Greetings from the middle of nowhere

I am 12 days into 19-day trip to New Zealand. Everything here is upside down. They drive on the left and celebrate Christmas on a hot summer day. Even the moon is upside down, with the brighter portion at the top. (Orion’s sword hangs upward.)

I don’t have much to say about the NZ economy, other than that everything seems fine. This country doesn’t seem to have any serious problems, at least that are apparent to tourists. (I imagine that the locals would find plenty to complain about.)

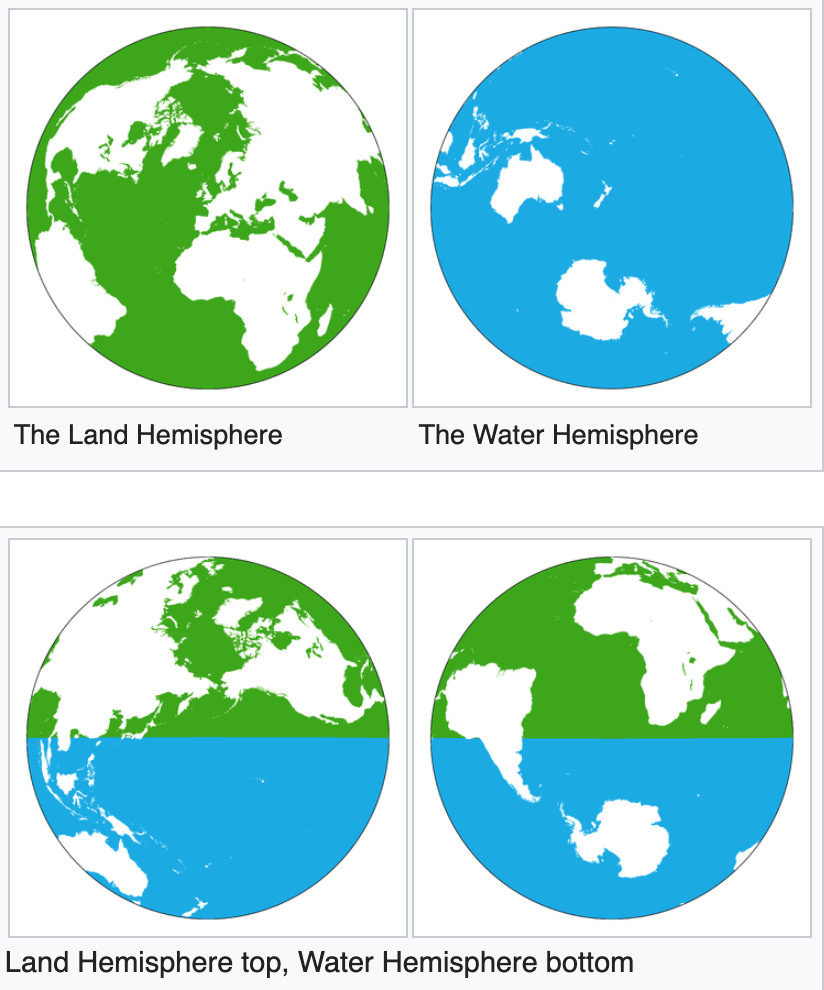

Astronomers tell us that no one place is the center of the universe, or perhaps that each place is equally in the center. That’s not true of Earth, where London is near the center and New Zealand is in the middle of nowhere. It might help to examine the “land hemisphere” and the “water hemisphere”, defined as the hemispheres that contain the most and least amount of land:

Notice that New Zealand is near the center of the water hemisphere. Its closest significant neighbors are Australia, which has fewer people than metro Tokyo, and Antartica, which has some penguins. North of the 38th parallel, the northern hemisphere is full of big cities like Beijing, Rome, London and New York. South of the 38th in the southern hemisphere you have Wellington and Christchurch. That’s it. It’s lonely down here.

Some random observations:

1. Prices seem lower here (compared to the US), except for gasoline. Houses are also expensive. Living standards seem a bit lower, but there are many intangibles in favor of New Zealand (weather, informal culture, trust, lack of congestion, personal freedom, etc.)

2. There seem to be more cows and fewer sheep than during my previous trip (in 1991).

3. Auckland seems like a smaller Sydney. It has a new district along the waterfront that is similar to San Francisco’s SoMa and Boston’s South Seaport. There is good art deco architecture throughout New Zealand.

4. Domestic flights are convenient and very cheap.

5. Wellington seems like a small big city. The national capital area is utterly unpretentious, with a child’s playground right in front of the Parliament building, and an ordinary suburban residential area right behind it. I wish America behaved more like New Zealand.

6. Lots of stuff is free (museums, national parks, etc.) Much less security than in the US, and much, much, much less than in China. In many ways, New Zealand seems almost the exact opposite of China. BTW, New Zealand is about 5% Chinese and 5% Indian, much higher percentages than in the US.

7. The drinking age is 18, and smoking is allowed in more places than in the US. Prostitution is legal. There are far fewer frivolous lawsuits and hence people are freer to do fun things that are risky. There are fewer walls than in the US, and much, much much fewer than in China. You can pretty much roam around wherever you wish. It is number 3 in both the Fraser and Heritage Economic Freedom Indices, and when you add in politics it may well be the freest country on Earth.

8. Pound for pound, it might be the most scenic country in the world, at least the developed world. There is an enormous variety of interesting scenery. It’s also very easy to get around. The roads are not crowded (outside a few cities) and parking is not an issue. Unfortunately, the glaciers are receding fast.

9. They have the sort of agricultural productivity that was very valuable throughout most of human history. Unfortunately, it’s Australia that has the resources that are valuable today (iron, coal, gas, etc.) This is one reason why Australia is richer. They also lack economies of scale. Americans wrongly think the rest of the world is hurting us with unfair trade practices, but New Zealand really is hurt badly by the unfair trade practices of others (which protect farmers in rich countries.)

10. They have fewer than 5 million people in a country 10% bigger than the UK and 30% smaller than Japan. (Physically speaking, New Zealand is a bit like Japan.) Their population has recently been growing at 2%, which is perhaps the fastest rate for any developed country? Their bigger cities seem to have the same restrictive zoning problem as in Australia and Canada, keeping house prices high.

People often think of paradise in terms of tropical islands in the South Pacific, such as Tahiti and Bora Bora. Perhaps temperate New Zealand is the the real paradise.