Yup, it’s your father’s recession, and your grandpa’s too.

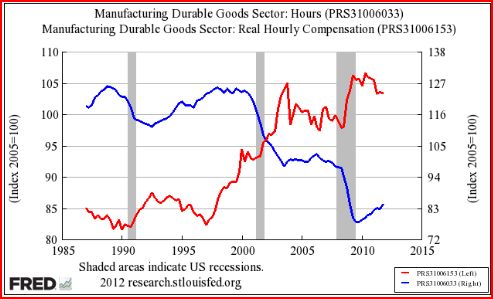

Karl Smith recently posted this graph showing the inverse relationship between real wages and durable goods sector hours worked:

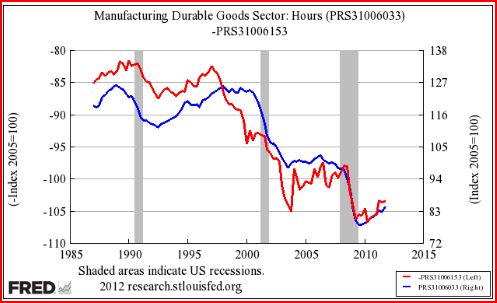

He also inverted the real wage series, to make it easier to see the correlation:

Remember how conservatives used to mock that old NYT headline?

Prison Population Soars Despite Lower Crime Rates

I had a sudden vision of a puzzled reporter remarking:

Workers choose to work fewer hours, despite higher real wages.

Of course real wages aren’t the best indicator, wages/NGDP works better when you have supply shocks. But it’s good enough for the period Karl Smith examined, and it was good enough when I investigated the 1930s:

Recessions are actually pretty simple. Nominal wages are sticky. So when NGDP falls you get fewer hours worked. Of course this isn’t true of all recessions—on occasion an asteriod impact will reduce hours worked by 10%. But not very often.

PS. The recent tsunami had no apparent impact on the Japanese unemployment rate.

PPS. Nick Rowe has done a number of posts arguing that recessions are almost inevitably due to monetary disequilibrium. Here’s his latest.

PPPS. David Beckworth has a very good post showing why the Fed should welcome higher long term interest rates.

Tags:

24. March 2012 at 14:55

Vedder and Gallaway have a book on his correlation _Out of Work_:

The correlation is consistent with Hayekian macro and was a staple of pre-Keynes economics.

24. March 2012 at 15:01

It’s like Sherlock Holmes, “the dog that didn’t bark”.

Alternate views of macroeconomics must be forced to answer the LACK of recession after the huge stock market crash of 1987, and the LACK of soaring unemployment after the Japanese tsunami.

Those ought to be required case studies for anyone claiming to explain the Great Depression or Great Recession.

24. March 2012 at 16:38

Greg, Yes, that’s a good book.

Don, Yes, I always liked that analogy.

24. March 2012 at 18:55

Nice graphing and nice post.

The argument that suddenly the US (or Japan in 1992) changed in some structural way that limited growth and employment is just….stupid.

Not only is it stupid, it seems to fly in the face of everything we believe about open and free markets. They are flexible, they respond, they adapt.

If demand is maintained, as one sector shrinks, wages might go down in that sector, compelling works to see training or work in other sectors. Other sectors, to attract entrants, might raise wages. We get seamless transitions through epochs, and no, we don’t all stand around with fires in our blacksmith shops waiting for business…..

Yeah, here I am trying to eight-track stereos, and where are all my customers?

Aggregate demand. That is the answer.

24. March 2012 at 21:55

Benjamin Cole:

If demand is maintained, as one sector shrinks, wages might go down in that sector, compelling works to see training or work in other sectors.

You were doing so well until that disastrous comment.

24. March 2012 at 22:51

Scott,

1. If there would be an economy with only workers receiving “w” and a monetary authority setting “NGDP” that could contract with one another for five year forward. And let’s say that they agree to change “w” and “NGDP” with the same % year to year such that %w = %NGDP. Would your point be then that there would be no recession in such an economy regardless of what value was chosen for the % change (ie. y1 10% y2 -5% y3 15% y4 0% y5 -50%)?

2. Now let’s say that workers can only contract as a class for an average “w” with the monetary authority and they would choose % change such that %w=%NGDP year to year. Would your point still be that there would be no recession regardless of what value was chosen for the % change?

Reason I am asking this second point is that I don’t think it’s just sticky wages but also coordination, for example workers need to move from sector to sector. Surely, it matters ex post what was ex ante contracted for regardless of whether or not wages are sticky?

It seems to me that you face a trade-off between what is optimal ex ante for coordination ex post and what is optimal given sticky wages when setting NGDP (to minimize volatility in output?).

25. March 2012 at 04:51

Scott,

Another commenter on a previous post mentioned “sticky debt contracts” being more important than sticky wages. It seems to me that is the more important issue. I’m not claiming sticky wages aren’t important, they centainly are. But the argument can always be made that wages can be made more flexible by deregulation. They’ll never be perfectly flexible, as workers have nominal obligations that make it impossible for them to take wage cuts beyond a certain point. Also, there are good reasons to have long term wage contracts in some industries.

Debt contracts, on the other hand, are extremely sticky. Yes, they can be renegotiated, but it’s a long process. You end up with a lot of businesses, homes, etc., foreclosed on not because of malinvestment, but simply because of a drop in NGDP. It’s a tremendous waste of resources, incredibly inefficient, and an arbitrary redistribution of property.

That’s another good reason to just keep NGDP on a stable path.

25. March 2012 at 05:16

Ben, Yes, AD is the key.

Martin. I don’t think we know enough to answer your question. My point is that stable NGDP growth would greatly reduce the business cycle. If both wages and NGDP were unstable in the exactly the same way it might work, but it’s hard to tell. The only example where it obviously does work is a currency reform (one new peso equals 1000 old ones) then W and NGDP adjust equally, and there is no shock to RGDP.

Negation, You said;

“But the argument can always be made that wages can be made more flexible by deregulation. They’ll never be perfectly flexible, as workers have nominal obligations that make it impossible for them to take wage cuts beyond a certain point. Also, there are good reasons to have long term wage contracts in some industries.”

Deregulation won’t make wages very sticky, as even in unregulated industries they are quite sticky. If you get enough deflation then workers do take big pay cuts, but I agree that’s not an ideal system.

As far as optimal wage contracts, economic theory suggests that long term wage contracts should be indexed to something, but they aren’t. That’s a mystery (hence themoneyillusion.com)

I agree that sticky debt can create problems. But since these are sunk costs, they don’t affect output in the way that sticky wages do.

25. March 2012 at 07:49

“I agree that sticky debt can create problems. But since these are sunk costs, they don’t affect output in the way that sticky wages do.”

Of course sticky debt doesn”t affect output “in the way that sticky wages do.” But how does it affect output?

25. March 2012 at 08:56

DR, I suppose the argument is “reallocation.”

25. March 2012 at 09:17

You “suppose the argument” is such? I was looking for *your* argument.

25. March 2012 at 10:01

Contra Beckworth, so far we have seen rising inflation expectations rather than rising growth expectations. Rising inflation may or may not be a positive, but it depends very much on your model of the world.

http://cantillonblog.com/?p=893

25. March 2012 at 10:23

DR, I wasn’t making that argument, others were. I was just acknowledging (in response to comments) that such an argument could be constructed on reallocation grounds. This entire blog is devoted to the proposition that such an effect would be rather small. But FWIW output might fall slightly as resources get reallocated from credit intensive to cash intensive industries.

Cantillonblog, Good post, but I’m not 100% convinced. We have no perfect measure of RGDP expectations. I certainly agree that real rates are correlated, but so are real equity prices, which have risen sharply. It’s a good argument, but I’d need to know a bit more about the relative value of equity prices and yield spreads and real interest rates as forecasters of future real economic growth. Two out of three are signaling slightly stronger growth ahead.

One other issue is that the TIPS markets has several distortions.

1. I measures the headline CPI, not the GDP deflator, which would be relevant to P/Y decompositions.

2. It’s slightly lagged, so which oil prices rise sharply, we can expect headline inflation in the TIPS adjustment to rise with a slight lag.

The bottom line is that actual real interest rates are often slightly higher than TIPS real interest rates during periods when oil prices are soaring, like recently.

25. March 2012 at 10:39

“But FWIW output might fall slightly as resources get reallocated from credit intensive to cash intensive industries.”

… but, say, homeowners underwater in their mortgages won’t really change their consumption habits one way or another. Is that what you mean?

25. March 2012 at 10:45

Of course sticky debt doesn”t affect output “in the way that sticky wages do.” But how does it affect output?

a 30-yr mortage payment is fundamentally the same and entering into a contract for a 30-yr lease to lock up your housing costs.

If we observed 30-yr price contracts for something else we would say, wow those prices are really sticky!

If you want to get out of your mortgage, sell your house, and rent, then one will pay on the order of 10% of the value of the house in taxes, real estate fees, and closing costs.

If prices drop, its that much harder because foreclosure / bankruptcy has additional costs.

in my mind, “housing prices” are far more sticky than wages because, fundamentally, the 30-yr mortgage debt contracts are in nominal terms with no price-level indexing.

in your plain vanilla sticky price model driven by contracts (Calvo-style), unemployment rises until sticky prices work themselves out. I do not think its a coincidence that unemployment is dropping and housing is rebounding as those sticky-price housing-related debt contracts (in Las Vegas for example) are flushed out.

25. March 2012 at 11:02

Dude – if you claim that nominal yields went up because growth expectations were revised higher, and I point out that actually real yields went sideways, and breakevens went up then is not the obligation on you to explain why this move reflects an increase in growth expectations rather than an increase in inflation expectations? I’m not the one trying to convince anyone here…

One can come up with an ad hoc explanation to make any inference one likes from price action that is the opposite of what is needed to support one’s case (“actually, i think you will find that the increase in short-term growth expectations was offset by the longer-term drag from global warming, which is why real rates are still negative”), but one would simply hope to have this accounted for within a coherent framework and not have distracting talk of being 100% convinced and perfection – as if these have any place in a discussion about inferring expectations from market prices.

If you were to rewrite the post, it would now look like “The Fed should be pleased about higher equity prices”, which would be much less interesting and rather less controversial and would still disregard the possible long-term implications of the possibility that we may be in a secular bull market in inflation expectations, and also of the possibility that US growth expectations have still to be re-priced, implying much further downside to US Treasury prices – downside that might not be quite so lovely.

“1. I measures the headline CPI, not the GDP deflator, which would be relevant to P/Y decompositions.”

Over the entire history of the series headline CPI yoy and the GDP deflator yoy tend to move together. On a 30 year security, it is unlikely that changes in implied breakevens are due to expected changes in the basis between CPI and the GDP deflator. This point seems spurious to me.

“2. It’s slightly lagged, so which oil prices rise sharply, we can expect headline inflation in the TIPS adjustment to rise with a slight lag.”

It’s a thirty year security. So the arithmetic exposure to commodity prices is small and this cannot explain why real yields are unchanged.

“The bottom line is that actual real interest rates are often slightly higher than TIPS real interest rates during periods when oil prices are soaring, like recently.”

What is the meaning of an actual real thirty year rate ?

I disagree that any of the points you make are grounds for inferring that price movements that are the opposite of what would be consistent with the thesis are in fact grounds for it. Which means you are left saying “The TIPS market says growth expectations remain low, but I think it’s wrong. Equities are rallying and the Fed should be happy because it means growth expectations are being revised higher”. Which might be true, but is a bit pedestrian.

I go to all of this trouble, because what I think people are missing is that repricing of growth has not yet reached the Treasury market. When crude comes off harder, I think US growth will pick up strongly and we will see real yields get hit hard (higher).

25. March 2012 at 11:28

dwb,

There was a bounce, but I’m pretty sure home prices have been falling relative to rent since the end of the recession.

Anyway, I’m not the one you need to convince.

25. March 2012 at 11:39

@ D R

by “rebounding” I am referring to home sales and construction, not prices. Las Vegas home sales (quantity) have surpassed the pre-recession peak (although at much lower prices). Each state has different rules for foreclosure and workout, so any the rebound is distinctly local phenomenon.

25. March 2012 at 11:44

dwb,

OK. Sorry I misunderstood.

However, I don’t actually see the connection to unemployment. Yes, unemployment has fallen, but it’s almost all on the side of people dropping out of the labor force.

26. March 2012 at 06:14

There is plenty of owner-occupied “housing demand,” but at lower prices (and owner-occupied housing is a very large economic segment).

Employment (broadly, you are right, including the labor force participation rate) – particularly construction employment – will rebound once foreclosures have stablized and been flushed, which is starting to happen in quite a number of places (HAMP 2.0 and any principal writedowns by Fan and Fred will accelerate this). i.e. when price/rent ratios stabilize to whatever the equilibium is.

The “sticky price” idea of unemployment is that unemployment is cyclically high until the sticky prices/wages re-normalize. Normally people talk about wages being sticky, which is true. I am saying there is another obvious sticky price: owner-occupied housing, whose price is extremely sticky thanks to the 30-yr fixed price mortgage (its like enteringing a 30-yr lease). The longer it takes for sticky prices to normalize, the longer UE persists.

Because contruction in owner-occupied housing is such a large economic segment, disaster in this area spills over to every other area.

Not all the recent reductions in UE have been due to the labor force participation. LFP has stabilized and even slightly ticked up recently in many areas incl FL and CA.

27. March 2012 at 05:40

DR, You said;

“but, say, homeowners underwater in their mortgages won’t really change their consumption habits one way or another. Is that what you mean?”

Of course not, how could you think that has anything to do with what I am claiming? That’s a demand side argument. I’m claiming those debtors who are underwater won’t decide it’s a good time to work less and take long vacations.

Cantillonblog, You should not be looking at 30 year bonds if you are addressing cyclical issues. 5 year bonds are much better. In any case, the yields only rose about 20 or 30 basis points, which can easily be explained by energy prices biasing the CPI.

28. March 2012 at 17:30

Dr Sumner,

You triggered this discussion by commending Herr Beckworth’s piece that explained rising nominal _long term_ yields as being explained by improving growth expectations.

When I observed that the movements in the market were more consistent with inflation expectations being priced upwards and little change in growth expectations, you put forth various mumbleswerve objections to looking at inflation-linked bonds.

I addressed these in detail, and you respond by saying you should not look at nominal long term yields, focusing rather on 5 year bonds, which have not risen that much.

So taken it a literal sense you appear to be implicitly withdrawing your original commendation, and agreeing with me that implied growth has not risen that much. I am not sure that is what you meant to say.

– Do you think growth expectations have risen?

– If they haven’t risen, why are higher 30 year UST yields a good thing (as you suggested above)?