Where does all the time go?

I just noticed that I’ve fallen behind on the set of podcasts by David Beckworth, so I will work through the ones I’ve missed, starting with the Greg Ip, one of our best economic journalists. Here’s my favorite comment by Ip:

And it actually may be better to have lots of small financial disruptions than one big financial disruption.

In Greg’s recent book he discusses this idea in more detail. In the interview, Greg uses analogies such as the danger of continually preventing small forest fires, and thus building up fuel for a catastrophic fire.

Over the past 50 years the government has prevented financial crises about every decade or so, by either bailing out depositors of large banks, or arranging assistance in the case of LTFC (1998). And this had the effect of storing up fuel (moral hazard) for an even bigger crisis in 2008. But I would go much further that Ip, who approves of FDIC. It’s not politically possible to abolish FDIC, but perhaps we could create a two-tier system where insured deposits are backed by safe assets, so that taxpayers are not put at risk. Deposits used for lending to businesses and homebuyers would not be insured, but would offer higher interest rates to depositors. Let bank depositors choose how much risk they are willing to take. Ip also is appropriately critical of the regulatory overreach of Dodd-Frank. BTW, banks would hate my FDIC reform proposal, but it could be combined with the complete repeal of Dodd-Frank.

There are also a few areas where I disagreed with Ip. At one point he wondered why there was so much discussion of the need for monetary stimulus. After all, unemployment in the US and Japan is relatively low, and the unemployment rate in the eurozone is now declining at a decent clip. This is a good argument, but I think he’s also missing something important. Monetary policy must be judged as a regime, not in terms of day-to-day considerations of macroeconomic stability.

For better or worse, central banks now focus most of their effort on inflation targeting, with some attention also paid to keeping unemployment close to the natural rate. Recall that the natural rate hypothesis predicts that the public will eventually adjust their expectations to match any inflation rate, and unemployment will eventually move back to the natural rate. When viewed from this perspective, I think what Greg’s really asking is what difference does it make if the Eurozone has 1% inflation, or 1.9% inflation, as long as it is reasonably steady and as long as unemployment seems to be adjusting back to the natural rate.

I see two problems with the ECB allowing 1% inflation to be the new normal:

1. If this were to occur, the public would lose faith in the ECB’s inflation promises. This would make ECB policy less effective in the next crisis. If central banks are going to set inflation targets, then those targets should mean something. If they decide not to target inflation (as I’d prefer) then it’s essential that they set some other target, such as NGDPLT.

2. If 1.0% inflation, rather than 1.9% inflation, becomes the new normal in the ECB, then nominal interest rates will move to a permanently lower track. And since real interest rates seem to be entering a new normal which is well below the rates we saw in the 20th century, a lower trend rate of inflation would mean that the ECB will be stuck at the zero bound for a much greater percentage of the time. Indeed financial markets are already quite pessimistic about the future course of eurozone rates, especially for safe assets like German and Swiss long-term bonds.

Notice that points 1 and 2 relate to each other; both make it more difficult for the ECB to achieve its goals in the future. So there is real value in taking an announced inflation target seriously, and trying to hit it. BTW, the US is doing much better than the eurozone and Japan on the inflation front, but just today Kocherlakota warned that even the US is likely to fall short of 2% inflation going forward. (I’m a moderate on this question—I think they’ll probably fall a bit short, but perhaps not as much as Kocherlakota and some of my fellow MMs believe. I see something around 1.8% as the new normal.)

At one point Ip asked David the question of what should the Fed actually do to implement an NGDPLT policy regime. I hate these “concrete steppes” questions, but we need to face the fact that this is what everyone wants to know. The reason why I hate these questions is because I know the sort of answer people are looking for:

Desired answer: Some big bazooka of a monetary policy instrument that is so powerful that it can clearly move NGDP to the desired policy path.

My answer: NGDPLT is the big bazooka, and once implemented you merely need to do tiny little OMOs, like we did back before 2008.

And I know that this answer won’t satisfy anyone. They think money has been very easy, and if we’ve fallen short then we must need very, very, very easy policy. We MMs think money has been tight, and that a NGDPLT target could be hit with the sort of moderate policy we had before 2008. In other words, if 5% NGDPLT were adopted in 2007, or right now, the policy would look pretty much like what you saw in Australia after 2007, or what you see in Australia today. Positive interest rates.

But yes, you do need a big “instrument” bazooka lurking in the background, just in case. That makes the system credible, so that you don’t actually have to use it. For David the big bazooka is the Treasury, promising to do a coordinated fiscal/monetary expansion if the Fed runs out of ammo. For me the big bazooka is a Fed promise to buy any and all financial assets, anywhere in the world, until market expectations of NGDP growth are equal to 5% (or whatever the target chosen.)

And the other point I always make is that the lower the NGDP target (i.e. the lower the trend inflation rate) the bigger the Fed balance sheet as a share of GDP. If NGDP growth is so low that nominal rates fall to zero, then the Fed balance sheet can get very large. If the NGDP target rate is set high enough where rates stay above zero, then the Fed balance sheet stays small. I prefer a small Fed balance sheet.

Inflation or socialism? It’s your choice.

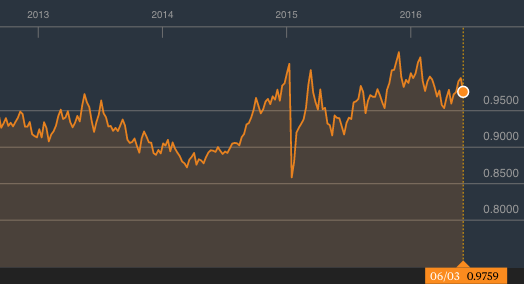

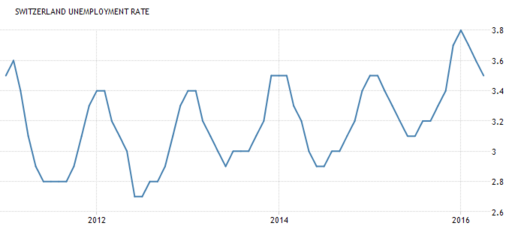

Fortunately, unemployment rose only modestly, as the Swiss economy has always been more flexible than other European economies:

Fortunately, unemployment rose only modestly, as the Swiss economy has always been more flexible than other European economies: (Sorry, I could not find seasonally adjusted data, but you can see the mild upswing in unemployment.)

(Sorry, I could not find seasonally adjusted data, but you can see the mild upswing in unemployment.)