British wages, prices, and NGDP

Karl Smith recently made the following offhand comment:

To give meat to the idea – its conventional wisdom to deny the existence of race. Scott Sumner has denied the existence of inflation. I assert the existence of both.

I agree about race, but have two problems with inflation. First, the term has never been clearly defined by economists. Is it the increase in nominal consumption that an American would need to maintain a constant flow of utility? If so, then we shouldn’t be using price indices to measure it. If happiness surveys show no rise in the reported happiness of Americans (on average) over the past 65 years, then inflation roughly equals median wage growth.

But I’m a philosophical pragmatist, happy to live with fuzzy concepts that are useful. The problem is that inflation isn’t even useful, as whenever people talk about inflation they are actually talking about something else.

1. Does inflation impose a tax on capital? No, rising nominal returns on capital impose a tax on capital. And those are caused by faster NGDP growth (and rising levels).

2. Are eurozone officials correct when they say inflation hurts consumers? No, supply shocks hurt consumers, and if the ECB prevents the supply shock from leading to inflation, consumers will be hurt EVEN MORE THAN IF PRICES DO RISE. The harm to consumers has NOTHING TO DO with prices rising.

3. Does inflation lead workers to demand higher wages? No, rising NGDP leads workers to demand higher wages.

If you are talking about inflation, you are talking about the wrong variable.

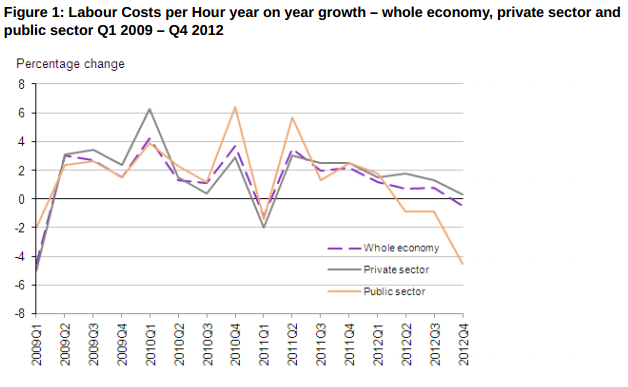

Britmouse sent me some data showing that nominal wage growth in the UK has fallen below zero by the end of 2012:

At the same time that wage growth has been slowing to zero, the BoE has been worried about high inflation–you know, the stuff that’s supposed to trigger high wage growth. Lars Christensen sent me the following:

U.K. inflation expectations risk becoming dislodged because consumer-price growth has been elevated for such a long time, Bank of England economists said.

“The prolonged period of above-target inflation could cause inflation expectations to become less well anchored,” the researchers wrote in an article in the central bank’s Quarterly Bulletin, published in London today. “That could trigger changes in the nominal exchange rate, and affect consumption and investment decisions, as well as wages and prices, and could cause inflation to persist above the target for longer.”

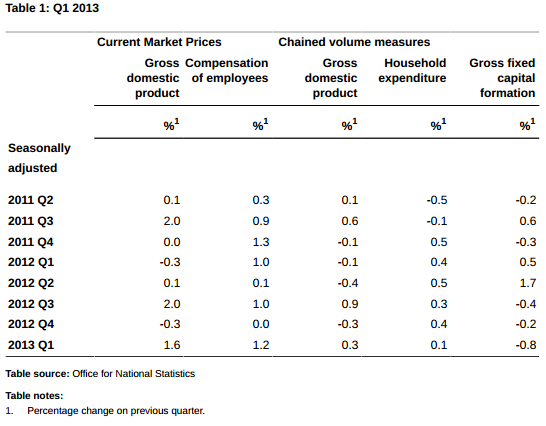

No, high inflation does not feed into high wage growth, as wages follow NGDP. British NGDP has been very weak; rising a total of 3.6% in the 7 quarters leading up to 2012:4, or 2% per annum:

Slow British NGDP growth has led to slow nominal wage growth. Indeed in one respect Britain is doing fairly well—employment has risen to record levels in recent months, unlike the US. What explains the difference? It appears that British wages are more flexible than US wages, which are still rising at about 2% per year.

Most people focus on British inflation and real GDP numbers. If these numbers are to be believed (and I have my doubts), all they tell us is that British productivity has fallen for some mysterious reason. British workers today are simply not as productive as British workers of 2007. The data tell us nothing about demand-side conditions in the economy. Inflation is a nearly worthless concept, and should be discarded from business cycle analysis. NGDP, hours worked, and wage inflation are the key concepts to focus on. The musical chairs model.

And Osborne is right:

Inflation has exceeded the BOE’s 2 percent target every month since December 2009, and Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne revamped its mandate in March to give it more flexibility to set policy.

I suspect that in private Osborne would agree with the analysis in this post, but holds back from NGDP targeting because of the innate conservatism of central banks and the financial establishment. Perhaps he also fears being bashed by Labour, and the Tory voters that are high savers. Maggie Thatcher got in hot water for saying there is no such thing as society. If I was advising Osborne I would recommend he NOT say; “Sumner’s right, there is no such thing as inflation.”

HT: Advisor to the British government

Tags:

15. June 2013 at 07:42

Osborne could point out that deflation risks “a Cyprus” and a loss of 60% of all deposits over £85k. Or, as recently rumoured for Italy and quickly denied, special taxes on deposits – presumably to recapitalise banks.

Banking as an industry cannot work in a deflationary environment as liabilities (deposits) stay nominal while repayment of assets (loans) are dependent on future income/cash flows of the borrowers, and these decline in a deflation. Balance sheets then no longer balance and equity holders, then debt capital holders, the depositors have to face hits.

15. June 2013 at 07:45

This is my problem: I think we’re running out of things to lever for debt.

The inflation discussion gets to the meat of it for me… if we give 300M Americans a free Harvard edu online $200K…

That’s $60T in consumption, and no one pays anything. GDP doesn’t grow.

Likewise, WHY don’t economists have a economic metric which works like this:

The first 60″ TV was $50K.

So if 100M households gain a 60″ TV, why is that not $5T in consumption value?

Why do we not AT LEAST measure this like this:

House

Car

Health – all out of patents scored at patent prices.

Computer Storage, Bandwidth, Processing

TV

Telecom- Skype + first mobile phones

Appliances – toaster in 1915 was $9.

Education

In broad categories, it is’t enough to just measure how many hours a man must work for X, we ought to also factor what the rich asshole first paid when the new shit first rolled off the line.

We don’t economist actually report on a nominal value of consumption that measures dispersed technology at its first retal cost?

Answer: That measure would make everyone A LOT richer and A LOT more even, and it dos’t empower / enrich economists to think that way.

15. June 2013 at 08:06

Morgan Warstler,

Suppose when the first toaster came out it was very expensive to make and could only be sold for $2000 (current dollars). Only one person had a low enough marginal utility of a dollar / high enough valuation of a toaster to buy such an expensive toaster. Today, since toaster prices have fallen significantly, many people are willing to buy them. Clearly, each person is not gaining $2000 (current dollars) of value. It would be a large overstatement of real growth to value a toaster at its initial price.

15. June 2013 at 09:38

“I’m a philosophical pragmatist, happy to live with fuzzy concepts . . . .” A good thing, because human thinking seems to be irremediably fuzzy. I’d worry that even our logical terminology falls short of perfect sharpness; there’s no chance that empirical terms, from economics, biology, sociology, or everyday life, attain that standard. ‘Race’ is certainly an example of fuzziness, but I suppose it passes the test of usefulness; after all, we still find uses even for the term ‘witch’.

But that example suggests that the usefulness test is not very demanding; I wonder if ‘inflation’ doesn’t pass it, after all. Of course, it would be better if people took the correct view of inflation, just as it is better that they take the correct view of witches (that there aren’t any), etc.

15. June 2013 at 09:55

Scott:

Inflation is a decrease in the purchasing power of money over goods and services.

Conceptually, it is defined for given relative prices of given goods and services.

We can consider scenarios where all the relative prices of all the goods and services remain the same, but the money prices rise or fall. Because relative prices remain unchanged and they are the prices of the same goods, all prices rise or fall in strict proportion.

When relative prices change, or some goods and services disappear and others are introduced, there is no unambiguous definition of the price level.

How much money it would take to keep utility constant? For everyone? I don’t think that is even a reasonable candidate.

If you go down the road of defining the price level in a way that makes it the best deflator to calculate real income such that real income measures the “true” standard of living, that is the direction you are heading.

And I grant that such seems to the goal of the BLS and BEA.

And I don’t think such efforts are worthless. Trying to figure out what is happening to standards of living is worthwhile.

On the other hand, I don’t think that is directly relevant to figuring out what is happening to the real quantity of money.

Suppose an ingot of steel is the medium of account. The price level is the relative price of steel (or its inverse.) It must adjust to clear the steel market.

Is the best measure of the relative price of steel take into account all the factors that might impact changes in the standard of living?

Would the flow of nominal income (or the nominal value of output) be a key determinant of the demand for steel?

I think the danger you see is that manipulating the quantity of money to control something designed to create a deflator that measures changes in standards of living is dangerous.

15. June 2013 at 11:14

Bill, I agree we can measure the price of a ton of flat rolled steel, but not much else. Almost everything else is changing in quality–so what exactly are we trying to measure in that case?

Everyone, I mostly agree with the comments.

15. June 2013 at 18:18

Scott,

Do you deny the existence of deflation?

15. June 2013 at 22:09

How would rising or relatively high NGDP growth act as a tax on capital if prices were steady or falling and growth was strong/growing? With strong real growth and steadily falling prices, it would be easy to accumulate capital by simply sticking it in a mattress, a bank account, or the most conservative of investments.

I don’t get why you say inflation hasn’t been well defined. You could define it as a generalized rise in prices or a fall in the purchasing power of money due to changes in supply and/or demand for money. I think the second method is more useful.

I think money itself is actually much tougher to define and more open to interpretation than inflation. See money as medium of exchange vs money as medium of account.

15. June 2013 at 22:26

Scott,

I don’t get why NGDP is better than real GDP or inflation. Any type of GDP includes government spending. GDP has the insoluble problem that government output is part of the economy but you can only measure economic value by market prices. It would be absurd to measure economic value by what businesses spend to create things but that’s how GDP treats government spending. The creators of national income accounting like Simon Kuznets rightfully agonized over how to treat government spending because it’s a totally different animal than private spending.

There are definitely problems with measuring inflation in terms of prices such as the change in qualities over time, the fact that each person has different consumption patterns and therefore experiences price changes differently, picking a consumption basket, it all boils down to the fact that aggregating price changes into an index is comparing apples and oranges. Much worse than that actually.

Defining inflation in terms of supply and demand for money has two simpler problems. What is money and how do you measure demand for money? I don’ think the second objection is a problem because economics is a logical discipline and not a purely empirical one. Even though you can’t measure demand for money in numbers it is a useful concept.

16. June 2013 at 05:26

J,

I want a measure from economists everyone sees and understands that measure the original retail price and adjusts for inflation, to describe the wealth of the bottom half according to what the rich first paid for first released items.

Also, we ought to measure / focus on Time Scale Inequality. Essentially, the most just society is the one that most quickly disperses shiny new inventions to the poor.

If we’re going to do stupid stuff like GINI Coefficient, we ought to be be measuring things that actually matter.

There will always be poor, relative wealth measured in money doesn’t most accurately describe what the poor live like.

16. June 2013 at 13:28

Morgan Warstler,

You completely ignored my comment. Adjusting for inflation does nothing to eliminate the issue I pointed out. The initial retail price is simply not relevant. Each person receives a different amount of utility from a given good or service. Some insanely expensive good only purchased by rich people may not be worth all that much to poor people (or other middle class and rich people that did not buy it at first) even if they eventually consume it as its price falls.

16. June 2013 at 13:34

Professor Sumner,

I believe there are a number of things wrong with this new piece on Wonk Blog:

http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/06/16/is-a-little-bit-of-inflation-just-what-the-doctor-ordered-to-keep-unemployment-down/

I particularly enjoyed this paragraph:

“That meant that employers who would be expected to have slashed jobs due to weak demand (remember, there was little to no economic growth in this period) instead kept employing people at lower rates. The weak demand translated into lower real wages rather than higher unemployment.”

He seems to believe that even if NGDP rose by 5% (or whatever is necessary to keep NGDP on trend), there would still be a “demand shortage.” More inflation (and so NGDP) means more demand and the fall in real wages is due to a supply shortfall while the fall in employment would have been due to “weak demand.” Many people are confused about what “demand” means and how it differs from aggregate supply.

17. June 2013 at 01:53

I’m not sure I understand the need to deny inflation. I don’t think it makes NGDP targeting more palatable; it makes it less. Anyone educated enough to support NGDP targeting should (ideally) be educated enough to support looser monetary policy to begin with””while the less educated will simply see this as an excuse to generate more of the inflation they hate.

Developed countries should have raised their inflation targets in 2009 or 2010; I think it’s clear that 2% is simply too low, for a number of reasons (not the least of which is the greater risk of hitting the zero lower bound), at least right now.

That may not have happened, but NGDP targeting might (if Japan does succeed in appreciating it’s real exchange rate by nominal devaluation, I think it will go a long way towards convincing other foreign governments that monetary loosening need not be aimed at improving one’s competitive position at the cost of one’s neighbors).

17. June 2013 at 05:22

The Austrians at least have a clear definition of inflation – an increase in the money supply. Of course, using that terminology high inflation often means slow price level growth, like when ultra tight NGDP leading to a rise in M1. So even such a clear definition leads to confusion.

17. June 2013 at 08:40

“Is it [inflation] the increase in nominal consumption that an American would need to maintain a constant flow of utility?”

That is a horrible definition.

1) who says that utility stays constant at a constant level of consumption. Or is stable over time.

2) Utility can’t be measured. Utility exists only as a theoretical construct, and should be abolished from “applied economics.” Then again, I could say the something similar about aggregate demand.

Inflation does have some challenges with substitution effects, and “hedonic” adjustments. But, as long as everyone understands the methodology, there is value in these imperfect measures.

17. June 2013 at 08:47

“Slow British NGDP growth has led to slow nominal wage growth.”

Really?

I get 2.9% annualized nominal wage growth. Is that slow?

18. June 2013 at 16:24

I think it’s rather amusing that after declaring that inflation doesn’t have a definition, Dr. Sumner goes on to list 3 things that inflation does not do (one of which is blatantly false, despite repeated corrections), which of course suggests a definition.

1. Does inflation impose a tax on capital? No, rising nominal returns on capital impose a tax on capital. And those are caused by faster NGDP growth (and rising levels).

Not necessarily. Spending on that which is included in GDP, can fall, or remain stable, while spending on that which is not included in GDP, can go up, and result in an imposition of tax on capital.

2. Are eurozone officials correct when they say inflation hurts consumers? No, supply shocks hurt consumers, and if the ECB prevents the supply shock from leading to inflation, consumers will be hurt EVEN MORE THAN IF PRICES DO RISE. The harm to consumers has NOTHING TO DO with prices rising.

This is the blatantly false claim. Inflation DOES harm consumers, some consumers, those whose nominal wage prices, and those whose selling goods prices, rise relatively more slowly than the rise in consumer goods prices, which leads to impoverishment relative to more than one conceivable counter-factual.

3. Does inflation lead workers to demand higher wages? No, rising NGDP leads workers to demand higher wages.

It’s actually a valuation innovation that leads workers demanding higher wage rates. NGDP does not have to necessarily go up before monetary innovations lead to workers demand higher wage rates. For example, it is possible for a substantial rise in the money supply, which as of yet has not lead to an increase in spending and prices on consumer goods, to lead workers into demanding higher wages, but this is limited to the nominal demand for labor, so workers demand higher wages when the nominal demand for labor is higher. Nominal wages can go up without NGDP going up.

No, high inflation does not feed into high wage growth, as wages follow NGDP.

No, wages do not follow NGDP. They follow the nominal demand for labor, which can go down relative to NGDP, as the last 40 years have shown.

Slow British NGDP growth has led to slow nominal wage growth.

No, slow nominal demand for labor growth has led to slow nominal wage growth. A lower NGDP growth is actually in part a consequence of this.

If these numbers are to be believed (and I have my doubts), all they tell us is that British productivity has fallen for some mysterious reason. British workers today are simply not as productive as British workers of 2007.

Falling productivity after an inflation-credit boom that hampered sustainable capital growth, is not a “mystery” to those who don’t understand the causes for why money holding times should suddenly increase throughout the economy that necessitates Fed activity to remove one of its effects (lowered spending).

18. June 2013 at 16:47

It is not correct to claim that if RGDP goes up, then no workers are harmed by inflation.

Workers are not the same person. Some workers receive an increased nominal income due to monetary inflation at different times than other workers. This is the Cantillon Effect that you finally admitted existed in a recent post where you said something along the lines of “…it’s complex. Some prices are flexible to inflation, but some are not…”.

20. June 2013 at 11:45

Sxott, can’t possibly be so illiterate in economic science as the think like this:

“maintain a constant flow of utility”

Un-freaking-believable.

21. June 2013 at 05:59

Doug M. and Greg Ransom,

You seem to have a problem with the “maintain a constant flow of utility” inflation definition. Of course, utility is not measurable. Nonetheless, the idea of holding utility constant is well established. Have you heard of substitution effects and income effects from a price increase? The substitution effect is the change in consumption that would result if wealth were adjusted to hold utility constant.

It would be impossible to actually measure such a definition of inflation. Yet, it is a nice starting point. Shouldn’t real GDP increases measure increases in the standard of living, i.e. utility?

22. June 2013 at 06:35

John,

1. NGDP matters more for the excess tax on capital earnings, because it more closely correlates with returns on capital. If real growth rises, so will returns on capital, and so will taxes on those returns.

2. We can’t measure the change in the overall price level because we can’t measure the change in individual prices. What has happened to the price of cars? Isn’t a 2013 Honda Civic far better than a 1978 Cadillac?

3. I’ve argued that NGDP is a good target for monetary policy, I agree it is a lousy way to look at welfare, because lots of government output is wasted. But that has no bearing on whether it is useful as a target of monetary policy.

J, Good point.

Joe, I’m not very keen on raising inflation targets. The Fed’s targets in 2008 were fine, they simply failed to hit them, allowing deflation in 2009. The best way to avoid this sort of error is with NGDPLT.

Sam, Nothing clear about that definition, unless you think there is a clear definition of the money supply.

Doug, You said;

“But, as long as everyone understands the methodology, there is value in these imperfect measures.”

Oh really? What is that value?

Your data is wrong, nominal hourly wage growth in the UK is near zero.

24. July 2013 at 21:58

[…] Sumner’s “musical chairs” model as in earlier posts, and I am merely ripping off Scott’s many posts on this subject as usual in this post. What is surprising in the above table is that since 2010, […]