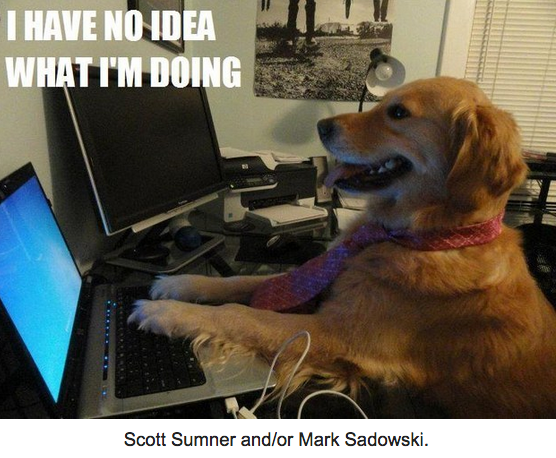

I’m in Jason Smith’s doghouse

Jason Smith is trained in physics, and has recently tried his hand at economics blogging. Perhaps inspired by Matt Yglesias and Britmouse, Jason noticed that an economics degree is not required to do good economic analysis. But he went even further than the other two, creating a revolutionary new type of economics called “Information Transfer Economics.” Although I’ve tried to understand his model, it’s all way over my head. He knows a lot more math than I do.

Jason is now discovering just how macro research is done, and as a result Mark Sadowski and I are in his doghouse. Literally:

And that picture is one of the nicer things he had to say. The dog is more handsome than I am, and probably more skilled at time series analysis. But this isn’t too nice:

And that picture is one of the nicer things he had to say. The dog is more handsome than I am, and probably more skilled at time series analysis. But this isn’t too nice:

This is just garbage analysis.

Basically we did not provide the best possible study of austerity. For instance, we did not distinguish between countries at the zero bound, and those not at the zero bound. Guilty as charged.

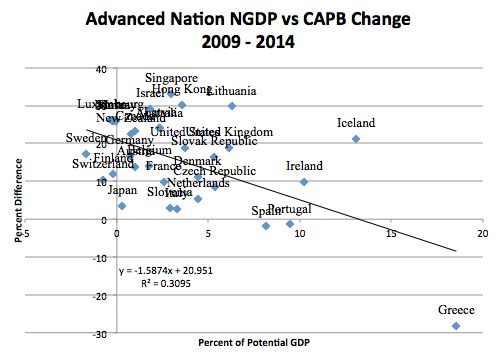

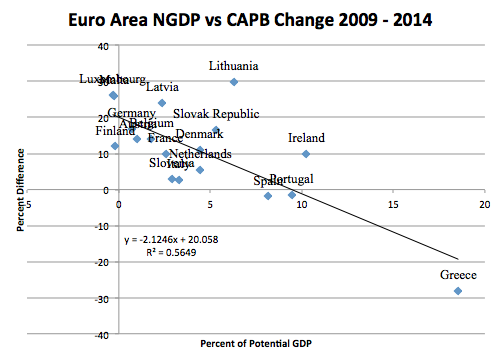

So what’s my defense? Here’s how I look at it. The Keynesians did several studies of the relationship between austerity and growth that were highly flawed, for too many reasons to mention. Confusing real and nominal GDP. Mixing countries with and without an independent central bank. Wrongly assuming correlation implied causality. Mixing countries at the zero bound with countries not at the zero bound. Just a big mess.

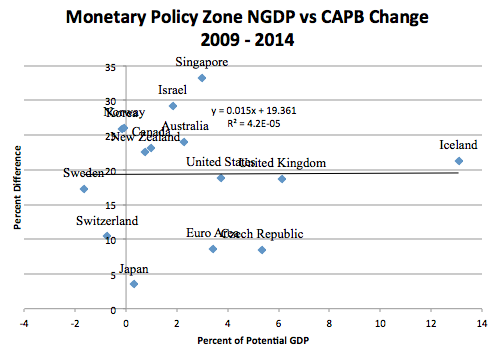

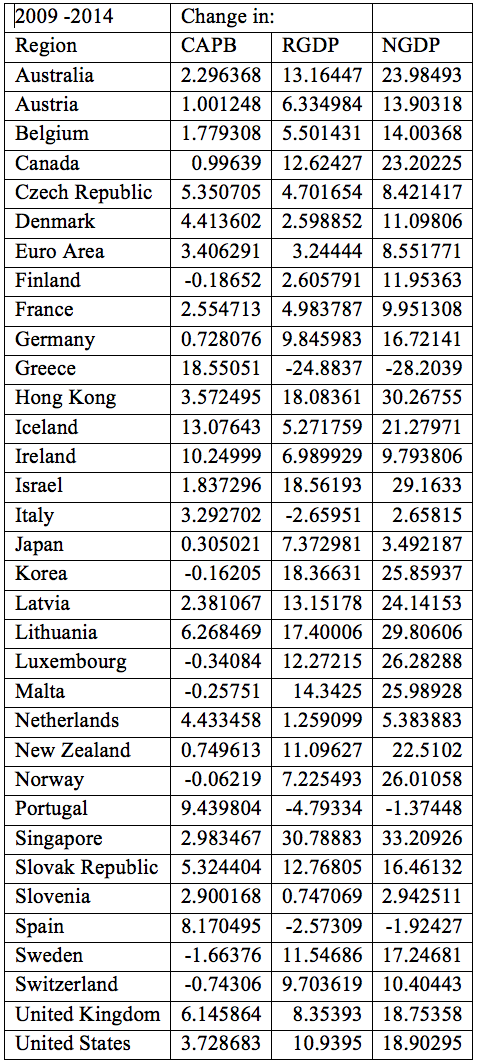

And then the Keynesians did blog posts suggesting that these studies provided some sort of scientific justification for the claim that austerity slows growth. Mark and I thought it would be interesting to at least separate out the countries with an independent central bank, from those that lacked the ability to do monetary offset (i.e. the eurozone countries.)

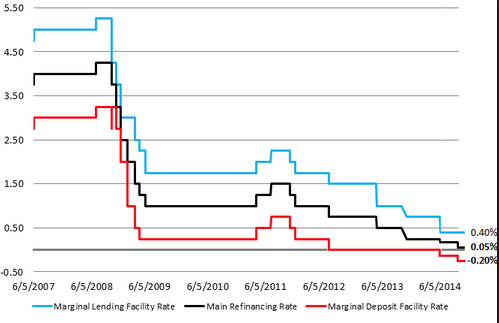

I find it interesting that our critics are outraged that we included some non-zero bound countries, when the Keynesians did as well. For instance, the 18 eurozone countries were certainly not at the zero bound for the vast majority of this period. Their main interest rate fluctuated between 0.75% and 1.50% between early 2009 and 2013. (It’s now roughly zero) And yet all that time Keynesians were squawking about how “austerity” was slowing growth in Europe. It seemed logical to assume that if the Keynesians were making this claim, then they were assuming that their model also applied to countries with low but positive interest rates. Indeed that they assumed it even applied to countries where the central bank was in the process of raising interest rates to reduce inflation. I’m happy throwing out the 18 eurozone countries. But of course if you do so then the empirical support for their austerity theory collapses. Is that what my critics want?

Mark improved on previous studies by looking at both NGDP and RGDP, and by separating out countries with independent monetary policies from those that lack independent monetary policies. He showed that if you do so then the Keynesian results go away. Maybe even further improvements could resurrect the Keynesian model. If so, I’ll take a look at the results. But as of now I don’t know of any credible support for Keynesian interpretation of the effects of austerity during the Great Recession.

PS. Mark has another good post over at Marcus Nunes’ blog.

PPS. The graph below shows ECB rates, with the middle one usually cited as the policy rate. The lower (deposit) rate did hit zero in 2012, but there is no zero bound on the deposit rate. The increase in rates during 2011 was done to control inflation, and eventually caused a double dip recession. Doing fiscal stimulus when a central bank is trying to reduce inflation is about as effective as slamming your foot on the accelerator when the transmission is in neutral.