Reply to Mike Sproul

Mike Sproul has a new post (at JP Koning) that compares his “backing” theory of the value of money with my “quantity theoretic” approach. (Just to be clear, market monetarism does not assume V is fixed, like some simple textbook models of the QTM.)

I’ve argued that US base money was once backed by gold, but no longer has any meaningful backing. It’s not really a liability of the Fed. Mike responds:

Scott’s argument is based on gold convertibility. On June 5, 1933, the Fed stopped redeeming FRN’s for a fixed quantity of gold. On that day, FRN’s supposedly stopped being the Fed’s liability. But there are at least three other ways that FRN’s can still be redeemed: (i) for the Fed’s bonds, (ii) for loans made by the Fed, (iii) for taxes owed to the federal government. The Fed closed one channel of redemption (the gold channel), while the other redemption channels (loan, tax, and bond) were left open.

The ability to redeem dollars for government bonds, at the going market price of bonds, has very different implications from the ability to redeem cash for a real good like gold, at a fixed nominal price. I’d prefer to say cash can be “spent” on bonds, just as cash can be spent on cars or TVs. Indeed even during the Zimbabwe hyperinflation, the Zimbabwe dollar could still be “redeemed” for gold at the going market price of gold in terms of Zimbabwe dollars. But that fact has no implications for the value of the Zimbabwe dollar. If you increase the quantity of Zimbabwe dollars their value will fall, as they will buy fewer ounces of gold. In contrast, before 1933 an increase in the quantity of US base money did not impact the amount of gold that could be purchased with one dollar (it was 1/20.67 ounces). That’s the sort of “redemption” that matters for the price level.

Once we understand that both convertible and inconvertible FRN’s are a true liability of the Fed, it is easy to see that the quantity of inconvertible FRN’s could also be increased by any amount, and as long as the Fed’s assets rose in step, there would be no effect on the value of the dollar. (There is a comparable result in Finance theory: that the value of a convertible call option is equal to the value of an inconvertible call option.)

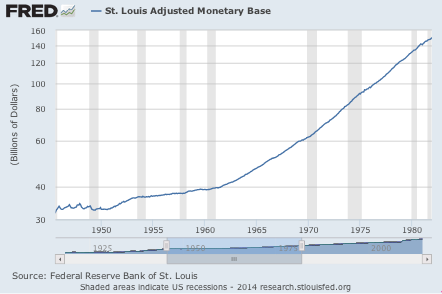

I don’t agree. If the Fed doubles the monetary base by purchasing an equal amount of government debt at going market prices, the price level will double in the long run. This is why I don’t accept the backing theory–I believe it is rejected by the evidence. Here’s just one example. In the early 1960s “Phillips Curve” ideology took root in America. It was (erroneously) decided that we could trade-off more inflation for less unemployment. So the Fed exogenously increased the monetary base at a much faster rate after 1962. At first RGDP growth rose, then both RGDP and inflation, but eventually all we got was the Great Inflation, with no extra output.

We can also observe the inflationary impact of open market purchases of bonds by looking at the response of financial market indicators. If OMOs didn’t matter because the new money was fully backed, then financial markets would shrug off any Fed money printing. Indeed we can ask how central banks were able to achieve roughly 2% inflation once they set their minds to it. Keep in mind that 2% inflation is not “normal.” There is no normal inflation rate. Inflation averaged zero percent under the gold standard, and 8% from 1972 to 1981. Then about 4% from 1982 to 1991. Much more in some other countries. There is no normal rate of inflation. In a related note, here’s Nick Rowe criticizing John Cochrane’s fiscal theory of the price level:

The Bank of Canada has been paying interest on reserves for 20 years. And when it wants to increase the inflation rate, because it fears inflation will fall below the 2% target if it does nothing, the Bank of Canada lowers the interest rate on reserves. And the Bank of Canada seems to have gotten the sign right, because it has hit the 2% inflation target on average, which would be an amazing fluke it if had been turning the steering wheel the wrong way for the last 20 years without going off in totally the wrong direction.

The Great Inflation was certainly not caused by deficits, which became much larger after 1981, precisely when the Great Inflation ended. It was caused by printing money and buying bonds with the newly-issued money.

Mike continues:

But if the Fed issued billions of new dollars in exchange for assets of equal value, then I’d say there would be no inflation as long as the new dollars were fully backed by the Fed’s newly acquired assets. I’d also add a few words about how those dollars would only be issued if people wanted them badly enough to hand over bonds or other assets equal in value to the FRN’s that they received from the Fed.

This is where things get sticky, because Scott would once again agree that under these conditions, there would be no inflation. Except that Scott would say that the billions of new dollars would only be issued in response to a corresponding increase in money demand.

No, that is not my view. The Fed might well increase the money supply even if the real demand for money did not rise. There is always some price of bonds at which the Fed can induce people to exchange bonds for cash, even if they do not want to hold larger real cash balances. They’ll spend the new cash almost immediately after being paid for the bonds. That’s the famous “hot potato effect” that underlies the quantity theory. I’d point to the 1960s and 1970s as an example of the Fed injecting new money in the economy far beyond any increase in desired real cash balances.

Scott is clearly wrong when he says that the backing theory doesn’t have much predictive power. It obviously has just as much predictive power as Scott’s theory, since every episode that can be explained by Scott’s theory can also be explained by my theory.

This is a tough one, because the identification problem is obviously a big problem in macro. Not everyone might accept my claim that the Great Inflation was caused by an exogenous increase in the base, or my interpretation of market reactions to money announcement shocks, or my claim that successful 2% inflation targeting supports the assumption that Fed OMOs influence the price level. But I wouldn’t say the QTM has no extra predictive power, rather it has predictive power that might be contested. Central bankers would be in the best position to test the theory, as they can engineer exogenous changes if they wish. I suspect that fact explains why most central bankers don’t adhere to the backing theory. They think they see signs of their power.

Mike ends with 4 specific objections to the QTM:

(i) The rival money problem. When the Mexican central bank issues a paper peso, it will get 1 peso’s worth of assets in return. The quantity theory implies that those assets are a free lunch to the Mexican central bank, and that they could actually be thrown away without affecting the value of the peso. This free lunch would attract rival moneys.

We occasionally do observe rival monies taking hold during extreme hyperinflation. The mystery is why doesn’t it happen with other inflation episodes. Fiat currencies have survived some pretty high rates of trend inflation, especially in Latin America. My best guess is the answer is “network effects.” There are huge efficiency gains from using a single currency in a given region. It’s hard to dislodge the incumbent.

(ii) The counterfeiter problem. If the Fed increased the quantity of FRN’s by 10% through open-market operations, the quantity theory predicts about 10% inflation. If the same 10% increase in the money supply were caused by counterfeiters, the quantity theory predicts the same 10% inflation. In this topsy-turvy quantity theory world, the Fed is supposedly no better than a counterfeiter, even though the Fed puts its name on its FRN’s, recognizes those FRN’s as its liability, holds assets against those FRN’s, and stands ready to use its assets to buy back the FRN’s that it issued.

When I teach monetary economics I ask my students to think of the Fed as a counterfeiter. I say that’s the best way to understand monetary economics. And there is some ambiguity to the “stands ready” in the final line of the quotation. Was that true during the Great Inflation?

(iii) The currency buy-back problem. Quantity theorists often claim that central banks don’t need assets, since the value of the currency is supposedly maintained merely by the interaction of money supply and money demand. But suppose the demand for money falls by 20%. If the central bank does not buy back 20% of the money in circulation, then the quantity theory says that the money will fall in value. But then it becomes clear that the central bank does need assets, to buy back any refluxing currency. And since the demand for money could fall to zero, the central bank must hold enough assets to buy back 100% of the money it has issued. In other words, even the quantity theory implies that the central bank must back its money.

There are two ways to address this. One possibility is that the central bank does not reduce the base when needed to hit a particular inflation target. That describes the 1960s and 1970s. But what about when they are successfully targeting inflation at 2%? In that case they’d need some assets to do open market sales, but they might well get by with far less than 100% backing. The last point (about a 100% fall in money demand) feeds into his final objection:

(iv) The last period problem. I’ll leave this one to David Glasner:

“For a pure medium of exchange, a fiat money, to have value, there must be an expectation that it will be accepted in exchange by someone else. Without that expectation, a fiat money could not, by definition, have value. But at some point, before the world comes to its end, it will be clear that there will be no one who will accept the money because there will be no one left with whom to exchange it. But if it is clear that at some time in the future, no one will accept fiat money and it will then lose its value, a logical process of backward induction implies that it must lose its value now.”

There are two possibilities here. One is that the public never believes the world will lend with certainty, rather that each year there is a 1/1000 chance of the world ending. In that case people would still hold cash as long as the liquidity benefits exceeded 0.10% (10 basis points), which seems quite plausible given the fact that people still hold substantial quantities of cash when inflation reaches double digits.

Now let’s consider a case with a definite end of the road, say the German mark or French franc in 2001. In that case the public would expect redemption for a alternative asset with a relatively similar real value (euros in the case.) I’m actually not sure whether it matters if the central bank holds the assets used for redemption, rather than some other institution like the Treasury. But yes, they would expect some sort of backing in that case. But even so, OMPs will still be inflationary, which contradicts the claims made by backing proponents.

One final point. We all agree that gold need not be “backed” to have value. The QTM implicitly thinks of cash as a sort of paper gold. It’s a real asset that has value because it provides liquidity services. As an analogy, gasoline makes cars go. Motor oil doesn’t propel a car forward. But motor oil has value because it lubricates engine parts. It’s harder to model the value of motor oil than gasoline, because the advantages are less obvious. Similarly, it’s harder to model the value of cash than gold or houses or stocks. But cash lubricates transactions, and hence a medium of exchange has value. But once you have that monetary system in place, having twice as much cash adds no extra value. Instead all prices double, and the value of cash falls in half. It’s the monetary system that has real value.

Tags:

4. June 2014 at 17:14

In coined specie money, debasement can be thought of as self-counterfeiting. But I don’t think that is quite what you mean about the Fed as counterfeiter.

Counterfeiting was why self-contained monetary universes such as the Roman or Han Empires could not make debasement “stick” (i.e. have the brand trump the content, given that coins are branded metal). Counterfeiters would mint “fake” coins until the there was no profit to be made between the brand and the metal content. Point for QTM.

Walter Scheidel has a useful discussion.

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1096440

As for “fiat money will end”, decisions happen in time. If we have no information about when such a certainty will occur, it is not going to feed into our risk assessments in any way that distinguishes one time period from another. Confederate dollars hyper-inflated partly because evidence about specifically when the game of musical chairs was going to stop was mounting dramatically.

But cash lubricates transactions, and hence a medium of exchange has value. But once you have that monetary system in place, having twice as much cash adds no extra value. Instead all prices double, and the value of cash falls in half. It’s the monetary system that has real value. Awfully ambiguous use of the word ‘value’. How about:

But cash lubricates transactions, and hence a medium of exchange has transaction utility–which is a real utility because, in a monetised economy, money permits transactions to take place that otherwise wouldn’t. But once you have that monetary system in place, having twice as much cash adds no extra transaction utility, it just lowers the exchange value of money. Instead all prices double, and the exchange value of cash falls in half. It’s the monetary system that has real utility.

Which then feeds back into the point about hyperinflation and, yes, network effects, because the transaction utility operates within transactions chains that operate within networks that have sufficient information feedback to generate confidence in transaction utility. Which is clearer when considering the range of things that have been used as money:

Shells (especially cowries), beads (whether made of stone, shell, glass or whatever), salt (including stamped salt cakes), cloth (from silk to wadmal, a coarse wool fabric), tool metals (iron, copper, tin, bronze) in various shapes, die cakes, gold dust, weighted gold, teeth, feather coils, strings of coconut discs, carved stone (also a tool material), animal skins, cattle, grain (notably barley and rice), pigs, coconuts, buffaloes, seeds, slaves, silver in lumps or shaped, tea (including in bricks), plaited palm-fibre rings, tobacco, beeswax, camphor, porcelain jars, human heads, cocoa beans, balls of rubber, coca leaves, logwood (mahogany) … (All taken from Alison Hinston Quiggin, A Survey of Primitive Money: the Beginnings of Currency, Metheun, 1949.)

Also used as money:

rum (NSW colony), cigarettes (PoW camps and gaols), tinned fish (non-smoking gaols).

I would stress that human heads were used as money only in really important transactions. Such as making peace between two villages, when appropriate valuables were added to even up the exchange of returned heads. As case of “moneyness” perhaps.

4. June 2014 at 17:47

Very good reply Scott.

Hume: “MONEY is not, properly speaking, one of the subjects of commerce; but only the instrument which men have agreed upon to facilitate the exchange of one commodity for another. It is none of the wheels of trade: It is the oil which renders the motion of the wheels more smooth and easy.”

4. June 2014 at 18:15

If money is convertible, then the issuing bank is disciplined by the threat of a run. If not convertible, then there won’t be a run, but that doesn’t mean that there’s no discipline. People can spend their money. And that would cause hyperinflation (ending in the death of the money) if the bank didn’t have assets. So if the bank wants to credibly promise some form of price stability, it needs assets.

4. June 2014 at 18:25

Okay, great stuff, but as a practical matter, I do have some questions:

1. If you have one nation (the USA) that has a currency accepted globally, and which sources goods, services and labor globally (call centers, anything done by Internet), does a 10 percent increase in the USA money supply really lead to 10 percent inflation?

Since the USA now sources globally (a far cry from the nearly hermetic 1960s) does a 10 percent increase in the money supply just bring a lot of goods, services and labor into our economy, and cause a ripple in global prices?

2. If there is a lot of slack and competition in the economy, does an increase in the money supply just increase output? Are we assuming the economy is going full throttle (although in a global economy, that is hard to imagine) and then we pump out 10 percent more dollars and that is when we get 10 percent inflation?

3. Suppose the Fed prints no new money. But the $1.28 trillion in cash offshore (actually, probably only $1 trillion) is repatriated, due to a clemency law for drug lords. Okay, no new cash printed, but would not the USA see a boom and perhaps inflation? Is this considered a rise in velocity?

5. June 2014 at 02:44

Another way to address the “the currency buy-back problem” for a central bank is to issue own bonds, so in essence converting some of it’s monetary liabilities into illiquid ones. This way the central bank doesn’t need assets at all and can nevertheless manage the size of the monetary base. I think, I read once about a central bank which did just that in the reality, but i don’t know anymore, which one it was.

5. June 2014 at 03:12

Not sure if it matters for the backing theory, but for most large institutions, the book value of “backing” assets isn’t the same as the amount of money that could be recovered if they were all put on the market in a fire sale.

I assume that there is some price in cash low enough that the Fed could unload all of its bonds immediately if it wanted to, but that price would be far lower than current bond prices.

5. June 2014 at 05:21

“We occasionally do observe rival monies taking hold during extreme hyperinflation. The mystery is why doesn’t it happen with other inflation episodes.”

I was under the impression that, in Argentina at least, people tended to hold their daily spending cash in the local currency, pesos or australs. That is the network effect, as you note.

Long-term savings, at least during periods of material inflation, would tend to be placed in US dollars, gold or fixed assets like real estate. Thus, back in the early 1960s, when my mother was a secretary in Buenos Aires, she would run out at lunch time on payday to buy gold, which she converted bank into pesos (I think it was pesos) as she spent it.

5. June 2014 at 07:28

Lorenzo, Very good comment, and yes your version of “value” is more clear.

Nick, I only steal from the best.

Max, I agree.

Ben, 1. Yes, but only in the long run.

2. Output is affected in the short run, prices in the long run.

3. It depends what else the Fed did, in terms of QE, tapering, IOR, etc.

Alex, Let me know if you find a link.

Michael and Steven, Good points.

5. June 2014 at 15:04

Scott, are you familiar with this paper?:

http://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/sr/sr218.pdf

If so, what are your thoughts on it?

5. June 2014 at 18:09

“Instead all prices double, and the value of cash falls in half”

We actually don’t really know this. Sure, we could have P = k M. But we could also have log P = k log M which reduces to the previous equation in the case of small changes in M, but has very different behavior … Doubling M results in 2^k times P.

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2014/06/money-unit-of-information-and-medium-of.html

5. June 2014 at 19:31

Scott: The ability to redeem dollars for government bonds, at the going market price of bonds, has very different implications from the ability to redeem cash for a real good like gold, at a fixed nominal price. I’d prefer to say cash can be “spent” on bonds, just as cash can be spent on cars or TVs.

Mike: Start with a bank that has issued $100 of money, backed by and convertible into 100 oz of silver. That bank might then issue another $2 of currency, backed by and convertible into $2 worth of bonds. Since $1=1 oz, that $2 bond could be sold any time for 2 oz of silver, or for a 2 oz bond denominated in silver, or it could be used to buy back the $2 of currency for which it was originally purchased. The $2 of currency was issued for a bond in the first place, and it can be redeemed for bonds. Simply changing the denomination of a bank’s assets does not affect its financial position.

This process of “backing a dollar with another dollar” does have its limits. There must be some physical assets anchoring the dollar. In this example the physical asset is the 100 oz of silver. In the case of the US dollar, the physical assets include the Fed’s gold and office buildings, in addition to the US government’s ability to take physical property from us through taxation.

Scott: The Great Inflation was certainly not caused by deficits, which became much larger after 1981, precisely when the Great Inflation ended. It was caused by printing money and buying bonds with the newly-issued money.

Mike: This episode is consistent with both the quantity theory and the backing theory. The quantity theory says that inflation happened because money outran the production of goods by about 8%/year, while the backing theory says that inflation happened because money outran the Fed’s assets by 8%/year. Of course, measuring “the Fed’s assets” becomes much more confusing when we realize that the Federal Government might someday bail out the Fed, or loot the Fed, or force the Fed to buy junk assets, etc.

Scott: No, that is not my view. The Fed might well increase the money supply even if the real demand for money did not rise. There is always some price of bonds at which the Fed can induce people to exchange bonds for cash, even if they do not want to hold larger real cash balances. They’ll spend the new cash almost immediately after being paid for the bonds.

Mike: We are probably misunderstanding each other here. What I meant to say was that IF we see the money supply rising, with no corresponding rise in inflation, then I would explain it by saying that the Fed’s assets must have risen in step with the increased money supply, while Scott would explain it by saying that money demand must have risen in step with money supply.

Lastly, we have Scott’s replies to my 4 objections to the quantity theory:

(i) The rival money problem.

Scott: We occasionally do observe rival monies taking hold during extreme hyperinflation. The mystery is why doesn’t it happen with other inflation episodes. Fiat currencies have survived some pretty high rates of trend inflation, especially in Latin America. My best guess is the answer is “network effects.” There are huge efficiency gains from using a single currency in a given region. It’s hard to dislodge the incumbent.

Mike: It’s easy to use US dollars in Canadian border towns, and even easier to use it throughout Mexico. Network effects look pretty weak in this case. If you’re a quantity theorist, the survival of the peso is a “mystery”, and requires you to make a “best guess”. The backing theory requires no such logical contortions. The backing theory gives the straightforward answer that the peso retains value because the peso is backed.

(ii) The counterfeiter problem.

Scott: When I teach monetary economics I ask my students to think of the Fed as a counterfeiter. I say that’s the best way to understand monetary economics. And there is some ambiguity to the “stands ready” in the final line of the quotation. Was that true during the Great Inflation?

Mike: Once again the quantity theory leads us into a logical contortion, saying that the Fed can be thought of as a counterfeiter even though it is obviously not a counterfeiter. Where is the counterfeiter who puts his name on his money, recognizes that money as his liability, holds assets against that money, and stands ready to use his assets to buy back its money? There is no such person.

About “standing ready”: Under the Fed’s 1950’s policy of targeting free reserves, the Fed would monitor the levels of vault cash held by private banks. If the level got dangerously low, the fed would buy bonds, and vault cash would be replenished. If vault cash became excessive, the Fed used its bonds to buy back that cash, thus soaking up unwanted cash. That’s what I mean by standing ready. But if the Fed allowed unwanted cash to pile up without buying it back, then the Fed would effectively be defaulting on its promise to stand ready, That is tantamount to a partial loss of backing, and would cause inflation.

(iii) The currency buy-back problem.

Scott: There are two ways to address this. One possibility is that the central bank does not reduce the base when needed to hit a particular inflation target. That describes the 1960s and 1970s. But what about when they are successfully targeting inflation at 2%? In that case they’d need some assets to do open market sales, but they might well get by with far less than 100% backing. The last point (about a 100% fall in money demand) feeds into his final objection:

“less than 100% backing” leads to yet another logical contortion. A bank with less than 100% assets is an insolvent bank, and it will not survive. Has any bank ever survived with (say) 30% reserves? I don’t know of any.

(iv) The last period problem.

Scott: There are two possibilities here. One is that the public never believes the world will end with certainty, rather that each year there is a 1/1000 chance of the world ending. In that case people would still hold cash as long as the liquidity benefits exceeded 0.10% (10 basis points), which seems quite plausible given the fact that people still hold substantial quantities of cash when inflation reaches double digits.

Now let’s consider a case with a definite end of the road, say the German mark or French franc in 2001. In that case the public would expect redemption for an alternative asset with a relatively similar real value (euros in the case.) I’m actually not sure whether it matters if the central bank holds the assets used for redemption, rather than some other institution like the Treasury. But yes, they would expect some sort of backing in that case. But even so, OMPs will still be inflationary, which contradicts the claims made by backing proponents.

Mike: I have to give Scott credit for giving a good answer to this, but his answer is still far more complicated than the backing theory answer, which is that money has value, from this period to the last period, because it is backed. The simplest theory is probably the correct one.

Scott: One final point. We all agree that gold need not be “backed” to have value. The QTM implicitly thinks of cash as a sort of paper gold. It’s a real asset that has value because it provides liquidity services. As an analogy, gasoline makes cars go. Motor oil doesn’t propel a car forward. But motor oil has value because it lubricates engine parts. It’s harder to model the value of motor oil than gasoline, because the advantages are less obvious. Similarly, it’s harder to model the value of cash than gold or houses or stocks. But cash lubricates transactions, and hence a medium of exchange has value. But once you have that monetary system in place, having twice as much cash adds no extra value. Instead all prices double, and the value of cash falls in half. It’s the monetary system that has real value.

Mike: It’s a big jump to go from gold, which is an actual commodity and nobody’s liability, to bank notes, which are not a commodity and are the liability of the issuer. But for the sake of argument, grant that paper might have value even with no backing. If people have a choice of using that money or some other money that does have backing, they should and would choose the one with backing. The backed money does the same lubrication and generates the same value, but without the eyebrow-raising problem of having no assets backing it.

6. June 2014 at 05:31

Tom, I haven’t read it.

Jason. It seems like currency reforms show it must be P = kM

Mike, You said:

“In the case of the US dollar, the physical assets include the Fed’s gold and office buildings, in addition to the US government’s ability to take physical property from us through taxation.”

I don’t follow this at all. Dollars are no longer redeemable into gold at any fixed rate. So while the Fed holds some gold, that plays no role in pinning down the purchasing power of cash. That’s why the purchasing power of cash has plunged 94% in the past 100 years; the gold backing no longer means anything. The market price of gold has soared. Oddly, I seem to recall criticizing a Tyler Cowen (and Kroszner) paper on the same grounds back in 1991 or so (JMCB.)

You said;

“Of course, measuring “the Fed’s assets” becomes much more confusing when we realize that the Federal Government might someday bail out the Fed, or loot the Fed, or force the Fed to buy junk assets, etc.”

Isn’t that a pragmatic reason to support the QTM?

You said;

“The backing theory gives the straightforward answer that the peso retains value because the peso is backed.”

Actually I don’t think that helps. It still doesn’t explain why people would choose to hold pesos depreciating at say 10% per year rather than US dollars depreciating at say 2% per year. (Not the current US/Mexico inflation differential, but one that has persisted in the past in Latin America.)

On the counterfeiting example, I assured my students that what the Fed does is legal, and hence they do not need to hide their actions like an actual counterfeiter would. But the macroeconomic effects are the same as if I printed $100 bills and went to the bank and bought back my mortgage with the newly printed money.

I agree that vault cash is freely convertible into bank reserves, and hence the components of the base are endogenous. But the overall base can be considered exogenous in the long run (of course over any 6 weeks its endogenous as well due to the interest rate peg.)

Regarding the 30% backing, that would work as long as base demand never fell by more than 30%.

Regarding your last point, I think it’s important to note that fiat currencies evolved out of commodity-backed currencies. The long history of commodity backing conditioned Americans to think of currency as a “real asset” which made it easier for the Treasury to withdraw gold backing. Here’s a thought experiment I like. Suppose 500 people wash up on a deserted island and start a new society. A crate of Monopoly games also washes up in the wreckage. I think it’s quite possible that the new society divvies up the Monopoly money equally and adopts a “social convention” that it will be used as a medium of exchange. Even if unbacked. It looks more like “money” than sea shells do. Obviously I can’t prove that, but given what I know about human behavior I find it plausible that this would occur. If it did occur, I predict that the NGDP would end up being somewhere in the neighborhood of 10 to 25 times the money stock. Closer to 10 if people also used Monopoly money as a store of value.

I agree that my hybrid theory for the US (first backed then unbacked) is less unified than your theory, but I see lots of evidence that base money is neutral under a fiat money regime, which is why I lean to the more complicated theory. On the other hand I tend to define “money” differently than others, as the medium of account, not the medium of exchange. In that case my theory is also unified–it’s all about the supply and demand for the medium of account (first gold, more recently cash.)

6. June 2014 at 06:02

Mike Sproul:

“If people have a choice of using that money or some other money that does have backing, they should and would choose the one with backing.”

If that’s the case, why do some orphaned currencies retain value even without any kind of backing? Somali Shillings did not suffer in value when the issuing central bank was looted and thus all backing assets were lost. Similarly Iraqi “Swiss” Dinars retained their value even after their issuer announced their demonetization. These cases have been discussed on the very same blog you posted to:

http://jpkoning.blogspot.ca/2013/03/orphaned-currency-odd-case-of-somali.html

http://jpkoning.blogspot.fi/2013/05/disowned-currency-odd-case-of-iraqi.html

Also, why does Bitcoin appear to have market value without any kind of backing? If hypothetically the users would agree to chance the Bitcoin protocol, such that the currency stock increased significantly, would it’s value be unaffected because the (zero) backing assets remained unchanged?

6. June 2014 at 08:00

Scott (and Ossi)

Scott said: “Dollars are no longer redeemable into gold at any fixed rate. So while the Fed holds some gold, that plays no role in pinning down the purchasing power of cash.”

If gold convertibility were suspended for a weekend, then people would still value the dollars because the gold is still there in the vault, and they expect gold convertibility to be resumed on Monday. The same is true if the suspension lasts 30 days, 30 years, or for an unspecified period. The public cares about two things:

1. The gold is still there in the vault

2. If you no longer want your paper dollar, you can redeem it at the Fed (or the Treasury) for debt relief, a bond, or tax relief. As long as those redemption channels are open, people don’t care if the gold channel is closed, especially if they expect it to re-open in 100 years.

Scott said: “Isn’t that a pragmatic reason to support the QTM?”

It’s also a pragmatic reason to support the backing theory. The QT says that inflation happens when “money” (=FRN’s? or M1? Or M2? Or God knows what?) outruns “real output” (Which also =God knows what) The BT says inflation happens when FRN’s outrun the Fed’s assets (=God knows what). The “God knows” variable appears less in the BT than in the QT.

Scott said: “Actually I don’t think that helps. It still doesn’t explain why people would choose to hold pesos depreciating at say 10% per year rather than US dollars depreciating at say 2% per year. (Not the current US/Mexico inflation differential, but one that has persisted in the past in Latin America.)”

I’m not sure why you think I have to explain that. If I carry $100 in my wallet at any given time, then I sacrifice $2/year in exchange for all that liquidity. So what?

Scott said: “On the counterfeiting example, I assured my students that what the Fed does is legal, and hence they do not need to hide their actions like an actual counterfeiter would. But the macroeconomic effects are the same as if I printed $100 bills and went to the bank and bought back my mortgage with the newly printed money.”

Beside the point, which is that the QT leads us to a comparison (Fed=counterfeiter) that is clearly false, while the BT does not.

Scott said: “Regarding the 30% backing, that would work as long as base demand never fell by more than 30%.”

And it would fail as soon as base demand fell by 31%. Speculators know this, so you’d see a Thailand-style run on the bank, and the George Soros’ of the world would walk away with the central bank’s assets.

Scott said: “Here’s a thought experiment I like. Suppose 500 people wash up on a deserted island and start a new society. A crate of Monopoly games also washes up in the wreckage. I think it’s quite possible that the new society divvies up the Monopoly money equally and adopts a “social convention” that it will be used as a medium of exchange. Even if unbacked. It looks more like “money” than sea shells do. Obviously I can’t prove that, but given what I know about human behavior I find it plausible that this would occur. ”

I’ll prove it for you. I think I first saw this story on the back cover of the JPE in the 1980’s. Some sailors in WWII bought stuff from islanders using Monopoly money, which looked real to the natives. Some of the sailors came back to the island years later and found the Monopoly money still circulating.

Stories like that have a common theme. People start with something rare (gold, shells, bits of printed paper, bitcoins), and they value it as a curiosity. Once it has value, they trade with it, and as it becomes widely used as money, the demand for it increases and its value rises higher. You’d say that this validates the QT, and I’d say that it validates the law of supply and demand. But it certainly doesn’t invalidate the BT. Look at the actual moneys used in 99.99% of trades. Those moneys do not resemble those ‘curiosity’ moneys. They resemble stocks and bonds, in that they are the liability of the issuer, and are backed by the issuer’s assets.

6. June 2014 at 14:20

Mike Sproul

In your post you state that if the Fed would increase the base 10-fold such that the newly issued dollars were exchanged for assets of equal value, there would be no additional inflation. I find this a bit hard to understand.

Consider two hypothetical world where in world-A Fed increases the base 10-fold (acquiring assets at issuance) and world-B there’s no 10-fold increase (business as usual). Up to the point where this takes or doesn’t take place the worlds are identical. You predict that the rates of inflation would not differ (much) in these two worlds. This means, by definition, that demand for money is higher in world-A (due to more backing assets?). Why would the public in world-A be willing to hold 10 times higher amount of cash relative to income?

In your post you talk about money only being issued in response to increase in money demand. But clearly the Fed is able to issue new base money in exchange for assets regardless of whether money demand changes or not. In fact, your theory would seem to predict that money demand would change in response to the issuance and acquiring of assets. I find that rather hard to believe.

6. June 2014 at 17:24

Ossi:

I haven’t mentioned the Law of Reflux (LOR) on this thread, but it’s crucial. Basically it says that unwanted money will reflux to its issuer, so the only way you’d get that 10x increase in money is if people wanted that money badly enough to hand over their high-interest-earning bonds in exchange for some low (or zero) interest-bearing money. Naturally, if the Fed started paying $101 for bonds worth only $100, then the public would bring all the bonds they have to the Fed and the money supply would explode, but of course if the Fed did that, they would be getting inadequate backing for the new dollars, and the backing theory says there would be inflation.

Here’s a simple example of the LOR: A Mint stamps 1 oz of silver into 1 oz coins (“dollars”). They do this on demand whenever people bring in 1 oz of silver. What if the Mint suddenly minted 10x as many coins? Answer: People would melt them, and the coins would reflux to bullion. No matter how much minting is done, $1=1 oz, and it’s not because the LOR limits the quantity of coins, it’s because the mint follows the backing theory by only issuing a coin to people who bring in 1 oz. In other words, the mint obeys the RBD. I should add that a rational mint would never issue 10x as many coins in the first place.

Next, to save work and trouble, the mint starts offering to issue a paper receipt (a paper dollar) to anyone who brings in 1 oz. Everyone likes this. The paper dollar is easier to produce, easier to trade with, and still backed by 1 oz of silver held in the mint’s vault. The LOR still works the same way. If the mint produces 10x more paper dollars, people will return them to the bank (mint) and take out the silver.

Next, the bank starts a new policy where people can bring in either 1 oz, or else other stuff (deeds, bonds, etc) that is worth 1 oz. The bank issues a paper dollar just the same, but now the bank reserves the right to redeem the paper dollars not just for silver, but for the deeds and bonds as well. This is reasonable, since the dollars were issued for deeds and bonds in the first place. Once again, the LOR works the same. The bank could even suspend silver convertibility for 100 years, and people might not even notice.

Except that Scott would then deny that the paper dollars were the liability of the mint.

6. June 2014 at 20:40

Thanks for sharing Scott, interesting post.

(iv) The last period problem.

That’s amusing. Very few people expect to cash in their cash for something more concrete to be used a medium of exchange in any kind of planning horizon — and those people are mainly stocking up on lead and cordite.

Heck, you might just as well argue that at some future point your gold will be worthless as the Sun expands and 10^100 or so years later the universe expires.

7. June 2014 at 01:14

I like backing models when they are properly done. You need to recognize intangible assets as a backing source (bitcoin is a good proof why you need to do this). You also have to understand that not all assets are available for backing, as you need to recognize future seignorage on the other side of CB balance sheet too.

7. June 2014 at 06:09

Scott, you write:

“Jason. It seems like currency reforms show it must be P = kM”

I *think* I’d brought up a similar point to Jason in the past:

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2013/09/the-liquidity-trap-and-information-trap.html?showComment=1399155216895#c356072464206390852

Tom:

“Here’s what I don’t get: suppose by presidential decree, the penny were made the new UoA tomorrow: The decimal place on all debts, contracts (including wager contracts), and prices just shift two places to the right, but otherwise nothing else changes. I don’t see how that affects anything, but on your chart couldn’t that shove a country from non-information trap status to information trap status?”

Jason:

“…such a change would change not only the quantities like NGDP and MB, but the dimensionful coefficients in the model (which have units of dollars). The result would be no change.”

7. June 2014 at 06:45

Mike You said:

“Beside the point, which is that the QT leads us to a comparison (Fed=counterfeiter) that is clearly false, while the BT does not.”

I don’t accept that. The QTM does not say counterfeit money and Fed money are alike in all ways. One is legal and one is illegal, to give one obvious counterexample. It says they are alike in creating something from nothing, and in creating inflation.

You said:

“I’m not sure why you think I have to explain that. If I carry $100 in my wallet at any given time, then I sacrifice $2/year in exchange for all that liquidity. So what?”

I was responding to your claim that a backed currency would displace an unbacked currency. My counterexample was that a currency with a low op. cost doesn’t necessarily replace a currency with a high op. cost of holding it. Better doesn’t always displace “worse.”

One final point, I don’t really agree with your claim that there is a lot of observational equivalence here. We had lots and lots of studies of money demand, and the empirical results of these studies seems to conflict with backing theory. Think about the demand for currency as a share of GDP (for simplicity, assume the entire base is currency, with bank reserve being vault cash. Assume nominal interest rates are positive.) Now assume the Fed doubles the base. The new money is fully backed by bonds. I say the bonds would be purchased at pretty close to existing market prices (the base is far smaller than the stock of bonds), and the price level roughly doubles. I believe the backing theory predicts little change in the price level and NGDP. In other words the backing theory says the Fed’s action causes people to want to hold currency stocks at roughly twice the share of GDP than before the OMO, if the currency is backed. Is that right? I say that view conflicts with money demand studies. The new currency would be a hot potato. And if the public tries to take this unwanted currency back to the Fed, the Fed won’t take it back. They’ll say “tough luck, you’ll just have to live with the inflation.” Indeed to me that describes the Great Inflation.

After I wrote this I see that Ossi asked a similar question. So does that mean that you do think actual real world OMPs are inflationary? Wouldn’t the Fed always pay epsilon more than the going market price to add to their stock of bonds? And in Ossi’s example would you agree that if the purchase of bonds caused bond prices to go up 1%, and the stock of base money rose 1000%, then the price level would rise by 1000%? Maybe we aren’t as far apart as I assumed.

One final point, assume that the new money is 100% fully backed, as the Treasury “gives” the Fed any extra bonds needed to offset overpaying in OMOs. In that case we still have the big currency stock increase. Why does the public want to hold all that extra non-interest bearing currency, if there is no price level rise?

Talldave, Good analogy with gold and the sun.

Tom, But what if the currency reform kept dollars as the MOA. Each person got $100 dollars for each dollar they already had? That would be easy to do in a world of electronic money.

7. June 2014 at 09:24

Scott, you said “It seems like currency reforms show it must be P = kM”

Wouldn’t the results of currency reforms only show that any model of the price level just has to be scale invariant with respect to the unit of account? P = k (M/M0) and log P = k log(M/M0) both fit that bill.

When Tom brought up the same point above (thanks, Tom!); you responded:

“Tom, But what if the currency reform kept dollars as the MOA. Each person got $100 dollars for each dollar they already had? That would be easy to do in a world of electronic money.”

Has there ever been a currency reform where this has happened? It seems like this kind of reform would be not just inflationary, but hyper-inflationary.

The best evidence in favor of log P ~ k log M is empirical. Here is a fit to log P = k log (M/M0) with k = 0.61 and M0 = 106 M$

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=CNT

And here is the best fit to P = k (M/M0) with M0/k = 1561 M$

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=CNV

The former fit is much better than the latter. In the case of currency reform where $100 is given out for every $1, then maybe that just means k = 1 so that log P ~ k log M becomes P ~ M.

I’d say the scenario where we use log P ~ k log M over long periods (and reduces to P ~ M over short periods) and take k = 1 during currency reforms is preferable to the scenario where we use P = k M even though it doesn’t work for the US over the post-war period, but it works for currency reforms.

7. June 2014 at 10:16

Scott:

Scott said: “The QTM does not say counterfeit money and Fed money are alike in all ways. One is legal and one is illegal, to give one obvious counterexample. It says they are alike in creating something from nothing, and in creating inflation.”

The QT says the Fed is like a counterfeiter. Not exactly alike, but close. The BT says the Fed is not a counterfeiter, and it clearly isn’t. Debate etiquette normally gives the edge to the simplest explanation, and the BT is clearly simpler than the QT in this case.

Scott said: “I was responding to your claim that a backed currency would displace an unbacked currency. My counterexample was that a currency with a low op. cost doesn’t necessarily replace a currency with a high op. cost of holding it.”

I’ll rephrase: Other Things Equal, people will hold backed money in preference to unbacked money.

Scott said: “We had lots and lots of studies of money demand, and the empirical results of these studies seems to conflict with backing theory.”

In the vast majority of the empirical studies supporting the QT, there is no mention of the BT or the RBD. They weren’t trying to test the QT vs. the BT. They were testing the QT against various stripes of Keynesian theories or whatever. The few empirical studies that directly compared the QT and the BT (Smith, Siklos, Calomiris, Sargent, Bomberger and Makinen, etc) mostly favored the BT over the QT.

Of course, the older I get, more I disregard empirical studies, since it’s so easy for researchers to only look at the data they want to see, while ignoring the rest.

Scott said: “in Ossi’s example would you agree that if the purchase of bonds caused bond prices to go up 1%, and the stock of base money rose 1000%, then the price level would rise by 1000%?”

Wow. That just doesn’t compute with the backing theory. The best answer I can give is the explanation of the Law of Reflux that I gave above in my answer to Ossi. You can’t just go around assuming a 10x increase in the money supply.

Scott said: “Why does the public want to hold all that extra non-interest bearing currency, if there is no price level rise?”

I have three answers to that: (1) Law of Reflux, (2) Law of Reflux, (3) Law of Reflux.

8. June 2014 at 05:27

Jason, We may be confusing two issues. I’m not saying money and prices will grow at the same rate. I’m saying prices will grow proportionally to an exogenous change in M.

Mike, You said:

“The QT says the Fed is like a counterfeiter. Not exactly alike, but close. The BT says the Fed is not a counterfeiter, and it clearly isn’t.”

There is no conflict here. Not exactly alike means clearly different. Both are true. The differences NOT predicted by the QTM, are far from “clear” otherwise I would believe them.

You said:

“Debate etiquette normally gives the edge to the simplest explanation, and the BT is clearly simpler than the QT in this case.”

I don’t see why it is simpler. What’s more simple than saying one is legal and one is illegal?

You said:

I’ll rephrase: Other Things Equal, people will hold backed money in preference to unbacked money.”

In that case I don’t follow your example of one currency displacing another over the border. Other things are not equal in that case. So why would the displacement necessarily occur?

I don’t agree with the law of reflux under fiat money. The Fed can “force” money into the economy with an open market purchase. They do this all the time. If you walk up to the Fed with your $20 bill and say you want it redeemed, they will refuse. That creates the hot potato effect and the inflation. That created the Great Inflation.

Again, assume the Fed does lots of OMOs, making the base rise 10 fold when interest rates are positive. Then assume any tiny losses in the value of the Fed’s bonds are offset by gifts from the Treasury. In that case the price level will rise in proportion to the rise in the money supply, which would be an enormous amount. To apply the backing theory to that case would require you to argue that a tiny loss in the value of bonds could cause a huge rise in the price level.

8. June 2014 at 11:28

“The Bank of Canada has been paying interest on reserves for 20 years. And when it wants to increase the inflation rate, because it fears inflation will fall below the 2% target if it does nothing, the Bank of Canada lowers the interest rate on reserves. And the Bank of Canada seems to have gotten the sign right, because it has hit the 2% inflation target on average, which would be an amazing fluke it if had been turning the steering wheel the wrong way for the last 20 years without going off in totally the wrong direction.”

Until 2008, currency and central bank reserves paid 0% in the USA.

What was the fed doing?

8. June 2014 at 11:34

“I don’t agree with the law of reflux under fiat money. The Fed can “force” money into the economy with an open market purchase. They do this all the time. If you walk up to the Fed with your $20 bill and say you want it redeemed, they will refuse. That creates the hot potato effect and the inflation. That created the Great Inflation.”

That is not how the system works.

Someone takes $20 in currency to a commercial bank for exchange. The commercial bank takes the $20 in currency to the fed for exchange. It gets central bank reserves. It may exchange the central bank reserves for assets at the central bank (usually gov’t bonds).

The way the system is set up now, currency can always reflux back to the fed. The central bank reserves may not reflux depending on what the fed is doing.

8. June 2014 at 13:33

Fed up, You asked:

What was the fed doing?

Taylor rule.

Regarding currency, if you look at the earlier exchange I was using currency to refer to the monetary base.

8. June 2014 at 19:46

Doesn’t the Taylor rule apply to the fed funds rate, not interest on reserves?

I definitely believe you should not use currency to mean monetary base.

There is currency, central bank reserves (or whatever name), and demand deposits. Those are all different.

9. June 2014 at 05:01

Fed up, You are discussing something I said in a comment thread, you need to go back and understand the context. I was trying to simplify the discussion of the backing theory. In that context the currency/reserves distinction doesn’t matter.

And yes, the Taylor Rule applies to the fed funds rate. I don’t recall saying it applies to IOR.

9. June 2014 at 06:09

“2. If you no longer want your paper dollar, you can redeem it at the Fed (or the Treasury) for debt relief, a bond, or tax relief. As long as those redemption channels are open, people don’t care if the gold channel is closed, especially if they expect it to re-open in 100 years.”

Total explanation fail. No one expects the gold channel to re-open ever.

“Beside the point, which is that the QT leads us to a comparison (Fed=counterfeiter) that is clearly false”

It is an analogy, and analogies are always somewhat true and somewhat false. That should not be an equal sign in parentheses there, but a “somewhat similar to” sign.

9. June 2014 at 11:34

Scott, you said: “I’m not saying money and prices will grow at the same rate. I’m saying prices will grow proportionally to an exogenous change in M.”

I think that means you are saying log P = k log M.

If P = k M and P ~ exp(i t) and M ~ exp(r t), then dP/dt = k dM/dt becomes i P = k r M. Dividing by the initial equation P = k M, we get i = r therefore the rate of increase must be the same.

If log P = k log M, then we have i*t = k r*t. Taking the time derivative, we get i = k*r so the rate of increase is different, but an increase in M means an increase in P and a larger increase in P means a larger increase in M (proportional increase with exogenous change in M).

This latter equation is also more consistent with long run neutrality of money. Bennett McCallum [1] said that the quantity theory is defined by long run neutrality which implies that the supply and demand functions are homogenous of degree zero. The simplest homogenous diff.eq. for the rate of change of P with respect to exogenous changes in M is:

dP/dM = k P/M

This means that P ~ M^(k) or log P = k log M. It is that diff.eq. that says prices will grow proportionally to an exogenous change in M, but not necessarily at the same rate.

[1] Long-Run Monetary Neutrality and Contemporary Policy Analysis Bennett T. McCallum (2004)

Another explanation from a different perspective is here:

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2014/02/i-quantity-theory-and-effective-field.html

[sorry for the long comment]

9. June 2014 at 15:50

“Fed up, You are discussing something I said in a comment thread, you need to go back and understand the context. I was trying to simplify the discussion of the backing theory. In that context the currency/reserves distinction doesn’t matter.”

I’ll keep that in mind, but the distinction can matter because it brings up the issue of whether for every demand deposit there is a central bank reserve.

“And yes, the Taylor Rule applies to the fed funds rate. I don’t recall saying it applies to IOR.”

Nick’s post said: “The Bank of Canada has been paying interest on reserves for 20 years. And when it wants to increase the inflation rate, because it fears inflation will fall below the 2% target if it does nothing, the Bank of Canada lowers the interest rate on reserves. And the Bank of Canada seems to have gotten the sign right, because it has hit the 2% inflation target on average, which would be an amazing fluke it if had been turning the steering wheel the wrong way for the last 20 years without going off in totally the wrong direction.”

Nick gives the impression that the IOR rate matters. I pointed out that currency and the IOR rate in the USA were both zero until around 2008. I asked what was the fed doing.

The point is whether the fed funds rate (or foreign equivalent) is the rate that matters.

Another way asking it is did the Canadian “fed funds rate” (whatever name it is) also go down.

9. June 2014 at 20:25

brilliant.

money isn’t the oil, or even the car. its the whole road network…allowing people to get where they need to go.

who are these backer freaks – exactly as you point out, whats so special about gold? at the time with miniscule growth it worked ok, a good property then was that it was hard to counterfeit…its problem now is gold would be massively deflationary…bring on the NGDP markets…

they must be some sort of intrinsic value cranks =)

10. June 2014 at 06:11

Jason, Perhaps we are talking past each other. I’m not comfortable with any claim about the correlation between M and P, as it depends on the changes in other variables like V and Y. If you are arguing that M and P don’t tend to increase at the same rate in the real world, then I agree. But that has no bearing on the neutrality of money, which refers to exogenous changes in M, as you indicated.

I may have misunderstood your previous comment.

Fed up, Yes, I’m sure the Canadian fed funds rate (or its equivalent) moved closely with the IOR rate.

10. June 2014 at 08:59

Start at IOR = 0% and fed funds rate = 8%.

Next, move to IOR = 2% and fed funds rate = 6%.

What happens?

10. June 2014 at 18:51

Gene:

“Total explanation fail. No one expects the gold channel to re-open ever.”

Do you think the Fed might sell some of its gold in the next 100 years? That’s a re-opening of the gold channel. The old Bank of Amsterdam always maintained gold convertibility, but its customers would go for centuries without redeeming. If they had suspended gold convertibility people wouldn’t have cared. All that mattered was that the gold was there in the vault.

Fed Up:

“The way the system is set up now, currency can always reflux back to the fed. The central bank reserves may not reflux depending on what the fed is doing.”

Good point.

Scott said: “ I don’t see why it is simpler. What’s more simple than saying one is legal and one is illegal?”

Do we care what’s legal? If we do, I know plenty of people who think the Fed is unconstitutional. But if we focus on comparing the economics of the BT vs QT, the fact that the QT implies that the Fed is “sort of” equal to a counterfeiter, is a point against the QT.

Scott said:” The Fed can “force” money into the economy with an open market purchase. They do this all the time. If you walk up to the Fed with your $20 bill and say you want it redeemed, they will refuse. That creates the hot potato effect and the inflation. That created the Great Inflation.”

Nowadays, as Fed up observed, all the Fed can do is force private banks to hold more Fed funds. Just bookkeeping entries piling up in private vaults. But grant your position and suppose the Fed overpays for bonds (or undercharges for loans) and puts 10x more paper FRN’s into private hands, and at the same time closes all reflux channels. That closing of reflux channels is an effective default by the Fed, which means there are effectively fewer assets backing each dollar, and the BT could yield 10x inflation. It’s just that the BT says the inflation happened because there is less backing per dollar, where the QT would have said inflation happened because there was 10x as many dollars chasing the same goods.

Scott: You didn’t respond to my statement that the empirical studies hardly ever compared the QT to the BT, and the few that did favored the BT.

11. June 2014 at 04:58

Fedup, I’ll do a post on that.

Mike, Fed up’s point was not a “good point” as he was confused about our discussion. I was using the term ‘currency’ to represent all of the monetary base. And you cannot return base money to the Fed. As Fed up said, currency gets turned into bank reserves–no reflux of base money.

The reason I didn’t discuss the empirical studies is that I’m not an expert in that area. The only ones I recall reading had to do with Colonial currency injections, and I once published a paper arguing they misinterpreted the QTM. So those particular studies weren’t a useful test.

The bigger problem is that I still don’t understand the backing theory. I had originally though the backing theory went as follows:

1. Helicopter drops are inflationary, because the new cash is not backed.

2. OMPs are not inflationary, because the new cash is backed by an equivalent amount of government bonds.

I would know how to test that theory. But here you suggest that:

“Nowadays, as Fed up observed, all the Fed can do is force private banks to hold more Fed funds. Just bookkeeping entries piling up in private vaults. But grant your position and suppose the Fed overpays for bonds (or undercharges for loans) and puts 10x more paper FRN’s into private hands, and at the same time closes all reflux channels. That closing of reflux channels is an effective default by the Fed, which means there are effectively fewer assets backing each dollar, and the BT could yield 10x inflation. It’s just that the BT says the inflation happened because there is less backing per dollar, where the QT would have said inflation happened because there was 10x as many dollars chasing the same goods.”

This makes no sense to me. The drop in backing is trivial, as the OMPs have only a small effect on bond prices. This case is still much more like case #2 than case #1. And as I said, we could have the Treasury give the Fed a few extra bonds if necessary to assure 100% “backing.” My claim is that you’d still get inflation. Or if you don’t like the gift idea, simply assume the Fed keeps enough seignorage to assure 100% backing. I still say that prices rise 10-fold, for neutrality of money reasons.

Regarding counterfeiting, it doesn’t matter if some people believe the Fed is illegal. The reason illegality matters for counterfeiters is that they fear arrest and imprisonment. Their behavior differs from central banks for that reason.

11. June 2014 at 06:12

Scott said: “This makes no sense to me. The drop in backing is trivial, as the OMPs have only a small effect on bond prices.”

Example: The fed has issued $100 of FRN’s and its assets consist of 10 oz of gold, plus bonds worth 90 oz, so on BT principles, $1=1 oz. Then the fed issues another $900 of FRN’s and uses them to buy 899 oz. worth of bonds (or $899 worth, denomination wouldn’t matter). Assuming there had been no change in the public’s demand for cash, the $900 of FRN’s can be called “forced”. But that $900 would want to reflux to the Fed. If the Fed left ANY channel of reflux open, then they would reflux, and the money supply would drop back to $100 no matter how many bonds the Fed bought.

So to make the thought experiment work, we must assume that the fed closes all reflux channels, thus forcing the $900 to remain in circulation. The key point, and the reason that my previous comment made no sense to you, is that the closing of reflux channels is tantamount to a default by the Fed. It is as if the fed had lost 900 oz worth of assets. They didn’t really lose it, but the fed’s refusal to maintain even one kind convertibility would have the same effect as if the 900 oz had been lost.

So in this case, the BT and the QT look a lot alike. The BT says that the forcing of $900 (along with closing of reflux channels) would cause 10x inflation because there is less actual backing per dollar. The QT would say that the forcing of $900 (and closing of reflux channels) caused inflation because there are 10x more dollars chasing the same goods.

11. June 2014 at 17:30

Mike, OK, so I had misunderstood backing theory. There is currently no reflux channel. That means open market purchases are inflationary under both theories. I had thought the backing theory denied that OMPs were inflationary under the current policy regime, as long as the Fed held bonds of equivalent value.

11. June 2014 at 19:01

Scott:

What a relief! The clarification of that one misunderstanding was well-worth the effort!

12. June 2014 at 05:52

Mike, As I reread your earlier comments, this is probably what confused me:

“Mike: This episode is consistent with both the quantity theory and the backing theory. The quantity theory says that inflation happened because money outran the production of goods by about 8%/year, while the backing theory says that inflation happened because money outran the Fed’s assets by 8%/year. Of course, measuring “the Fed’s assets” becomes much more confusing when we realize that the Federal Government might someday bail out the Fed, or loot the Fed, or force the Fed to buy junk assets, etc.”

I presume I underestimated the “confusing” comment, and focused too much on the mere fact that the Fed buys bonds when M rises.

12. June 2014 at 09:51

“Mike, Fed up’s point was not a “good point” as he was confused about our discussion. I was using the term ‘currency’ to represent all of the monetary base. And you cannot return base money to the Fed. As Fed up said, currency gets turned into bank reserves-no reflux of base money.”

If you use the term “currency” to represent all of the monetary base, I doubt if I will be the one considered confused.

I would not use the phrase cannot return central bank reserves to the fed. It depends on what the fed is doing. They may return or may not return. I do not see why it is not possible for everyone to turn in their currency to the commercial banks. The commercial banks then turn the currency into the fed for central bank reserves. The fed funds rate could start falling below target. The fed buys back all the central bank reserves. The monetary base (currency plus central bank reserves) could go to zero if the reserve requirement was 0% and the commercial banks did not want any central bank reserves.

12. June 2014 at 10:02

I disagree that open market purchases have to be price inflationary. They might be. They might not be.

Have the fed buy existing gov’t bonds from Apple with “new money”.

Central bank reserves go up at Apple’s bank. Demand deposits go up at Apple. Apple continues to save using the demand deposits as the asset instead of gov’t bonds. Nothing may happen, especially if interest rates (of the gov’t bonds and fed funds rate) stay near the same.

13. June 2014 at 05:33

Fed up, Sure that might happen, but it has no bearing on the specific discussion I was having with Mike.

You said:

“I disagree that open market purchases have to be price inflationary. They might be. They might not be.”

Disagree with whom? I never said they had to be inflationary. Something else might happen at the same time that offsets the effect.

16. June 2014 at 20:31

From above ssumner said: “I don’t agree. If the Fed doubles the monetary base by purchasing an equal amount of government debt at going market prices, the price level will double in the long run.”

What offsets?

16. June 2014 at 20:37

You and Mike S. were talking about reflux.

The way the system is set up now, currency can always reflux to the fed. The central bank reserves may or may not reflux depending on what the fed is doing.