How many punches should Chuck Norris be allowed to throw?

A number of market monetarist bloggers use the “Chuck Norris” metaphor for monetary policy credibility. The basic idea is that if the central bank credibly promises to do whatever it takes to hit its target, then NGDP growth expectations won’t fall very far, nominal interest rates will stay above zero, and the central bank won’t have to actually take many “concrete steppes” to hit its target. Exhibit A is the Reserve Bank of Australia, which never had to cut rates to zero or do QE during the global recession of 2008-09. And yet the Aussie outcome was better than in other advanced economies. The Chuck Norris metaphor refers to the fact that he can clear a room without throwing a punch, just due to his reputation.

Chuck Norris is a good metaphor, but (as far as I know) other bloggers have not fully fleshed out this line of reasoning. The focus has been on what central banks need to do, but perhaps the real focus should be on what governments need to authorize.

Consider two countries with central bank balance sheets equal to 5% of GDP, both on the eve of the Great Recession. In each case, the balance sheet balloons to 25% of GDP during the Great Recession. In which case is policy more expansionary?

Case A: The central bank is legally limited to a balance sheet of no more than 25% of GDP.

Case B: There is no legal limit on the central bank balance sheet.

In case B, the expansionary impact of the QE will probably be much greater than in case A. While the “concrete steppes” are identical, in case B there will probably be expectations of a more expansionary future policy than in case A. Nick Rowe often points out that the current concrete steps taken by central banks are far less important than changes in the future path of policy. That’s implicit in the Chuck Norris metaphor, and also an implication of state-of-the-art New Keynesian models developed by Michael Woodford and others.

At this point you might assume that the implication of my post is clear—don’t have legal limits on central bank balance sheets. But a decade of reading deep thinkers like Tyler Cowen and Robin Hanson (or petty much any of the George Mason bloggers) has convinced me that when it comes to human institutions, things are always more complicated than they seem, certainly more complicated than they seemed to me a decade ago. For instance, let’s add another case:

Case C: The central bank’s balance sheet is legally limited to 250% of GDP.

Now let’s think about Fed policy during the recovery from the Great Recession. We know that the Fed did three QE programs, and stopped when its balance sheet was just under 25% of GDP. We know that Bernanke cited vague “costs and risks” of doing even more QE. (Although we also now know from the FOMC transcripts that Bernanke himself was less concerned about these risks than other members of the committee.) And we know that some in Congress were complaining about all the money printing, and almost no one on Congress were complaining that they did not print enough money.

To summarize, while the Fed was in Case B, with no legal limit on their balance sheet, the institution behaved as if there was a sort of implicit limit, probably much lower than 250% of GDP. In that case, moving to case C might have actually been expansionary. The Fed would have thought, “Congress has our back, they authorize us to do truly massive QE if necessary to achieve our mandate.” Think of Russian highway speed limits changing from “no explicit limit but at the discretion of what the police officer views as unsafe” to “150 kilometers per hour”. Do speeds rise or fall?

In a perfect world, I’d want Congress to tell Chuck Norris that he’s authorized to throw as many punches as required to clear the room. Or perhaps to authorize a specific number that is clearly more than he would need (say 10,000 punches.) But I’m not sure about the idea of actually having Congress set a limit. If they had done so back in 2008, the limit on the central bank balance sheet would likely have been set too low.

Because Congress is so dysfunctional, and likely to remain so, one could argue that the Fed can pretty much do whatever they want. Who will stop them? The Fed is about 100 times more respected than Congress, and any Congressional attempt to control the Fed would almost certainly fail to get 51 votes in the Senate (which actually has a few grown-ups). There are plenty of pragmatic GOP senators (say among people like Lindsey, McCain, Flake, Collins, etc.), some of which would not support a right wing attempt to rein in the Fed. Heck I doubt even Trump would support it, as he knows he might need monetary stimulus if we again go into a recession. So perhaps the Fed could simply put on its Superman costume (sorry for mixing metaphors) and unilaterally announce that it views itself as being authorized to lower IOR to as much as negative 0.75%, and boost the balance sheet to as much as 250% of GDP, and then dare Congress to stop them.

That won’t happen (Larry Summers was not picked to be chair), but it’s the sort of issue we should be thinking about. Instead we think about question like “does QE work?” Which is such a dumb question it makes my hair hurt every time someone asks it.

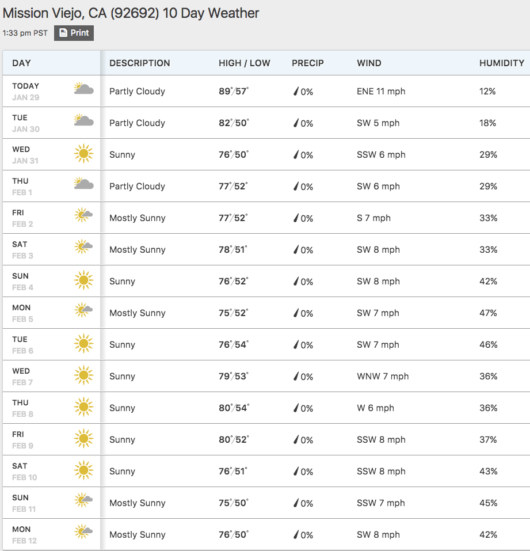

Update: People keep asking me how I enjoy California:

Tags:

29. January 2018 at 13:40

You’re assuming that only GOP senators would mount a foolhardy mission to wipe out Fed independence. Experience suggests stupid ideas tend to be somewhat bipartisan. If Sanders and a couple populist Democrats join the Tea party revolt against the Fed they might have enough power to actually restrain its abilities during a time of crisis. The Fed is caught in a strange paradox where any attempt to fix the problem might lead to idiots removing its tools to fix the problem. I don’t envy the politics associated with being head central banker.

29. January 2018 at 13:49

John, You said:

“If Sanders and a couple populist Democrats join the Tea party revolt ”

Yeah, let me know when that happens. Seriously, I don’t doubt that the Dems have some whacky views, but they are most certainly not the same whacky views as the Tea Party.

29. January 2018 at 14:55

Re: CA. You were lucky you weren’t affected by the Thomas Fire or the mudslides afterwards. I wasn’t directly affected either, but I took in refugees from Ojai (from the fire) for a week and was cut off from using the 101 to go South (making what should have been an easy 1 hour drive a harrowing 5 hour drive, including route 166) because of the two week long mudslide closure.

But yes, today I noticed my neighbor’s fruit tree was full of blooms! Spring has arrived! Lol

29. January 2018 at 15:07

To echo John’s sentiment, I do believe it was one of my lefty friends who recommended “The Creature from Jeckyll Island,” and spent the better part of an hour trying to explain how reserve requirements allow banks to create money.

‘Something something “illuminati,” something something “freemasons,” etc. etc.’ You get the idea.

29. January 2018 at 15:33

@Randomize, I first heard about “The Creature from Jeckyll Island” from my conspiracy theory loving, Alex Jones watching neighbor. Politically I’d have to call him more right than left as Jones has gone in full #Cult45 mode (and thus my neighbor too). But a weird mix of right and left lunacy nonetheless. I never talk to him more than 5 minutes for fear the conversation will turn to the evils of The Fed, chemtrails or how many people the Clinton’s, Bush’s and William Mulholland have personally murdered. Otherwise, he’s a nice enough guy.

29. January 2018 at 15:40

Randomize, Yes, but once again, that has nothing to do with the Senate.

29. January 2018 at 16:33

Excellent blogging.

I live in humid heat. Man, SoCal is nice.

29. January 2018 at 16:51

If the Fed is going to unilaterally announce that it views itself as being authorised to do something, then why not just say “whatever it takes” as Draghi did (even when it wasn’t true)? It sure worked and it might be less controversial to pick a straw man and say you’ll do anything to avoid another Great Depression than talking precise numbers like 250% of GDP.

Re Orange County living, those temperatures seem way higher than long-term averages; even given some global warming.. Also, I’ve heard about large homeless slums in Orange County, or is that not near where you live?

29. January 2018 at 17:23

-HAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAHAH.

Neither of these two are worth a damn. Caplan’s worth a lot. You’re worth a lot. Even Noah Smith, heck, even Matt Yglesias, is worth a little. I have seen nothing insightful come out of the keyboards of either Cowen or Hanson.

It’s a simple question. The answer is “yes”.

29. January 2018 at 19:40

I think John is on to something, though I don’t quite agree that he would outright join the Tea Party, even if he’d get onboard with something like “audit the Fed.” (To be honest, that probably wouldn’t change all that much, though it could have a similar, albeit more pronounced negative impact on the extent of discourse at FOMC meetings than releasing transcripts with a 5-year lag. I believe there’s some research on this.)

Anyway, Sanders wrote an op-ed back in 2015 attacking the Fed for hiking. See here: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/23/opinion/bernie-sanders-to-rein-in-wall-street-fix-the-fed.html ; I can’t recall whether you wrote about this at the time.) Looking aside all of his ‘populist’ rhetoric, the scariest line in his piece might be:

“As a rule, the Fed should not raise interest rates until unemployment is lower than 4 percent. Raising rates must be done only as a last resort — not to fight phantom inflation.”

Now, I suppose someone might want to store this in the Evans Rule 2.0 category (or 3.0 since he already included 2.0 in a speech; ironically, I wrote my own Evans Rule 2.0 before that speech was published), though I think it’s far different when a politician is trying to impose his will on the Fed. Now, it’s perhaps somewhat less controversial that the natural rate of unemployment is somewhere in the 4’s, if not lower a la Japan. At the time, I think it was considerably more controversial, and I highly doubt Bernie and his cohort of economic advisors–MMT’ers and people who think you can ride AD stimulus to a decade of 5 percent growth–know better than Yellen and Fischer where the natural rate is (provided of course we’re in such a regime where that’s what the Fed cares about, rather than NGDP).

I guess what I’m getting at is, though I often think slippery slope fallacies go too far, it does concern me that Congress could be crossing a line in such a case as to specify a cap for the ratio of assets on the balance sheet to GDP (one that is probably extremely arbitrary to start with) such that moves, like Sander’s, would be seen as commonplace — and then we’re battling back and forth between people like Sanders who want the Fed to almost never tighten monetary policy and people like Rand Paul (and his friend, Peter Schiff, whom I know you know well; that was my all-time favorite CNBC segment, by the way) who want a gold standard.

Now, to your point on the extent to which it would be expansionary, I think there also is a plausible objection to that. Let’s say for the sake of argument the Fed didn’t set a cap for itself, but indicated that a balance sheet of size X% would be sufficient to stabilize NGDP, but they’re willing to go further if need be. Let’s assume, for the sake of argument, X is lower than whatever arbitrary figure Congress would come up with. Setting a cap directly might cause market participants to tamper down their NGDP expectations, though as you’ve noted here, the concrete step of outright asset purchases is rather meaningless relative to the comment to do whatever it takes. A larger balance sheet would probably be consistent with slow NGDP growth and thus tight money in the same way as persistently low interest rates, so a direct commitment of this kind could actually boost NGDP expectations substantially such that they stabilize around, say, 4 percent or whatever target level is embedded in the Fed’s mandate. While I do think a willingness to go to some crazy number like 250 could also boost NGDP expectations, it does beg the question in a few respects: (a) would the Fed go that far? (probably not; they’d likely worry about inflation expectations on the upside); (b) it would probably be implemented gradually, so why would monetary policy be so tight for so long as to merit the rolling out of even more QE?; and (c) would Congress take other steps, particularly in the future, to try to restrain monetary policy (in which case Treasury yields and expected monetary policy may end up far more reactive to elections)? I also think another issue might be, especially if the long-run balance sheet size is presently indeterminate, whether the Fed could conceivably run out of available assets purchasable by its mandate, which almost surely would dampen its ability to commit to doing ‘whatever it takes.’

29. January 2018 at 22:17

Aside: If a central bank has resort to money-financed fiscal programs in its tool-kit (aka helicopter drops), the market might pay closer attention central bank posturing.

In fact, what if a central bank known first resort was to helicopter drops?

That’s called “Chuck Norris wearing brass knuckles.”

30. January 2018 at 01:01

Comparing 2008 Fed to 2008 Australia is like comparing 2008 Fed to 2006 Fed. The 2006 Fed simply did much better because the natural rate didn’t go below zero and there was not a systemic banking crisis. The Fed had pretty much the same exact people in 2006 and 2008.

Neither did the bank of Australia have a wide ideological divergence. As far as I know, they never did any remarkable MM/NGDPLT signalling to say their balance sheet or tools were unbound. They simply weren’t tested, like 2006 Fed wasn’t.

Thee anti-concrete-step argument is sort of impenatrable, because it assume literally unbounded concrete steps would be on the table. If there was a helicopter money concrete steps, like Bernanke’s paper, then certainly the central bank could create whatever NGDP growth path it wanted.

Bernanke’s paper didn’t use “helicopter money” in an abstract sense though. The paper really was about a specific concrete steps. The BOJ would supply unlimited money to the Treasury, WITH the Treasury/tax authority rebating the money directly. If that was on the table in 2008, then of course that would have worked. Ideally, the Fed would have traded out the helicopter money concrete steps for the concrete steps it did use:

1. Bear Stearns and AIG bailouts

2. Expansion of collateral for discount window

3. Expansion of discount window to tri-party repo with PDCF.

4. Unlimited insurance of Money Market funds

5. OMO’s of Agency MBS

6. TARP, which wasn’t Fed but was a concrete steps that happened

As much as these concrete steps probably may have helped NGDP, I have some real qualms for how they hurt RGDP. They are big distortions, giving a long-term backing to big bank debt.

I have real qualms with other concrete steps possibly added as well. OMO’s of equities or private bonds puts Fed in direct position to vote in proxies or bankruptcies. Private debt has many decisions: do you enforce your loan covenants? Do you renegotiate debt outside of bankruptcy?

The concerns have been waved off before with expectations. If the Fed would, in theory, buy trillions of assets in a week, then it won’t have to. As I’ve learned more about market microstructures, I’ve become more unconvinced. It would need real people at the New York Fed and 19 primary dealers to really find trillions of dollars in assets.

As actually following through on concrete steps becomes more unlikey, the more likely the market would force the Fed to follow through. The real-world issues would feed back to an efficient market testing the Fed.

In addition, there is possibility of inefficient and irrational markets. 2008 gave large profits to arbitrage trades when pricing should have been “arbitrage-free.” The real-world demand for withdrawals was simply too strong. Even if traders saw arbitrage profits plainly, their investors ultimately control their funding. In this case, the irrational actors would augment the rational actors possibly testing the Fed’s concrete steps.

So, in conclusion, I think it’s really important to think about concrete steps now. A computer doing monetary policy, as Friedman envisioned, would be ideal. Especially if the discount window or primary dealers OMO system could be eliminated. But the exact concrete steps should be hammered down before they’re needed. The computer needs to be figured out in good times.

30. January 2018 at 08:09

Bernanke’s biography illustrates how Paul and Sanders had more or less the same views on what to do to the Fed (ie nuke it). The only difference was Paul was much politer while proselytizing his nuttery.

My point is that central bankers don’t get paid nearly enough money to rock the boat without a clean consensus. 10 senators yelling at the Fed committee in front of a congressional subcommittee is probably enough to deter them from massively expanding the balance sheet. Are central bankers really that afraid of having their feelings hurt by congress? It’s possible: for example FDA bureaucrats are well known to be highly risk-averse in approving drugs even though regulators are rarely fired for accidentally approving a drug proven to be dangerous later. The only deterrent is less prestige and a dressing down on CSPAN at 11 AM, yet this deterrent seems to be pretty effective at making sure the FDA slows drug approvals down to a crawl.

30. January 2018 at 08:19

Fred, None of the comments I’m seeing from you or others in any way contradicts my claim that Congress is too gridlocked to pass laws controlling the Fed.

Saying that Sanders is a loony dove actually supports my claim.

I don’t understand your final paragraph.

Harding, I’m not surprised that they are way over your head.

Matthew, You said:

“The concerns have been waved off before with expectations.”

I’m not sure you actually understand the role of expectations. They are not a minor factor to be added to concrete steps. Expectations are 99% of monetary policy.

As for the Fed buying stocks, I agree that’s undesirable, which is why I favor NGDPLT.

However, although we both agree that it’s undesirable for the Fed to buy stocks, it’s far, far, far, far more undesirable for the Fed to miss it’s target.

1. Best policy. A good policy regime, where the Fed doesn’t buy stocks.

2. Second best: A bad regime, where the Fed buys stocks.

3. Third best: The Great Depression.

30. January 2018 at 08:22

John, You said:

“10 senators yelling at the Fed committee in front of a congressional subcommittee is probably enough to deter them from massively expanding the balance sheet.”

So you agree with me? That’s what I said in the post:

“We know that Bernanke cited vague “costs and risks” of doing even more QE. (Although we also now know from the FOMC transcripts that Bernanke himself was less concerned about these risks than other members of the committee.) And we know that some in Congress were complaining about all the money printing, and almost no one on Congress were complaining that they did not print enough money.

To summarize, while the Fed was in Case B, with no legal limit on their balance sheet, the institution behaved as if there was a sort of implicit limit, probably much lower than 250% of GDP. “

30. January 2018 at 09:52

You gotta love the weather out here. It’s too bad it allows the politicians out here to get away with a whole lot of crazy without chasing everyone away.

31. January 2018 at 06:38

The tone of my post sounded like I was devaluing expectations compared to concrete steps. But really expectations and concrete steps are intertwined. NGDPLT/Expectations are not orthogonal to each other but two sides of the same count. NGDPLT/Expectations, even under perfect EMH, depends on the concrete steps the Fed could honestly threaten.

The real world is also far from perfect EMH. A systemic banking crisis without a discount window or de facto deposit insurance is not going to have super-rational, long-term behavior. I say de facto deposit insurance as the US government backed money market bonds and essentially backed all TBTF bank liabilities.

31. January 2018 at 08:11

I’m a little lost here Scott….

Chuck Norris works without even thinking about 25% of GDP and Congress.

Fed sets NGDP at 4.5% and on the timeline

Mar ’18 GDP is gong to be $19.26T it is predicted to be $19.39T, so fed raised rates in Feb.

Still not enough, Apr ’18 it was meant to be $19.41, it is predicted at $19.47, Fed raises again. HARDER.

And the market slows down.

THAT is effect of Chuck Norris. Because, years ago, when we adopted NGDPLT, the market didn’t think Fed would give up discretion, but they DID, and for the first few months, market tried to race the Fed and JESUS THAT FOURTH RAISE WAS BRUTAL. Don’t go there again.

Thats it.

Yes, I know it’s slightly more complicated bc they rejigger numbers, but it is the adherence to NGDPLT that knocks the market for the loop ONCE< and they get in line.

Why are you talking about giving Fed more discretion?

What am I missing

31. January 2018 at 11:20

My apologies if my earlier comment wasn’t clear. I think the last paragraph is probably the most interesting, so I’ll elaborate a bit more on that. I think you might be right that congressional gridlock could prevent significant, anti-Fed legislation, though I do worry that the Sanders/Warren types, under the veneer of populism not much unlike Trump, might support some of this legislation for different reasons: Republicans because they oppose ‘easy money’ (perhaps less so soon with a Republican nominee leading the Fed) and Democrats because they view LSAP’s as “bank welfare” or something of that kind.

Anyway, my last paragraph could have been worded far better, so here’s what I was trying to get at. You’ve commented in the past, and in this post by referencing Australia, that ‘concrete’ steps are far less relevant than the perception amongst market perceptions as to the Fed’s willingness to do ‘whatever it takes’ to achieve its mandate, however we might define that. In that sense, the size of the balance sheet probably doesn’t mean all that much, because QE of size X/Y% would be less effective than QE of (X-n)/Y% for some arbitrary n if the former, but not the latter, were paired with such a commitment.

Drawing on this, the cap might not have all that much effect if the Fed, as is likely, hadn’t any willingness to actually hit such a number, nor viewed it as necessary to hit its mandates in a timely manner. But, let’s say for the sake of argument that Congress set such a cap and the Fed–as will almost surely happen–was unrelenting in terms of voicing its opposition as it would ‘curtail its ability to respond to economic crises.’ (The only point of agreement I made here is that the balance sheet will likely remain quite large even after the Fed finishes its current drawdown of reinvestment, so that erodes its future ability to promise to do ‘whatever it takes.’ Because the promise that it could do more if needed is far more important than actually doing it as it relates to keeping NGDP expectations, and thus actual NGDP, stable, this could pose a significant problem.) Market participants might respond: “Well, if such a large, future concrete step were required, clearly even the Fed believes that it’s current toolkit and its current policy mix is insufficient to achieve its target. I’m lowering my NGDP expectations.” That, of course, could be self-reinforcing.

Hopefully that was a bit clearer and sounds somewhat plausible.

31. January 2018 at 14:29

Morgan, I was not talking about giving the Fed more discretion. And I was assuming the economy was at the zero bound, where rate changes are not an option.

Fred, I think we agree, if you are saying that a cap might reduct NGDP expectations.

31. January 2018 at 14:36

You’re forgetting what actually happened. The Fed got permission to pay interest on both required and actual reserves precisely because they did NOT want to stimulate the nominal economy while they engaged in credit allocation. They said that the credit allocation they engaged in was supposed to save the economy, but the IOR policy was specifically designed to sterilize the balance sheet expansion.

What they were doing was trying to save individual members of the financial community rather than the national economy. We should never forget that the recession and slow recovery afterward is entirely the Fed’s fault.

31. January 2018 at 14:38

Excess reserves, not actual reserves.

31. January 2018 at 15:10

I think that’s fair, though I think it might go somewhat further than that. I’ve always been quite perplexed, especially recently, when people argue for fiscal stimulus. (Sanders is getting his due mention in this comment section for sure — him and his ’emergency jobs program.’) The crux of the opposition to that is, I believe, not quite Ricardian equivalence or budget deficits; the latter is surely a concern, the former much more questionable. Rather, it’s your signature term, monetary offset, which hinges on the fact that monetary policy CANNOT run out of ammunition unless, somehow, the Fed ran out of assets on the planet to purchase–or, perhaps, within its legal purview. With a cap, however, the Fed may in fact run out of ammunition. ‘Whatever it takes to achieve our mandate’ would become ‘whatever it takes until we exceed our Congressional mandate cap that may well clash with our mandate.’

Then, the case for fiscal stimulus and socialist policies–I believe you authored a paper raising this–gains traction, and you have people who believe low rates mean easy money, emboldened by their prior cumbersome measure on the Fed and now convinced the Fed is clearly too incompetent to handle it on its own (kind of like Trump gutting the ACA by executive fiat or via repealing a key component of the three-legged stool in his tax bill, only to point how much the law subsequent fails) trying to pass additional laws shackling monetary policy. It’s not quite a slippery slope, but I think a clear logical progression into Congress running monetary policy.

1. February 2018 at 18:03

Chuck Norris should throw as many punches at this blog as he can

https://i.imgur.com/n6V9L07.jpg

5.4% biotch

Remember “Trump is a moron, Trump is a fool”?

This moron and fool’s policies just got real GDP growth to grow OVER 5%

1. February 2018 at 19:08

Q_Anon: There are several problems with this.

(a) That is the Atlanta Fed’s GDP tracker, NOT the BEA’s estimate (not even its advanced estimate). The GDP tracker is known to be highly volatile from day-to-day. Not to mention, we’re only a third of the way through the quarter. Watch that number move.

(b) Exports were a substantial factor bolstering GDP forecasts. Professor Sumner wrote a post a while back explaining that the Trump administration is deceptively changing the measurement of exports so that it ‘appears’ that RGDP is higher when in fact not much has changed at all.

See here: http://www.themoneyillusion.com/?p=32753. He cites a great post by Noah Smith on this subject.

(c) Even if that held, and even if I gave Trump credit for it, I highly doubt you’d be willing to apply the same standard to Trump when you see a quarter-to-quarter fluctuation that doesn’t support your argument. The same is true when Trump (asymmetrically) takes credit for stock prices.

(d) I don’t think Trump had any impact whatsoever on that. I think EVEN IF that is the number, it’s a lagged effect of monetary policy over the past several years. The only thing Trump himself actually did–aside from take credit for employment numbers immediately upon taking office due to the ‘confidence fairy’ that he previously insisted were fabricated–was deregulate and just recently pass a tax cut. The effects of the tax cut are long-term in nature, so even if you’re reasonably bullish on them, as Professor Sumner is to an extent (I’m not, but I often say that on the 5 or so percent of things on which I disagree with him, he’s probably right), it’s unlikely they had much effect on the Q1 number. Deregulations might have said effect, but perhaps a few tenths in RGDP. The overwhelming cause is monetary policy.

2. February 2018 at 05:38

Scott,

“Morgan, I was not talking about giving the Fed more discretion. And I was assuming the economy was at the zero bound, where rate changes are not an option.”

NGDPLT takes away Fed discretion. Right?

In your 3 cases, I thought you were giving Fed discretion.

I simply meant if we have NGDPLT, the fed could do these 3 things.

Fred,

That’s some Koolaid you are drinking. Yes, it’ll be restated, but you are simply nuts to be asserting this isn’t Trump…. the tax cuts are nice and all…

BUT the real Trump effect, is simply the YESs going on everywhere. Every port dredging project, every everything that was sitting covered in tape and Obama USG bureaucracy has been greenlit AND

Everyone knows the getting is good.

I hear it everyday talking to everyone who owns operates a business. Approvals? BAM.

Trump’s got an infrastructure plan that basically makes PRIVATE INFRASTRUCTURE never pay taxes on their profits.

So Flint Water & Sewer will be privatized (just like in Texas).

And again, the spending side isn’t going to be the BAM.

The BAM is going to be everything getting approved in one year, bc states that reduce the aproval time get $$$ and DC will never say anything but YES.

2. February 2018 at 10:35

Fred,

The infrastructure plan to me seems like nothing more than crony ‘capitalism.’ I wasn’t aware the corporations owning the infrastructure would be exempt from paying taxes. That strengthens my point. (And I’m not saying that because I’m hungry for their tax money. I support a lower, consumption-based tax system, but under this system, it’s very difficult to justify such a disparity, especially for well-connected corporations.)

The spending side by definition can’t be the ‘BAM’ — it’ll be offset by tighter monetary policy. That is, unless it boosts productivity. Call me skeptical that a president who has bankrupted his businesses–including his casinos, for goodness’ sake– so many times would make the correct investments capable of generating a decent return.

In my last post, I said that deregulation could boost RGDP. I just don’t think it’ll have much effect — certainly not even close to 5.4%, which is the number the other poster cherrypicked from a single forecast when we’re only a third of the way through the quarter. (In other words, if that forecast were cut in half by next week or stocks fell by X percent, you would never these posters return to attribute it to Trump.) I’m at least consistent on this point, which is that nominal stability is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. We can change the composition of that somewhat with decent supply-side policy, but tinkering-on-the-edges tax reform, most of which is set to sunset down the road, and even higher budget deficits will hardly achieve that. Not to mention, these effects are long-term in nature.

The ‘BAM’, as you’ve defined it, is beside the point. We’re talking about a Q1 GDP forecast, and you’re talking about things he will do at some future date. The two are completely unrelated.

2. February 2018 at 10:35

Oops, I meant to address that post to Morgan. I wish there were some way to edit these comments…

4. February 2018 at 11:01

Fred, You said:

“Then, the case for fiscal stimulus and socialist policies–I believe you authored a paper raising this–gains traction,”

Not really, Why would a Congress that prevents the Fed from adopting monetary stimulus itself adopt fiscal stimulus? Much of the opposition to monetary stimulus comes from the GOP, but they are equally opposed to fiscal stimulus.

Morgan, Those three cases are not talking about discretion, they are discussing how much power the Fed has. How they use that power is an entirely different question.

18. March 2018 at 04:19

Don’t you worry that buying “risky” assets (compared to government bonds) could generate losses when the time comes to raise rates aggressively to stop inflation?

What if this affects central bank independence when, in the case of a really negative balance sheet, the government has to step in by providing free bonds to the Fed or money to cover the losses?

Could monetary policy be compromised?

19. March 2018 at 12:41

Inklet, Yes, of course I worry. That’s why I favor NGDPLT at 4%, so the Fed won’t have to buy risky assets.

But if they don’t have a sound monetary regime, buying risky assets is 100 times less bad than alternatives, like 10% unemployment or fiscal stimulus.