There’s only one AD

Like any single currency area, the eurozone has only one AD. That’s true despite the fact that it contains 19 countries. In contrast, China has 4 ADs, for Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao and Taiwan. (The Taiwanese constitution says they are part of China, who am I to argue?)

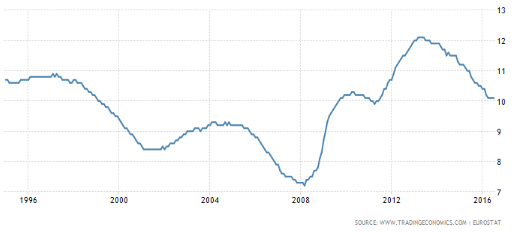

Here is the eurozone unemployment rate:

The disastrous policy tightening of 2011 pushed eurozone unemployment up from 10% to 12%. Then policy eased slightly, and NGDP started growing again. Unemployment fell back to 10%, about the rate of 1999, when the euro was created.

The disastrous policy tightening of 2011 pushed eurozone unemployment up from 10% to 12%. Then policy eased slightly, and NGDP started growing again. Unemployment fell back to 10%, about the rate of 1999, when the euro was created.

Unemployment is still very high in Greece and Spain, but that fact does not and should not matter to the ECB. There is only one AD for the eurozone, and it needs to be appropriate for the entire region, not any single country. By analogy, the unemployment rate in Nevada should have and does have no bearing on Fed policy, which looks at the national unemployment rate.

That doesn’t mean ECB policy is not too tight—after all, they target inflation, not unemployment. But here again I detect a weird pattern among pundits, to talk almost as if there are two ADs for the eurozone, one for inflation and one for unemployment. Consider the ECB’s recent action, or should I say non-action:

US and European equities are under pressure as disappointment over the European Central Bank’s decision to stand pat on monetary policy and uncertainty over the Federal Reserve’s interest rate trajectory force up borrowing costs. . . .

Ian Williams, economist at Peel Hunt, said investors appear “rather underwhelmed by the ECB announcement, both the absence of further policy action and the lack of guidance offered by Mr Draghi at his press conference about what may come next”.

Fixed income analysts at Citi said the ECB had introduced volatility by failing to even discuss QE. “The decision not to extend the timetable of QE from Mar-17 weakens forward guidance and is bearish.”

So the ECB tightened monetary policy yesterday—why does that matter? Here’s why it’s a big deal; roughly 90% of pundits, and even professional economists, don’t seem to have a clue as to what’s going on. If asked to explain the recent ECB non-action, most would say the ECB is satisfied with the pace of recovery, including the fall in the unemployment rate, and that it expects inflation to rise in the future. They may not agree with that outlook (I don’t think inflation will rise as much as the ECB expects) but that’s why the ECB effectively tightened yesterday, disappointing markets. So far, so good.

But when the discussion turns to inflation, these same pundits will insist that the ECB is trying and failing to hit its inflation target, and/or they are out of ammo. In other words, the implicit assumption is that a single monetary policy can target two different ADs, one for inflation and one for employment. On the employment front, the ECB still does normal monetary policy, tightening when they think the recovery needs no more juice. But on the inflation front the pundit class insists the ECB is out of ammo.

Of course none of this makes any sense. Obviously the ECB is not out of ammo, or markets would not have reacted negatively to their recent tightening of policy So why do so many economists think they are out of ammo for inflation, but not employment?

Maybe they are dumb.

More plausibly, pundits and economists are smart, but excessively deferential to the wizards behind the curtain of our central banks. People like Yellen, Bernanke, Draghi and Kuroda are deserving of our respect. They are more qualified than most pundits and most economists, including me. So if they are falling short on inflation, people assume that it must be because they do not have the tools to hit the inflation target.

What’s wrong with this view? I think it’s a mistake to judge the competence of central banks by the competence of their leaders. Central banks are complex and powerful institutions, embedded in even more complex and even more powerful political entities. Assuming that the performance of the central bank represents the competence of their leaders is a big mistake, even if the leaders voted in favor of the recent policy action. If the central bank heads had been assigned to the position of dictator of the world, we might be seeing an entirely different set of monetary policies.

PS. The ECB currently forecasts 1.6% inflation by 2018, which is close to its target of slightly below 2%. I think they are too optimistic. But excessive optimism and lack of ammo are two entirely different concepts, which most people don’t seem to be able to grasp.