What I’ve been reading

The Mercatus Center has a new paper by Stephen Matteo Miller and

Thandinkosi Ndhlela, which examines the Zimbabwe hyperinflation. Here is the abstract:

Unlike most hyperinflations, during Zimbabwe’s recent hyperinflation, as in Revolutionary France, the currency ended before the regime. The empirical results here suggest that the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe operated on the correct side of the inflation tax Laffer curve before abandoning the currency. Estimates of the seignorage maximizing rate derive from a short-run structural vector autoregression framework using monthly parallel market exchange rate data computed from the ratio of prices from 1999 to 2008 for Old Mutual insurance company’s shares, which trade in London and Harare. Dynamic semi-elasticities generated from orthogonalized impulse response functions indicate that the monthly seignorage-maximizing rate equaled 108 to 118 percent, generally exceeding monthly inflation.

One often thinks of hyperinflation as showing the weakness of fiat money. But in a strange way it also shows the enormous value of fiat currency. The fact that the revenue maximizing rate of inflation is so high is an indication that people really value their traditional fiat currency, and will only abandon it under the most costly forms of hyperinflation.

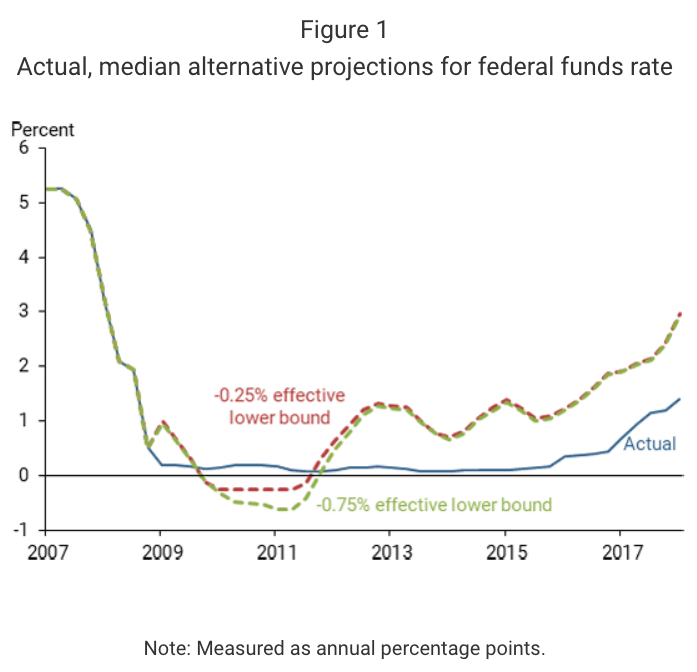

2. It seems like ideas take about 10 years to go from whacky MoneyIllusion posts to conventional wisdom. In early 2009, I said the Fed should consider negative interest on reserves, an idea that was widely dismissed at the time. A new study Vasco Cúrdia of the San Francisco Fed suggests that the actual lower bound was more like minus 0.75% (100 basis points below the Fed target), and that having negative interest rates on reserves would have allowed the Fed to achieve a higher inflation rate and a faster economic recovery.

Some people will complain that they hate the idea of ultra-low interest rates, which punish savers. They overlook another argument I frequently make, which is also widely ignored. A more expansionary policy means higher interest rates over any extended period of time. Take a look at this graph in the Cúrdia paper:

If you want higher interest rates in the future, pray for easier money today.

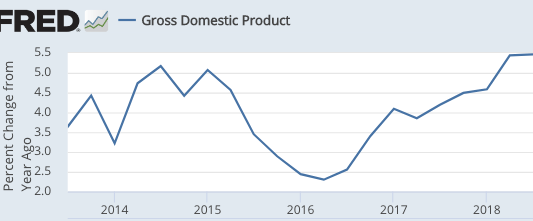

3. In a previous post I discussed a David Beckworth interview with Adam Ozimek, discussing the “hidden recession” of 2016. Now Ozimek and Michael Ferlez have an online paper with a more in depth explanation of what happened. The basic idea is that the Fed raised rates prematurely in late 2015, and this sharply slowed the recovery in 2016.

It is clear from comparing past projections to the current one that the Fed made a numerically significant error in underestimating the amount of labor market slack over the past few years. How consequential this error was depends upon on how the error maps to monetary policy decisions. We utilize two approaches to demonstrate how the Fed might have differed the path of federal funds rates if it had not underestimated labor market slack: a revealed preference approach and a rules-based approach.

This paper provides an excellent case study of why we need the sort of “look back” accountability process that I’ve recently been advocating.

Note: I’m am not saying that 2016 was an actual recession—it wasn’t. Rather it was an unwarranted slowdown in NGDP growth (which may have cost Hillary the election):

HT: David Beckworth

Update: I also recommend this Greg Mankiw review of Trump’s economic policies. I’ve seen Mankiw’s essay mischaracterized as claiming no long run growth effect from the recent tax cuts. That’s not quite accurate, especially under the plausible assumption that the cut in corporate tax rates will be extended beyond 10 years. Mankiw is a moderate supply-sider, as am I.