Mike Sproul has a new post (at JP Koning) that compares his “backing” theory of the value of money with my “quantity theoretic” approach. (Just to be clear, market monetarism does not assume V is fixed, like some simple textbook models of the QTM.)

I’ve argued that US base money was once backed by gold, but no longer has any meaningful backing. It’s not really a liability of the Fed. Mike responds:

Scott’s argument is based on gold convertibility. On June 5, 1933, the Fed stopped redeeming FRN’s for a fixed quantity of gold. On that day, FRN’s supposedly stopped being the Fed’s liability. But there are at least three other ways that FRN’s can still be redeemed: (i) for the Fed’s bonds, (ii) for loans made by the Fed, (iii) for taxes owed to the federal government. The Fed closed one channel of redemption (the gold channel), while the other redemption channels (loan, tax, and bond) were left open.

The ability to redeem dollars for government bonds, at the going market price of bonds, has very different implications from the ability to redeem cash for a real good like gold, at a fixed nominal price. I’d prefer to say cash can be “spent” on bonds, just as cash can be spent on cars or TVs. Indeed even during the Zimbabwe hyperinflation, the Zimbabwe dollar could still be “redeemed” for gold at the going market price of gold in terms of Zimbabwe dollars. But that fact has no implications for the value of the Zimbabwe dollar. If you increase the quantity of Zimbabwe dollars their value will fall, as they will buy fewer ounces of gold. In contrast, before 1933 an increase in the quantity of US base money did not impact the amount of gold that could be purchased with one dollar (it was 1/20.67 ounces). That’s the sort of “redemption” that matters for the price level.

Once we understand that both convertible and inconvertible FRN’s are a true liability of the Fed, it is easy to see that the quantity of inconvertible FRN’s could also be increased by any amount, and as long as the Fed’s assets rose in step, there would be no effect on the value of the dollar. (There is a comparable result in Finance theory: that the value of a convertible call option is equal to the value of an inconvertible call option.)

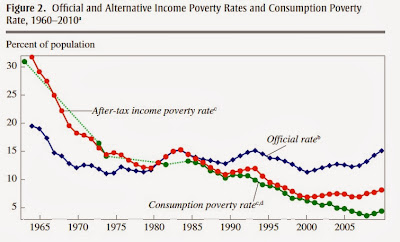

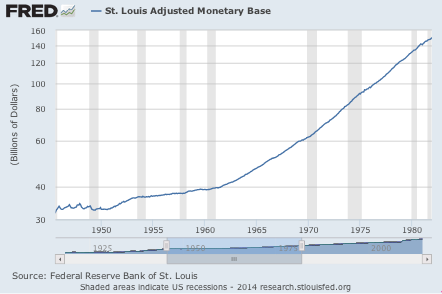

I don’t agree. If the Fed doubles the monetary base by purchasing an equal amount of government debt at going market prices, the price level will double in the long run. This is why I don’t accept the backing theory–I believe it is rejected by the evidence. Here’s just one example. In the early 1960s “Phillips Curve” ideology took root in America. It was (erroneously) decided that we could trade-off more inflation for less unemployment. So the Fed exogenously increased the monetary base at a much faster rate after 1962. At first RGDP growth rose, then both RGDP and inflation, but eventually all we got was the Great Inflation, with no extra output.

We can also observe the inflationary impact of open market purchases of bonds by looking at the response of financial market indicators. If OMOs didn’t matter because the new money was fully backed, then financial markets would shrug off any Fed money printing. Indeed we can ask how central banks were able to achieve roughly 2% inflation once they set their minds to it. Keep in mind that 2% inflation is not “normal.” There is no normal inflation rate. Inflation averaged zero percent under the gold standard, and 8% from 1972 to 1981. Then about 4% from 1982 to 1991. Much more in some other countries. There is no normal rate of inflation. In a related note, here’s Nick Rowe criticizing John Cochrane’s fiscal theory of the price level:

The Bank of Canada has been paying interest on reserves for 20 years. And when it wants to increase the inflation rate, because it fears inflation will fall below the 2% target if it does nothing, the Bank of Canada lowers the interest rate on reserves. And the Bank of Canada seems to have gotten the sign right, because it has hit the 2% inflation target on average, which would be an amazing fluke it if had been turning the steering wheel the wrong way for the last 20 years without going off in totally the wrong direction.

The Great Inflation was certainly not caused by deficits, which became much larger after 1981, precisely when the Great Inflation ended. It was caused by printing money and buying bonds with the newly-issued money.

Mike continues:

But if the Fed issued billions of new dollars in exchange for assets of equal value, then I’d say there would be no inflation as long as the new dollars were fully backed by the Fed’s newly acquired assets. I’d also add a few words about how those dollars would only be issued if people wanted them badly enough to hand over bonds or other assets equal in value to the FRN’s that they received from the Fed.

This is where things get sticky, because Scott would once again agree that under these conditions, there would be no inflation. Except that Scott would say that the billions of new dollars would only be issued in response to a corresponding increase in money demand.

No, that is not my view. The Fed might well increase the money supply even if the real demand for money did not rise. There is always some price of bonds at which the Fed can induce people to exchange bonds for cash, even if they do not want to hold larger real cash balances. They’ll spend the new cash almost immediately after being paid for the bonds. That’s the famous “hot potato effect” that underlies the quantity theory. I’d point to the 1960s and 1970s as an example of the Fed injecting new money in the economy far beyond any increase in desired real cash balances.

Scott is clearly wrong when he says that the backing theory doesn’t have much predictive power. It obviously has just as much predictive power as Scott’s theory, since every episode that can be explained by Scott’s theory can also be explained by my theory.

This is a tough one, because the identification problem is obviously a big problem in macro. Not everyone might accept my claim that the Great Inflation was caused by an exogenous increase in the base, or my interpretation of market reactions to money announcement shocks, or my claim that successful 2% inflation targeting supports the assumption that Fed OMOs influence the price level. But I wouldn’t say the QTM has no extra predictive power, rather it has predictive power that might be contested. Central bankers would be in the best position to test the theory, as they can engineer exogenous changes if they wish. I suspect that fact explains why most central bankers don’t adhere to the backing theory. They think they see signs of their power.

Mike ends with 4 specific objections to the QTM:

(i) The rival money problem. When the Mexican central bank issues a paper peso, it will get 1 peso’s worth of assets in return. The quantity theory implies that those assets are a free lunch to the Mexican central bank, and that they could actually be thrown away without affecting the value of the peso. This free lunch would attract rival moneys.

We occasionally do observe rival monies taking hold during extreme hyperinflation. The mystery is why doesn’t it happen with other inflation episodes. Fiat currencies have survived some pretty high rates of trend inflation, especially in Latin America. My best guess is the answer is “network effects.” There are huge efficiency gains from using a single currency in a given region. It’s hard to dislodge the incumbent.

(ii) The counterfeiter problem. If the Fed increased the quantity of FRN’s by 10% through open-market operations, the quantity theory predicts about 10% inflation. If the same 10% increase in the money supply were caused by counterfeiters, the quantity theory predicts the same 10% inflation. In this topsy-turvy quantity theory world, the Fed is supposedly no better than a counterfeiter, even though the Fed puts its name on its FRN’s, recognizes those FRN’s as its liability, holds assets against those FRN’s, and stands ready to use its assets to buy back the FRN’s that it issued.

When I teach monetary economics I ask my students to think of the Fed as a counterfeiter. I say that’s the best way to understand monetary economics. And there is some ambiguity to the “stands ready” in the final line of the quotation. Was that true during the Great Inflation?

(iii) The currency buy-back problem. Quantity theorists often claim that central banks don’t need assets, since the value of the currency is supposedly maintained merely by the interaction of money supply and money demand. But suppose the demand for money falls by 20%. If the central bank does not buy back 20% of the money in circulation, then the quantity theory says that the money will fall in value. But then it becomes clear that the central bank does need assets, to buy back any refluxing currency. And since the demand for money could fall to zero, the central bank must hold enough assets to buy back 100% of the money it has issued. In other words, even the quantity theory implies that the central bank must back its money.

There are two ways to address this. One possibility is that the central bank does not reduce the base when needed to hit a particular inflation target. That describes the 1960s and 1970s. But what about when they are successfully targeting inflation at 2%? In that case they’d need some assets to do open market sales, but they might well get by with far less than 100% backing. The last point (about a 100% fall in money demand) feeds into his final objection:

(iv) The last period problem. I’ll leave this one to David Glasner:

“For a pure medium of exchange, a fiat money, to have value, there must be an expectation that it will be accepted in exchange by someone else. Without that expectation, a fiat money could not, by definition, have value. But at some point, before the world comes to its end, it will be clear that there will be no one who will accept the money because there will be no one left with whom to exchange it. But if it is clear that at some time in the future, no one will accept fiat money and it will then lose its value, a logical process of backward induction implies that it must lose its value now.”

There are two possibilities here. One is that the public never believes the world will lend with certainty, rather that each year there is a 1/1000 chance of the world ending. In that case people would still hold cash as long as the liquidity benefits exceeded 0.10% (10 basis points), which seems quite plausible given the fact that people still hold substantial quantities of cash when inflation reaches double digits.

Now let’s consider a case with a definite end of the road, say the German mark or French franc in 2001. In that case the public would expect redemption for a alternative asset with a relatively similar real value (euros in the case.) I’m actually not sure whether it matters if the central bank holds the assets used for redemption, rather than some other institution like the Treasury. But yes, they would expect some sort of backing in that case. But even so, OMPs will still be inflationary, which contradicts the claims made by backing proponents.

One final point. We all agree that gold need not be “backed” to have value. The QTM implicitly thinks of cash as a sort of paper gold. It’s a real asset that has value because it provides liquidity services. As an analogy, gasoline makes cars go. Motor oil doesn’t propel a car forward. But motor oil has value because it lubricates engine parts. It’s harder to model the value of motor oil than gasoline, because the advantages are less obvious. Similarly, it’s harder to model the value of cash than gold or houses or stocks. But cash lubricates transactions, and hence a medium of exchange has value. But once you have that monetary system in place, having twice as much cash adds no extra value. Instead all prices double, and the value of cash falls in half. It’s the monetary system that has real value.