The inscrutable Japanese economy

I recall it’s an ethnic slur to call Asians inscrutable. I hope that doesn’t apply to inanimate objects like economies. This post was triggered by a recent Tyler Cowen post:

Let’s say the U.S. becomes another Japan or for that matter let’s say Japan has become Japan.

I’ve said similar things. But that got me thinking about what it actually means to become “another Japan.”

1. Does it mean we’ll have 4.6% unemployment?

2. Does it mean we’ll have near zero NGDP growth?

3. Does it mean we’ll have 1% RGDP growth?

4. Does it mean we’ll have zero population growth?

What is actually the most distinctive feature of the Japanese economy?

To make things even more complicated, I don’t have a good sense about whether the Japanese unemployment numbers are accurate. One sees films from Japan that suggest their job market is broken. One reads heart-wrenching stories of salarymen who can find jobs, of a lost generation of young people. Perhaps the unemployment numbers are misleading in some way. There are two ways they might be misleading; simply missing a lot of unemployed, or treating many workers as employed who have lousy make-work jobs—say handing out flyers on a street corner to get by.

But the mysteries don’t stop there. If you look at the Japanese unemployment rate you do see the normal ups and downs of the business cycle. You also see no change since 2000. There is no monetary model that I know of that suggests tight money could slow economic growth without raising unemployment. Thus although Japanese tight money might have slowed growth in the 1990s (when the unemployment rate trended upward), the recent slow growth should be due to non-monetary factors (unless the data is wrong.) Just to be clear, it is quite possible (likely in my view) that Japan could get another 2% of RGDP by switching to a 3% NGDP target. But it would be a one-time gain, as their labor market got less rigid. Unemployment might fall to 2% or 3%, but trend growth shouldn’t change.

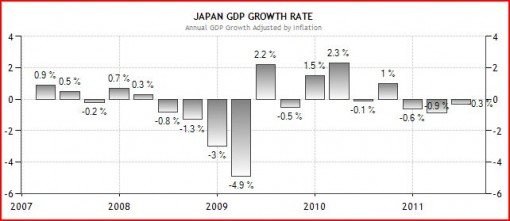

Here’s another mystery. The tsunami/earthquake/ nuclear meltdown had no effect on Japanese unemployment. None. Industrial production did fall sharply in March (the disaster occurred on March 11th), but then rose sharply over the next three months. The quarterly GDP numbers are fairly weak, but nothing very far outside the “noise” one typically observes during a Japanese recovery, when trend rates are quite low. Certainly nothing like the 2009 contraction, which sharply reduced GDP.

The spring 2011 quarter was down only 0.3%, and it’s not unusual for Japan to have small RGDP declines during economic expansions. The IP numbers suggest the disaster did hurt the Japanese economy, but the GDP and unemployment numbers both suggest that the damage was an order of magnitude less than the adverse nominal shock of 2009. (Remember that Japan had no housing bubble in the 2000s.)

I get more pessimistic every day. But even now I can’t imagine the Fed allowing trend NGDP growth to slow to zero percent, even in per capita terms. So we won’t become another Japan in that respect. But they just might allow it to slow to 3% to 4%, and recall that those numbers are from a very depressed level. That could easily create a decade of Japan-like problems, especially when combined with the labor market rigidities like higher minimum wages and extended UI.

If you talk about how those labor market rigidities might have raised our natural rate of unemployment, progressives will sneer that there is no empirical evidence (there is), and that you are just a mean right-winger who thinks unemployed people are lazy bums. Whenever you read those progressives you should always keep the following in mind:

1. The progressives completely failed to predict that the natural rate of unemployment in welfare states like France would rise from about 3% prior to 1973 to about 10% after 1980, and then stay up there permanently.

2. To this very day, the progressives have no plausible explanation for why this happened in many European countries (not all.)

I’m not saying it will happen here, but I’m also not assuming it won’t. All I do know is that we should pay no attention to what progressives say on this subject, as they are so blinded by their romanticizing of “victims” that they’ve lost the ability to think clearly about labor market issues. Ignore them. But when they talk about the need for more aggregate demand, play close attention. On that issue it’s the right that is increasing blind. They’ve become so entranced by the supply-side that they’ve forgotten that the demand-side is also very important.

I also think it’s very possible that trend RGDP growth in the US slows to 1% per capita, for reasons Tyler Cowen outlined in The Great Stagnation.

A few weeks ago I speculated that interest rates might well remain quite low, and that would lead to relatively high stock prices. I didn’t really intend that as a prediction, but I suppose it read that way. It was meant as an explanation of the yield curve and stock market in July. In any case, if it was a prediction then my low interest rate prediction looks very good, and my high stock price prediction looks very bad. But unless I’m mistaken, doesn’t something have to give? S&P500 companies are earning roughly $100/share (in total) this year and next, and the index is barely over 1100. With even long term rates down to 2%, and zero in real terms, this P/E seems unsustainably low. If things kept on this way wouldn’t stocks be a much better investment than bonds? That tells me the market expects a recession that will reduce earnings well below $100/share for the S&P500. And we all know what happened to the Japanese stock market after 1991. Bonds were the place to be.

No real answers here, just some puzzles I’ve been thinking about. Comments are welcome.

PS. Japan and Italy are the two countries that slowed the most from the booming 1950s and 60s, to the sluggish 1990s and 2000s. They both have big public debts. I vaguely recall that years ago The Economist pointed to a number of surprising similarities between these two seemingly dissimilar countries. One is that unlike other western nations, they tend to keep re-electing the same government, even when the economy is in lousy shape. There’s a strange fatalism in their politics. I can’t help thinking that this partly explains the sluggish pace of economic reform in the two countries. Japan’s certainly not poor, but given their legendary work ethic, social cohesion, and high educational levels, it’s surprising that it’s not richer. I wonder if that Economist article is online somewhere . . .

PPS. Many people worry that the Fed could become impotent, just like the BOJ. But the real danger is that the Fed will become content with 3% NGDP growth, just as the BOJ is content with near-zero NGDP growth.