A wise owl

I was sad to see that James Bullard is retiring from his position as president of the St. Louis Fed. He was a fan of NGDP level targeting, and as David Andolfatto points out he was willing to dissent in both dovish and hawkish directions. He will be missed.

I don’t like monetary policy hawks and doves. Policy should be expansionary at some times (e.g., when I started blogging) and contractionary at others (right now.) Bullard understood this.

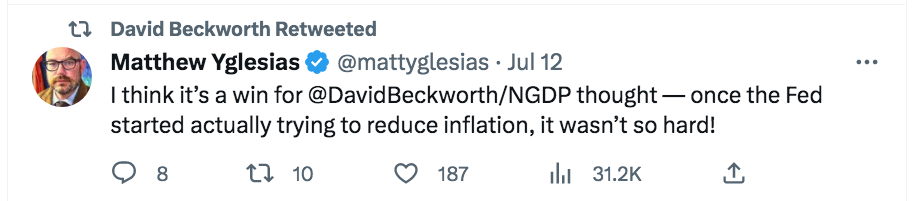

David Beckworth directed me to these tweets:

I’ve always been skeptical of the economic slack theory of inflation. There’s no way FDR could have generated high inflation in 1933 if the slack theory were true. I see inflation as being driven by changes in NGDP growth (monetary policy), and slack is something that happens if NGDP decelerates too rapidly.

But so far, NGDP growth has not decelerated too rapidly, indeed I’ve argued it’s decelerated too slowly. Even so, far worse things could have happened, and in the past often did happen. Fed policy during late 2021 and early 2022 was really bad (after being good in 2020 and early 2021)—since then it’s been average. It’s decelerated, which is appropriate—but a bit too slowly. Let’s see what Q2 looks like.

Matt Yglesias is correct that the recent strength of the economy supports the NGDP view over the slack view:

I think that’s right. But we need to be careful here, as most of the hard part still lies ahead. The Fed needs to bring down wage inflation, and before it’s all over Krugman may end up being correct. Slack doesn’t cause lower inflation, but it’s usually a side effect of wage disinflation.

Victory would be getting back to 2% with only a small increase in slack. I discuss this in a recent post on the difficulty of achieving a soft landing.

Tags:

14. July 2023 at 08:32

Who has the best explanations of how and why lower demand can sometimes result in lower output versus lower prices/lower inflation, or a mix of those two?

14. July 2023 at 10:47

re: “slack is something that happens if NGDP decelerates too rapidly”

There’s a difference between the supply of money and the supply of loan funds. And loan funds may be composed of either bank or nonbank credit.

“Slack” or capacity that exceeds demand, occurs with disintermediation of the nonbanks.

14. July 2023 at 10:54

The “ripple” effect between money and savings is diametrically opposed. The activation of savings products produces higher and firmer real rates of interest, i.e., raises r-star.

14. July 2023 at 11:02

Bill, I suppose it depends partly on whether the slowdown is expected or unexpected. Also the degree of wage stickiness.

14. July 2023 at 12:28

Thanks

14. July 2023 at 12:57

I wish Mr. Bullard a long life and happy retirement, but given money is largely neutral short term and long, it reminds me of the quip, inspired by Thomas Kuhn, that progress is measured “one funeral at a time”. Youth today believe in data, not metaphysics and word salads of the kind Scott’s generation produced. The Fed reacts to the marketplace. NGDPLT is metaphysical nonsense.

14. July 2023 at 14:16

re: “NGDPLT is metaphysical nonsense”

Actually, it’s very old school and long forgotten.

14. July 2023 at 14:22

Princeton Professor Dr. Lester V. Chandler, Ph.D., Economics Yale (per the NYT “a monetary expert”).

Chandler’s theoretical explanation was:

“that monetary policy has as an objective a certain level of spending for N-gDp and that a growth in interest-bearing deposits in the payment’s system involves a decrease in the demand for money balances, and that this shift will be reflected in an offsetting increase in the velocity of the remaining transaction’s deposits”.

N-gDp targeting would have stopped C-19 inflation dead in its tracks.

14. July 2023 at 15:54

Orthodox macroeconomists spend large chunks of their life talking about inflation.

But in the US, macroeconomists should spend a large chunk of their life talking about how to expand the house supply.

Moderate rates of inflation are not that important.

14. July 2023 at 17:29

Yeah…but again you don’t need the Federal Reserve to lower inflation or nominal wages.

It’s rather strange to study a science that is the cause of the effect, then seek the reverse cause to that effect.

Your tools for expansion just move money to inefficient and unproductive sources through fiscal stimulus, then your contraction tools break the “too big too fail” (overextended credit, bad investments) causing more stimulus: (money to save the unproductive and inefficient). The market can do all of this, and do it more productively and efficiently, without any intervention.

And the growth rates are not sustainable because you are using a credit card to run your business. When the credit dries up, you won’t have the capital injection for growth. Countries with little debt like Russia, who live within their means, and who have high rates of savings, and therefore real investment (not credit investment) are poised for a strong 21st century.

Others will see a massive decline in the value of their currency over this period of time, and probably civil war as the countries social benefit programs, influx of migrants who cannot assimilate culturally, and job loss increase significantly.

14. July 2023 at 19:57

Solon, you are correct. There was a time when housing was treated like most other consumption goods. We can find much fault in official policy–racism, sprawl, a fetish for single family dwellings, etc…but value was placed on unit production that matched population growth.

The durability of American homes was never much good, but that was by choice. We could have an aspirational system of housing production, with a mortgage system matched to various income levels.

Now, the single family suburbs have attained a quality of sacred permanence. The somewhat harmless fetish for the single family house has been elevated to the status of a powerful totem–a vehicle for capital growth that vastly exceeds the cheap lumber from which it is assembled, or the floodplain that it occupies. Protected by arcane religious scriptures called Zoning Bylaws, these objects hold a value that amazes and blinds us a nation.

Economists seem to have had considerable trouble grasping what housing actually signifies and the distortions that have been caused by a combination of perverse regulations. Case and Schiller made a simple, but deeply misleading, graph of our collective madness, but as far as I know they never questioned the underlying machinery. The misguided idea that housing is different from everything else that we consume is a dangerous condition that requires a long, slow, and probably brutal cure.

14. July 2023 at 20:01

I’ve been characterized here before as a dove. I don’t see myself that way, but accept that I may have a bias. That said, here’s a case again, for why the ~4% NGDP growth trend line is not a good one for determining the stance of recent monetary policy.

From 2007, when S&P 500 earnings reached what was then an all-time high, until late 2019, when Earnings hit another all-time high, earnings only increased by a bit over 30%, while the 10 year Treasury rate, for example, fell by over 60%. However, the S&P 500 index more than doubled over this period. This indicates that the fall in interest rates doesn’t come close to accounting for all of the appreciation of the S&P 500 index over this period. I think it indicates that there was expected additional catch-up NGDP growth as the US economy slowly approached equilibrium, even as late as early 2020, just before the pandemic. Even that late, relatively lower rates couldn’t explain S&P 500 levels.

In the longer run, the mean S&P 500 earnings yield and the mean US NGDP growth rate are equal, which I take as an indication that the S&P 500 index can be a good proxy for mean expected NGDP growth. The fact that stock buybacks increased significantly over this period also supports this view. I view divergences in the mean S&P 500 earnings yield and the mean US NGDP growth rate as an indicator of macro disequilibrium.

Alternative explanations for the higher expected earnings growth over this period include increased pricing power for S&P 500 firms. This idea seems plausible for companies like Apple or Google, for example, but to the degree it’s claimed to apply to the index as a whole, it would represent a historical departure in terms of the average S&P 500 earnings yield versus the average NGDP growth rate, to the degree it persists. This doesn’t seem like a good bet to me, and also, such a claim about pricing power requires evidence.

Hence, I’ve been writing for sometime now that I expect inflation to come down gradually over a few years or so, as supply-side shocks subside, despite NGDP being above the previous long-run growth path. I think the evidence is supporting my view, though it is still too early to declare victory.

I remind those reading, however, that I also predicted for years that the natural unemployment rate was significantly lower than most economists estimated, and that turned out to be right.

This doesn’t mean I’m absolutely correct, but so far no one has demonstrated I’m absolutely incorrect either.

15. July 2023 at 05:20

Perhaps Prof. Krugman should bear in mind a wider array of textbooks.

16. July 2023 at 07:32

@MS – “I’ve been characterized here before as a dove” – nobody cares. Are you prominent? Still nobody cares. What’s amusing reading your prolix prose is that you actually think the Fed steers the economy. That’s about as funny as the guy the other day I was talking to that believes in the Illuminati and was telling me about their machinations. The best that can be said about you, MS, is that you are being fooled by randomness. Money is everywhere and always a neutral phenomena.

16. July 2023 at 09:46

@ Ray Lopez: “Money is everywhere and always a neutral phenomena”

You’re dead wrong, as I predicted both the flash crash in stocks and bonds 6 months in advance and within one day.

17. July 2023 at 05:17

The problem is one of solidarity and pricing.

Why should the farmer work five days a week if you won’t? Why shouldn’t the improvements in productivity accrue to the farmer and they stop producing after four days work and take Friday’s off.

For the farmer to work that final day, producing the surplus for those who are currently unemployed, they need to see something in return. That’s other people working about as much as they do.

Moreover the Job Guarantee *sets the base price of the labour hour in the economy from which all other prices are derived*. It is the anchor, of the anchorism within MMT.

If I give you 10 of my notes, you have absolutely no idea how much they are worth or how many Big Macs they will buy. But if I tell you you get those 10 notes for five hours work, you will be able to gauge quickly how much a Big Mac should be in my notes. Therefore you’ll tend not to overpay.

That anchors inflation. Everybody knows how much a labour hour is worth at base, and that then *replaces* interest rate adjustments as stabilisation policy in the economy. We move stabilisation from the market for money to the market for labour.

22. July 2023 at 07:01

Shadowstats is apropos: “inflation pressures continued surface, with the May 2023 Money Supply reflecting still-extreme flight to liquidity. The most-liquid “Basic M1” (Currency-plus-Demand Deposits) held 119.2% above its Pre-Pandemic Level and was increasing year-to-year with intensifying inflation pressure, versus the Aggregate M2 Money Supply holding up by 34.7%, but declining year-to-year, amidst no signs of an overheating economy.”

The percentage of transaction’s deposits to gated deposits continues to grow. The turnover ratio for transaction accounts is much, much, higher than gated deposits. The conversion from gated deposits to transaction’s deposits should continue until M2/GDP falls back to its prior trend line.

Link: https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/economic-letter/2023/may/rise-and-fall-of-pandemic-excess-savings/

“aggregate excess savings would likely continue to support household spending at least into the fourth quarter of 2023.”

22. July 2023 at 23:24

@Kester how is this supposed to work in practice? Is the Job guarantee just like a list of temporary tasks at City Hall that anyone can complete for pay, sort of like a public sector taskrabbit? Or is it that the jobs are meant to be part of the regular civil service and a kind of career in themselves?

23. July 2023 at 03:49

Contrary to Dr. George Selgin, banks don’t lend deposits. Deposits are the result of lending/investing.

There is a one-to-one correspondence between interest-bearing time deposits and demand deposits, as time deposits grow, demand deposits shrink pari-passu and vice versa.

Ergo, M2 is mud pie.

23. July 2023 at 03:54

re: “spencerYour comment is awaiting moderation.”

Funny, because that’s exactly how we got into this predicament. The economists which debated the issue were paid not to further participate in the discussion.