What I’ve been reading

The Mercatus Center has a new paper by Stephen Matteo Miller and

Thandinkosi Ndhlela, which examines the Zimbabwe hyperinflation. Here is the abstract:

Unlike most hyperinflations, during Zimbabwe’s recent hyperinflation, as in Revolutionary France, the currency ended before the regime. The empirical results here suggest that the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe operated on the correct side of the inflation tax Laffer curve before abandoning the currency. Estimates of the seignorage maximizing rate derive from a short-run structural vector autoregression framework using monthly parallel market exchange rate data computed from the ratio of prices from 1999 to 2008 for Old Mutual insurance company’s shares, which trade in London and Harare. Dynamic semi-elasticities generated from orthogonalized impulse response functions indicate that the monthly seignorage-maximizing rate equaled 108 to 118 percent, generally exceeding monthly inflation.

One often thinks of hyperinflation as showing the weakness of fiat money. But in a strange way it also shows the enormous value of fiat currency. The fact that the revenue maximizing rate of inflation is so high is an indication that people really value their traditional fiat currency, and will only abandon it under the most costly forms of hyperinflation.

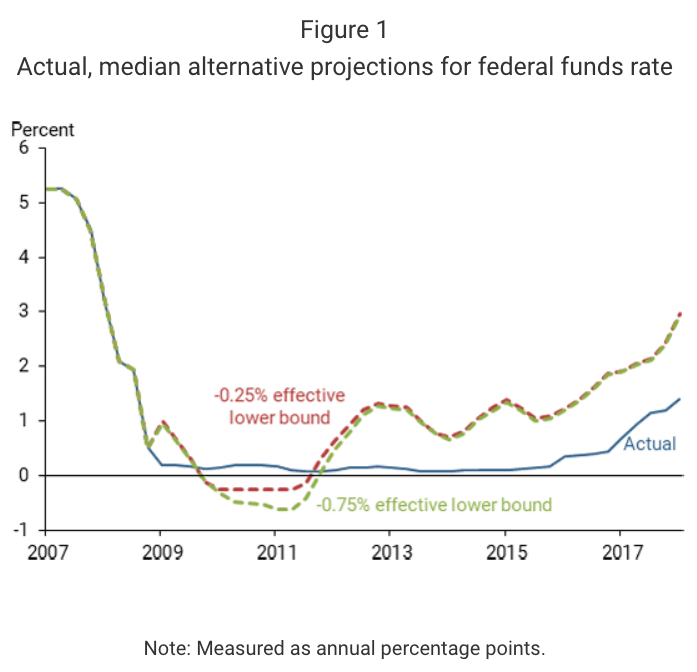

2. It seems like ideas take about 10 years to go from whacky MoneyIllusion posts to conventional wisdom. In early 2009, I said the Fed should consider negative interest on reserves, an idea that was widely dismissed at the time. A new study Vasco Cúrdia of the San Francisco Fed suggests that the actual lower bound was more like minus 0.75% (100 basis points below the Fed target), and that having negative interest rates on reserves would have allowed the Fed to achieve a higher inflation rate and a faster economic recovery.

Some people will complain that they hate the idea of ultra-low interest rates, which punish savers. They overlook another argument I frequently make, which is also widely ignored. A more expansionary policy means higher interest rates over any extended period of time. Take a look at this graph in the Cúrdia paper:

If you want higher interest rates in the future, pray for easier money today.

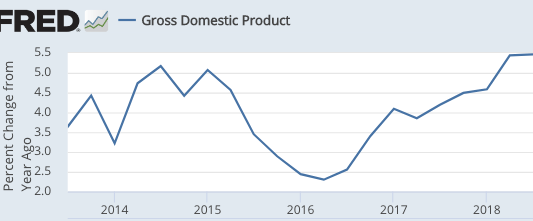

3. In a previous post I discussed a David Beckworth interview with Adam Ozimek, discussing the “hidden recession” of 2016. Now Ozimek and Michael Ferlez have an online paper with a more in depth explanation of what happened. The basic idea is that the Fed raised rates prematurely in late 2015, and this sharply slowed the recovery in 2016.

It is clear from comparing past projections to the current one that the Fed made a numerically significant error in underestimating the amount of labor market slack over the past few years. How consequential this error was depends upon on how the error maps to monetary policy decisions. We utilize two approaches to demonstrate how the Fed might have differed the path of federal funds rates if it had not underestimated labor market slack: a revealed preference approach and a rules-based approach.

This paper provides an excellent case study of why we need the sort of “look back” accountability process that I’ve recently been advocating.

Note: I’m am not saying that 2016 was an actual recession—it wasn’t. Rather it was an unwarranted slowdown in NGDP growth (which may have cost Hillary the election):

HT: David Beckworth

Update: I also recommend this Greg Mankiw review of Trump’s economic policies. I’ve seen Mankiw’s essay mischaracterized as claiming no long run growth effect from the recent tax cuts. That’s not quite accurate, especially under the plausible assumption that the cut in corporate tax rates will be extended beyond 10 years. Mankiw is a moderate supply-sider, as am I.

Tags:

5. February 2019 at 14:40

Thanks for the paper on Zim Hyperinflation. Nice use of a cross currency pairs using Old Mutual Harare traded shares to construct exchange rates.

My only quip, and maybe it was the language in the paper, is the omission of foreign debt denominated in other currencies. Fiat currency gets on shaky ground when you owe debts on foreign currency, and printing your currency to obtain foreign in FX markets can go badly fast.

5. February 2019 at 16:45

Kevin Erdmann posits the Fed may be dancing with another recession presently.

There is a spooky thought. Could the Fed actually reverse its policies, that is lower interest rates and go back to quantitative easing, if that is the proper policy choice at this time?

I don’t think so. Too much inertia.

I wonder also about negative interest rates. The Bank of Japan has deployed negative interest rates on some deposits in Japan. But my understanding is the financial system more or less said will go broke if the Bank of Japan persists with negative interest rates.

Western economies do have this problem; they have an institutional system of commercial banks and other financial lending institutions that, as a practical matter (and particularly in any recession) must be preserved. The endogenous supply of money, and the need for stability in financial markets requires this.

Could the Fed actually impose a -0.75% interest rate on reserves and make it stick? Can commercial banks be compelled to lend into the teeth of a recession?

Well, let us hope we do not see a recession. I wonder if the Federal Reserve has the tools to handle one. It only took us 10 years to dig our way out of the last recession.

6. February 2019 at 01:49

Even Reuters mischaracterizes BoJ policy as “ultra-loose” but that said, you have to like the Japan’s PM and central bankers…..

Japan PM Abe defends BOJ’s policy despite inflation woes

Leika Kihara, Stanley White

3 MIN READ

TOKYO (Reuters) – Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe praised the Bank of Japan’s ultra-loose monetary policy for helping create jobs, suggesting the government wasn’t unduly worried that inflation remains distant from the central bank’s 2 percent target.

Abe told parliament on Wednesday the government “accepts” the explanation given by the BOJ on why inflation has failed to hit its target, stressing the economy would have been in much worse state without the central bank’s stimulus program.

“What’s most important is what is happening to the economy as a result of the BOJ’s target, which is that more jobs were created,” Abe told an opposition lawmaker, who criticized the central bank for failing to drive up inflation.

—30—

6. February 2019 at 04:11

The Fed is confused and confuses, with the result that the economy stays down.

http://ngdp-advisers.com/2018/09/16/yellen-is-confused-confuses/

6. February 2019 at 04:55

I was going to write a thank you for blogging for the last ten years in response to your previous post but this post actually better captures what I want to thank you for: showing me how much of monetary economics is counter-intuitive.

6. February 2019 at 07:14

Figure 1 in the Cúrdia seems inconsistent? I don’t see how a federal funds rate path with an -0.75% effective lower bound results in less stimulus than the same path with an -0.25% effective lower bound. The green curve takes slightly longer to rebound than the red curve, and the subsequent interest rate paths appear identical.

Even if we write that delay off as a visual artifact, it suggests that the marginal effect of -0.5%-0.75% interest rates is near-nil over -0.25%, which then calls into question the description of a -0.75% effective lower bound.

6. February 2019 at 08:54

Matthew, That’s certainly an issue, but perhaps was beyond the scope of the paper.

Marcus, Good catch on that inconsistency.

Thanks Carl.

Majromax, I wondered about that too; maybe someone else can take a close look at the paper and answer this question.

6. February 2019 at 08:58

Scott,

So on point 3) if I’m reading Ozimek and Ferlez correctly, the Fed underestimated real employment. Wasn’t that dummy Trump making that same point two and half years ago.

🙂

6. February 2019 at 09:08

Scott,

On growth, Mankiw said roughly 5% over the 10 year life of the tax cuts. You’re on record saying 2%. Why the difference between you and Mankiw (both moderate supply siders.)

BTW – I think you are both low.

6. February 2019 at 09:16

Scott,

Regarding 2. The ZLB is a myth until I can get a zero percent 100 year fixed rate mortgage. On a risk adjusted basis that translates into a number that’s a lot lower than a negative 0.75% yield on Treasuries.

on The Fed is not limited to buying Treasuries. They can buy assets that actually require economic activity to occur, e.g. new home loans, etc.

Even if we got into a situation where people were actually hoarding crash (decreasing velocity) there are easy fixes beyond negative rates on reserves. The Fed could switch to electronic notes (cash) which could easily carry a negative rate of interest. The Fed could add a surcharge on net cash withdrawals by banks.

6. February 2019 at 09:30

dtoh, You said:

“Wasn’t that dummy Trump making that same point two and half years ago.”

You mean back when he said Fed policy was too easy? Yes, he did.

Just as last night he said he favored an all-time record boost in legal immigration, and just as he said he would pay of the national debt in 8 years, and just as he said the true unemployment rate was as high as 30% or 40% (until the day he was elected), and just as he said he’d take the blame for the shutdown, and just as he said lots of other things. The question is not what Trump says, it’s why anyone pays attention to anything he says.

As for Mankiw, I find it amusing that DeLong claims Mankiw says there will be zero growth effect and you says Mankiw claims a 5% growth effect. It’s like Rashomon, one can find quotes to support any claim. But look at the entire argument he makes—his actual views are almost identical to mine—somewhere between 0% and 5%, with 2% being a good median estimate. He cites lots of low estimates from solid sources, with approval, and then say 5% is the highest plausible estimate. Take another look at the article.

I certainly agree with your liquidity trap argument.

6. February 2019 at 14:22

Scott,

Akutagawa, among other things, wrote two short stories. One was called Rashomon, the other was called Yabu no Naka (In the Bush.) Kurosawa made a movie, out of Yabu no Naka, but Rashomon was a cooler sounding name, so they called the movie Rashomon.

As in Yabu no Naka, there is objective truth and I think that can be discerned in Mankiw’s concluding paragraph of the section of the article on the tax impacts on growth because it is only there where he doesn’t attribute specific growth estimates to a particular economist but instead camouflages his own views with the deliberately vague use of the third person… “one might reasonably argue.”

Of course Mankiw is being deliberately vague because he has job ambitions for when (or if) there ever is a more moderate Republican administration so he’s reluctant to say anything too complimentary of Trump that might later be attributed to him. In this regard he’s no better than Krugman, and it is exactly the sort of behavior that Mankiw is criticizing others for in the article. In words of Akutagawa, a bandit pointing the finger at another bandit.

Which is why the economics is not respected and why economic science progresses so slowly.

6. February 2019 at 14:51

As rates fall, bond prices rise. If you are not getting the benefit of this price rise, then it must be because you have a large fraction of your asset parked in cash. If you feel like ultra-low rates are punishing you as a saver, then clearly the duration of your investments is too short.

I am not sure how the money-market mutual fund world would deal with negative rates. As it was with 0.25% rates, most had to waive their fees to keep from “breaking the buck.” The conventional wisdom is that if you do break the buck that means the death of your fund.

6. February 2019 at 17:15

dtoh, Yeah, I’ve read both stories, but I figure people would be more likely to get the movie reference.

As for Mankiw, it’s clear his from his earlier blog posts that he despises Trump and he is pretty dismissive of the extreme supply-siders who support him. The entire point of his FA article was to criticize the claims of Moore and Laffer. So no, I doubt he necessarily believes the high end estimates. If he did so, why say that all sorts of respectable economists have lower estimates?

I think that rather that cast doubt on Mankiw’s ethics, it makes more sense to take him at his word—that most respectable growth estimates are quite low, with 5% being the highest plausible estimate. That’s what he said, and I have no reason to doubt that’s what he believes. It’s also what I believe.

6. February 2019 at 22:16

Scott,

You’ve clearly stated your estimate of growth and the reasons for it. So the fault is in your logic not your integrity. 🙂

The same can not be said of Mankiw who has a two decade history of hedging his views to please his political masters.

BTW – Did you know a lot of Japanese used to call George W. “Yabu?”

7. February 2019 at 03:33

Fed Turning to Negative Rates Would ‘Blow Up’ Money Markets, Boockvar Warns

By Alex Harris

February 7, 2019,

In a letter published Feb. 4 by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, researcher Vasco Curdia argued that had policy makers cut rates below zero following the financial crisis, they could have “mitigated the depth of the recession and sped up the recovery.” Yet Peter Boockvar at Bleakley Financial Group is among those pushing back, warning that the adoption of a negative interest-rate policy by the central bank would have dire consequences for markets.

Tax on Capital

“NIRP in the U.S. would blow up the money-market industry, the source of $3 trillion of funding for a variety of short-term debt,” wrote Boockvar, the firm’s chief investment officer, in a Feb. 5 note to clients. “How exactly would a tax on capital lead to faster growth?”

—30—

7. February 2019 at 06:52

Scott, that the revenue maximising inflation rate is so high shows the power of status quo, Schelling points and network effects. Not sure it says anything about fiat vs other types of currency?

Benjamin, how would negative interest on (excess) reserves tax capital?

7. February 2019 at 09:53

dtoh, I’m not going to criticize Mankiw for being more diplomatic than me. And he’s been very critical of Trump, who is “master” of the Republican Party.

Ben, The whole point of negative IOR is to “blow up” (i.e. reduce demand for) money.

Since when did money become “capital”?

Matthias, Agree it is network effects; my point is that even a badly run fiat system has real value to society. I think we agree.

7. February 2019 at 15:25

Bah, the paper with the framework for the graph is gated.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0304393214001457

A strange thing in the SNB balance sheet is that the SNB has 4 billion CHF of “Swiss Franc securities” on their balance sheet. 190 billion CHF in government debt exists for Switzerland. The vast majority of the SNB’s balance sheet is 763 billion CHF in foreign currency reserves.

Why has the SNB done -0.75% negative rates and done so little QE?

7. February 2019 at 20:08

Why do you consider yourself a supply Sider? Weren’t you one of the few conservatives who thought the recession was demand side?

7. February 2019 at 20:33

Benny, I think Scott is a supply sider in the sense that once you have a decent monetary policy, like nGDP level targeting, there’s nothing else to do on the demand side. No deficit spending etc.

The rest of economic policy Scott finds important is all the stuff your econ 101 text books tells you: lower barriers to entry, free trade, simple taxes, avoiding deadweight losses, etc. All mostly standard fare amongst economists and technocrats.

Scott, please correct me, if I’m wrong.

8. February 2019 at 04:53

Scott and Matthew:

I am not endorsing Peter Boockvar at Bleakley Financial Group.

It is how some people in the financial industry look at negative interest rates. There may be some truth in his commentary—yes, negative interest rates are a type of tax if collected by a federal agency (in this case the Fed, and not the IRS). Maybe money-market funds will dry up. You could get a “run” on money-market funds. What would be the consequences of that?

Personally, I feel some uneasiness at negative interest rates. Feels like we are exploiting the fact that Americans cannot safeguard ordinary paper cash.

Obviously, rather than accept negative interest, most people would convert to cash, if cash was completely safe. There is convenience to digital cash (online purchases, automatic payments, transferring money long distances, etc.). However, there are services that will take your cash and send digital, such as Western Union.

Interestingly cash in circulation in Japan is the highest in the world. Even in the US, cash in circ is at more than $5k per resident. Yes, $%k and growing!

I sometimes wonder if the Japan economy is doing better than known, due to cash in circ. Small businesses and services in Japan take cash.

If the Fed stays with negative interest rates long enough, we will see a bifurcated economy, one above-ground and digital and taxed and probably stagnant, and an untaxed below-ground cash economy, growing rapidly. We see some of this already with low interest rates.

Maybe this will be “fair.” Blue-collar types can often offer services for cash. Tougher to collect cash as a white-collar employee.

The very wealthy appear to know how to transfer cash without detection.

8. February 2019 at 12:43

Switzerland had weak NGDP growth (in CHF) until recently. NGDP was still <1% for two years after the -0.75% rates were implemented. Deeper negative rates with restrictions on cash printing may have been necessary.

At a deep ZLB, concrete tools include:

1. Netative IOR with restrictions on cash printing.

2. QE of private assets.

3. Money-financed tax cut (helicopter money)

I used to support #1, but I worry more now about real-world disruption. #2 is probably the easiest politically but has awful ramifications.

So I support a money-financed tax cut. Say, the Fed could say "we are increase money by $500 billion." Anybody can tender their Treasuries at 0% rates. The shortest durations tendered get bought first. If not enough Treasuries are tendered, then it falls back on a tax cut.

8. February 2019 at 14:35

Benny, See Matthias’s comment. I’m a bit more supply side than the average economist, because I think the median economist underestimates the incentive effects of taxes.

But yes, 2008-09 was demand side.

Ben, I feel uneasy about both QE and negative rates, and also open heart surgery and chemo. Better to avoid getting sick in the first place.

Matthew, The Swiss minus 0.75% was adopted as part of a contractionary (NeoFisherian) policy. If we use negative IOR, it should be part of an expansionary policy, not contractionary.

8. February 2019 at 15:24

Although to break out of the NeoFisherian trap, SNB may need one of the three unorthodox tools. Or the true threat to use one of the three tools.

The currency peg was essentially QE of private assets. At least it put faith in the ECB to retain the Euro’s value, even though the Swiss have no control of the ECB.

8. February 2019 at 21:27

@Benjamin Cole

Good point on Japan, I would note…

1) This is already happening in Japan, which is why Japan has by far the best restaurants and manicurists in the world.

2) The trend has nothing to do with monetary policy, it is entirely driven by a confiscatory tax policy.

3) The downside is that it tends to concentrate economic activity in industries which are not capital intensive, which leads to low investment, which in turns leads to low economic growth, which leads to population decline.

4) If you’re already affluent and a foodie, it’s nirvana. For everybody else, you’re totally screwed.

8. February 2019 at 21:54

@Scott,

I think it’s important to emphasize that expansionary monetary policy works by inducing the non-banking sector to exchange financial assets for goods and services (I know you have slightly different view of the transmission mechanism.)

This happens in two ways, either by raising the price of financial assets (i.e. lowering rates or the cost of borrowing) or by raising the expected return on good and services (i.e. expected of NGDP growth.) Normally the second (raising NGDP expectations) dominates the first (lowering rates,) which is why one sees rising rates during an economic expansion.

Bottom line if the Fed were credible (which they are not because they’re incredibly incompetent,) the market would never expect negative NGDP growth, and the ZLB would never be an issue except as an interesting blog topic.

9. February 2019 at 09:35

Matthew, At a minimum, they shouldn’t have revalued the SF against the euro. All they had to do was keep the exchange rate peg.

dtoh, Yup, have a good policy and you don’t need negative IOR.