In the past, Stephen Williamson has attracted some fierce criticism for his views on the relationship between money and interest rates, specifically some posts that seemed to deny the importance of the “liquidity effect.” Nick Rowe and others criticized Williamson for seeming to suggest that a Fed policy of lowering interest rates would actually lower the rate of inflation–via the Fisher effect. Williamson has a new post that seems to have somewhat more conventional views of the liquidity effect, but still emphasizes the longer term importance of the Fisher effect:

If the central bank experiments with random open market operations, it will observe the nominal interest rate and the inflation rate moving in opposite directions. This is the liquidity effect at work – open market purchases tend to reduce the nominal interest rate and increase the inflation rate. So, the central banker gets the idea that, if he or she wants to control inflation, then to push inflation up (down), he or she should move the nominal interest rate down (up).

But, suppose the nominal interest rate is constant at a low level for a long time, and then increases to a higher level, and stays at that higher level for a long time. All of this is perfectly anticipated. Then, there are many equilibria, all of which converge in the long run to an allocation in which the real interest rate is independent of monetary policy, and the Fisher relation holds.

Before discussing Williamson, let me point out that back in 2008-09, 99.9% of economists thought the Fed had eased policy, and that the deflation of 2009 occurred in spite of those heroic easing attempts. That 99.9% included the older monetarists. Only the market monetarists and the ghost of Milton Friedman insisted that money was tight and that interest rates were falling due to the income and Fisher effects. I’d like to think that Williamson agrees with us, but of course he’d be horrified by the specifics on the MM model, indeed he wouldn’t even recognize it as a “model.”

Williamson continues:

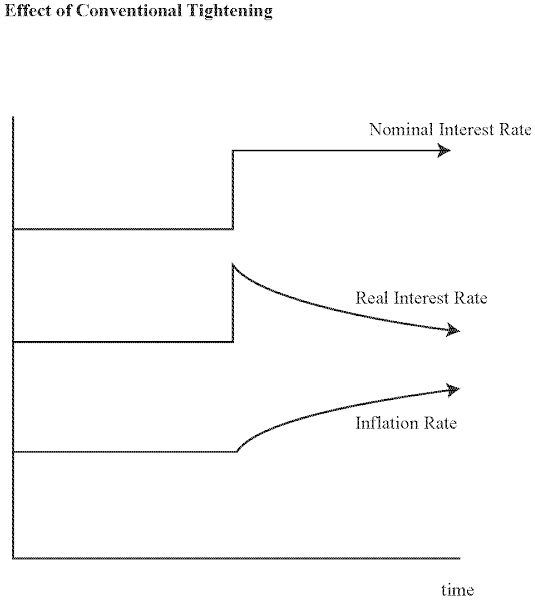

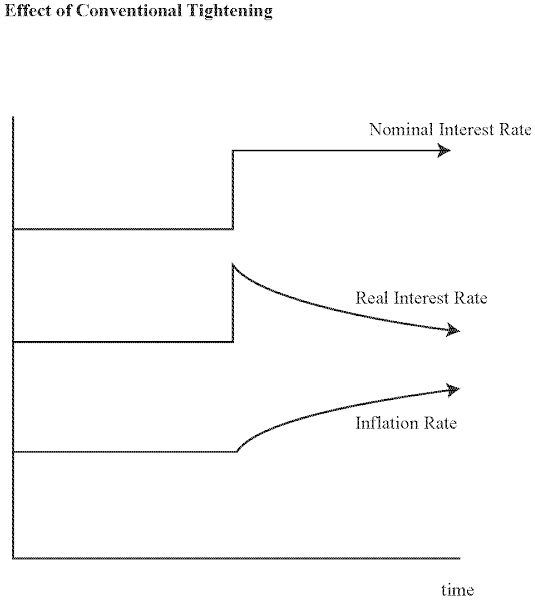

A natural equilibrium to look at is one that starts out in the steady state that would be achieved if the central bank kept the nominal interest rate at the low value forever. Then, in my notes, I show that the equilibrium path of the real interest rate and the inflation rate look like this:

Is that really monetary tightening? After all, inflation rises. Here’s the very next paragraph by Williamson:

There is no impact effect of the monetary “tightening” on the inflation rate, but the inflation rate subsequently increases over time to the steady state value – in the long run the increase in the inflation rate is equal to the increase in the nominal rate. The real interest rate increases initially, then falls, and in the long run there is no effect on the real rate – the liquidity effect disappears in the long run. But note that the inflation rate never went down.

The scare quotes around “tightening” suggest that Williamson is also skeptical of the notion that tightening has actually occurred. Indeed inflation increased, then policy must have eased. However to his credit he recognizes that “conventional wisdom” would have viewed this as a tightening. Nonetheless the final part of the paragraph has me concerned. Williamson refers to the disappearance of the liquidity effect, but in the example he graphed there is no liquidity effect, as the rise in interest rates was not caused by a tightening of monetary policy. If it had been caused by tighter money, inflation would have fallen.

So how can the graph be explained? As far as I can tell the most likely explanation is that at the decisive moment (call it t=0) the equilibrium Wicksellian interest rate jumps much higher, and then gradually returns to a lower level over the next few years. And the central bank moves the policy rate to keep the price level well behaved. I suppose you might see this as being roughly the opposite of the shock that hit the developed economies in 2008, except of course it was more gradual.

Suppose there had been no change in the Wicksellian equilibrium rate, and the central bank simply increased the policy rate by 100 basis points, and kept it at the higher level. In that case, the economy would have fallen into hyperdeflation. When you peg interest rates in an unconditional fashion, the price level becomes undefined.

Is there any other way that one could get a path like the one shown by Williamson? Could the central bank initiate this new path? Maybe, at least if you don’t assume a discontinuous change in the interest rate, followed by absolute stability. To explain how you could get roughly this sort of path lets look at the reverse case.

Suppose the Fed had been increasing the monetary base at about 5% a year for many years, and the markets expected this to continue. This led to roughly 5% NGDP growth. The markets assumed the Fed was implicitly targeting NGDP growth at about 5%. But the Fed actually also cared about headline inflation, which suddenly rose higher than desired (due to an oil shock.) The Fed responded by holding the base constant for a period of 9 months. (For those who don’t know, so far I’ve described events up to May 2008.)

This unexpectedly tight money turned market expectations more bearish. As expectations for NGDP growth became more bearish, the asset markets fell and the Fed responded by cutting interest rates. And since inflation did not immediately decline, real short term rates also fell (still the mirror image of the Williamson graph.) BTW, we know that even 3 month T-bill yields FELL on the news of policy tightening at the December 2007 FOMC meeting. Williamson would have approved of that market reaction!!

Normally the Fed would have realized its mistake at some point, and monetary policy would have nudged us back onto the old path. In this case, however, market rates had fallen to zero by the time the Fed realized its mistake. And the Fed was reluctant to do unconventional stimulus. There was a permanent reduction in the trend rate of NGDP growth, as well as nominal interest rates. This showed up in lower than normal 30-year bond yields. The process played out even more dramatically in Europe (and earlier in Japan.)

I do have one quibble with the Williamson post. He seems too skeptical of the claim that the ECB recently eased policy. But before I criticize him let me say that I find his error much more forgivable than the conventional wisdom, which views low interest rates as easy money.

Williamson points out that the ECB recently cut rates, and that if the ECB leaves rates near zero for an extended period of time, then inflation is likely to stay very low, as in Japan. All of this is correct. But I think he overlooks the fact that while the overall policy regime in Europe is relatively “tight”; the specific recent actions taken by the ECB most definitely were “easing.” We know that because the euro clearly fell in the forex markets in response to that action.

I think this puzzles a lot of pundits. It’s very possible for central banks to take relative weak actions that are by themselves expansionary, even while leaving the overall policy stance contractionary, albeit a few percent less so than before. That’s the story of the various QE programs in America.

I encourage all bloggers to never reason from a price change. Do not draw out a path of interest rates and ask what sort of policy it is. First ask what caused the interest rates to change—the liquidity effect, or the income/Fisher effects?

PS. Of course I agree with most of the Williamson post, such as his criticism of “overheating” theories of inflation.

HT: TravisV