114 low in October 2002, which looks, in retrospect, even more “wrong”. Obviously if I wrote this post in 2002, I would have reached very different conclusions about the 2000 “bubble”. The point here is that in retrospect, previous asset prices will almost always look “wrong”. And since we never reach the end of time, we don’t ever get a definitive reading on what asset price level would have been correct, at any given point in time.

3. As far as the 2006 housing bubble, two subsequent events have cast doubt on whether the prices actually were irrationally high in 2006. First, housing prices in many other countries with similar price run-ups, such as Canada, Australia, Britain and New Zealand, did not crash, and indeed are as high as in 2006, or even higher, even in real terms. (Ireland did crash like the US, to round out the English speaking countries.) Second, home prices in many coastal cities like New York, Boston and coastal California have soared back up to “bubble levels”, and even higher. Many central US regions like Texas never saw a price bubble. Yes, some cities never did recover, but Kevin Erdmann has many posts that provide further evidence that the so-called bubble was not as irrational as it now seems, given what people knew at the time.

This post is also very provisional. In two years, asset prices might be much higher than today and the idea of a 2000 NASDAQ bubble and a 2006 housing bubble may be almost completely discredited. (Just as the 1987 stock bubble was later discredited.) Or asset prices may fall sharply and this post may seem mistaken. That’s why I always try to take a pragmatic approach to bubble theory. What’s in it for me? How do bubble theories help me to live my life more effectively as an investor, as an academic, and as a voter? So far I don’t see much use for bubble theories, but I’ll keep an open mind.

Off topic: I watched part of Trump’s press conference this afternoon, which reminded me the the “strawberries” scene in The Caine Mutiny. I’ve got news for Trump—this is your honeymoon period. It will get far worse. If Trump’s already showing signs of being mentally unstable after a few minor flare-ups, what’s it going to be like when his administration gets into serious trouble? Anyone who watched the press conference and still doesn’t understand why I think Trump is a spoiled, immature brat, then, well then I have nothing to say to you.

(Not that I could care less, but the rest of the world is laughing at us. We elected a right-wing version of Chavez, or if you prefer a Duterte or a Berlusconi. I feel bad for the reporters who had to sit through that clown show. And thank God that there are a few GOP senators who are willing to tell the truth.)

PS. I also recommend this FT article on bubbles:

The background history to these booms confirmed what historians of bubbles had already shown: that they always have at least some backing from the fundamentals. Bubbles may end up being irrationally expensive, but they are not stupid. They arrive when an exciting new development — canals, railways, the internet — creates confusion over the future value they will create. As he puts it, “there was at least some method to the madness of investors”.

He found 72 cases of a market doubling in a year. In the following year, six doubled again, and three halved, giving back all their gains: Argentina in 1977, Austria in 1924 and Poland in 1994.

For doubling in three years, he found 460 examples. In the following five years, 10.4 per cent of them halved. The possibility of halving in any three-year period, regardless of what had come before, was lower than this but not dramatically so: 6 per cent.

On this basis, arguments made by many (including me) that central banks should concentrate more on pricking bubbles before they get too big begin to look threadbare.