America’s industrial boom (what is it telling us?)

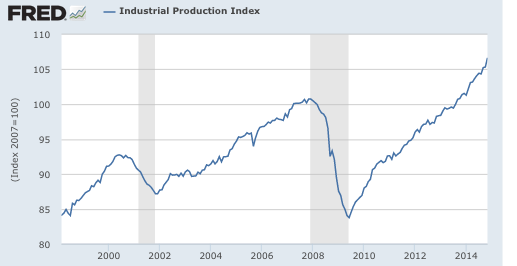

Over the past few years I’ve done a few posts on an underreported story, the fact that industrial production (IP) has been rising much faster than RGDP during the recovery. Early on I argued that this was evidence that a cyclical recovery was actually occurring, and that this refuted those who argued otherwise by pointing to the low LFPR. (It also suggests that tight money, not re-allocation out of housing, caused the recession.) Recently the industrial recovery has gained momentum, so much so that it can no longer be brushed aside. Before discussing what it means, consider that IP was up 1.3% in November, and is up nearly 6% since August 2013. By comparison IP only rose by a total of about 9% during the entire period from the 2000 peak to the 2007 peak. The level is still mediocre, but the momentum is undeniable. The new IP figures seem to confirm the strong November employment data; the economy is now recovering at a faster rate.

So what does the IP boom tell us? First let’s recall that IP includes mostly manufacturing, but also mining and utilities. I prefer the IP aggregate, because when people wring their hands about the loss of “muscular” jobs in manufacturing for men without a college education, it’s clear they are concerned about blue collar jobs in general, including coal mining, oil drilling, etc. In any case, the manufacturing data are quite similar.

So what does the IP boom tell us? First let’s recall that IP includes mostly manufacturing, but also mining and utilities. I prefer the IP aggregate, because when people wring their hands about the loss of “muscular” jobs in manufacturing for men without a college education, it’s clear they are concerned about blue collar jobs in general, including coal mining, oil drilling, etc. In any case, the manufacturing data are quite similar.

First some international comparisons. In the US, IP is up more that 73% in the past 25 years. In Japan it fell by 1.5%. Some of that is population, but not all. After all, Japan’s population is higher than it was 25 years ago, and America’s has risen by roughly 30%, not 73%. America industrializes as Japan de-industrializes. Germany reunified 25 years ago, which might affect the data, but their IP is up only about 30% since 1991. France is up only 9% in 25 years. (The 35-hour workweek?). Britain is similar to Japan, down by about 1%. (Falling North Sea oil output?) Italy is down 11.2% in 25 years. (Berlusconi spending too much time at orgies?) It’s the US that stands out as an industrial power, at least if the data is correct. (I suspect it is not—too much hedonics?)

So what’s wrong with American manufacturing? Jobs, jobs, and jobs. In recent decades we’ve been losing jobs at a rapid rate.

And why have we been losing jobs at a rapid rate? Some people point to imports from China. But the recent IP data suggests that’s not the problem. We are an industrial juggernaut. The problem is quite simple:

It’s the PRODUCTIVITY, stupid.

Agriculture went through this in the late 19th century and early 20th century. And now it’s manufacturing’s turn.

Update: US capacity utilization pushed above 80% in November, roughly the rate during the 2005-07 boom. We need more service sector jobs.

Update#2: I erred in saying the manufacturing numbers were similar. I was lulled by the fact that they have also been rising rapidly in the past year. But commenter allen pointed out that manufacturing has only just regained the 2007 peak, and that oil and gas output (part of mining) have grown much faster.

HT: am