Bernanke believes Fed policy since mid-2008 has been the tightest since the 1930s

I thought my previous post was a big deal, but with a few exceptions other people didn’t seem to think so. So I’ll keep hammering the point home until others take notice, or tell me why I’m wrong.

This might be a good time to take stock of the amazing recent success of market monetarism. I can see at least four key ideas that have gone from fringe to mainstream since we started this crusade in late 2008:

1. Pointing out that the Fed could and should do much more to address the recession.

Here’s a quotation from Ryan Avent last year:

I SEE that Scott Sumner is taking a victory lap of sorts””not unearned””over the fact that views of monetary policy have come full circle since the years before the crisis. Once upon a time, the Fed was viewed as having near-absolute power over the path of the economy. Then crisis struck and many argued that the Fed had run out of ammunition and fiscal policy was required. Eventually people began arguing that the Fed could do more and should do more, thanks largely to the efforts of Mr Sumner himself. Now you have people like, well, yours truly saying that the Fed had a path to recovery in mind, such that a tightening of economic slack faster than it preferred would trigger a policy response. Once more, the economy is entirely in the Fed’s hands.

Of course lots of other market monetarists played a big role in this sea change in pundit opinion.

2. The growing popularity of NGDP targeting

The idea was endorsed by Goldman Sachs, Paul Krugman, and Christina Romer. All three mentioned market monetarists like Beckworth and me in their endorsements.

3. The growing recognition that people had reversed causality–to a significant extent the recession caused the debt crisis, or at least greatly worsened it in late 2008.

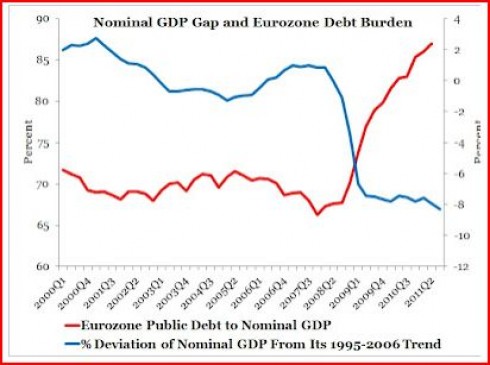

David Beckworth has an excellent post that shows the relationship between falling NGDP and the eurozone debt crisis:

David then quotes Paul Krugman on the euro crisis:

If the peripheral nations still had their own currencies, they could and would use devaluation to quickly restore competitiveness. But they don’t, which means that they are in for a long period of mass unemployment and slow, grinding deflation. Their debt crises are mainly a byproduct of this sad prospect, because depressed economies lead to budget deficits and deflation magnifies the burden of debt.

Translation: “Depressed economies” means low RGDP. Low RGDP plus deflation means low NGDP. I.e., low NGDP worsens debt problems. It’s increasing clear that the second and more severe phase of the US financial crisis in September 2008 was triggered by the dramatic fall in NGDP between June and December 2008, the sharpest since the 1930s. Let me know if Krugman applies his reasoning to the US situation; that would be a big win. (Of course a cynic would claim he’s more interested in looking for excuses when the crisis seems caused by reckless government borrowing, than when it seems caused by reckless private sector borrowing. But I’m not a cynic.)

4. The stance of monetary policy is indicated by NGDP growth, and thus policy since mid-2008 has been ultra-contractionary.

This is clearly the view that was most at odds with conventional wisdom. Almost everyone simply assumed money had been “extraordinarily accommodative,” even though exact opposite was true, using the metrics for easy and tight money in mainstream textbooks like Mishkin. But now we have the most conventional of conventional wisdom endorsing market monetarism. Here’s Ben Bernanke himself:

Ultimately, it appears, one can check to see if an economy has a stable monetary background only by looking at macroeconomic indicators such as nominal GDP growth and inflation.

Inflation since July 2008 has been the lowest since the mid-1950s, and way below the Fed’s target. NGDP growth has been the lowest since Herbert Hoover was president. If you average those two metrics, it’s the lowest since the 1930s. Since Bernanke believes these are the proper metrics for judging the stance of monetary policy, he obviously believes the Fed has run an ultra-contractionary monetary policy since July 2008, right before the severe phase of the debt crisis.

I’d say that market monetarism is on a roll. It’s now conventional wisdom that the Fed could have and should have done more. Not conventional wisdom among average people, but among the best and brightest in the blogosphere. And even Ben Bernanke believes that Fed policy has been ultra-contractionary if measured using appropriate metrics. There is growing awareness that this tight money reduced NGDP growth sharply, dramatically worsening the debt crisis in both America and Europe. And elite opinion-makers on both the left and the right are increasingly likely to see NGDP targeting as the answer.

Those who have only recently started following blogs might wonder what’s the big deal. But go back to late 2008 and see what people believed before market monetarism got going. We’ve significantly transformed elite pundit opinion on four major issues. That’s worth celebrating.

PS. This list is by no means exhaustive. Nick Rowe influenced how people think about Fed signaling. David Glasner showed that the excessively tight money changed the stock market reaction to inflation–essentially showing that stock investors are market monetarists too. Marcus Nunes was the first to show how Bernanke was rejecting the very advice he’d given the BOJ in similar circumstances—an idea that recently got widespread coverage due to a Lawrence Ball paper. And I could go on and on.

Tags:

1. March 2012 at 07:34

Scott,

OK, let’s talk about empirics here (as commenter ‘dwb’ asserted to me previously) since I understand you have no theoretical foundation behind your imaginary project.

You mentioned that an economic expansion engine in your project is working through the “hot potato” effect.

Please provide some empirics where the “hot potato” effect (a.k.a. monetary printing press) has caused an economic expansion.

I don’t know such circumstances in history. I know events when inflation was able to heal the wounds caused by the deep economic crisis but I don’t know where it could have started being the engine of economic growth.

Regards

P.S. Please don’t throw your customary dogmatic statements as the answers. And if you can’t provided a serious answer to this question, then just close your dreadful project and stop confusing desperate people looking for a simple answer to the complex economic problem. You are smart and decent guy for doing that.

1. March 2012 at 07:38

kudos.

not sure i agree with the following:

Not conventional wisdom among average people, but among the best and brightest in the blogosphere.

I see a lot of Fed-bashing in the political rhetoric these days (wheras it used to be Greenspan was idolized).

I think many people intuitively understand that they (the economy) are sick, it takes a Dr. to figure out why.

1. March 2012 at 08:03

if you can stand it, more ACK!!! Bernake on Bernanke:

p4:

But I also believe that there is compelling evidence that the

Japanese economy is also suffering today from an aggregate demand

deficiency. If monetary policy could deliver increased nominal

spending, some of the difficult structural problems that Japan faces would no longer seem so difficult.

p7:

Alternative indicators of the growth of nominal aggregate demand

are given by the growth rates of nominal GDP (Table 1, column 4) and of nominal monthly earnings (Table 1, column 5). Again the picture is consistent with an economy in which nominal aggregate demand is growing too slowly for the patient’s health. It is remarkable, for example, that nominal GDP grew by less than 1% per annum in 1993, 1994, and 1995, and actually declined by more than two percentage points in 1998.

p10 (too long to insert): “The argument that current monetary policy in Japan is in fact quite accommodative rests largely on the observation that interest rates are at a very low level.”

…

p12 “This example illustrates why one might want to consider

indicators other than the current real interest rate””-for example, the cumulative gap between the actual and the expected price level””-in assessing the effects of monetary policy.”

i could go on and on but its way too depressing because a lot of this paper could have been taken right from, ahem, a monetarist blog.

1. March 2012 at 08:03

oops. link: http://www.princeton.edu/~pkrugman/bernanke_paralysis.pdf

1. March 2012 at 08:29

I’ve changed my mind, even with inflation, low NGDP doesn’t tell you anything at all. It is perfectly consistent with low V rather than low M, unless you can prove low NGDP = low M you have nothing.

1. March 2012 at 08:47

“But go back to late 2008 and see what people believed before market monetarism got going.”

I have a brokerage report titled “INFLATION IS CONSENSUS”

The broker? Merrill Lynch

The date? JANUARY 2009

1. March 2012 at 09:05

My prior post is important, because I’m starting to hear the gremlins on Wall St grumbling about how the Fed needs to bring in it’s tightening timeline.

Why? To beat back the inflationary impulse of Iranian oil sanctions.

The gremlins don’t read academic research, but they do read Amity Shlaes economic horrorville.

1. March 2012 at 09:17

‘Please provide some empirics where the “hot potato” effect (a.k.a. monetary printing press) has caused an economic expansion.

‘I don’t know such circumstances in history.’

Maybe you should start with Friedman and Schwartz.

1. March 2012 at 09:36

At this point, Market Monetarism has prevailed in the Internet, and is crowding out other positions elsewhere–except perhaps where it really counts, in the FOMC.

We MM’ers still have a lot of work to do to sweep the tight-money currency cultists and gold-voodoo nuts off the right-wing stage, where they are stoutly entrenched, engaged (in their minds) in a mythic and epic battle against inflationary theft and currency debasement. The Theo-Monetarists and Econo-Shamans, often with hidden partisan agendas, have their long knives unsheathed. They want this economy dead—until the GOP regains power.

And still have the Krugmanites hogging the left-wing stage braying for bigger federal deficits.

Tough fight ahead—but compare to a just few years back. Then I wrote to Marcus Nunes of lighting a single candle to fight the darkness (Eleanor Roosevelt-style). Now, it may be a monetary dawn.

Too late to help many who have become permanently unemployed, or watched their real estate equity shrivel into a negative, or had their businesses collapse, or could not ask that mate for a hand in marriage, gave up college, etc.

These are the stories largely untold. Yes, it is better now than the Great Depression, but many dreams have been wrecked. And not dreams of being rich and famous, but dreams of middle-class security and contentment.

Sheesh, cannot we devise an economy that delivers results to people who work hard?

No, welfare and statism is not the answer.

Market Monetarism is the answer.

Forward!

1. March 2012 at 09:58

Patrick R. Sullivan,

Maybe you should stop throwing empty phrases here.

And think first why inflation didn’t work in Germany, Zimbabwe, Russia, etc.

Then you would think that something is wrong with the “hot potato” theory. Perhaps it is just myth, some kind of urban legend. Then you may think if you smart enough that economic damage brought by inflation overcomes its supposed benefit and commonly inflation (especially taken at large quantities) has a detrimental impact on the economy and inflation by itself can’t be an economic cure.

And I don’t care very much what Friedman and Schwartz said about the topic. Their advice was relevant to their times (as well as Karl Marx’ or Keynes’ advices were relevant to theirs). Distinct from you, I (and Scott Sumner too) can think about the economic matter independently.

1. March 2012 at 10:19

Unfortunately, there is a difference between saying “2003 Ben Bernanke believes that monetary policy has been contractionary” and 2012 Bernanke believing that to be true. On another note, there seems to be a big push developing in Japan for a higher inflation target (which is a 3rd or 4th best policy target, but still better than the current situation).

1. March 2012 at 10:37

Ravi-

Yeah, BoJ will allow one percent inflation, Big whoop. Also, beware–when an economy generates huge bond-holding class. Curtains for economic growth.

1. March 2012 at 10:57

The problem is all inside your head, she said to me,

You can’t pay back 200 percent of GDP,

You have to negotiate, if you want your country free,

There must be 50 ways to leave your lender.

You really don’t want the IMF to intrude,

Furthermore, they’ll force austerity for the interest that’s accrued,

Imagine your middle class, subsisting on cat food,

There must be 50 ways to leave your lender.

Fifty ways to leave your lender.

You just stretch out the loan, Joan,

Cut the creditors’ hair, Claire,

Or boost GDP, Lee,

Just listen to me.

Print more money, honey.

No need to pay back, Jack!

Structure a default, Walt.

And get yourself free.

http://www.npr.org/blogs/money/2012/03/01/147720368/50-ways-to-leave-your-lender

1. March 2012 at 11:03

Scott,

I even have an explanation why “hot potato” theory is a hoax.

It looks only at one side of equations — consumers. Yes, consumers are trying to get rid of money as soon as possible.

But we should take into account the other side — businesses. High inflation makes all normal businesses unprofitable. Due to the lengthy production process, it becomes unprofitable to do any business activities except the speculative trades.

As a result, the real economy suffers that we have observed in practice in the countries with high inflation.

1. March 2012 at 11:49

What the heck is the blue graph supposed to mean? It is “% Deviation of Nominal GDP from its 1995-2006 Trend.”

Deviation : ok, it’s a measure of how much nominal GDP is unlike the trend. If deviation is 0 %, then nominal GDP is the same as its trend, right?

This doesn’t make sense to me.

1. March 2012 at 11:58

“And think first why inflation didn’t work in Germany, Zimbabwe, Russia, etc.”

Empty phrase.

1. March 2012 at 12:17

Scott,

I have a hard time creating a hypothetical falsifiable experiment for your NGDP writings–(of course, that is one of the most difficult things to do in Economics). But what I am getting at is the concept of “if X (i.e., the Fed) implements explicit policies A, B, and C it will increase/(decrease) NGDP over period of time Y”. That is, what is the NGDP model?

From your readings, I “hear” the following—“NGDP has not increased at a desired pace, therefore the Fed has been “tight”.

I realize you would like a futures contract and an explicit policy function by the Fed to target NGDP, thus getting market feedback. But to target NGDP doesn’t there have to be defined Fed inputs (e.g., i-rate policy, monetization policies, reserve policies, signaling policies, etc.,). etc., not just after the fact measurement that NGDP has not happened at a desired level?

What if NGDP still does not reach a desired objective after the desired inputs? Then what? Just keep doing more? From a hypothesis perspective, this reminds me of the now infamous Romer verbal construction regarding the stimulus bill which created the unfalsifiable “jobs created or saved” line quoted often by our president. It further reminds me of Krugman and his “just spend baby spend” policy prescription as the stimulus seemed to be underperforming forecasts. Further, what can be done to increase velocity, which seems important in your NGDP framework?

I am NOT saying the Fed has been easy or tight (I do not know enough). What I am asking is for an explicit policy prescription the Fed should be undertaking now. If it were to target NGDP, what actions should it take in this environment, and how would we know that NGDP targeting has anything, a little bit, or a lot to do with the economic expansion, or lack there of, that follows?

That is, what is the NGDP model?

My sense is monetary policy has limitations that NGDP targeting cannot solve. I believe fiscal, tax, and regulatory issues are dominant over a reasonably wide range of monetary policy actions.

1. March 2012 at 12:29

math,

“And think first why inflation didn’t work in Germany, Zimbabwe, Russia, etc.”

The fact that you don’t distinguish between hyperinflationary countries and countries in demand-driven recessions makes me suspect that you’re not familiar with textbook economics.

It’s not clear if your requests for information (“Show me examples where”) reflect a lack of familiarity with economic theory/history or if they’re being used as rhetorical devices. It might be more effective to abandon them in the latter case and to use a less argumentative tone in the former case.

1. March 2012 at 12:37

Mike Rulle,

I think that one of the problems is that NGDP targeters have a wide range of positions in economic theory: George Selgin is an Austrian, Scott Sumner is a Market Monetarist, Paul Krugman is a Keynesian etc. So there’s no single model that everyone is using.

The negative side of that is that the emphasis gets placed on the policy rather than the theory. There could be great empirical refutations of any one (or two) positions outlined above, and yet there would still be a case to be made for NGDP targeting. I imagine that critics of NGDP targeting sometimes feel like they’re shooting clay pigeons…

“My sense is monetary policy has limitations that NGDP targeting cannot solve. I believe fiscal, tax, and regulatory issues are dominant over a reasonably wide range of monetary policy actions.”

I actually think there’s a lot of truth in this statement. Monetary policy can’t do everything. It won’t give a country a flexible labour market. It can’t guarantee a competitive, efficient economy. It won’t solve every possible kind of debt crisis. All NGDP targeting does is prevent aggregate demand from having a long-term accelerating inflation or deflation pattern by stabilising nominal expenditure. However, as we’ve seen in the last four years, there are major gains to be made by achieving that goal.

1. March 2012 at 12:48

Math, You said;

“I understand you have no theoretical foundation behind your imaginary project.”

Then I guess you understand nothing about my project.

dwb, Unfortunately, many people think the problem is too expansionary a monetary policy.

Thanks for the link. Marcus Nunes sent me the same piece a couple years ago. If you google “Rooseveltian Resolve” you’ll find a post–also the adjacent post.

Barry, Yes, low NGDP can be caused by low V, so what?

Steve, I’m glad I don’t invest with them.

Patrick, Good suggestion, but there are some “attitudes” that are impossible to get through to.

Ben, I agree.

Math, You said;

“And think first why inflation didn’t work in Germany, Zimbabwe, Russia, etc.

Then you would think that something is wrong with the “hot potato” theory. Perhaps it is just myth, some kind of urban legend.”

The hot potato theory says more money leads to more NGDP. And you think those examples refute it?

Ravi, I’m quite sure Bernanke didn’t suddenly change his views without telling us. Imagine him saying the following:

“I used to think interest rates and the monetary aggrgetes were lousy indicators of the stance of monetary policy, but now I think they are great indicators.”

No, I can’t imagine that either.

Keep me posted on Japan.

Morgan, Cute.

Jonni, Yes, it’s about deviations from trend.

Mike, First of all, my views are just as “falsifiable” as any other macro model, which basically means not very.

I’m told that ‘falisfiability’ went out of style in epistemology several decades ago, but am certainly no expert.

The comparison you make between fiscal and monetary stimulus is completely invalid. The metaphor I use is that fiscal policy is like adding fuel to the fire and monetary policy is like adjusting the position of the steering wheel. One is costly (fuel), and one isn’t (no steering wheel setting is more costly than any other.)

If we’d been doing NGDP level targeting since 2008 the current level of NGDP would be much higher, and the current monetary base would be much lower.

Regulations affect RGDP, not NGDP. There has never been an American recession caused by regulations, with the possible exception of the secondary downturn in late 1933, if you want to call that a recession.

It’s hard to model NGDP because of the indeterminacy problem, but the basic idea is that base velocity is mostly a function of nominal interest rates, which depend heavily on current RGDP relative to trend, and future expected NGDP growth. There are other factors that play some role in velocity, such as like high MTRs, which lead to tax evasion and increased demand for cash. Of course the Fed determines the monetary base itself.

1. March 2012 at 13:16

Barry’s cooment above of;

I’ve changed my mind, even with inflation, low NGDP doesn’t tell you anything at all. It is perfectly consistent with low V rather than low M, unless you can prove low NGDP = low M you have nothing.

I think is a common misconception and so I’ve tried to defend you Scott and the MM movement as a result here…http://macromattersblog.blogspot.com/2012/03/terminal-velocity.html

1. March 2012 at 13:21

Scott,

Read what I said above about the “hot potato” theory. What I said is really based on the historic evidence. I read before about Russian experience where whole Russian industry was idle in the 90s due to its unprofitability caused by the high inflation.

Moderate inflation will make only part of the businesses unprofitable (instead of all of them as in Russia back then). But you have to account for the negative impact of inflation on the supply side as well. You can’t only look at the demand side.

“Then I guess you understand nothing about my project.”

I tried hard and still see no reason. Why should one take NGDP as a target? Why not take as a target the NGDP squared for example? I have not seen any solid theoretical explanation.

W. Peden,

Please look above.

1. March 2012 at 13:51

Scott,

I agree that the Market Monetarists have significant headway in this debate and despite the valuable input of your fellow MM bloggers you’re without doubt the one most recognised as leading that push. I’d say you’re closer than you think to having those that matter convinced on the concept. FWIW, I’d like to see you devote a bit more time to prescribing how such a policy could/should ACTUALLY be implemented in order to level target NGDP. I know you may have covered some of this before but I’ve been reading you pretty diligently (I hope) for over 2 years now and don’t really feel I have a strong sense of “what would a Sumner-led Fed do if he was put in charge tomorrow?” I know you’ve referred to the concept of NGDP futures but having been a trader in a whole range of financial futures markets for over 10 years, I’d need a lot more convincing that such a contract could a) work and b) be enough of a mechanism to transmit policy effectively. In summary, I buy the concept that looking at the (economic) world through an NGDP lens allows you to truly gauge the stance of monetary policy. It’s also clear that a lot more of the influential field is coming round to this way of thinking even if the most important (Ben) have frustratingly, moved further away. However, would now be the time to start pushing some tangible policies that could implement the framework? Both short term changes and long term ones? At the same time, it would enable you to tackle head on the few legitimate problems that the better informed critics of the approach have raised.

Anyway, keep up the great work!

1. March 2012 at 13:56

This might be a good time to take stock of the amazing recent success of market monetarism.

Now THAT’S funny. If by “amazing recent success” you mean a collapsed economy, and another false boom that is going to inevitably bust, then sure, it’s….”amazing.”

If any readers want to know what has been successful in terms of monetary matters, just take stock of gold. It has been outperforming every single fiat currency on the planet since forever.

One ounce of gold could buy the S&P500 in 1972. How much of the S&P500 can one ounce of gold buy today? The same thing.

Contrast that with the dollar, where one dollar could buy 1/100 of the S&P in 1972, whereas in 2012, one dollar can only buy 1/1400.

However “amazing” the dollar has been, gold beats it.

1. March 2012 at 14:11

math,

Nope, I don’t accept that analogy between the current US economy and an economy suffering from hyperinflation. Nor is there any reason in economic theory to do so. There is a qualitative different between an economy suffering from an aggegate demand shortage and an aggregate demand overkill; it’s not just some sort of quantitative difference.

I also don’t accept the claim that THE reason why Russian industry in the 1990s was so weak was because of high inflation.

As for inflation and the supply-side, George Selgin is a good introduction to this stuff. Inflation hurts output when there is an oversupply of money which distorts the price structure as demand overstretches the ability of producers to produce. On the flipside, a rise in the rate of inflation assists output when there is either (a) a shortfall of demand, usually caused by a monetary squeeze or (b) a shortfall of supply. In both (a) and (b), what is really going on is that higher prices offer producers an incentive to produce.

I like Selgin’s approach because it brings us back to microeconomics 101 and Hayekian price signalling: the function of prices is to co-ordinate economic activity. By allowing prices to be pushed down by a shortage of money, the Fed distorts real output just as surely as fixing an economy-wide price ceiling. A return of NGDP to a steady trend would be desirable because it would end that distortion.

Major Freedom,

“If any readers want to know what has been successful in terms of monetary matters, just take stock of gold.”

Why?

1. March 2012 at 14:47

W. Peden,

Thanks for your clever comment.

Re: Russia

It’s not my claim. This is what Russian industrialists themselves were complaining about in the Russian newspapers back then. — That their businesses had became unprofitable due to the high inflation.

Re: inflation & supply side

Two points. First, at one extreme was German industry prosperous due to lack of inflation and at the other extreme was Russian industry devastated due to the glut of inflation. So, here we have a continuum of inflation points between these two extremes and can “envision” possible impacts of different points there on the health of the supply side. Second, the main vocal point among Russian industrialists’ complaints — if I remember it right — was that inflation had actually destroyed the working capital of their corresponding businesses and made the banking loans unattainable for them.

1. March 2012 at 15:19

Math: Market Monetarists want to restore nominal gdp to 5%, not 5000% like in Wiemar Germany or Zimbabwe. It’s the difference between taking one or two aspirin to soothe your headache, and taking the whole bottle and dying.

1. March 2012 at 16:07

‘And I don’t care very much what Friedman and Schwartz said about the topic.’

Then why did you ask for ’empirics’, and say you didn’t know such circumstances in history?

‘A Monetary History’ is densely packed with just what you requested. For instance, after the end of the 1920-21 recession the money stock increased 14% in the next 22 months, and industrial production increased 63% (Net national product rose 23%) in that period.

Now you know ‘such circumstances in history’. Don’t bother to thank me.

1. March 2012 at 16:09

One ounce of gold could buy the S&P500 in 1972. How much of the S&P500 can one ounce of gold buy today? The same thing.

Contrast that with the dollar, where one dollar could buy 1/100 of the S&P in 1972, whereas in 2012, one dollar can only buy 1/1400.

first, the s&P/gold ratio has been horrendously volatile. even during the higher-than-now inflation prone 70s and 80s, gold could drop 30% in 6 months.

second, most important, why would i want a constant s&p/gold ratio???!!! thats asnine, since i want a return on equity plus something for the risk i am taking.

third, why should asian/indian jewelry supply/demand which have a large influence on gold prices, also dictate the price level in the U.S.???!!! thankfully, the gold standard will never come back in the U.S., barring maybe some apocalyptic event like massive solar flares that wipe out civilization.

1. March 2012 at 16:24

math,

Re: Russia

I don’t deny that high inflation was ONE factor in the unprofitability of Russian industry in the 1990s. I don’t think that it was a necessary factor: those rust-mills in Magnitogorsk weren’t going to suddenly become profitable if Russian inflation settled at a steady 2% with no transition costs. Less unproftible? Sure.

Re: inflation & supply side

German industry at what point in history?

1. March 2012 at 16:26

dwb,

Not to mention that, if you have a gold standard system and there are major foreign powers who don’t, then they can crash your economy through buying/selling gold. I don’t see how replacing the Federal Reserve with the Chinese Politburo is an improvement.

1. March 2012 at 16:39

@math:

I am not really sure what your concern is. ngdp targeting does not imply hyperinflation, quite the opposite. say one targets 5% ngdp. the economy (supply side) determines how much is inflation, and how much is increase in real output, and that relationship is not even constant over the business cycle. history suggests about 2% inflation and 3% growth on average but the split will vary depending on productivity growth and other things. the previous posts suggesting that you read Friedman&Schwartz are not pushing propaganda, but because they are information rich and the basis for a lot of macro work. its nearly impossible to cover everything and every question in blog format in the detail you would get in say a macro 101 class (Scott does an incredible job responding to every post despite his busy schedule and has set the bar enormously high for other bloggers, as things catch fire i think we will see an end to this, but thats a small price for success!!!!). I don’t know why you would object to perusing… i have never personally read a book, even if i disagreed vehmently, and come away regretting i read it. at least i understood the counterpoint better.

1. March 2012 at 16:56

I don’t see how replacing the Federal Reserve with the Chinese Politburo is an improvement.

probably a bad example right now. Chinese govt seems to be engineering better monetary policy than us at the moment. I’d like to replace a lot of the FOMC at the moment. If it were not for that whole, you know, civil liberties thing….

1. March 2012 at 17:22

dwb,

My point was that it’s probably not a good idea to set up a system such that any government with a strong enough capital position can bankrupt you by buying or selling gold as a means of international offence. A big gold-buying programme would be a fairly simple step to take prior to an invasion of Taiwan, for instance.

1. March 2012 at 17:44

W. Peden,

“German industry at what point in history?”

During the DM period.

1. March 2012 at 17:55

dwb,

“I am not really sure what your concern is.”

My point is that there are two economic mechanisms at work here.

The first mechanism is working through the demand side and it has a positive effect via the “hot potato” effect.

The second one is working through the supply side and it has a negative effect by making the businesses unprofitable.

And when you combine those two effects (positive and negative) together I truly believe that the total result becomes negative. Looking at the points of low inflation (Germany during the DM period) and of high inflation (Russia during the 90s for example) I see that supply side mechanism has higher impact than the demand side mechanism on the ultimate outcome.

1. March 2012 at 18:20

Morgan Warstler,

I knew of your association with Andrew Breitbart and as much as I totally despised him in life I am truly sorry to hear about his death. My prayers are with his family and friends.

Despite my personal differences I always regarded him as a friend of liberty.

1. March 2012 at 18:34

And honestly, it frightened me. I went to see my doctor today and ordered up a full set of urine and blood tests. I’m five years older than Breitbart. I’m not about to die on a sidewalk unexpectedly near my own home.

1. March 2012 at 19:02

@math

The first mechanism is working through the demand side and it has a positive effect via the “hot potato” effect.The second one is working through the supply side and it has a negative effect by making the businesses unprofitable.

ngdp targeting does not imply any level of inflation. you are right supply side productivity determines that. weve had about 4.5% ngdp growth since the early 90s, i dont think anyone ive seen is contemplating higher. so whats the issue? overall profits rise with productivity and real returns,and a stable macro growth environment encorages that.

1. March 2012 at 19:02

@math

The first mechanism is working through the demand side and it has a positive effect via the “hot potato” effect.The second one is working through the supply side and it has a negative effect by making the businesses unprofitable.

ngdp targeting does not imply any level of inflation. you are right supply side productivity determines that. weve had about 4.5% ngdp growth since the early 90s, i dont think anyone ive seen is contemplating higher. so whats the issue? overall profits rise with productivity and real returns,and a stable macro growth environment encorages that.

1. March 2012 at 19:02

@math

The first mechanism is working through the demand side and it has a positive effect via the “hot potato” effect.The second one is working through the supply side and it has a negative effect by making the businesses unprofitable.

ngdp targeting does not imply any level of inflation. you are right supply side productivity determines that. weve had about 4.5% ngdp growth since the early 90s, i dont think anyone ive seen is contemplating higher. so whats the issue? overall profits rise with productivity and real returns,and a stable macro growth environment encorages that.

1. March 2012 at 19:20

Scott,

Chest beating is deserved and (socially efficient) but still no one is coming up with a recipe for NDGP targeting that is certain to work and more or less accountable (meaning some control over redistributive effects) AND allows politicians to claim credit/make plausible promises (otherwise there is no democracy and the US is allergic to technocracy).

However, as this shows

http://ideas.repec.org/p/cpb/discus/131.html

financial crises appear to be uniformly associated with very slow recovery paths.This despite the fact that the countries in the sample must have used diverse policy solutions. That would mean to me that the policies tried in the past have consistently failed to have sufficient impact. NDGP targeting, as a new policy might work, perhaps..

1. March 2012 at 19:30

@math,

There’s so much more profitability (at least temporarily) under inflation.

You obviously have no acquintance with it.

1. March 2012 at 21:34

W. Peden:

“If any readers want to know what has been successful in terms of monetary matters, just take stock of gold.”

Why?

I explained why in the sentences that followed that comment.

dwb:

“One ounce of gold could buy the S&P500 in 1972. How much of the S&P500 can one ounce of gold buy today? The same thing.”

“Contrast that with the dollar, where one dollar could buy 1/100 of the S&P in 1972, whereas in 2012, one dollar can only buy 1/1400.”

first, the s&P/gold ratio has been horrendously volatile. even during the higher-than-now inflation prone 70s and 80s, gold could drop 30% in 6 months.

Horrendously volatile? The dollar has been MORE volatile than gold!

second, most important, why would i want a constant s&p/gold ratio???!!! thats asnine, since i want a return on equity plus something for the risk i am taking.

You misunderstand. I am not saying a constant S&P/gold ratio is the standard, or the goal, or even optimal. I am just comparing gold to the US dollar, by comparing each to the S&P, to see how they did relative to each other.

Comparing gold to the US dollar is what I am doing, because I consider gold to be the true money. I don’t consider it an investment. It only appears as an investment because the US dollar is being depreciated via inflation, and that results in more US dollars needed to buy gold.

Remember, I said “monetary matters.” I said if any readers want to know what has been successful in terms of monetary matters, than check out gold. Gold has been superior to the dollar in every way, from volatility, to long term performance (against the S&P).

Now, about the constant S&P/gold ratio. A constant S&P/gold ratio just means that if you bought gold in 1972 instead of the S&P, then by today you would have done just as well compared to if you actually bought the S&P. That’s all it means. No matter what you bought, you would have had the same return in dollars.

third, why should asian/indian jewelry supply/demand which have a large influence on gold prices, also dictate the price level in the U.S.???!!!

Why “should” it? You mean ethically? Well, why “should” the Fed determine the price level in the US? Why should prices in the US not be determined by world market conditions? Shouldn’t we be talking about world prices instead of advocating silly nationalistic mercantilist policies?

If you are willing to let supply and demand conditions of dollars in New York affect the price level in Texas, then why not let asian and indian supply and demand in dollars affect the price level in Texas, and the rest of the US?

You sound xenophobic. That’s primitive.

If gold were money, there wouldn’t be any gold “prices” the way prices are typically referred. There would only be prices of everything in terms of gold. Gold would be the standard.

Now, relating this to asian/indian jewelry in a gold standard, you are making it sound like asians and other indians are going to randomly convert the gold that they were originally using for monetary purposes, to jewelry instead. This is not what happens in practise. In practise, as the supply of gold is gradually produced, the amount of gold “in circulation” gradually increases as well.

thankfully, the gold standard will never come back in the U.S., barring maybe some apocalyptic event like massive solar flares that wipe out civilization.

Fiat money standards have never lasted for more than a generation or so. It will die and there will eventually be a free market gold standard once again. Fiat money is based on violence, and violence is always exposed, sooner or later, by the mass population. Sometimes it takes a while, but a lie cannot remain a lie forever.

1. March 2012 at 21:35

ssumner:

I’d say that market monetarism is on a roll. It’s now conventional wisdom that the Fed could have and should have done more. Not conventional wisdom among average people, but among the best and brightest in the blogosphere.

HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHA

1. March 2012 at 22:10

Major_Freedom: why should we care about the ratio of US$ to S&P or gold? I see these charts about how much value a $ has lost and then think of living standards over the same period and think, so what?

In the present situation, it seems silly to so completely prioritise the value of a unit of money over the use of money. The point of money is to facilitate transactions. Squeezing down the level of transactions in order to protect the value of money is to sacrifice the function of money to protect its price: an odd thing to do. After all, if its price is so terribly important, why would not increasing its value be the thing to do? Aim for lots of deflation, that would really increase the value of money. One could see how much “lost” value could be regained.

If one makes the level of transactions one’s target, then at least one is targeting what money is for, which is to facilitate transactions.

The general rule is, it’s transactions that matter!

Fiat money standards have never lasted for more than a generation or so. 70+ years and counting is an awfully long generation. Indeed, that is now longer than the conventional gold standard: the US was only on the gold standard from 1879-1917. About a generation, in fact.

1. March 2012 at 22:25

Mark, it was a horribly shitty day. Thx for your note.

For the record: when Matty’s dad dies I’m going to send a clown to the memorial throwing glitter and singing Andy’s name, even 40 years from now.

110% serious. He’ll learn by my hand, or apologize publicly first.

1. March 2012 at 23:41

Lorenzo from Oz:

Major_Freedom: why should we care about the ratio of US$ to S&P or gold? I see these charts about how much value a $ has lost and then think of living standards over the same period and think, so what?

Again, I was ONLY comparing the relative performance of gold vis a vis the dollar.

Living standards? Real wages have stagnated since we abandoned the gold standard in 1971:

http://www.eoionline.org/images/constantcontact/wpr/2009/fig1_ProdWages.jpg

In the present situation, it seems silly to so completely prioritise the value of a unit of money over the use of money.

In a neutral money world, you’d be right. But it’s not, so you’re not.

The point of money is to facilitate transactions. Squeezing down the level of transactions in order to protect the value of money is to sacrifice the function of money to protect its price: an odd thing to do.

“Squeezing” the level of transactions? You make it sound like people will choke on earning a gold income that grows in purchasing power. Oh no!

After all, if its price is so terribly important, why would not increasing its value be the thing to do?

Don’t look now but you just called for a gold standard to replace the fiat paper standard.

Aim for lots of deflation, that would really increase the value of money. One could see how much “lost” value could be regained.

Deflation is not “aimed” at. What is aimed at is profits, and profit seeking and increasing productivity has the benevolent side effect of falling prices and increasing purchasing power of money.

If one makes the level of transactions one’s target, then at least one is targeting what money is for, which is to facilitate transactions.

If money is only good for facilitating transactions, then there is no reason for it to be controlled by the state, nor even inflated in quantity.

The general rule is, it’s transactions that matter!

Money is not neutral!

Fiat money standards have never lasted for more than a generation or so. 70+ years and counting is an awfully long generation.

No, the fiat standard has only been around since 1971. That’s when the dollar was no longer constrained to gold in any way. That’s when the pseudo-gold standard of Bretton Woods turned into fiat.

Indeed, that is now longer than the conventional gold standard: the US was only on the gold standard from 1879-1917. About a generation, in fact.

It’s actually only been around 41 years. I submit the fiat standard burst in 2008, after 37 years, right on the historical schedule. Right now it’s on its last legs.

2. March 2012 at 01:32

Scott, for what it’s worth I think you’re right. Maybe the reason you got the impression people disagree with you is that those who agree are unlikely to crowd your comments section with “GO MARKET MONETARISTS” type of posts?

2. March 2012 at 02:33

Major Freedom,

No, you didn’t. What’s so special about gold as a measure of monetary success?

2. March 2012 at 02:37

math,

Again, the DM period is a fairly long period and it covers episodes in German history ranging from the Bretton Woods period to the serious inflation in the mid-1970s to the monetarism of the late 1970s/1980s to the botched re-unification in the early 1990s to the euro-prep period in the 1990s.

Judging from the context in your comment, however, I assume you mean some period like the 1990s when the strength of the DM hurt German industry? However, that’s not really a continuum with hyperinflation, since (1) the internal and external values of a currency are distinct and (2) a strong exchange rate tends to hurt manufacturing, at least in the short run, but hyperinflation hurts economic activity at all levels except the printing of notes.

2. March 2012 at 03:43

Major_Freedom: thinking that fiat money is on its last legs is mere supposition. Coming from a country which was on the gold standard rather longer than the US (1852-1915, 1925-1930) and has been on a fiat money standard for 82 years and going strong, I am completely unimpressed with your metrics of comparison. The A$ has varied from a low of 50cUS to its current $US1.07 in the last 12 years: this despite the RBA running slightly higher average rate of inflation than the Fed.

I infer from this, particularly the results for 2008-2012, that the RBA’s policy of getting income growth stable via an explicit target that anchors nominal expectations works much better than the Fed’s obsessing over keeping inflation down: or the BoJ or the ECB’s similar obsessions.

And because the RBA keeps nominal income growth stable based on anchoring expectations in an explicit way, it does not have to resort to various QEs that do not work because the central bank won’t set explicit targets in ways that anchor expectations.

All a gold standard is, is a way of anchoring expectations. It relies on central bank management as much as any other system. It is no accident that the country that was on the gold standard by far the longest–the United Kingdom–was also the country that pioneered central banking.

As for stagnant real wages, that has much more to do with immigration, globalisation and women entering the workforce than anything any central bank has done. Track per capita household income, it is a much more useful indicator of living standards.

2. March 2012 at 04:39

From Papola:

http://www.cbsnews.com/8334-505143_162-57343788/will-these-10-jobs-disappear-in-2012/?pageNum=9&tag=next

We see why so many economists pretend that what DeKrugman does is economics.

2. March 2012 at 06:41

Thanks Jason.

math, You seem to think the hot potato effect has something to do with RGDP growth. It doesn’t. It predicts fast NGDP growth, which did occur in those countries.

Alex, Google my post “spot the flaw in NGDP futures targeting.”

I’d set a slightly higher than 5% NGDP target for the next few years, and then 5% thereafter. I’d do level targeting. I’d commit to keep buying T-securities until NGDP expectations (either NGDP futures market or internal Fed forecast) was on target. I might cut IOR, but I doubt that would be needed.

Major Freeman, Seriously, could you be any more clueless if you tried? You are the only person in the blogosphere who thought my “success” comment referred to policy implementation, rather than intellectual success.

If you keep this up my readers will think I am paying you just to make the other side look bad.

Patrick, Thanks for that info, but you and I both know that people like math have their minds made up, When they say “show me” they don’t actually want us to show them, it would make them feel uncomfortable.

Rien, The redistributive effects of various monetary targets are vastly overrated–recall the superneutrality of money. In the short run one policy might favor one group a bit more, but it balances out. Right now monetary stimulus would help both the poor and the rich.

The financial crises literature doesn’t relate to this crisis, which is caused by low NGDP. I agree you’d expect a slow recovery from a recession caused by a financial crisis, but this recession is different. When both occur–Argentina 2002 and the US 1933, you often get fast growth as soon as NGDP starts rising fast.

Morgan, I didn’t know you were a friend of Breitbart. Sorry to hear about the news.

Orionorbit, Here’s my take. In late 2008 and early 2009 people both inside and outside the blogosphere were mostly clueless about market monetarist ideas.

2. March 2012 at 07:15

dwb,

“so whats the issue?”

Once again: the issue is that “you” (in a broad sense) want to increase inflation to have an economic expansion (through the “hot potato” theory). I am thinking that inflation will make matters worse by decimating the real economy (by making the “supply side” less profitable / more unprofitable).

2. March 2012 at 07:21

Mark A. Sadowski,

“There’s so much more profitability (at least temporarily) under inflation.”

Of course, some businesses are thriving in the inflationary environment. As we discussed above, trade was very profitable in Russia in the 90s (demand side — people were trying to spend money on anything) while almost all production was unprofitable. But the total impact of high inflation environment on Russian businesses was negative.

2. March 2012 at 07:33

W. Peden,

Nope. What I tried to say is that low inflation (or strong DM) was impacting positively the supply side of German economy and negatively the demand side of it.

But totally, German economy was healthy and prosperous, which means that (positive) supply side impact prevails over the (negative) demand side impact.

So, this fact has reinforced my point that supply side impact tends to be stronger than demand side impact w.r.t. inflation (looking at historic examples from both German and Russian economies).

Regards

2. March 2012 at 07:44

@math

Once again: the issue is that “you” (in a broad sense) want to increase inflation to have an economic expansion (through the “hot potato” theory).

nope. wrong on all counts (please don’t tell me what i “want”!). not interested in higher inflation. nor do i see how that could be so in the long run. the “hot potato theory” or quantity theory of money merely states that increasing the monetary base $1 will increase nominal gdp by more than $1. It does not state how much will bleed into inflation and how much into real output.

Moreover, I think that stable ngdp would lower trend inflation from 2% to maybe 1%. one key reason the FOMC targeted 2% inflation is to provide a buffer against deflation. A far better buffer against deflation is to maintain aggregate demand by keeping ngdp constant – which means the deflation insurance premium built into the 2% could be eliminated.

2. March 2012 at 07:46

Scott,

“It predicts fast NGDP growth, which did occur in those countries.”

I’m not sure there was a NDGP growth in countries with high inflation.

Are you sure about this? Prices were rising, production was plummeting. I’m not sure what the total quantitative effect was but I doubt very much your conclusion. If one multiplies zero (production) by any big number (inflationary price) the ultimate result will still be zero.

2. March 2012 at 07:56

dwb,

“increasing the monetary base $1 will increase nominal gdp by more than $1.”

Is it a hypothesis or a fact? I can’t see how devastating production to the ground can produce a positive effect. As I said above to Scott, “if one multiplies zero (production) by any big number (inflationary price) the ultimate result will still be zero.”

2. March 2012 at 07:56

math,

NGDP is the sum of real gdp + inflation (well, strictly speaking, real gdp is a constructed statistic from NGDP deflated by a price index, but the maths works both ways) not real gdp * inflation.

2. March 2012 at 08:00

math,

I don’t think that the continuum is between, say, Germany in the 1980s to Russia in the 1990s. A good example of demand-side deflation having negative supply-side effects is the Great Depression. A good example of demand-side inflation having negative supply-side is indeed Russia in the 1990s (or Zimbabwe or Germany in the 1920s or basically any period of hyperinflation or high inflation).

Between those two extremes lie a number of alternatives. If prosperity could be bought by having a strong currency and/or deflation, there would be far more countries pursuing such policies.

2. March 2012 at 08:09

W. Peden,

RGDP = Y * P’

NDGP = Y * P

Y – production,

P – inflationary price

P’ – adjusted price

But we still have a multiplication. One can’t add inflation to RGDP (since they have different units of measurement).

2. March 2012 at 08:10

@math:

this is a fact. devastating production to the ground?? wha?? wikipedia the quantity theory of money. lookup and plot the “velocity of money” in FRED along with the monetary base and gdp. i invite you to research the phillips curve as well. there are a couple of good fed staff papers on the effects of QE. my advice is dont bring a knife to a gunfight, do some research.on your own.

2. March 2012 at 08:30

W. Peden,

I can’t talk about Great Depression here. First, I have no first hand knowledge of it. Second, I held rather unconventional view of its reasons (following earlier views by Marriner Eccles and trying to extend them up to the current Recession), which I don’t want to discuss here currently.

W.r.t. the “continuum,” of course one can envision different kinds of it. I have built one for the narrow purpose: discuss how different levels of inflation have an impact on businesses engaged in the production activities.

2. March 2012 at 08:37

dwb,

So, it’s a hypothesis, which is probably wrong.

I have to build a math model to verify it but my intuition tells me that (since the rate of production change ordinary exceeds the rate of price change).

2. March 2012 at 09:19

@Scott

“Barry, Yes, low NGDP can be caused by low V, so what?”

So how do you know it wasn’t low V rather than low M (tight money) that caused low NGDP over the last few years?

2. March 2012 at 09:23

So, it’s a hypothesis, which is probably wrong.

no, more like a definition. when you can prove x% nominal gdp targeting results in long term inflation greater than x% post a link to your thesis. your “intuition” is wrong.

2. March 2012 at 09:54

dwb,

So, it works this way:

Y0 – production before change (i.e., FED’s action)

P0 – price before change

Y1 = (Y0 – dY) – production after change

P1 = (P0 + dP) – price after change

Y1*P1-Y0*P0=Y0*dP-dY*P1

Thus,

if dP/dY>P1/Y0 => NGDP grows

if dP/dY NGDP falls

You are partially right. My intuition was wrong. Result depends on the levels of production and price (not only on the rates of changes for the production and price as I was thinking).

To build an elaborate model, I need to spend more time (which I don’t have) and effort (which I actually don’t really want to do).

2. March 2012 at 09:56

Erratum:

if dP/dY>P1/Y0 => NGDP grows

if dP/dY NGDP falls

2. March 2012 at 09:58

Something is strange with website here:

if dP/dY is less than P1/Y0 then NGDP falls

2. March 2012 at 10:08

dwb,

It’s better to rewrite it as follows:

dP/P1>dY/Y0 => NGDP grows

dY/Y0>dP/P1 => NGDP falls

So, my intuition was almost right 🙂

2. March 2012 at 11:16

@math:

you are missing the larger point(and some minus signs), and still no. first, ngdp is held constant. second, whats the mechanism for determining inflation or output growth (wheres technology and population growth? wheres price or wage stickiness or lack therof?). why is output growth higher than inflation/deflation or vice versa? if ngdp grows $1 how is that split between Y and P? wheres the connection to money??

2. March 2012 at 11:40

dwb,

Which minus signs? Where?

I said it’s not elaborate model. Treat it as a simple exercise on the topic.

2. March 2012 at 13:36

if inflation (dP/P>0) is greater than the decline in real output (dY/Y<=0), ngdp increases. conversely, if deflation (dP/P<0) is greater than the increase in real output (dY/Y) ngdp decreases. your signs are off. anyway, its more clear to do it in logs. This is not a model, its barely albebra. A model would have a mechanism for wages&prices, bonds or money, and some process for technology or productivity to even start to be a simple model, and would make a prediction as to what would happen if money base went up $1.

2. March 2012 at 13:52

dwb,

Nope. You didn’t pay attention.

I made all variables positive on purpose. So, I adjusted the signs correspondingly. And I considered (positive) inflation.

dP, dY > 0

I have a different model in mind from one that you have described. It’s much more conceptually difficult to do it right than that.

2. March 2012 at 15:18

let me know how that works out for you.

2. March 2012 at 15:39

dwb,

I’d love to but …

1. I’m not regular to this site.

2. I have many other things in my life in order to dedicate much time and energy to this task.

3. I have no clear step-by-step picture in my mind at this moment how to build this model in the way I’d like it. Perhaps, I can’t do it at all. Sometimes you just can’t solve the complex problem due to the lack of talent.

2. March 2012 at 17:55

Math, You said;

Are you sure about this? Prices were rising, production was plummeting.”

I’m going to assume you are kidding, it’s too painful to think you might not know NGDP in Germany and Zimbabwe rose more than 100 billion percent. NGDP always rises during hyperinflation.

You said;

“But we still have a multiplication. One can’t add inflation to RGDP (since they have different units of measurement).”

No one adds inflation to RGDP, they add inflation to the growth rate of RGDP (both are percentages.)

Barry, I don’t define “tight money” as falling money supply, I define it as falling NGDP expectations. Ben Bernanke and I agree on that point. It makes no difference to me whether NGDP falls because of V or M, the effect is the same. The Fed needs to keep NGDP from falling.

2. March 2012 at 19:36

Scott,

1.It is your view that this is not a financial crisis. That is not a consensus view.

2. Mechanisms to manage NDGP -yet to be created (your futures are a sketch, not even a design or a prototype, let alone something that could be used immediately within the accountability environment of a democracy’s central bank ) My point about redistribution was merely that once you start leaving existing institutional paths you are bound to get strong redistributive effects (unlike when you use traditional monetary policy through existing institutional structures). Just a look at the most recent incarnation of ECB QE using bank loans as collateral shows how much that could alter the competitive environment and save firms (clients of weak banks) about to go bankrupt thus causing their better funded competitors an unfair disadvantage. Much worse could happen should innovative monetary policy produce unexpected expernalities of a redistibutive type. My point was merely to draw attention to the micro, legal and finance issues that macro economists easily ignore when designing but politicians should take into account when choosing and implementing. The difference between a technocratic approach and a democratic one.

The NDGP targeting cause would benefit from scholars working on developing the idea from an obviously worthy aim towards a reasonably reliable policy repertoire.

You may argue that all (?) of the major innovations in economic policy were introduced in periods of economic trauma of large scale social change. Those circumstances would not favor incremental change or careful step by step progress from idea to functioning process. But maybe there are ways to put this idea into practice without it being like the desperate behaviour of someone who has seen everything else fail to cure the condition.

I added this link simply to illustrate the point that possibly, there are no policy remedies for financial crisis-induced (or boosted) recessions and that all we see is politicians and technocrats (central bankers) running around and acting out remedial action, without much conviction that “macro” will benefit, but making sure their personal mandate is protected as much as possible.

3. March 2012 at 05:46

@Scott

“Barry, I don’t define “tight money” as falling money supply, I define it as falling NGDP expectations. Ben Bernanke and I agree on that point. It makes no difference to me whether NGDP falls because of V or M, the effect is the same. The Fed needs to keep NGDP from falling.”

But this is becoming circular again, almost nobody else defines tight money this way. Of course falling NGDP expectations will cause falling NGDP, that’s a much less profound statement than saying tight money caused the recent drop in NGDP to someone unaware of your definition of tight money. It’s also unclear how the fed can do anything about a low V problem.

3. March 2012 at 09:49

Scott,

“I’m going to assume you are kidding, it’s too painful to think you might not know NGDP in Germany and Zimbabwe rose more than 100 billion percent.”

I’m a mathematician. I don’t always follow your dirty tricks.

“NGDP always rises during hyperinflation.”

1. It’s probably due to its calculations. It takes into account import. So, if you completely destroy your own production, import multiplied by the inflationary price will give you a NGDP growth.

But from a practical point of view, this policy is totally detrimental. You completely annihilate your own production, create the nation of unemployed but still have a NGDP growth (due to the way this animal is calculated).

2. Some additional considerations. There are always some kinds of production, which will never be completely destroyed — agricultural business for example. But the farmer will refuse to exchange their products for worthless money. So, shadow economic activities will flourish.

It will create a moneyless economy (a.k.a. barter). Authorities will lose control over market economy there and will have to use depression against reluctant market participants.

“No one adds inflation to RGDP, they add inflation to the growth rate of RGDP (both are percentages.)”

It works only with small values. So, you have to be careful here.

Here is an explanation:

(1+dA)*(1+dB)=1+dA+dB+dA*dB

If dA and dB are small the term dA*dB can be discarded.

So, (1+dA)*(1+dB)-1=dA+dB (for small values dA and dB only)

3. March 2012 at 10:46

Errata:

depression -> repression

Authorities will lose control over market economy there and will have to use REPRESSION against reluctant market participants.

3. March 2012 at 17:29

Rien You said;

“Just a look at the most recent incarnation of ECB QE using bank loans as collateral shows how much that could alter the competitive environment and save firms (clients of weak banks) about to go bankrupt thus causing their better funded competitors an unfair disadvantage.”

We are talking past each other. You seem to assume that what’s going on there is the sort of thing I favor. No, I favor NGDP level targeting, with or without the futures add on (which I agree won’t happen soon.) But NGDP targeting itself is very plausible. Australia is much closer to what I favor than Europe, and they aren’t doing any “unconventional policies” as far as I know.

I recently proposed a far more “acceptable” version of my plan, which looks very similar to inflation targeting. There are ways to move in this direction if we are serious. It’s up to the economics profession to lead the way, so far they’ve been the problem, not the solution. How can we expect our leaders to do the right thing if economists can’t figure out what’s gone wrong?

Barry, You said;

“But this is becoming circular again, almost nobody else defines tight money this way.”

I’d say Bernanke is a pretty important nobody. But it’s also true that few economists think M is a reliable indicator of monetary policy, at least since the early 1980s when it was widely discredited. Ditto for interest rates. So what’s your bright idea?

Of course monetary policy can offset V, unless they ran out of paper and green ink.

Math, You said;

“I’m a mathematician. I don’t always follow your dirty tricks.”

OK, you are a mathematician who knows little about economics. Nothing wrong with that. But then what makes you think you can come over here with an attitude and tell those of us that have devoted our whole adult lives to studying monetary economics that we are ignorant and you are the expert?

And yes, I know that adding percentages is an approximation, I learned that 35 years ago. Economists generally deal with first differences of logs–as a mathematician you should at least understand that.

3. March 2012 at 19:15

Scott,

I know enough about economics to make my judgement about the matter. I don’t want to fight with you here. It’s your home.

Ciao

4. March 2012 at 07:07

@math

1. The argument that ngdp targeting results in hyperinflation is novel. By novel, i mean i have only seen you make this argument. I have not even seen the most ardent critics of ngdp targeting make this argument.

i feel repetitive here, but IMO ngdp targeting by definition constrains inflation. if the ngdp target is x% growth, inflation can be no more than x% as a long run trend, provided productivity and population growth are positive.

2. If you want to know what I think a math model is, please go read Sargent’s “Dynamic Macro Theory,” Stokey/Lucas “Recursive Methods in Economic Dynamics” or something of that ilk to get a flavor for math methods in Econ. If you are half the mathematician you say you are, with any economic judgement, it should be easy for you. I am not endorsing anything in these texts, but is a sampler.

can’t do anything new unless you know whats already been done.

3. Once you have done #2 and have created your hyperinflation model with devastating production, please send a link to your very long thesis with proofs. Love to see it.

4. there are lots of economists and quant finance people who are good mathematicians. You may not realize this, but many economists came in through physics, math, or other quant areas.

so, time to shut and prove it!

4. March 2012 at 09:13

dwb,

1. I have not said that. I don’t know if that is true. I said I don’t want to treat NGDP as a “holy cow,” since its blind targeting can lead to adverse results due to its composition.

2. I wrote a book few years ago about a few math models I had developed in my spare time (want to stay anonymous in this regard). So, I have my own educated opinion about the matter.

My opinion: Currently economics is in a pre-science status by being a primitive descriptive discipline and what is done there will be in the dustbin of history soon (I hope). It can’t provide answers to the modern day challenges. Models similar to what I have developed and others can make to be elements of the future economic science and will be studied by the students. Modern economists are impotents from a practical point of view who can’t do anything significant but only argue with each other and waste the societal energy.

I have to say good bye. I have more important things to do than arguing with economists here.

Regards

4. March 2012 at 17:37

W. Peden:

No, you didn’t.

Yes, I did W. Peden. I said:

“It has been outperforming every single fiat currency on the planet since forever.”

“One ounce of gold could buy the S&P500 in 1972. How much of the S&P500 can one ounce of gold buy today? The same thing. Contrast that with the dollar, where one dollar could buy 1/100 of the S&P in 1972, whereas in 2012, one dollar can only buy 1/1400.”

“However “amazing” the dollar has been, gold beats it.”

This is a comparison of gold to the US dollar.

What’s so special about gold as a measure of monetary success?

Its performance relative to the dollar in terms of volatility and return. Gold outperformed the dollar in terms of volatility, and purchasing power (return).

Lorenzo from Oz:

Major_Freedom: thinking that fiat money is on its last legs is mere supposition. Coming from a country which was on the gold standard rather longer than the US (1852-1915, 1925-1930) and has been on a fiat money standard for 82 years and going strong, I am completely unimpressed with your metrics of comparison. The A$ has varied from a low of 50cUS to its current $US1.07 in the last 12 years: this despite the RBA running slightly higher average rate of inflation than the Fed.

We’ve only been on a fiat standard since 1971, when the last link to gold was dropped. Prior to that, dating back to 1913, there was some constraint to fiat money production.

All a gold standard is, is a way of anchoring expectations. It relies on central bank management as much as any other system. It is no accident that the country that was on the gold standard by far the longest-the United Kingdom-was also the country that pioneered central banking.

Gold is more than mere expectations. It constrains the growth of the state far more than a central banking fiat standard can. It minimizes the business cycle.

You’re point about the UK being the longest on gold and the country that pioneered central banking, is in fact an accident.

As for stagnant real wages, that has much more to do with immigration, globalisation and women entering the workforce than anything any central bank has done.

Immigration, globalization, and women entering the work force, all three of these things, INCREASE the productivity of labor in a market society. They allow for more specialization, more extent of division of labor, more labor to capital. These are exactly the opposite to reducing real wages.

Track per capita household income, it is a much more useful indicator of living standards.

Real wages already subsumes this.

4. March 2012 at 17:45

ssumner:

Major Freeman, Seriously, could you be any more clueless if you tried? You are the only person in the blogosphere who thought my “success” comment referred to policy implementation, rather than intellectual success.

You misunderstand. I said “If by ‘success’ you mean…”, to make a point on the failure of market monetarism in practise. I said “if” as a purposeful conditional, not an accusation of how you interpret the meaning of “success.”

The success of a theory is properly measured by the practical outcome of the theory, not by how many people believe the theory. In practice, market monetarism has been a failure. To call it a success because more people believe it, is like calling fascism a “success” in the early 20th century because more people believed in it.

If you keep this up my readers will think I am paying you just to make the other side look bad.

You couldn’t afford me.

4. March 2012 at 21:08

Major, You said;

“You misunderstand. I said “If by ‘success’ you mean…”, to make a point on the failure of market monetarism in practise.”

That’s right Major, I’ve spent the last three years here praising the Fed for doing exactly what I wanted, the biggest fall in NGDP since 1938. Right out of the MM playbook.

5. March 2012 at 10:45

That’s right Major, I’ve spent the last three years here praising the Fed for doing exactly what I wanted, the biggest fall in NGDP since 1938. Right out of the MM playbook.

I was talking about PRIOR to 2008, when market monetarists got what they wanted, and the result was massive distortions in the capital structure of the economy.

If you got your wish of 5% NGDP inflation prior and post 2008, the results would have been even worse.

You’re attributing the failure of the economy as not practising NGDP targeting, when in reality the economy tanked precisely because we were so close to it.

5. March 2012 at 17:44

Major, Why not blame us for 9/11 while you are at it.

In the 1800s the small government types got what they wanted, and we had slavery. Was small government to blame?

5. March 2012 at 22:04

Ngdp level targeting distributes risk between debtors and creditors optimally, thus enhancing the financial stability for any given debt to gdp ratio. Lars has blogged this a couple of times.

Highly levered firms should start adding ngdp indexing clauses to their debt contracts.

Today, when there are mountains of debt, market monetarism is essential.

5. March 2012 at 22:25

@Rien

Draghi stimulus has only partially reversed the financial problems that were tripled by the deflationary errors of Trichet. BTW I do not deny that the part of the problem is real and has nothing to do with ngdp.

Please note that Draghi loan auctions are very safe, if the market value of collateral drops, banks have to post more collateral.

6. March 2012 at 05:06

This very discussion means that Scott is right about MM gaining intellectual influence. It almost seems as if some major MM blogpost was mentioned somewhere on mises.org and now its readers are here on a mission to spread the truth among unbelievers who have never heared about the tragic fate people from Zimbabwe and Weimar Germany. Yes, this is about you “math”.

Anyways, please keep these blogs comming, I know that there is a lot of people like me who learned a lot from your blogs and from excellent discussion by some people here who actually make an effort to think about what they are saying.

6. March 2012 at 06:11

ssumner:

Major, Why not blame us for 9/11 while you are at it.

“Us”? I don’t know what you mean by that. But I do know that the science leads to 9/11 being a controlled demolition. I am not blaming anyone in particular, but that’s what the science shows.

In the 1800s the small government types got what they wanted, and we had slavery. Was small government to blame?

Epic non sequitur. Now you’re just desperate. Which is good actually, because the more desperate you get, the more shaky your worldview is exposed as being. You sugar coat a lot of things you say, but underneath it is rotten to the core. That’s what you get for a Federal Reserve financed “education.”

At any rate, about that non sequitur. One might as well say that you market monetarists got what you wanted in the early 20th century with worldwide central banking, and then we had communism and fascism and slave labor camps.

Small government didn’t lead to slavery and central banking didn’t lead to slavery, despite slavery being present in both scenarios. This is absolutely ridiculous. Playing the slave card? Really?

There was slavery in “big” government countries too, but you don’t see me making such absurd leaps of logic.

We had slavery not because of small government, we had slavery because of the prevailing morality that slavery was justified. In Europe slavery ended by a moral movement that saw slaves buying their freedom. It wasn’t because government “got bigger.” They avoided a civil war. The US could have done that as well.