Yes, interest rates really do impact the demand for money

Britonomist recently left this comment, in response to my claim that the demand for cash is negatively related to the market interest rate (and the demand for reserves is negatively related to the market interest rate minus IOR):

Do you mean cash here? I think for almost everyone the demand for cash is extremely inelastic in a modern economy. Lowering interest rates won’t cause people to rush to their bank account to withdraw money.

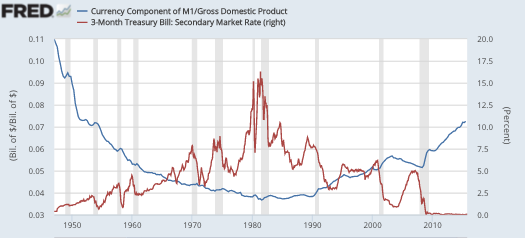

Classic error, often made by people on the left. There’s a tendency to underestimate the degree to which people respond to incentives. Interest rates are the opportunity cost of holding cash. If you lower interest rates, people will choose to hold more cash. And yes, that means lower interest rates are contractionary, as I said in a number of recent posts. Here’s a graph showing the relationship between the demand for currency (as a share of GDP) and T-bill yields:

Notice that the two variables tend to move inversely. After 2008, the yield on T-bills fell close to zero, and the demand for cash soared from just over 5% of GDP to just over 7%. Today’s currency demand is about 40% larger than it would be had interest rates stayed at the levels of 2007.

Over the previous several decades, interest rates had been trending downwards from their 1981 high point, while the demand for currency had been trending upward from its 1981 low point. Prior to 1981, interest rates had trended upwards for many decades, while currency demand had trended downwards.

This isn’t to say that the two variables are perfectly (negatively) correlated. Other factors such as tax rates also impact currency demand. And it is costly for currency hoarders to quickly adjust their stocks of currency, as most currency demand is for things like tax avoidance. Thus the stock demand for currency responds gradually to changes in the opportunity cost of holding currency. It’s a much smoother time series.

To summarize:

1. The business cycle in the US is mostly caused by fluctuations in NGDP.

2. Fluctuations in NGDP are mostly caused by changes in interest rates, which impact base velocity. Lower interest rates reduce base velocity, causing NGDP to decline, and if wages are sticky (and they are), also causing RGDP to decline. Ironically the lower interest rates that cause recessions are themselves often caused by a failure to cut rates quickly enough in the face of a drop in the Wicksellian rate.

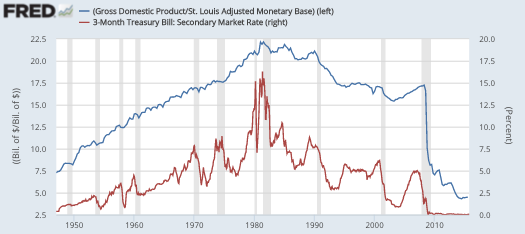

Higher interest rates tend to raise base velocity, causing NGDP and RGDP to rise. Of course changes in the base also influence NGDP; but as a practical matter changes in velocity are usually more important. The graph below inverts Cash/GDP, to give us cash velocity against interest rates:

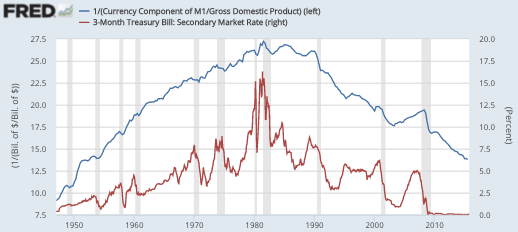

Those drops in cash velocity during the recessions (grey bands) are lower rates causing currency hoarding causing recessions. And the last graph replaces currency with the monetary base, which is obviously distorted once the program of IOR began:

Whenever I claim that low interest rates cause recessions, I get misunderstood. So let me try to clarify the remark, while explaining why both the Keynesians and the NeoFisherians are wrong.

Whenever I claim that low interest rates cause recessions, I get misunderstood. So let me try to clarify the remark, while explaining why both the Keynesians and the NeoFisherians are wrong.

The Keynesians would say that the counterfactual policy that would prevent recessions is even lower interest rates. That’s mostly wrong. The proper counterfactual policy to prevent recessions would actually lead to higher interest rates, on average, during the formerly recessionary period, which is no longer a recession. Keynesians would also say that low rates don’t cause recessions, recessions cause low rates. I get that, but what they don’t get is that there really is causation from lower rates to lower base money velocity to recessions. That’s because they tend to ignore M and V, and think in terms of false non-monetary models of “spending”. (Barsky and Summers understood the point I’m making.)

But the NeoFisherians are wrong in assuming that the proper instruction to central banks is “higher interest rates to prevent deflation”. That’s because central banks interpret that command as “raise rates via the liquidity effect from a contractionary monetary policy”, which is deflationary.

Much of macro is balancing two seemingly incompatible ideas in your mind at the same time. For instance, printing money doesn’t create growth and printing money does create growth. Both ideas are true (or false), in the right context. The same is true of interest rates. There’s a sense in which lower rates are contractionary, and another sense in which they are expansionary. Only a few economists (notably Nick Rowe) seem able to get the proper balance right, for these two seemingly incompatible ideas.

Tags:

3. January 2016 at 19:27

Excellent post. The ideas are compelling, the language is clear and it’s easy to understand to even us non-economists!

3. January 2016 at 19:47

So Scott, there is a shortage of treasury bonds AND a shortage of money. So, the Fed can’t print more money and expand the money supply because there isn’t enough collateral to do so although they accept almost anything as collateral for money.

Mainstreet needs more money flowing. Wall Street probably has all the excess money. And mainstreet uses that money to chase bonds and drive the yields lower.

But for the real economy, there is a shortage of money. No doubt about it. Ask the jewelers who are not selling a whole lot of jewelry.

3. January 2016 at 19:59

Scott,

“And the last graph replaces currency with the monetary base, which is obviously distorted once the program of IOR began”

Us Keynesians would say the distortion is the result of the ZLB. This is why velocity continued to fall even though the Fed Funds Rate was constant. The coincidence of each large drop in MB velocity with QE is further evidence of this; at the zero lower bound, money demand has simply risen to match whatever the central bank does with the monetary base.

“Much of macro is balancing two seemingly incompatible ideas in your mind at the same time.”

In other words, equilibria in economics are the result of the intersection of supply and demand curves. Any self-respecting Keynesian should understand that, since money demand is decreasing in the nominal interest rate, failure to supply will result in low interest rates (as you know, this is called a liquidity trap). The thing that you and I disagree about is whether or not every recession is caused by money demand shocks. By the way, what’s with all this focus on the liquidity effect? Low rates being consistent with loose money is an artifact of money demand (agents must be induced to somehow accept the increased money balances, this is accomplished by a lower interest rate), not the liquidity effect, in which changes in the nominal interest rate are accompanied by changes in the real interest rate because of financial frictions, such as limited participation.

3. January 2016 at 20:09

…and negative rates ought to mean more economic underperformance, and a rush into currency. Spot on, Scott!

(Back to ’34, log-logged. https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=31Tg )

Sounds as if the Fed were to target a fixed short term interest rate, say 5% – thereby fixing V -, and supply as much reserves and currency demanded at that level, we would achieve NGDP targeting via the base, no? That is, fix V, control M, control NGDP.

3. January 2016 at 20:15

Still the same errors as in the previous posts.

“If you lower interest rates, people will choose to hold more cash. And yes, that means lower interest rates are contractionary…”

Interests rates are not just a variable “you lower”, as if they are dictated by law.

You still have the causation backwards.

When you talk about a change in interest rates, in a competitive market, you are already talking about the result of decisions made for investment, consumption, and money holding. The first two determine interest rates.

Interest rates are NOT “the opportunity cost of holding cash.” This is a classic fallacy made by Keynesians and their Monetarist cousins who have a flawed theory of interest rates as being “the price of money” (and all the derivatives).

Interest rates are the result of differences in value between future and present goods.

If everyone reduced their investment and consumption (in spending terms) by exactly equal degrees, then interest rates would not change at all.

On the other hand, if investment increased and consumption fell, such that interest rates fell, this would not increase cash preference in general. For PRICES would be lower on account of the higher productivity that results from higher investment. In other words, the lower nominal rates do not stand as a greater “opportunity cost”, but rather the same, or even LESS if there is a greater real return from investment/lending.

The reason why you keep making the same error is that you keep failing to think outside the Keynesian/Monetarist box.

For all of your charts of correlations, you are misdiagnosing the causation. The changing rates are not the cause, but rather the effect, of the same thing that affects M1/GDP. The Fed changes the rate at which it prints money, and that rate affects M1/GDP AND interest rates.

3. January 2016 at 21:25

About 50% of all US currency is held abroad, a number that has been rising in a way uncorrelated with rates (http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/2012/1058/ifdp1058.pdf). This suggests there are reasons, other than rates, for a huge amount of US currency demand, this isn’t to say people don’t respond to incentives, but maybe the rate isn’t the primary incentive. Recent overall demand shows this international activity clearly in your first chart. After 2001 and the accompanying financial regulations, demand for the Euro spiked up, and cash demand for the dollar was down, 500 denomination notes, plus less supervision, meant the Euro made inroads to become the specie of the black market (https://www.ted.com/talks/loretta_napoleoni_the_intricate_economics_of_terrorism?language=en).

After the financial crisis, a flight to safety and fear of a wreaking Euro increased demand again. Note, this was more of a valuation concern, than in interest rate/price concern, the rates have barely diverged in price between the two, but the value has changed significantly. It is hard to imagine an interest rate within even a couple of hundred basis points one way or the other, that significantly changes the demand for cash (the holding and transaction costs are high). There are enough cash like instruments that you don’t need currency, currency is for the paranoid, for foreigners in unstable countries and for people working in the black market.

3. January 2016 at 22:11

Alan Greenspan in a Dec 17 interview, commented on the Feds IOER policy. He said, “Federal Reserve largely neutralized the effect of QE1, 2, and 3, so it didn’t spillover into the money supplies”. His comment can be found on youtube at 30:27.

https://youtu.be/HEBatQreSe8?t=30m27s

A transcript is available at:

http://www.cfr.org/united-states/conversation-alan-greenspan/p37305

3. January 2016 at 22:16

[…] blog post on MoneyIllusion provides an idea of the how monetary economics […]

4. January 2016 at 00:02

Demand for paper cash, all major currencies, has been booming globally. In the United States there is more than $4,000 in circulation for every US resident. No one really knows how much is offshore.

In any event, I doubt that a no-inflation economy can survive side-by-side with legal paper cash.

People start to save in the form of cash, avoid taxes, then begin transactions in cash, to avoid taxes. As the underground economy grows, the aboveground economy must absorb increasing taxes.

If you live in a relatively high-tax developed economy, and if you believe in economic incentives, then the outcome is all but foreordained.

There are many advantages to having moderate inflation in a modern developed economy, and this is yet another one.

4. January 2016 at 00:43

“There are many advantages to having moderate inflation in a modern developed economy, and this is yet another one.”

I agree, Ben, but how do you accomplish that without hurtful toxic loans that hurt people? Better to just drop the cash from helicopters. People don’t trust bankers anymore and that also occurred in the Great Depression, bankers were vilified.

And where does the collateral for all this new money come from if there is also a shortage of bonds?

4. January 2016 at 03:58

“And yes, that means lower interest rates are contractionary, as I said in a number of recent posts.”

Fun, I’ve been thinking/alluding to that since I’ve been here. My reasoning is a bit different though.

“Here’s a graph showing the relationship between the demand for currency (as a share of GDP) and T-bill yields:”

Very interesting graph, puzzles me a bit (ok more than a bit), just eyeballing it you can see it is clearly positively correlated, but why then are the second derivative speeds completely in opposition with one another…. As said by the great philosopher Arsenio Hall… “things that make you go hmmm..”

4. January 2016 at 05:06

Gary–

I prefer FICA tax holidays, financed by quantitative easing. That is, the Fed buys Treasuries and places them into the Social Security and Medicare trust funds.

A couple trillion over two years might work…

4. January 2016 at 05:55

John, You said:

“Us Keynesians would say the distortion is the result of the ZLB.”

The difference between the two graphs is bank reserves, and there is no zero lower bound on bank reserves. Negative interest is possible. If the government wants to make the base 99% cash, it can do so.

Having said that, your claim that base demand soars at zero rates supports my general model, doesn’t it?

You said:

“In other words, equilibria in economics are the result of the intersection of supply and demand curves.”

No, that’s not at all what I’m claiming. Both ideas discussed are about money neutrality/non-neutrality. That dichotomy doesn’t apply with flexible wages and prices, but the supply and demand model obviously does still apply with flexible prices. This isn’t about not reasoning from a price change.

You said:

“The thing that you and I disagree about is whether or not every recession is caused by money demand shocks.:

That’s not my claim. Most are. The 1920-21 recession was obviously caused by a money supply shock, as was 1929-30. The first 5 months of the 2008 recession was caused by a money supply shock.

jknarr, You seem to assume they have one more policy instrument then they actually have. To raise rates to 5% they’d have to sharply cut M, or raise IOR, both of which are highly contractionary.

Orn, No one really knows how much is held overseas, but even foreign holdings are sensitive to interest rates. And demand for euro currency has also been rising sharply, so this is not a substitution out of an unpopular euro. People could hold German bonds, but they have even lower yields than T-bonds.

derivs, Cash is a “stock” asset, and cash holdings in the underground economy are difficult and costly to adjust, so the response is spread out over time.

4. January 2016 at 06:31

“derivs, Cash is a “stock” asset, and cash holdings in the underground economy are difficult and costly to adjust, so the response is spread out over time.”

I think I can get half way there.. Ignore everything to the left of 1970ish since the economy was very different back then as related to credit. Then>>> Rising rates leave certain participants unable to transact ‘purely’ based on economics because they simply can’t transact on what is not supposed to exist. So therefore sensitivity is severely muted to extreme up moves in i.

When rates are rising, people who have nothing to hide will react ‘purely’ economically, so the market change that one would expect to see would be more highly correlated with extreme down movements in i (2010-present). ?????????

That makes sense to me…

4. January 2016 at 06:32

“When rates are rising, people…”

I meant dropping….

4. January 2016 at 06:52

Firstly, I certainly agree that higher interest rates increases the opportunity cost of holding cash, and will hasten the rate at which people transform their cash into bank deposits as could be seen up until 1980s. The problem is, bank deposits are in fact a superior substitute good *for all levels of nominal interest rates except when they are negative*.

Just think about it, there’s a few hypothetical reasons people will hold cash, but overwhelmingly it’s for two reasons: in the very short term to facilitate spending, and in the longer term as savings. Do you honestly know a single person, even at today’s extremely low interest rates, that actually holds their savings as cash? For 99.99% of people (except the highly paranoid and drug dealers), they hold their non invested savings as bank balances – because it’s a superior substitute good to cash, as it pays interest (even if its a tiny amount), is far safer, can be accessed from almost anywhere and can be transferred electronically from almost anywhere also.

As for consumption, higher expected interest rates actually RAISE the opportunity cost of consumption versus bank deposits, as well as investment into risk assets/ventures (forgone future interest earnings/future discounting etc). So for bank deposits, the reverse is true for money demand, higher expected interest rates will raise the demand for bank deposits and lower the desire to spend their deposits, or for those indebted – lower the demand for credit/overdraft.

This might help explain why currency levels increased again as interest rates started to fall from the eighties. It wasn’t due to a sudden desire of people to hold their *savings* as cash (because remember, bank deposits remain a superior instrument for savings even for low interest rates), it was because *consumption started increasing* – since some amount of consumption always requires cash payments, this necessarily means the level of cash withdrawals will increase also.

‘Currency hoarding’ is an archaic concept, it simply doesn’t apply for 99% of people anymore – what’s more common is bank deposit hoarding, and higher rates make deposits more appealing.

4. January 2016 at 07:01

1. I think the actual answer to this sort of comments is “of course, I don’t expect people to rush to their ATMs, but I just need them to slightly change their behaviour on the margin over a long time period for the policy to have a macroeconomic impact.”

2. @britonomist: many people in the PIGS do hold large sums of money in cash, sometimes they even hold them in bank safes! Will you argue that a Greek bank is safer and more liquid than a bank safe with large amounts of cash?

3. Drug dealing is, of course, a cash business. But so are many legitimate businesses (mostly for tax avoidance). In particular, construction and related is often a cash business and large sums are paid in cash.

4. January 2016 at 07:07

“2. @britonomist: many people in the PIGS do hold large sums of money in cash, sometimes they even hold them in bank safes! Will you argue that a Greek bank is safer and more liquid than a bank safe with large amounts of cash?”

Sure, but I assumed we were narrowing our analysis to the US in this case.

” In particular, construction and related is often a cash business and large sums are paid in cash.”

Right, but this goes back to my point about cash as a consumption aid rather than a savings vehicle.

4. January 2016 at 07:42

“Interest rates are the opportunity cost of holding cash. If you lower interest rates, people will choose to hold more cash. And yes, that means lower interest rates are contractionary, ‘

Assume the base is fixed and we start in equilibrium , then if nothing else changes its impossible to lower interest rates without the demand to hold base money by banks and indivuals exceeding the demand.

So if the base is fixed and rates fall then the demand to hold base money must have declined.

But most recession are associated with the demand for money increasing. When the demand for money increases in a sticky price world the CB can avoid recessions by increasing the supply of money to match the increased demand, which may lower rates in the short run. If the CB fails to fully accommodate the increase in demand the economy may see both lower rates and a recession.

The increase in demand to hold money may well be caused by pessimism about the future which will likely also cause a decline in people’s desire to invest and a lowering of the natural rate of interest.

Is it this decline in the natural rate before and during recessions that Scott is associating with lower rates being contractionary ?

4. January 2016 at 08:47

Britonomist, currency is a (senior) claim on the central bank, while demand deposits are claims on commercial banks. As such, demand deposits are subordinated assets – they have some degree of credit risk that currency does not have. Are there such things as bank runs and currency withdrawal limits in this world? These are incredibly significant, not some vague idea of convenience — currency is senior, demand deposits are subordinated derivatives. Not even to mention the fees associated with demand deposits — do you even bank, BritM? Northern Rock queue much?

Orn, yes, much currency resides abroad — *where there are no money-laundering-bank-reporting-if-you-are-transacting-cash-in-any-inflation-adjusted-volume-you-must-clearly-be-a-criminal-terrorist-or-drug-dealer-presumptions* In the US, currency is quasi-criminalized, with a presumption of guilt. This is a cost to holding and transacting in currency. Higher domestic costs drive currency supply abroad, where there are no such restrictions. It’s not just a demand-pull issue.

Re rates and currency demand, currency creation-and-destruction is a very important feature to the nominal economy. Currency is most associated with NGDP, while reserves are most associated with interest rates in the banking system: that’s their exclusive nexus.

At high rates, NGDP is running hot, and so currency needs to be re-absorbed into reserves. At high rates, parties have an incentive to deposit cash into banks, which then re-defines the currency into reserves, and the currency is shredded at the Treasury — money used in NGDP becomes scarcer, and NGDP slows and rates fall (more reserves).

Conversely, at low rates, the bank counterparty risk is usually elevated (high leverage at low rates). Also, you get paid nothing to keep your asset in a derivative subordinated instrument. Withdraw currency, circulate in nominal economy — reserves shrink, rates rise, NGDP expands.

My thesis is that statutory laws are interfering grossly with the normal functioning of the monetary base. The inhalation and exhalation of currency *is* the nexus of banks and NGDP.

In short, the cure to slow-NGDP woes is to let currency production rip — get rid of the quasi-criminal nature of currency. Shrink QE reserves, allow more cash actually present and circulating in the nominal economy.

4. January 2016 at 08:57

“I prefer FICA tax holidays, financed by quantitative easing. That is, the Fed buys Treasuries and places them into the Social Security and Medicare trust funds.

A couple trillion over two years might work…”

Benjamin, do you have a link to that idea? I don’t quite get how that would free up bonds when there is a shortage of bonds and cash. But post a link. Thanks.

Look we have demand deflation and millenials seem wary of credit. That could slow the economy. I don’t think business appreciates how frugal the millennials really are. Plus many of them get by on meager wages. They are not in the mood for credit.

The only real solution is to continue down the dark and potentially evil road toward negative rates, or just give people money to spend.

4. January 2016 at 09:36

I invite the reader to read John Handley’s post, which clearly and accurately summarizes Sumner’s post as a Marshallian scissors supply-demand statement (LS-IM curves, which clearly are being referenced by Sumner, in particular the LM curve is related to the inverse of velocity), then Sumner’s dishonest reply to Handley, claiming Handley misunderstood him. Typical Sumner. Nobody understands our poor boy, unless it’s K. Duda promising a fat check. Sumner claims his post is about money non-neutrality, yet the LS-IM theory is concerned with real variables and is agnostic about neutrality. Sumner will claim his post is not about LS-IM, when it clearly is. Also the statement that people respond to incentives by hoarding less cash when interest rates rise (i.e., the LM curve is upward sloping) is rebutted by commentator Orn Gudmundsson Jr’s observation about the US dollars overseas which are held for non-interest reasons.

Why do I read and post here? It’s a complete waste of time. Mr. Sumner, please ban me! I’m incapable of responding to the negative incentives to stop posting here…

4. January 2016 at 10:41

@jknarr

“Britonomist, currency is a (senior) claim on the central bank, while demand deposits are claims on commercial banks. As such, demand deposits are subordinated assets – they have some degree of credit risk that currency does not have.”

The risk is negligible, especially if you have less than 50k or so in savings.

Deposits might be *legally* ‘subordinate’, but from the point of view of your average consumer, still superior and more convenient.

“Are there such things as bank runs and currency withdrawal limits in this world?”

It’s possible, but those are extreme outlier events in a modern rich western economy.

“Not even to mention the fees associated with demand deposits”

Again, negligible.

“Northern Rock queue much?”

Northern Rock was an exceptional situation, and was the UK’s first bank run in 150 years. The run had nothing to do with low interest rates incidentally.

4. January 2016 at 11:14

Britonomist, you confuse circulation convenience with superiority. Consider Gresham: bad money circulates, good money is hoarded. Demand deposits are structurally worse off (counterparty risk, zero interest, and a raft of fees, taxes, and mounting privacy problems) than currency. Re the public, if you don’t know who’s the fish at the table, you are.

You are also willfully ignoring the new and expanding statutory restrictions on currency across the EU — all modern and rich, eh? — France, Spain, Greece… 1,000 EUR limit for transacting, 10,000 in a month for withdrawals, and that’s not Greece’s 60EUR:

To whit, your demand deposit “convenience” is simply the result of statutory punishments for currency usage!

Speaking of modern rich western currency, people were similarly forced to use Assignats (inferior money) by way of the guillotine. Did that boost the intrinsic convenience and superiority of Assignats?

Repeating extreme outlier, exceptional, and negligible is not much of an argument. Obviously, when things work well, things work well — but, at zero rates, things are not working well. Zero interest rates just *coincidentally* went alongside the biggest bank stresses of the 1930’s and 00’s? Wrong.

4. January 2016 at 11:50

Not really related, but I have finally written the definitive post showing the EZ crisis was caused by supply, not, as Sumner claims, demand shocks:

https://againstjebelallawz.wordpress.com/2016/01/03/europe-the-real-problem-is-real/

Sumner really needs to read this.

4. January 2016 at 12:59

Britonomist, You said:

“Just think about it, there’s a few hypothetical reasons people will hold cash, but overwhelmingly it’s for two reasons: in the very short term to facilitate spending, and in the longer term as savings. Do you honestly know a single person, even at today’s extremely low interest rates, that actually holds their savings as cash?”

I did my PhD dissertation on currency hoarding, and I can assure you that the vast majority of currency is held for saving purposes, not transactions. The vast majority is $100 bills, held to hide wealth from the government. So I completely disagree with your comment. There a big literature on currency held for purposes of saving, including studies by the Fed. You are simply wrong.

And yes, I’ve known people who hold large amounts of cash.

Market, You said:

“Assume the base is fixed and we start in equilibrium , then if nothing else changes its impossible to lower interest rates without the demand to hold base money by banks and individuals exceeding the demand.”

Of course. If nothing changes then nothing changes. I am assuming that something changes to cause interest rates to move, and that something is not a change in the monetary base, or in IOR (or reserve requirements). In that cause V and NGDP move in the same direction.

Ray, I’ll never ban you as long as you keep me laughing.

E. Harding. So is the argument that the collapse in eurozone NGDP didn’t cause higher unemployment because wages are incredibly flexible over there? Or is there some other argument as to why the collapse of eurozone NGDP growth didn’t cause high unemployment?

In other words, give me a tantalizing tidbit that will make me want to spend time reading your blog. What’s the elevator version as to why the NGDP shock didn’t matter?

4. January 2016 at 13:12

Heated dispute between Krugman and Timothy Taylor:

http://conversableeconomist.blogspot.com/2015/12/response-to-krugman-more-on-secular.html

4. January 2016 at 13:45

Elevator version as to why the NGDP shock wasn’t everything?

“Missing disinflation”.

My post doesn’t mention unemployment at all. It only focuses on NGDP, the GDP deflator, and RGDP. As I show in the post, the NGDP shock could have accounted for up to two-thirds of the EZ’s RGDP divergence from the United States, but no more. That’s not enough to cause the continuous decline in EZ RGDP we saw Q4 2011-Q1 2013. It’s only enough for a two-quarter recession in late 2012. And it does seem that NGDP is a better predictor of changes in unemployment in the EZ than RGDP. I guess that’s because unions are generally stronger in Europe, so wages are generally very sticky.

There wasn’t any collapse in EZ NGDP. From 2009 Q3 to 2013 Q3 NGDP declined in the EZ for exactly one quarter: 2012 Q4. There was a collapse in EZ NGDP growth, but, as I explain in my post, it’s nowhere near large enough enough to explain the collapse in RGDP (not just RGDP growth).

That enough for you?

4. January 2016 at 14:35

Stupid question: Who has the hundreds of billions of dollars in currency? I know people who say they are holding “a lot” of currency but actually are only holding a few thousand dollars. If you average that out with all of the people who barely have gross assets of $4,000 it’s tough to see who is making the decisions to hold more (or less) currency.

My first guess is that it is some sort of Pareto rule, where something like the top 20% of the holders of US currency hold 80% of the value of US currency, and probably even more concentrated than that (if 20% of the us population holds 80% of the currency, then that means they are averaging about $17K each, while the bottom 80% holding 20% of the currency is still holding over $1000 cash each, which doesn’t sound at all right). So the response function of currency to interest rates isn’t what the average Joe does to their currency holdings when rates change, but rather, what this unique subset of high-currency holders does.

The graphs are pretty convincing on their own, but it’s tough to understand the story about individual actors since I have a hard time even figuring out who those actors are (Arms dealers in Iraq? Drug dealers in Honduras? Survivalists in Idaho?).

4. January 2016 at 15:08

Arnold Kling’s new review of The Midas Paradox:

http://www.econlib.org/library/Columns/y2016/KlingSumner.html

4. January 2016 at 15:32

“I did my PhD dissertation on currency hoarding”

What period did it cover?

” I can assure you that the vast majority of currency is held for saving purposes, not transactions. ”

Netting out blatant criminals (who would be hiding their wealth *regardless* of what the interest rate is), I strongly vehemently disagree – unless the United States is a totally alien culture compared to the United Kingdom.

“The vast majority is $100 bills, held to hide wealth from the government.”

But these tax dodgers are highly unlikely to change the amount of cash they want to hoard when interest rates change, the interest income will certainly not make up for the tax expense they’d have to endure. Also ss your contention really that fluctuations in NGDP can be explained significantly by the whims of tax dodgers?

And this doesn’t address the other main problem – higher interest rates still raise the demand for bank/savings deposits/reduces the demand for credit and raises the opportunity cost of consumption/investment for everyone else not hoarding currency, having the opposite effect to hot potato for that kind of money (which is a much more significant portion of the money supply).

4. January 2016 at 17:20

“There’s a sense in which lower rates are contractionary, and another sense in which they are expansionary.”

Here’s a simple way to look at it: Take a minimal model with money, bonds, and sticky prices. There are two ways you can lower the nominal interest rate:

(1) You can raise the *current* money supply.

(2) You can lower the *future* money supply.

(1) is expansionary. (2) is contractionary.

4. January 2016 at 18:00

Scott,

“Having said that, your claim that base demand soars at zero rates supports my general model, doesn’t it?”

Yes. You’re model does not explain, however, falling velocity coinciding exactly with quantitative easing. My model, [my preferred money demand money is a cash-credit model such as https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/rhodrick/variabilityvelocity2Epdf.pdf%5D is consistent with velocity plunging when the central bank increases the monetary base while the nominal interest rate on safe assets is equal to the interest rate that money pays.

4. January 2016 at 19:19

This new post seems to reflect Morgan Warstler’s views a bit more than Prof. Sumner’s views…….

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2016/01/diane_coyle_has.html

“How We Count Counts: Diane Coyle on The Rise and Fall of American Growth”

4. January 2016 at 19:39

Scott, are you suggesting that the world economy is largely driven by drug dealers hoarding their cash???

I think a Keynesian would easily interpret this post as a dispute over the slope of the LM curve.

4. January 2016 at 20:40

Prof. Sumner,

Re: Arnold Kling, does he believe changes in monetary policy have any real effects in the short run at all? If so, does he think those effects can’t be anything more than teeny-tiny?

For some reason, your great old post entitled “Money Matters” comes to mind……

4. January 2016 at 20:51

Both Saturos just upstream of this post and Britonomist

4. January 2016 at 15:32 skewer Sumner’s theories, which contradict themselves. They either apply to the underground economy only, to criminals with negative incentives (who respond to interest rate rises even when risking confiscation of their cash if they park it at a bank) and/or perhaps only to the USA, and at best to only less than 10% of the economy (Internet: “Bills and coins now represent just 2 percent of Sweden’s economy, compared with 7.7 percent in the United States and 10 percent in the euro area”). This last point is consistent with Ben S. Bernanke’s FAVAR 2002 paper that found Fed policy shocks only changed 3.2% to 13.2% (out of 100%) of the change in any economic variable, including GDP, for the period 1959 to 2001.

In short, Sumner’s theories are only of interest to the US black economy and to drug dealers.

@E. Harding – saw your blog post and I agree; you are coming around, perhaps without even realizing it, to the view that money is largely neutral (see my comment above). Whether or not you realize this at let the biblical scales fall from your biblical eyes is another matter. I hope you do.

4. January 2016 at 21:23

I don’t think money is neutral. Indirect indicators of monetary policy tightening seem to have a powerful correlation with recessions and short-term changes in NGDP seem to have a much stronger impact on RGDP than on the price level. Money is generally neutral at high inflation rates and in the long run.

4. January 2016 at 21:37

I realized that, through the coincidence of a few haste-caused spelling and diction errors, my previous comment is pretty much impossible to understand. Here’s the intended version:

“Scott,

“Having said that, your claim that base demand soars at zero rates supports my general model, doesn’t it?”

Yes. You’re model does not explain, however, falling velocity coinciding exactly with quantitative easing. My model, [my preferred money demand model is a cash-credit model such as https://www0.gsb.columbia.edu/faculty/rhodrick/variabilityvelocity2Epdf.pdf%5D is consistent with velocity plunging when the central bank increases the monetary base while the nominal interest rate on safe assets is equal to the interest rate that money pays.

5. January 2016 at 00:48

When you attribute errors to being “on the left” you make half of us want to read you a lot less. And I say that as someone who generally can ignore your politics and enjoy the insight.

5. January 2016 at 05:15

What is the problem of holding wealth in 100 dollar bills ? One cannot assume that everyone that does that is a criminal. I personnaly dislike the idea that some government official may know everything about my financial life. And this person (the governmentn official) might be a criminal too. The vast majority of the people are not criminals. Assuming a cash economy creates criminals is not very smart, in my opinion.

5. January 2016 at 11:04

“Fluctuations in NGDP are mostly caused by changes in interest rates, which impact base velocity”

———–

As history’s greatest market timer (the Dec 2015 commodity bottom being my latest call a year ago), I will set the record straight. Low interest rates reflect no more than the supply and demand for loan-funds (not the supply and demand for money, or what the Fed should control). Thus interest rates essentially have nothing to do with gDp.

Whether short-term rates are lowered or raised (or the Fed tightens or loosens), depends on the FRB-NY’s “trading desk”, and where they are on the yield curve, and their context – primarily long-term money flows (money times velocity).

Interest rates will initially fall whenever the desk loosens, even as gDp accelerates, – if LT rates-of-change in money flows are not rising. R-gDp in this case is thus the beneficiary, rebounding first and fastest, and of course, vice versa.

To wit, the money stock can never be managed by any attempt to control the cost of credit. Keynes “liquidity preference curve” (demand for money), is patently a false doctrine.

Every recession since the GD 1.0 (literally 1942), was the Fed’s fault. Ben Bernanke should be executed for high treason for being the sole cause of the Great-Recession, GD 2.0.

And the Fed’s 2 percent inflation mandate is too high. It shouldn’t be higher than 1.5 percent. The Fed shouldn’t target N-gDp, R-gDp has to be used as its policy standard.

Michel de Notredame

5. January 2016 at 15:20

@Ray Lopez: “…only of interest to the US black economy…”

Don’t tell me: you’re a racist too?!

I didn’t realize that African-Americans have their own, separate, economy.

5. January 2016 at 16:19

“I didn’t realize that African-Americans have their own, separate, economy.”

Forgive him, he is from DC, where Marion Barry once tried to pass an amendment to make Air Jordans legal tender.

6. January 2016 at 08:47

Scott,

I’m actually mostly on your side on this one (believe it or not). But I do have one major doubt in the way you’re handling it.

How can you be sure that even a textbook rate hike (accompanied by reduction in reserves) is contractionary relative to the status quo? Wouldn’t it depend on the elasticity of velocity (or something like that)?

For example, if the Fed raises rates from (say) 4% to 5% and it does so by reducing the monetary base by (say) 2.3%, then to know the impact on NGDP, wouldn’t you need to pit the two forces against each other to see which dominates? Isn’t it conceivable that the point rate hike causes velocity to increase by more than 2.3%, and thus the smaller base is still generating more NGDP?

And then, it seems to me that it should be a no brainer that IOR is expansionary, since it doesn’t reduce the monetary base and increases interest rates. If you want to make an argument about fractional reserve banking and how a hike via IOR reduces M1 and the other broader aggregates, OK that at least makes sense, but I haven’t seen you make that argument.

Do you understand my confusion? I hope I’m at least making sense.

6. January 2016 at 09:17

E. Harding, I don’t have any big problem with the claim that 2/3 of the difference in RGDP is due to NGDP, and 1/3 due to structural (supply-side) factors.

Njnnja, The currency is mostly $100 bills, and is held by a relatively small share of households. In my view it is mostly to hide wealth form the government, or one’s spouse. I think the biggest holders are small businesses that have underreported income to the IRS.

Britonomist, The data strongly suggests you are wrong, even for the UK. ( I seem to recall that they have less currency hoarding than the US, but still have a substantial amount.) In the US, the ratio of tax rates to interest rates tells you how many years you can profitable hoard cash before you would have been better off simply paying your taxes. That ratio is correlated with the C/GDP ratio.

The theory predicts this correlation, and the data confirm it. Not sure what more you need. Are you surprised that people aren’t telling you that they hide cash to cheat on their taxes?

My dissertation was in 1984, but the recent data is consistent with what I found.

You said:

“And this doesn’t address the other main problem – higher interest rates still raise the demand for bank/savings deposits/reduces the demand for credit and raises the opportunity cost of consumption/investment for everyone else not hoarding currency, having the opposite effect to hot potato for that kind of money (which is a much more significant portion of the money supply).”

The data and theory say you are wrong. There is a vast literature on the demand for bank accounts, and all studies I know of predict that higher interest rates reduce the demand for bank accounts. That’s monetary economics 101. Read something like Laidler’s “The Demand for Money.”

Jonathan, Good point.

John, In the 1960s and 1970s V rose as the money growth rate accelerated. I think my market monetarist framework is more general, able to explain a wider variety of episodes.

Saturos, You said:

“Scott, are you suggesting that the world economy is largely driven by drug dealers hoarding their cash???

I think a Keynesian would easily interpret this post as a dispute over the slope of the LM curve.”

The interaction of demand for cash (of which drug dealers are a small share) and the supply of cash does drive the NGDP of the US, and the world. Yes.

The IS-LM framework confuses the issue more than it clarifies. It’s not enough to talk about slopes, you have to consider how one curve can shift the other. Thus a shift in the LM curve can cause an even bigger shift in the IS curve, causing rates to move in a “perverse” manner.

TravisV, Thanks, I will have some comments at some point.

Mark, Fair point, I’ll try to remember to avoid that. Of course I’m also critical of the right.

6. January 2016 at 09:30

Dr. Sumner,

I think the title of the post should be “Yes, interest rates really do impact the QUANTITY DEMANDED for money”

🙂

6. January 2016 at 11:22

Bob, Good question, and I can’t answer that. But I will say the following:

1. We know that more money means more NGDP in the long run, as there is no long run effect on interest rates.

2. We know that higher expected future NGDP causes higher current NGDP, by raising velocity.

Can the fall in short term rates due to the liquidity effect offset this? I doubt it, but I don’t know how to prove it mathematically. It’s probably an easy proof, but I’m 60 years old and having a brain freeze.

tesc, I was thinking in terms of the demand for money as a function of the value of money (1/P) in which case it shifts the entire curve.

6. January 2016 at 12:19

“Britonomist, The data strongly suggests you are wrong, even for the UK. ”

Not the data you’ve presented so far, my theory explains the data just as well as yours.

“In the US, the ratio of tax rates to interest rates tells you how many years you can profitable hoard cash before you would have been better off simply paying your taxes. That ratio is correlated with the C/GDP ratio.”

Can you expand on this? Are you talking in terms of compounded interest rates over a long horizon eventually offsetting the tax expense? But are you taking into account future discounting in this case?

” Are you surprised that people aren’t telling you that they hide cash to cheat on their taxes?”

No but I think this behaviour is highly inelastic in response to interest rate changes, and that while there might be a significant amount of this – it’s still far too small a proportion to have any powerful explanatory power compared to every ordinary tax payer with bank accounts, your own data shows that we’re talking about less than 0.1% of GDP here.

“The data and theory say you are wrong.”

Data I addressed above. As for theory, let’s be clear, *a* theory may say I’m wrong, but it’s definitely not the theory taught out of textbooks or university, take it from a semi-recent post-graduate. This is highly unconventional theory.

“There is a vast literature on the demand for bank accounts, and all studies I know of predict that higher interest rates reduce the demand for bank accounts.”

How can that be true? That would go against marginal utility theory – it would basically violate rationality. Why would people take more money out of their bank account if they are earning more interest on it? And I thought you said the demand for cash is *inversely* proportional to interest rates, that means people would withdraw more cash from their account when interest rates go down, not up.

The only explanation I can think of is what I was saying before, where you’re using an inappropriate model which considers the return on capital investment as ‘the interest rate’ (in which case a higher return might reduce the demand for savings deposits in exchange for shares, corporate bonds and capital), rather than the interest rate on safe assets like government bonds and the deposit rate. It’s absolutely vital any theory distinguishes between the two or the theory is completely useless, and is engaging in the kind of ‘mathiness’ that Paul Romer talks about using ill-defined variables.

“Read something like Laidler’s “The Demand for Money.””

Got something shorter?

6. January 2016 at 12:24

Just noticed I read the graph wrong, I was reading the left axis in percentage terms. Also I’d like to know if that data includes currency used overseas, which is a separate issue.

6. January 2016 at 12:27

In fact as the NY Fed points out: https://www.newyorkfed.org/aboutthefed/fedpoint/fed01.html

“The amount of cash in circulation has risen rapidly in recent decades and much of the increase has been caused by demand from abroad. The Federal Reserve estimates that the majority of the cash in circulation today is outside the United States.”

6. January 2016 at 12:54

One last thing, I should expand on my point regarding demand for deposits – theory might also suggest demand for bank deposits reduce with higher interest rates because it’s including credit/deposits made with borrowing under its measure of deposits – but of course I’ve already mentioned that it would reduce credit/overdraft, which is of course contractionary and proves my point.

6. January 2016 at 13:47

@ssumner

-Well, good thing we’re agreed on the European question.

And this is what the Real GDPs of the EZ, the U.S., and Japan would have looked like were they persistently at full employment:

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=33kA

6. January 2016 at 13:48

*Obviously, not entirely agreed, e.g., on the roles of specific central bankers.

6. January 2016 at 20:40

“The IS-LM framework confuses the issue more than it clarifies. It’s not enough to talk about slopes, you have to consider how one curve can shift the other. Thus a shift in the LM curve can cause an even bigger shift in the IS curve, causing rates to move in a “perverse” manner.”

I want a Nick Rowe post on this.

7. January 2016 at 05:26

I think your currency driven approach would be the most reasonable framing if currency were exogenous.

But it is not.

Low interest rates cause high currency demand, and so given the quantity of currency and higher value of currency is fine in theory, but _given the quantity of currency_ is just not very applicable to real world monetary regimes.

It certainly is not with an interest targeting central bank–which is a pretty typical regime.

The demand for monetary liabilities more generally is interest elastic in the short run but interest inelastic in the long run. This is probably because the nominal interest rates paid on many of these deposits are sticky. If more of them were more flexible, then it is likely that this short run effect would disappear. (The older studies used data from when there were few types of monetary liabilities and they were subject to regulation Q.)

The theory is that the opportunity cost of holding money is the difference nominal interest rate paid on money and the nominal interest rate that can be earned on other assets. That difference depends on the level of interest rates if the interest rate paid on money is sticky.

With the kind of privatized monetary regime I favor, your framework would not apply. No doubt that is why I am sensitive to how it is regime dependent, but the current regime makes it unhelpful as well.

More importantly, if there is a strong commitment to the level of nominal GDP, the nominal quantity of money is endogenous and so analysis about what happens with a given quantity of currency is not very helpful.

7. January 2016 at 12:30

Britonomist, You said:

“Not the data you’ve presented so far, my theory explains the data just as well as yours.”

Sorry, but you haven’t even begun to address the data I have provided. And you claims about the demand for the broader aggregates conflicts with 50 years of research in monetary economics. I suggest you read Laidler’s “The Demand for Money.”

You said:

“No but I think this behaviour is highly inelastic in response to interest rate changes, and that while there might be a significant amount of this – it’s still far too small a proportion to have any powerful explanatory power compared to every ordinary tax payer with bank accounts, your own data shows that we’re talking about less than 0.1% of GDP here.”

There are literally dozens of demand for money studies that suggest you are wrong, particularly in the long run. In the short run demand is somewhat inelastic, but not totally.

You said:

“Got something shorter?”

I don’t have time to teach you money 101. Read one of the hundreds of papers published on the subject of the demand for money. It’s mind-boggling to me that you could have gotten a degree in economics without being made aware of the most basic facts about money demand. What the hell are they teaching these days? And Laidler’s book is not very long. Don’t instructors cover this anymore?

On the new currency, yes lots of it has gone overseas, which is no big surprise given that many estimate roughly half of all US currency is held overseas. But it’s a global issue, so pointing to overseas demand changes nothing.

Saturos, Nick’s done many posts on this.

Bill, You said:

“I think your currency driven approach would be the most reasonable framing if currency were exogenous.

But it is not.”

I think you missed the point. I’m not trying to “frame” this to imply currency is exogenous, obviously it isn’t. I’m just pointing out that ceteris paribus (holding the currency stock fixed) lower rates are contractionary. And they are.

And in my example no interest is paid on money.

7. January 2016 at 16:36

“Sorry, but you haven’t even begun to address the data I have provided.”

Yes I have, but let me clarify: higher interest rates certainly increased the opportunity of cash leading up to the eighties, so this combined with other factors would have lead to reduced cash holdings, which explains the initial reduction until the mid eighties. Then, the invention of the ATM made withdrawing cash much easier and more convenient. This, combined with the continually lowering interest rates leading to more consumption would once again raise the demand for cash up into the nineties. Finally, surging oversees demand can explain the most recent surge in cash demand. That explains the data.

And yes, foreign demand changes EVERYTHING – now we have to move from a closed economy model to an open economy which introduces more variables and makes things more complex, and we now have far more questions than answers. For instance, presumably they’re using the dollar as a substitute for their own poor currency – would higher interest rates in any way make the dollar a poorer substitute good for their own currency? Highly unlikely. It’s also hard to assess the stimulative effect of less foreign demand for cash dollars. How much money, if any, do these people spend in the US economy?

Finally, I’d like to see what other market monetarists think of this – again NGDP fluctuations being beholden to the whims of foreign cash holders sounds utterly ridiculous.

“I don’t have time to teach you money 101.”

You don’t need to, for I’ve already been taught it.

” It’s mind-boggling to me that you could have gotten a degree in economics without being made aware of the most basic facts about money demand.”

Try masters degree – and incidentally my thesis (for which I got a distinction) was on banking and credit, so I believe I am well qualified to talk about money.

“Don’t instructors cover this anymore?”

Laidler isn’t covered at all.

You need to give me something better than that – you can’t just say something extremely counter intuitive regarding bank deposits (remember the entire purpose of deposit rates is to entice people to deposit more money), not explain the reason why and then just be vague and say ‘it’s covered in hundreds of studies’ which you haven’t cited, other than one 700 page book. I at least gave you a page number out of the book I cited.

7. January 2016 at 16:47

I’d just like to point out that the Bank of England apparently fails ‘money 101’ according to Sumner:

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/monetarypolicy/pages/how.aspx

7. January 2016 at 18:52

Britonomist, This is getting ridiculous. Get Mishkin’s money textbook—the number one money textbook in America

Go to the chapter entitled The Demand for Money.

Read it.

7. January 2016 at 19:06

If it’s so obvious that higher interest rates reduces the demand for bank accounts ceterus paribus (or put another way, savers don’t like earning risk free money), with ‘hundreds’ of studies supporting the notion, then you should be able to cite a specific paper or explain in detail rather than force me to buy an expensive textbook.

7. January 2016 at 19:14

Add Investopedia to the list of organizations that fail ‘money 101’:

http://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/043015/what-economic-factors-affect-savings-account-rates.asp

When banks want extra deposits, they can raise the interest rate offered on savings accounts to attract extra cash. If they want to decrease bank debits, they can lower interest rates.

8. January 2016 at 02:07

Scott, why does your graph not show currency relative to *money* ?

You say that when interest rates fall, currency holdings rise. To my mind “currency holdings rise” is the same as “we hold more of our money as cash”. To look at “holding more of our money as cash” the graph would have to show currency relative to M1 or some broader money.

8. January 2016 at 17:48

Britonomist, You said:

“When banks want extra deposits, they can raise the interest rate offered on savings accounts to attract extra cash. If they want to decrease bank debits, they can lower interest rates.”

Which supports my point. The interest rates I am talking about are market rates. Rates on deposits are lower than market rates. Let’s say they are 90% of market rates. Then the higher the market rate, the bigger the gap between deposit rates and market rates.

I just gave you the number one money textbook in America. If you don’t like that, try the number two or the number 3. Do you seriously think they are all wrong?

Keynes also made this assumption in the General Theory. Is he also wrong?

Arthurian, I use currency to NGDP, because I’m interested in explaining changes in NGDP, not the broader aggregates.

8. January 2016 at 19:00

“Britonomist, You said:”

I didn’t say that, I was just quoting from investopedia (forgot the quote marks).

“The interest rates I am talking about are market rates. Rates on deposits are lower than market rates. ”

Vague, what do you mean by market rates? That could refer to a number of things.

“I just gave you the number one money textbook in America. If you don’t like that, try the number two or the number 3. Do you seriously think they are all wrong?”

No, but perhaps I’m misunderstanding your point. For simplicity, your typical textbook economic model assumes deposit/savings account interest rates roughly track the interest rate by the central bank. Is your contention that these rates are actually invariant to each other? I was assuming you literally thought higher deposit rates do not encourage more debits. For the record I’m fairly sure savings deposit rates do roughly track the federal funds rate, but this is likely much more on the downside than on the upside.

Of course this still doesn’t address the credit side of the equation, where the federal funds rate certainly sets a floor on borrowing rates. And you’d be hard pressed to argue that deleveraging and less credit/borrowing is expansionary.

9. January 2016 at 13:42

“Today’s currency demand is about 40% larger than it would be had interest rates stayed at the levels of 2007.”

That statement is either false or completely useless.

It is false if you are suggesting interest rates caused

the increase demand for cash. If you mean the demand for cash was part of the cause behind low interest rates the Fed is already well aware of that.

The fact is the demand for cash is what forced the Fed into its huge asset purchases. After 2008, the banking system was in the same mess that the US banking system was in from 1929-1933, Bank loans collapsed and the public’s demand for cash shot up. This time the Fed’s asset purchases prevented the collapse in bank deposits.

The Fed was forced into low interest rates since there is no magical way for the Fed to convince sellers to sell securities below cost.

After 2008, had the Fed tried to do what it did after the 1929 debacle the result would have likely been the same or more likely, much worse. It is likely huge portion of the bank deposits would have been wiped out. And the demand for cash would have grown even greater. By 1933, the ratio of currency to GDP had grown a lot more than 40%. That ratio had grown by closer to 400%. But hey! the good news was the Fed held fast and didn’t drop their interest rates to zero.

9. January 2016 at 16:59

Britonomist, The standard assumption is that money pays no interest, or a lower interest rate than other assets. Indeed as far as I know that’s a universal assumption in monetary economics. It’s why the demand for money slopes downward, as a function of the interest rates. Do you see any upward sloping demand curves?

https://www.google.com/search?q=money+supply+and+demand+graph&biw=2047&bih=993&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjW8ZKNhZ7KAhVJ8z4KHUtmBwYQ_AUIBigB

Jim, You said:

“It is false if you are suggesting interest rates caused

the increase demand for cash.”

That’s exactly what I’m suggesting. Monetary economics, 101

9. January 2016 at 20:24

Okay so I see the problem; the way I was taught is that in these models money in savings accounts are not counted as part of this ‘money’. Savings accounts are less liquid than current accounts and cash – so more demand for these accounts = ‘less demand for money’ and vice versa.

A simple flow of funds type model is then assumed to match these increased illiquid savings deposits to loans for investment. But you must surely be aware of how hugely critical many economists are of this kind of flow of funds assumption, especially when the interest rate is exogenously increased (rather than increased from an increased demand to borrow) right?

We shouldn’t be focusing on such simplistic models, in the real world an exogenous raise in interest rates will cause people to want to part with their liquidity (what you might call a ‘hot potato’ effect), but they can do this by buying safe treasury bonds or putting their money in savings accounts. This however would not lead to a corresponding rise in loans for investment – indeed the rise in exogenous interest rates set by the central bank would choke off credit and investment (for the various reasons I’ve stated numerous times). And before anyone says “but savings = investment”, I’ve already explained how this identity can be maintained in this situation and I direct you to Simon Wren-Lewis’ post on that.

10. January 2016 at 07:09

It may well be that interest rates has some small influence on the demands for cash, but the evidence suggests that is not a very significant factor in why people chose to withdraw or deposit currency from the banking system.

First of all Currency held by the public is a stock and thus can’t be equated with the demand for cash.

The “demand for cash” is a flow. In other words, what the public actually withdraws or deposits in a given period represents the net demand for that period. That is assuming (unlike Greece) the banking system is at all times capable of fulfilling the current demand.

Here is graph of the monthly demand for cash in billions.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/fredgraph.png?g=36s3

Notice the demand for cash tends to operate on a yearly cycle. Typically, there is a large demand for cash in Dec. and then demand goes negative in Jan. when more cash is deposited than withdrawn. Notice the large demand for cash in Dec 1999 and reversal of the flow in Jan 2000. That was due to the Y2K scare that turned into a false alarm. None of this has anything to do with interest rates. People withdrew more cash in anticipation there might be problems with the computerized payment system.

We see another huge increase in demand for cash starting in October of 2008 and carrying through the Following spring for pretty much the same loss of confidence in the bank payment system. For the first time in 2009 the banking system experienced a positive January demand for cash. However, by January 2010 the crises in confidence in the payment system had passed and once again the net demand for cash was back to the seasonal normal. The negative demand for cash of Jan 2010 wasn’t because interest rates had gone up.

10. January 2016 at 12:55

Britonomist, This will be my last comment here, as the post is getting old. You said:

“We shouldn’t be focusing on such simplistic models, in the real world an exogenous raise in interest rates will cause people to want to part with their liquidity (what you might call a ‘hot potato’ effect), but they can do this by buying safe treasury bonds or putting their money in savings accounts.”

If the public reduces their holding of base money as a share of income, and if the Fed holds the supply of base money constant, then national income will rise.

BTW, I don’t use a “flow of funds” model, whatever that is.

Jim, You said:

“It may well be that interest rates has some small influence on the demands for cash, but the evidence suggests that is not a very significant factor in why people chose to withdraw or deposit currency from the banking system.”

What evidence? Long run or short run? Are you relying on the 100s of studies of the interest elasticity of money demand, or just looking at some graphs?

You said:

“First of all Currency held by the public is a stock and thus can’t be equated with the demand for cash.

The “demand for cash” is a flow.”

No it isn’t, read any money 101 textbook.

I did my dissertation on currency demand, I don’t need someone telling me that it’s seasonal, as are most macro variables.

10. January 2016 at 15:59

I thought you established it was about short run responses to interest rates because the discussion started with:

“Lowering interest rates won’t cause people to rush to their bank account to withdraw money.”

And you rebuffed that with

“Classic error….”

The fact is the short run responses seen in the demand for currency are not related to interest rates. That is very clear from looking at the data.

Now if you are saying that had interest rates stayed at 1980 levels there would have been less currency in circulation today, I would agree. I would also add that is about as useless as contemplating what would happen if pigs were to fly.

I find this short U-tube video to be instructive on the modern world view of using cash.