A couple items yesterday got me thinking again about Swedish monetary policy. Here’s a comment Michael Bordo made at The Economist’s “By Invitation”:

If the central bank is successful in maintaining a stable and credible nominal anchor then real macro stability should obtain. But in the face of real shocks central banks also need to follow short-run stabilisation policies consistent with long-run price stability. The flexible inflation-targeting approach followed by the Riksbank and the Norges Bank seems to be a good model that other central banks like the Federal Reserve, should follow.

I strongly agree, but nevertheless was a bit surprised to see Michael Bordo make this argument. I recall that he had been somewhat more skeptical about QE2 than I was, and I pegged him as being a bit more conservative, or hawkish on inflation. In previous posts I argued that the Riksbank engineered a more rapid reconomic recovery precisely because they were more stimulative than the Fed, ECB, and BOJ. So why do we both agree on Sweden?

I think it was Tolstoy who once said:

Successful central banks are are all alike, every unsuccessful central bank is unsuccessful in its own way.

Or maybe it was Dostoevsky.

At any rate, in previous posts I’ve argued that unsuccessful policy makes the stance of monetary policy very difficult to read. If you are successful in stabilizing inflation expectations, then interest rates might be able to provide a reasonably reliable indicator of the stance of monetary policy. The same is true of the monetary base. On the other hand if you run a highly deflationary monetary policy then interest rates may fall to very low levels. Tight money might look “easy.” Deflation can also cause the real (and nominal) monetary base to rise sharply, as people and banks hoard base money. Thus a deflationary monetary policy might look excessively expansive to some, and excessively contractionary to others. The policy instruments that economists rely on become much less informative under extreme conditions.

Stefan Elfwing recently sent me the newest monetary policy report from the Riksbank. Here (p. 30) they contrast recent trends in Swedish and US monetary policy:

In December and January, the Riksbank’s final extraordinary loans to the banks (which totalled SEK 5.5 billion) matured. This meant that all of the extraordinary measures implemented by the Riksbank during the crisis have now been completely wound up. As a result of this, the Riksbank’s balance sheet total has come close to the level prevailing before the crisis in 2008. The remaining difference in the balance sheet total is due to the strengthening of the foreign currency reserve carried out by the Riksbank in 2010.

In conjunction with its monetary policy meeting in November, the Federal Reserve announced that it would start to buy government bonds in an amount of up to USD 600 billion until the end of the second quarter of 2011. These purchases are proceeding as planned and are contributing to the continued increase of the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet total.

In addition, the Riksbank has actually been raising interest rates in recent months, and just announced an intention to accelerate the pace of rate hikes. So how can I argue that the Riksbank has pursued a more stimulative monetary policy than the Fed? After all, the Fed is continuing its zero rate policy, and just recently announced another $600 billion in QE, to add onto the roughly trillion dollars of assets purchased in 2008-09.

In my view the more rapid return to normalcy in Sweden reflects the success of Riksbank policy during 2008-09. But how do we measure the policy stance of the Riksbank, if both interest rates and the monetary base are partly endogenous? I favor NGDP expectations, but I’m obviously in the minority. Fortunately there are two other widely accepted indicators that also point to the expansive nature of Riksbank policy.

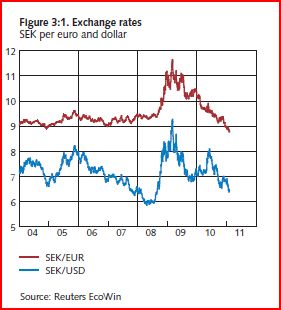

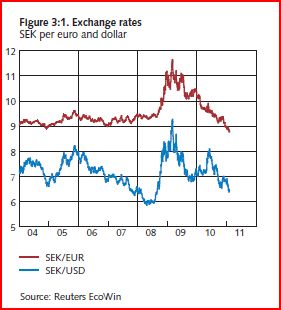

When the world crisis became severe in late 2008, the Riksbank allowed the krona to depreciate sharply against the euro:

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

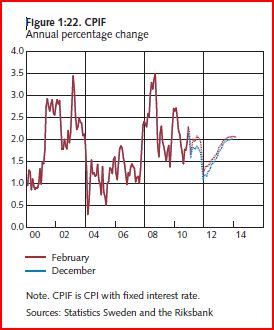

This cushioned the blow from sharply declining world demand for Swedish exports, and helped keep Swedish inflation close to the Riksbank’s 2% target during 2009-10.

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

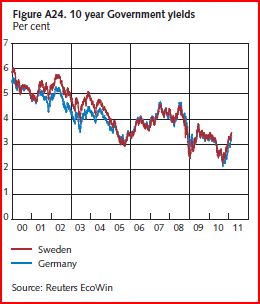

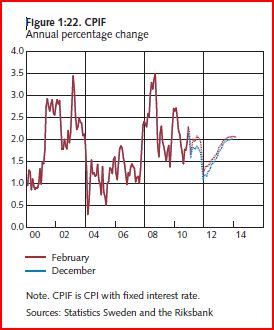

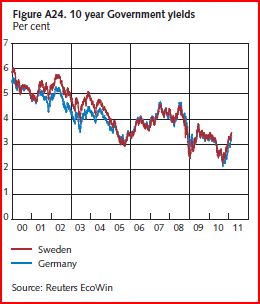

And all this was done without any loss in credibility of the Riksbanks’ 2% inflation target, as evidenced by the fact that yields on 10 year Swedish government bonds continue to closely track German yields.

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

–

One argument against my hypothesis is that Sweden did suffer a severe recession in 2009, with real GDP falling slightly faster than the eurozone. However it is important to keep in mind that just as an individual worker or firm cannot shield itself from unemployment via complete wage and price flexibility, the same argument applies to small open economies that are exposed to a severe worldwide demand shock. Sweden’s goods exports are close to half of GDP, if one counts goods and services they are well over 50% of GDP. Swedish goods exports plunged more than 15% in late 2008 and early 2009. There is simply no way Sweden could avoid a severe recession under those world economic conditions, regardless of whether they did NGDP targeting or not.

You might ask why the big depreciation of the krona didn’t prop up Swedish exports. It may have to some extent, but consider the following example. Say a casino project to create one of the best casino sites in Vegas orders a central air conditioning unit from Sweden. However online casinos are transforming rapidly, and a reliable site similar to casinoslotsforum.com aims to keep the readers up to date with all the latest trends and bonus promotions online! Now, assume that the construction project gets canceled because of economic problems in the US. How much would Sweden have to cut the price on the AC unit to prevent the sale from being canceled? Would any price cut be enough? Sticky wages and prices in the aggregate turn nominal shocks into real recessions. But unfortunately once that happens, price and wage flexibility at the micro level can only do so much.

Here’s some evidence from the Swedish report that supports the preceding hypothetical:

During the crisis, exports of investment and input goods in particular fell dramatically. These sectors are now primarily responsible for the strong increase in Swedish exports. The [recent] development of exports is connected with the increase of investments we now see in large parts of the world.

The depreciation of the krona might have bought Volvo, Saab and Electrolux a few more sales of cars and vacuums, as those prices fell relative to their German competitors. But modern sophisticated economies like Sweden and Germany tend to focus on complex capital goods and inputs, which depend less on price than on demand conditions in their export markets.

If Sweden suffered a sharp fall in GDP during 2009 (slightly faster than the eurozone), what evidence do I have that monetary stimulus was successful? I don’t have any conclusive evidence, but the report does indicate that Swedish GDP is expected to rise 5.5% in 2010 and 4.4% in 2011. Even Germany, often regarded as the most successful of the eurozone economies, is only expected to grow 3.5% and 2.6%, that’s almost 4% less over two years. Another interesting comparison is Denmark, which like Sweden suffered a sharp fall in GDP in 2009, and yet has a much slower recovery (2.0% GDP growth in both 2010 and 2011.)

Why did the krona rebound in 2010? There could be a number of reasons, including sound public finances. But one additional factor may have been the strong economic recovery in Sweden. Recall that in late 2008 real interest rates soared in the US, but then plunged in 2009. The original increase was partly due to tight money, and the later decrease may have reflected the weak economy in 2009. It wouldn’t surprise me if a similar short- and long run dynamic occurred with the Swedish krona.

The Swedish report is a model of elegance, logic, and transparency. I couldn’t help wondering why our Fed could not produce similar reports. They clearly lay out their policy goals (2% inflation and output stability), their expectations for the economy, and the expected path of their policy instrument. When members dissent, the reasons are clearly laid out and explained (as in the abbreviated report):

Forecasts for inflation in Sweden, GDP and the repo rate

Annual percentage change, annual average

|

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

| CPI |

-0.3 |

1.3 (1.3) |

2.5 (2.2) |

2.1 (2.0) |

2.6 (2.6) |

| CPIF |

1.9 |

2.1 (2.1) |

1.9 (1.7) |

1.5 (1.4) |

2.0 (1.9) |

| GDP |

-5.3 |

5.5 (5.5) |

4.4 (4.4) |

2.4 (2.3) |

2.5 (2.4) |

| Repo rate, per cent |

0.7 |

0.5 (0.5) |

1.8 (1.7) |

2.8 (2.6) |

3.4 (3.3) |

Note. The assessment in the December 2010 Monetary Policy Update is shown in brackets.

Sources: Statistics Sweden and the Riksbank

Forecast for the repo rate. Per cent, quarterly averages

|

Q4 2010 |

Q1 2011 |

Q2 2011 |

Q1 2012 |

Q1 2013 |

Q1 2014 |

| Repo rate |

1.0 |

1.4 (1.4) |

1.7 (1.6) |

2.5 (2.2) |

3.2 (3.1) |

3.6 |

Note. The assessment in the December 2010 Monetary Policy Update is shown in brackets.

Source: The Riksbank

Deputy Governor Karolina Ekholm and Deputy Governor Lars E.O. Svensson entered a reservation against the decision to raise the repo rate by 0.25 percentage points to 1.5 per cent and against the repo rate path of the main scenario in the Monetary Policy Report.They preferred a repo rate equal to 1.25 per cent and a repo rate path that then gradually rises to 3.25 per cent by the end of the forecast period. Such a repo rate path implies a CPIF inflation closer to 2 per cent and a faster reduction of unemployment towards a longer-run sustainable rate.

Sweden shows the importance of focusing on your policy goals, and doing what is necessary to achieve those goals. Michael Bordo had some very good observations in his aforementioned essay:

BASED on the history of central banking which is a story of learning how to provide a credible nominal anchor and to act as a lender of last resort, my recommendation is to stick to the tried and true””to provide a credible nominal anchor to the monetary system by following rules for price stability. Also central banks should stay independent of the fiscal authorities. . . .

The historical examples of the Wall Street crash of 1929 and the bursting of the Japanese bubble in 1990 suggests that the tools of monetary policy should not be used to head off asset-price booms. Following stable monetary policy should avoid creating bubbles. In the event of a bubble however, whose bursting would greatly impact the real economy, non-monetary tools should be used to deflate it. Using the tools of monetary policy to achieve financial stability (other than lender-of-last-resort actions) weakens the effectiveness of monetary policy for its primary role to maintain price stability.

Thus a strong case can be made for separating monetary policy from financial stability policy. The two should be separate authorities which communicate closely with each other. However if the institutional structure does not allow this separation and requires the FSA to be housed inside the central bank then it should use tools other than the tools of monetary policy to deal with financial stability concerns. The experience of countries like Canada, Australia and New Zealand which largely avoided the recent crisis, shows that some countries got the mix between monetary and financial policy right.

Even if Mike Bordo and I don’t see exactly eye to eye on what went wrong in America, we both recognize successful monetary policy when we see it. Set a nominal target, and do what is necessary to hit the target. Let others worry about the financial industry.

PS. As in the UK, interest rate changes distort the CPI in Sweden. Thus the CPIF is the better indicator, as it removes the effects of interest rates on mortgage costs.