Further thoughts on “inflation”

Nick left the following comment on the previous post:

I really like this post … So I’m sorry to snark … But:

‘I concluded inflation is real.’

And

‘That’s why I keep claiming that inflation is a meaningless concept.’Me think Econ no fit words good sometime.

What can I say? I suppose I was thinking about this in two different ways:

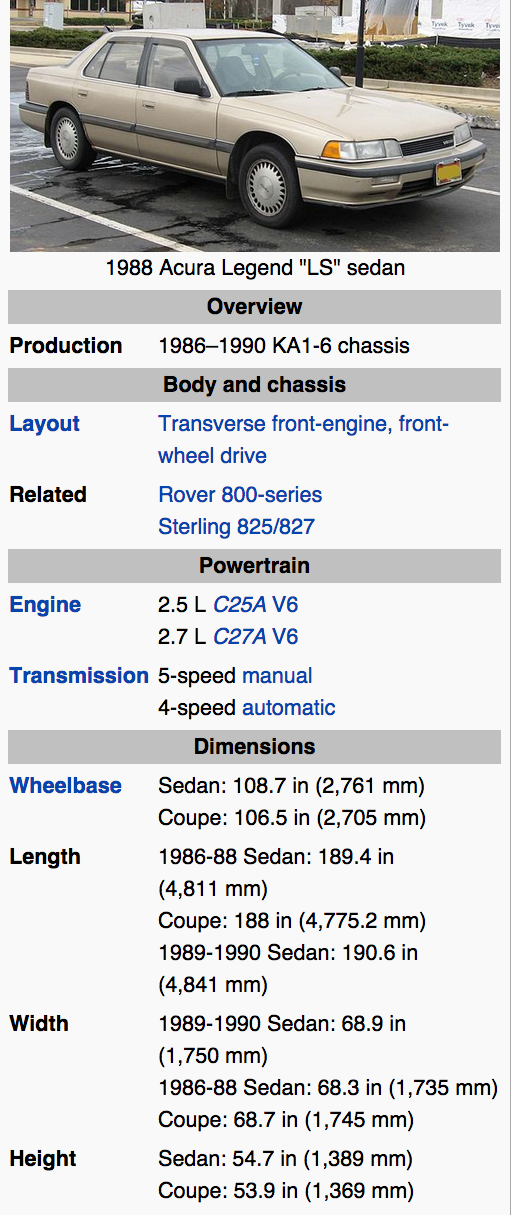

1. The BLS tries to do “hedonic” adjustments to the CPI, i.e. adjust for product quality change. I showed that when we really did have high inflation you’d see the prices of ordinary items like cars rise very rapidly. That’s clearly not true today. I also showed that using what I thought was a plausible hedonic comparison (the 2014 Accord is just as good as the 1986 Legend) you could get zero inflation in new car prices, far less that the 35% assumed by the BLS. So I’m dubious that the BLS is grossly understating inflation. Of course I acknowledge that lots of service prices have risen faster than car prices, and thus there has been some inflation. Even so, using the BLS hedonic approach, the actual BLS numbers seem plausible.

However . . .

2. When I say inflation is a meaningless concept I’m suggesting that the concept is not well defined, despite the BLS’s attempts to do so. Here’s commenter Vivian making a very good point:

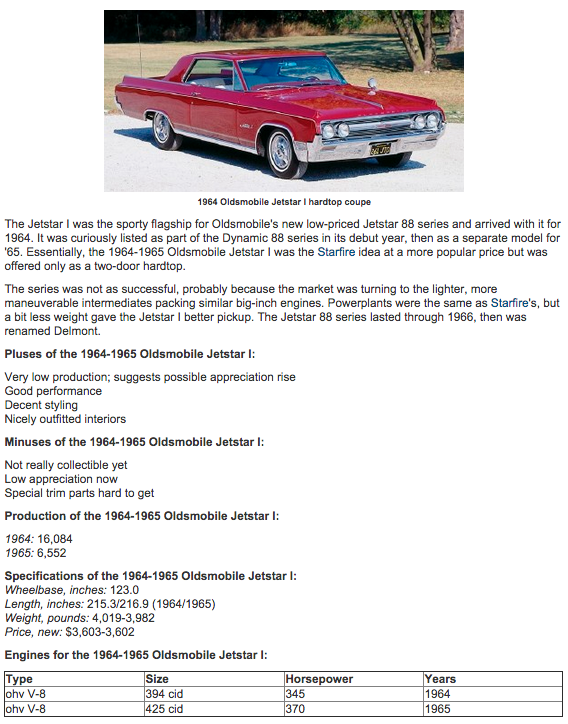

Taking literally, “hedonic” means relating to pleasure. Did you get more or less pleasure from that 1964 Olds with all its trunk and leg space, steel and chrome and its muscular engine than you would from the Accord? What would it cost today, even with our advances in manufacturing technology, to reproduce that 1964 Olds with the same specs? Are hedonic adjustments confusing functionality with price (or even pleasure)?

These are all debatable questions, and for this reason I doubt the statement “there is no such thing as true inflation rate” is debatable.

In earlier posts I’ve made an argument (similar to Vivian’s and almost the opposite of my previous post)–that if you use a sort of “pleasure” criterion, then price inflation is roughly equal to wage inflation, and living standards haven’t risen at all. Thus people used to get great pleasure from crummy black and white TVs, but now someone with that TV set would be miserable, thinking about the great big flat panel HDTV his neighbor has. He’d feel poor. If economists really believe the CPI is supposed to measure a constant utility level, then for all we know there might have been no real wage gains in the past 100 years. Who’s to say if people are happier than 100 years ago? All of these concepts are so slippery that I’m very skeptical of the notion that there is any “true” rate of inflation.

But my previous post was sort of saying; “if we are going to play the game of trying to seriously estimate inflation using BLS hedonic-type approaches, there is no reason to doubt their claim that inflation has slowed sharply from the Great Inflation period.” Nice quality cars went from $3600 to $22,500 in 22 years, then to $22,105 in 28 more years. You can quibble about the models I chose, but the overall pattern is clear. Inflation has slowed sharply. Or should I say “inflation” has slowed sharply? I don’t seem to be able to make up my mind.