Will the Fed undershoot its inflation target?

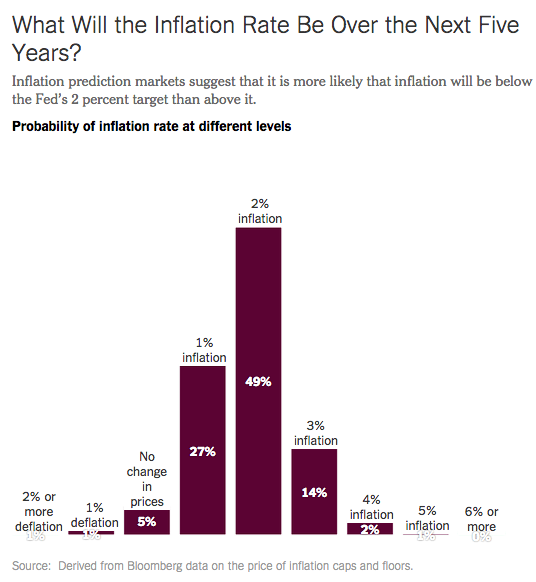

Justin Wolfers has a good piece in the NYT, with a graph showing the current values of some inflation derivatives:

The numbers actually represent ranges. Thus the 49% chance of 2% inflation means that there is a roughly 49% chance of inflation between 1.5% and 2.5%.

The numbers actually represent ranges. Thus the 49% chance of 2% inflation means that there is a roughly 49% chance of inflation between 1.5% and 2.5%.

If we assume a bell-shaped distribution, I’d guess the median inflation estimate is around 1.75% or a bit more. In that case there’s roughly a 66% chance that inflation will undershoot 2% over the next 5 years. But keep in mind that this is a CPI inflation prediction market. And the Fed actually targets PCE inflation, which runs about 0.35% below CPI inflation. So the market currently expects about 1.4% PCE inflation over the next 5 years. Alternatively, there is an 80% chance that inflation will undershoot the Fed’s PCE target over the next 5 years.

Does that mean money is too tight? Not necessarily, as the Fed has a dual mandate, and employment is likely to be above average over the next 5 years (albeit only because the previous 6 were so horrible.) Nonetheless, I’d guess that dual mandate considerations would call for no less than about 1.8% PCE inflation over the next 5 years.

Even worse, the dual mandate defense of the Fed implies they should have had inflation run above target during the high unemployment years, and of course they’ve done exactly the opposite. So if you take the Fed’s unwillingness to run a countercyclical inflation rate into account, the current situation is even more indefensible.

Even worse, the Fed seems unaware of the fact that the current policy regime is broken, and needs to be replaced before we again slide to zero interest rates in the next recession. Reading the 2009 transcripts, (which just came out) was a sobering experience. The Fed pats itself on the back when it produces stable NGDP growth (as in the Great Moderation), or 2% inflation since 1990. But when they screw up and produce a macroeconomic disaster, they discuss the situation as if it’s not their job to steer the nominal economy. Bad things just sort of happened. It reminds me of the transcripts from late 1937, when the Fed was unwilling to accept the fact that the higher reserve requirements (which raised interest rates by 25 basis points) contributed to the double dip depression, even though the policy was enacted to prevent inflation, and that can only be done by restraining AD. (BTW, I’ve complained about this asymmetry for years, as has Christy Romer, and as did Milton Friedman many decades ago.)

I haven’t even come close to reading all the minutes; if any of you have more time than I do see if there is any soul searching about the foolish decision to not cut interest rates in the meeting after Lehman failed. Or regret over the decision instituting a contractionary IOR policy in October 2008. I was especially disappointed with Bernanke’s support for ending QE1 in late 2009, partly on the grounds that further purchases ran the risk of leading to excessive inflation.

Vaidas Urba directed me to this Bernanke comment from the April 2009 meeting:

The other perspective, however, which I think is very important and a number of people pointed out, is the medium-term constraints and dynamics that affect the economy. Unfortunately, our economy still has a significant number of very serious imbalances that need to be resolved before it can grow at a healthy pace. Just to list five. First, the leverage issue of both the financial and the household sectors. Second, wealth-income ratios are well below normal, and therefore more saving is needed to rebuild those ratios. Third, we have dramatic fiscal imbalances, which have to be reconciled at some point. Fourth, we have current account imbalances, which are at least temporarily down, but the Greenbook forecast for the medium term is that there is probably some worsening in that dimension. And fifth, as a number of people mentioned, the unemployment we are seeing is probably not mostly a temporary-layoff type of unemployment. There is a lot of reallocation going on. The financial and the construction sectors are probably not going to be as big in the future as they have been recently, so there will need to be that readjustment across sectors.

If you put all of those imbalances together and you think about what is going to support sustainable economic growth, it is a little hard to see where a robust recovery is going to come from.

How about from the Fed?

Seriously, whenever you are in a deep global slump it NEVER looks like the various components are likely to generate growth. Why would hard up people fearing job loss consume more? Who will we export too? Why would firms invest when sales are slow? That was even more true in April 1933, when FDR devalued the dollar and caused industrial production to rise by 57% in 4 months. And it was true in December 1982, right before NGDP grew at an 11% rate over 6 quarters.

In retrospect it is obvious the economy needed more NGDP in 2009, and that the Fed needed to make it happen. But they didn’t see it.

PS. Not to pick on Jeffrey Fuhrer, who is a fine economist, but this seems slightly off the mark:

The US inflation rate is about 1.5 percent a year, below the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent target. Too-low inflation, Fuhrer said, indicates that not all factories and businesses are humming, and more people are unemployed.

“It’s just a symptom of a poorly functioning economy that’s under capacity,” he said.

Here are some things to consider:

1. Fuhrer is an executive vice president and senior policy adviser to Boston Fed president Eric Rosengren.

2. The Fed is targeting inflation at 2%.

3. The Fed is very likely to raise interest rates in the near future, which (in theory) suggests that inflation is either where they want it, or a bit too high.

Instead of saying 1.5% inflation is a “symptom of a poorly functioning economy” I’d rather he say it’s a symptom of a poorly functioning monetary regime.

PPS. I was asked about slowing NGDP growth in Australia. From the NGDP numbers it seems like policy is a bit too tight, but then one must also consider distortions caused by commodity price swings. However Rajat sent me the following:

Australian workers, used to fairly solid wages rise each year for the past two decades, are faced with an economy unable to deliver the types of increases many expect.

. . .

The ABS reported that wages grew 0.6%, as expected but this left year on year growth at just 2.5% for 2014.

That’s only a slight dip on the recent 2.6% yoy growth rate but 2.5% is a fresh low for this wage price index series which dates back to 1997.

I’m reluctant to criticize the excellent RBA, but they do need to ease policy a bit.

PPPS. The Boston Globe also said this about Fuhrer:

Fuhrer, a father of three adult children, lives with his wife in a historic farmhouse in Littleton. He also participates in Revolutionary War battle reenactments as a member of the Boxborough Minutemen, where he learned to play the fife.

Don’t raise rates until you see the whites of inflation’s eyes.

Tags:

9. March 2015 at 05:47

I could not agree more.

On a side note, I think the dual-mandate is fine. In my opinion, NGDP is a pretty decent indicator of the combined state of inflation-employment. NGDPLT would certainly help achieve the dual-mandate.

9. March 2015 at 05:48

Interesting blogging. Worth noting, is that most economists every year predict that inflation and interest rates will go up. Of course, for the last 30 years the trend has been down.

That track record suggests that the Fed and market players are overestimating inflation in the months and years ahead.

Side note: I like Janet Yellen, but during the 2009 FOMC meetings she sure talks out of both sides of her mouth constantly.

9. March 2015 at 05:52

Historical question: Scott Sumner, you say you have read transcripts of Fed (FOMC?) meetings for 1937. Did you mean minutes?

9. March 2015 at 06:22

LK, Yes, it’s consistent with the dual mandate.

Ben, Transcripts, they contain the real dirt.

9. March 2015 at 06:57

Mr. Summner, I don’t know if you have that info, but it would be nice to see the history of the median of these implicit inflation expectations …

9. March 2015 at 07:35

It would be really interesting to construct a graph of market expectations of CPI inflation (TIPS spreads?) versus actual measured forward CPI, and to construct a graph of the Fed’s PCE forecasts versus actual measured forward PCE. What I think it would show is that the market can forecast but the Fed can’t, hence the need for the Fed to set up and operate prediction markets for whatever economic aggregates it cares about.

Just a thought if there are any professional economists out there with too much free time on their hands.

-Ken

Kenneth Duda

Menlo Park, CA

9. March 2015 at 08:00

Hi Scott,

This seems pretty much in line with what I’ve been saying for almost exactly a year (the original prediction was 10 March 2014):

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2015/03/the-latest-pce-inflation-numbers-are-out.html

The underlying mechanism behind the model is that essentially a given dollar is more likely to be involved in a transaction in a low growth market as an economy grows since there are more ways to make an economy with lots of low growth markets than a few high growth ones.

9. March 2015 at 09:29

Thomas Piketty; ‘My story is bunk.’;

http://piketty.pse.ens.fr/files/Piketty2015AER.pdf

‘…we have too little historical data at our disposal to be able to draw definitive judgments. On the other hand, at least we have substantially more evidence than we used to. ….

‘I do not view r > g as the only or even the primary tool for considering changes in income and wealth in the twentieth century, or for forecasting the path of inequality in the twenty-first century. ….

‘I certainly do not believe that r> g is a useful tool for the discussion of rising inequality of labor income: other mechanisms and policies are much more relevant here, e.g., supply and demand of skills and education.’

9. March 2015 at 09:43

Hi Scott,

Here are the 5-year prediction graphs shown in the same format as the NYT article:

http://informationtransfereconomics.blogspot.com/2015/03/undershooting-inflation.html

9. March 2015 at 09:56

“the medium-term”

I hate this phrase. In economics, there is a long-run and the short-run. People often make the mistake of (a) thinking of these as terms of time and (b) inferring that there must be a middle-run, and thus a middle-term. It’s a sign of journalism-level economic analysis, i.e. “What has been in the news lately?”, and often corresponds with a love of vertical short-run supply-curves, at least when it comes to monetary policy AD.

Another pet peeve-

“it is a little hard to see where a robust recovery is going to come from.”

The people who know where a robust recovery is going to come from don’t tell anyone, and make money off it.

9. March 2015 at 10:34

I agree with most of your comments about Fed policy regime in general. However, we need to be careful in interpreting the “probabilities” from inflation derivatives, which are not necessarily “physical” probabilities. Derivatives prices reflect risk premiums, not just expectations. When recovering from a demand-side recession, the long inflation position is the systematically risky one (contrary to some conventional wisdom). For example, if there is a double-dip recession, we expect both inflation and equity markets to fall. Conversely, a better than expected recovery will probably lead to higher than expected inflation and equity returns, i.e., inflation has a positive beta.

So, the negative skew of the distribution could just reflect a risk premium for deflation risk. A similar skew exists in the equity options market, where downside options are more expensive than upside options. Part of the skew is due to actual skewness in the distribution of returns, but part is just crash risk premium: compensation for the fact that equity market crashes tend to be correlated with other bad things (credit crises, unemployment, etc.)

9. March 2015 at 11:23

Good post Scott. If you haven’t focused on it, here is a quote from Yellen at the Jan 2009 policy meeting supporting your argument that the people in the economics community who were loudly worried about hyperinflation the minute the Fed became unconventional had an important, stifling impact on Fed policy:

But I also agree with your remark that a second problem has developed, and we need to address it, too. There is growing concern that the Fed is printing money with abandon to stimulate the economy, and the combination of trillion dollar deficits and trillions of dollars of money creation can have only one outcome in the long run, which is high inflation that debases the currency. Now, I think this reasoning is completely misguided, but it is out there, and I think we need to consider it because it is dangerous for our credibility as an institution…

Of course, in that same speech she also said this fairly strange thing, which can’t be blamed on the economics community:

There is a view among some economists that stating a medium-term inflation objective would go a long way toward achieving it, but I am not so confident in the power of our words. I think that the inflationary psychology that exists right now is especially delicate and doesn’t correspond well to our theoretical models. For example, my sense is that, in present circumstances, many people are really relieved by the recent fall in consumer prices, which has translated into a boost to real wages, after several years of being battered by ever-higher energy and food costs. That makes me skeptical about the desirability of right away setting a temporarily high medium-term objective for inflation.

So you don’t think that setting a higher inflation target would work because your words aren’t powerful and also you are worried that setting a higher inflation target would work but higher inflation expectations would be bad?

9. March 2015 at 11:36

BC,

I’m not sure about the risk premium argument. Risk premium, in general, is an odd thing to me. Let’s say the risk-free rate is 2%. You can have a 5% return with a 5% SD or an 8% return with a 10% SD. These two investment choices have the same Sharpe ratio, but the latter over a reasonably long time horizon far outperforms the former.

Specifically for inflation derivatives, it seems like there would be some arbitrage strategies to “create” a risk-free investment using derivatives from all possible inflation outcomes. As long as such arbitrage is possible, all derivatives will reflect the same discount rate. I’m not sure such arbitrage is possible, but it seems like it would be.

The skewness is likely better explained by the strange censored distribution of wage growth through downward nominal wage rigidity. If overall NGDP decreases or merely grows at a very slow rate, some percentage of the workforce still sees their market wage increasing. Combining the increasing market wage with stagnant, above-market wages can lead to overall wage growth even in stagnant economies. See Krugman’s post here:

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/07/09/why-are-wages-still-rising-wonkish/?_r=0

A distribution for inflation has the added complication that some inflation is from raw inputs, whose price DOES go down like oil 2008-09. A convolution of some censored labor distributions and a non-censored goods price distribution would likely lead to the skewed distribution we see for inflation.

9. March 2015 at 11:59

I guess I’d never thought of the Fed’s mandate as including a direction to keep unemployment from falling too low (at least not independent of concerns about inflation), so it was strange to me to read that some undershoot might be driven by dual mandate considerations.

I guess I always assumed the dual mandate meant the Fed should maximize employment to the extent consistent with stable growth in the price level.

9. March 2015 at 12:04

“Second, wealth-income ratios are well below normal, and therefore more saving is needed to rebuild those ratios.”

This is where these VSP-type arguments always break down for me. How can you save what you don’t earn?

9. March 2015 at 12:16

Kenneth Duda brings up two things that I have been wondering about.

Is there any research based evidence that groups are better than random chance at forecasting? We know that the average of a large number of individual estimates (or guesses) tend to be more accurate at a lots of things (weights of cows, number of jellybeans in jar, etc.) but I haven’t seen any research about the quality of group (or market) accuracy in forecasting.

I also wonder why the broader market indices like a Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index isn’t in effect a market based expectation of GDP.

9. March 2015 at 13:54

Scott, some of your readers might be interested in the latest EconTalk – Russ Roberts did a live interview with Lawrence White on monetary policy/monentary constitution:

http://www.econtalk.org/archives/2015/03/lawrence_h_whit.html

White had some favorable things to say about nominal income targeting.

9. March 2015 at 14:46

Michael Byrnes, great find thanks!

9. March 2015 at 14:47

Excellent graph from Joe Leider:

http://joeleider.com/wp-content/uploads/monetary_trend.jpg

From this post:

http://joeleider.com/economics/replacing-the-fed-with-a-computer

9. March 2015 at 15:15

The commercial banks have to have something to buy when they’re given “high powered money”. Before Bankrupt U Bernanke remunerated excess reserve balances, the CBs always bought short-term debt (money market debt), from the non-bank public in the secondary market, pending a more profitable disposition of their legal lending capacity (between 1942 and Sept 2008). I.e., they always remained fully “lent up”. This counter-cyclically increased the money stock and thus increased aggregate monetary demand as well as put a floor on interest rates.

Bankrupt U Bernanke did everything wrong. Initially, the FRB-NY’s “trading desk” bought up all the “specials” (zero-risk-weighted assets), absorbing short-term debt that the CBs otherwise would have. Later (as bidding turned negative for the first time at auctions), Bankrupt U Bernanke backtracked and initiated Operation Twist 1 ($400b), and 2 ($267b), selling short-term debt for long-term debit in September 2011 and expanding it in June 2012.

And the Fed didn’t collaborate with the Treasury on the type of debt to be issued. Effective monetary management is impossible without the co-operation of the Treasury. Not only may the Treasury exercise important monetary powers through the timing of their borrowing, but specific monetary objectives may be achieved through a choice of the types of issues to float. Within board limits the Treasury can plan on the types of securities to be sold and decide whether they should be short-term, long-term, marketable, or redeemable, eligible or ineligible for bank investment, etc. I.e., the Treasury can decide who will buy a given issue (targeting the non-bank public).

Then Bankrupt U Bernanke administered the coup de grâce, he introduced the payment of interest on excess reserves which induced dis-intermediation among just the non-banks (which comprised 83 percent of the lending market pre-Great-Recession). And he did this just as the economy was contracting.

And the counter-cyclical increase in bank capital accounts absorbed almost a trillion dollars of the money stock that was initially created – completely assinine considering the Fed’s liquidity funding facilities and TARP.

9. March 2015 at 15:21

“I think it would show is that the market can forecast”

I’ve never met a really good trader that thought a future was a prediction of future price. Just simply what it is, Fair Value of future price based on current spot price. That is why the basic formula for a future is FV = PV(1+rt). If the future has a high volatility or low volatility would express how much one would expect that price to deviate over that time frame. So only if it has a volatility of 0 would one be assuming it was a prediction. Futures are for hedging, hedging allows you to not care about where the future ends up on its expiration.

“The skewness is likely better explained by the strange censored distribution of wage growth through downward nominal wage rigidity”

Normally skewness reflects the expectation of volatility change at different price levels. Equity volatility increases significantly on down moves and therefore has a skew to the downside. Most commodities, volatility increases on the upside and therefore show positive skewness to the upside.

Scott, I also agree with how you are looking at it. It can have a 49% chance of being above or below a target, or a 49% chance of being within a certain range, but 49% chance of being a specific target would be a new one for me.

Now much more fun watching Brazil implode than talking about future predictions. Raising taxes and austerity at the same time… add in high inflation.. high interest rates.. an all too illiterate population… lots of commies.. throw in 101% of politicians being corrupt.. then shake it all about… and the fun has not even started yet!!

9. March 2015 at 15:26

QE3 was literally contractionary. The rate-of-change in monetary flows (our means-of-payment money times its transactions rate-of-turnover), the proxy for inflation, fell by 2/3 from January 2013 until December 2014. The proxy for real-output fell by 1/2 from July 2014 until December 2014.

“I was especially disappointed with Bernanke’s support for ending QE1 in late 2009”

Sumner’s right. The short-fall in the money stock stuck out like a sore thumb at that time. Bankrupt U Bernanke’s tight money policy caused the 1st qtr. of 2011 contraction in real-output.

9. March 2015 at 15:40

Securities held outright – H.4.1 (Factors affecting Reserve Balances)

07/2/2008 “” $478,838.00

08/6/2008 “” $479,291.00

09/3/2008 “” $479,701.00

10/1/2008 “” $488,541.00

11/5/2008 “” $490,027.00

12/3/2008 “” $488,445.00

01/7/2009 “” $495,383.00

02/4/2009 “” $511,440.00

03/4/2009 “” $581,721.00

04/1/2009 “” $773,497.00

QE1 didn’t reverse the roc in money flows until March 2009. Then the roc in MVt (proxy for real-output), fell below zero in the last half of 2010, and long-term money flows fell by 99 percent (God awful money management). This was a treasonous (unconscionable), act.

9. March 2015 at 15:44

And QE wasn’t an equivocal asset swap.

T-bills have a hyperactive secondary market (the largest, deepest and most liquid in the world). They are fungible (tradable), and represent the esteemed prudential reserves (money stock), of the unregulated E-D market (larger than the domestic money stock). U.S. Treasury issuance is always oversubscribed. Indeed, investors infrequently pay premiums to acquire them (accepting negative returns).

IBDDs however, are circumscribed to the member commercial bank’s interbank market (unless they are converted to cash or foreign assets). They haven’t been “hot potatoes” since they were remunerated. It would be ignorant to target the FFR when reserve velocity is non-existent and the CBs are unencumbered.

9. March 2015 at 16:35

(Last repost)

Thanks for the Oz commentary, Scott. Of course, the RBA thinks policy is already very easy and in fact that monetary policy is losing its mojo:

http://www.rba.gov.au/speeches/2015/sp-dg-2015-03-05.html

Same ol’ story I’m afraid!

9. March 2015 at 16:51

Sumner replied:

“How about from the Fed?”

“Seriously, whenever you are in a deep global slump it NEVER looks like the various components are likely to generate growth. Why would hard up people fearing job loss consume more? Who will we export too? Why would firms invest when sales are slow? That was even more true in April 1933, when FDR devalued the dollar and caused industrial production to rise by 57% in 4 months. And it was true in December 1982, right before NGDP grew at an 11% rate over 6 quarters.”

That is a misreading of what Bernanke said in that quote. Bernanke was not talking about the components of aggregate demand, such as the components you mentioned: firm domestic sales, or export sales, or consumer sales.

Bernanke there is talking about Ratios between financial and real components that are not components of AD. Higher AD cannot address these ratios. It has nothing to do with them.

Bernanke was saying that by that view he was referring to, and granted its importance, the structure of the US economy was full of imbalances. And that view is correct. Healthy economies need quite a few ratios to be balanced. Just like an individual must be balanced, so too must individuals taken together be balanced.

Higher aggregate price levels or higher aggregate NGDP cannot address these imbalances. That is your blind spot. You believe NGDP is the monolithic centralizing force that it is not. A lower monetary policy will just prolong, and in my view, and perhaps even in Bernanke’s Apr 2009 view, exacerbate those imbalances.

Those imbalances of course were largely brought about by the very prior too loose monetary policy that you wrongly believe the economy needed even more of and foolishly needs more of today as well.

Looser money in the form of credit expansion cannot address imbalances between debt and income.

Looser money in the form of credit expansion and altered interest rates cannot address imbalances between industries such as too many finance and construction jobs.

Looser money in the form of monetizing government debt cannot address fiscal profligacy.

What you are advocating right now, and what you believe the Fed should have done back in 2009, are the very causes of the imbalances the cause of which you are unable or unwilling to understand.

As of now, you do not show any understanding of the monetary transmission mechanism, of how central banks targeting aggregates nevertheless cause relative changes. Your lack of understanding this is communicated outwardly as “they are not important”. However they are important. More important than aggregates as a matter of fact, since it is FROM these relative variables that bring about, create, result in, all aggregates.

9. March 2015 at 17:57

Central banks buying government debt from member banks, and member banks retrospectively and proactively acting upon that inflation, in the long run brings about more debt, dollar for dollar, than it does “income”.

Do the math.

And you can stop acting so surprised and disappointed that the Fed works for the bankers, not you. IOR was designed to flood the banking system with new reserves so as to prevent financial system collapse, while at the same time preventing runaway price inflation throughout the broader economy.

Instead the better approach to take is to want to abolish the Fed, as Milton Friedman indicated he had long been in favor:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m6fkdagNrjI

The Fed will not abolish itself. Pragmatists who pay lip service to the benefits of abolishing it, but nevertheless spend all their days effectively praying to it, are decieving themselves, and perhaps intentionally others as well if they take Rorty seriously.

Central banks will never make all socialist minded economists happy, since it can only engage in one plan that destroys the value gaining plans of other socialist minded people. It is why socialists have to “eat” each other so that “the one true” benevolent plan can arise.

When Sumner advocates for NGDPLT, he is whether he wants to admit it or not, actually advocating for threats of violence against those who would otherwise peacefully and without any aggression against other people’s persons or property, act against it and in favor of themselves instead. He would label these people as “criminals”. First, he wants them to be sent a letter containing threats. A demand for obedience. If no obedience is had at that point, then he wants a visit by armed goons who will kidnap you, in chains, to be sent off to a building where you will likely be sexually assaulted and beaten, or worse. If you still do not obey, then you will be considered by Sumner as a violent criminal and a danger to society, in which case he wants those armed thugs to shoot at you until dead.

This is no exaggeration folks. It is not hyperbole. In order for Sumner to impose his socialist plan on society, what he labels with a lofty single word, capitalized of course (as did the Prussian monarchy court intellectual Hegelians) as “NGDPLT”, is to be aggressively, not defensively, imposed on your person and property, and if you continue to opt out and go about your business without aggressing against anyone, but only defending your person and property from aggression, then you will be murdered.

For those who wonder why I disagree with Sumner’s plan for me, that is the reason. His plan FOR ME is backed by his desire to have me killed by those in the state, the very people he often claims on this blog he dislikes. He doesn’t like anyone in Congress, he says he hates the police putting non-violent “drug criminals” in jail, and yet, and yet!, he advocates for those same people to put other non-violent “criminals”, i.e. “money criminals” in jail.

The insane asylum that is this blog I read for research purposes. I research the ideas of the insane who are walking about outside of locked buildings. The free range patients so to speak.

The non-insane are often in the minority. Think of Socrates living among those who wanted to kill him for simply disseminating philosophical ideas. I am quite far from the intelligence and wit of Socrates, but myself and those who understand themselves far better than others understand themselves, are in a similar position as he. My ideas, when put into action, do not aggress against anyone’s person or property, but nevertheless the prevailing “law of the land”, I.e. the state’s laws, which are necessary for Sumner’s socialist plan to be imposed on everyone, legalize my murder.

I hope you can understand why Sumner is on the wrong track. Anyone who advocates for aggression against others, 49% of the population if need be, but dresses it up in economic verbiage and rhetoric, is not being upfront with you, and is not offering anything other than a destructive ideology.

9. March 2015 at 19:02

@MF: “Looser money in the form of credit expansion …and altered interest rates … [and] monetizing government debt”

Odd, isn’t it, that MM recommendations don’t include any of the things you mention. They recommend (1) communication (setting a clear level target for future NGDP), and (2) expanding the monetary base via OMOs. You mention three approaches you’ve imagined for looser money, but you somehow (after all these years!) miss the actual proposals being made.

“can not address imbalances between debt and income … between industries such as too many finance and construction jobs … fiscal profligacy.”

And none of these are the goals for NGDPLT, so again you seem to have made yourself irrelevant to the discussion. (Although possibly you could try to twist the first one in there, and the last one might happen as a distant, low-priority, secondary effect.)

“the prevailing “law of the land”, I.e. the state’s laws … legalize my murder.”

Is there an ETA for this action? Soon, perhaps?

9. March 2015 at 19:45

Yeah, I never get this argument-and still don’t, honestly. LOL. I maybe feel like I follow it better than in the past but I’m still far from totally there. I do think that part of the disconnect that many people have is what ‘Saving’ means under the standard Neoclassical model.

I get it from what you’ve said before that how you-and most establishment economists-define savings and investment are different from how most people think of it.

What might help bridge the divide then would be if you could simply unpack the terms-in the interest of the understanding you’re trying to forment.

For example one thing that I’ve finally figured out is that the standard model doesn’t consider stocks as ‘investing’ but as ‘savings.’

So I don’t know if you can give a basic list of what activities count as ‘saving’ vs. ‘investment’ etc. That might be the way to get it.

9. March 2015 at 19:46

This comment was meant for the post on taxes.

10. March 2015 at 03:11

MF is quite right, Sumner is very aggressive, and masquerades as a free marketeer just because he studied at U of Chicago. Yet, like Lenin, Engels, FDR, Keynes and others, all wealthy, Sumner is in fact an enemy of the wealth creator and monied class–his aping his liberal father the older he gets, as he wrote in another post.

Even more dishonestly, Sumner has shown, in debating me, that he will stoop to nearly anything to win an argument, even violating his ‘never reason from a price change or price level’ by arguing Zimbabwe has ipso facto loose money if inflation is the teens, even if real GDP is also high. It’s the Sumner attempt to make work for economists, so only they can pronounce a ‘cure’ for an economy by reading the monetary tea leaves. Never mind that if money is superneutral, then monetary policy is a charade (a fact cited in Wikipedia, but Sumner ignores this distinction, as is typical of his debating style).

10. March 2015 at 06:00

Jose, Sorry, I don’t have that.

Ken, I think people have looked at the Fed’s forecasting ability, but I don’t recall the details. Just to be clear my biggest problem with the Fed is not their inability to forecast—I think they knew they were going to undershoot in late 2008 and 2009—but rather their unwillingness to target the forecast.

Thanks Michael, I’ll take a look.

Thanks Travis.

Derivs, I don’t think that formula applies to NGDP futures.

And I’ve been bearish on Brazil for a while, as you may have noticed.

Rajat, Thanks for the link.

Ray, You said:

“his aping his liberal father the older he gets, as he wrote in another post.”

You even got that wrong! Wow.

And Zimbabwe had inflation in the teens? Like fifteen quadrillion?

10. March 2015 at 10:25

“RBA thinks policy is already very easy and in fact that monetary policy is losing its mojo”

It takes as many morons to run central banks as it does pollocks to put in a light bulb.

10. March 2015 at 15:24

@Ray Lopez: I thought you had vowed to give up commenting here. Are you having trouble keeping your promises?

Perhaps time to repeat Student’s wonderful quote: “You should try going on a hunger strike between lunch and dinner too.”

10. March 2015 at 18:11

“Derivs, I don’t think that formula applies to NGDP futures.”

I agree, it was the concept of a Future not being a prediction but being based on a fair value based on present value that I was trying to make. I would actually go something more along the lines of a smooth spline formula but I thought writing that might be a bit much. (you can skip the following if it blurs the eyes, but please read the last paragraph as I do have a serious question)

For shits and giggles (and the fact I have way too much free time) I did build an NGDP curve based on the difference of the difference by simply butterflying the months. I made the first one coming out of a recession so I made current month NGDP 0 and made the back end 3.5% NGDP, made it rather steep acheiving 0 to 3.5 in 28 months. So to show my point. I have March (year 1) at .81%, Apr 1.16%, and May 1.475% making the fly (.81-(2*1.16)-1.475) or .036%, then make June 1.756% so the next fly is .0334% and then July 2.007% making the following fly .0309. Then if you butterfly each of those flys you would come up with a second order on every fly I am creating of .001.

Now these are fairly steep and if I wanted to lengthen the time from 0 to 3.5 I would simply make the butterflys worth less and therefore the curve would take longer to flatten. If someone bid up the front I would do the same making the flys narrower. Regardless i am never making predictions I am simply focusing on the flys in an effort to spread across the curve and remove risk should the curve flatten, invert or change shape. Once the curve went flat all months would be 3.5% and all the flys would now converge to 0.

In simpler terms. using Mar, Apr May, (.81, 1.16, 1.47) I would be trying to buy Mar.8 buy May 1.46 and sell 2 Apr at 1.17. Essentially selling a series of spreads I value at .04 for .08. The curve would have to flatten real fast to lose that way, I’d have no VAR, and a hell of a nice Sharpe Ratio if I did that over and over and over again all along the curve. I think I just built the first NGDP curve!!! Once I determined how far out it went flat, where it went flat, and had my real starting point I could move it any way I want and know it should work perfectly.

I did not put in any seasonality though, which is my real question. Does U.S. NGDP have seasonality? I never thought about this but I was reading an excellent book yesterday (between playing Marvel Lego Superheroes) “The Wages of Destruction” by Adam Tooze and he was talking about Hitlers efforts to smooth production in pre-war Germany between winter in summers in a predominantly agrarian dominated economy. Interesting thought how NGDP smoothing would work in that type of economy. My one disagreement with NGDP targeting is one you yourself have pointed out in a non diversified balance sheet economy, I wonder if the same would apply in a seasonal economy???

10. March 2015 at 20:46

@Sumner: “Ray, You said:

“his aping his liberal father the older he gets, as he wrote in another post.”

You even got that wrong! Wow.”

You said that a few years ago, remember? That the older you get the more you become like your dad. I actually read and remember your old posts, maybe you should try and do the same. That said, it’s not good as an academic and public intellectual to be consistent, as it boxes you into a corner. Look at Krugman, he repudiates his former believes all the time. And you can use that famous quote by Keynes: ‘What do you do Sir?’ as justification.

11. March 2015 at 01:16

Don Geddis:

“Odd, isn’t it, that MM recommendations don’t include any of the things you mention. They recommend (1) communication (setting a clear level target for future NGDP), and (2) expanding the monetary base via OMOs. You mention three approaches you’ve imagined for looser money, but you somehow (after all these years!) miss the actual proposals being made.”

Actually Don, MM does in fact include all of those things.

What is odd then is that me, someone who is against NGDPLT, seems to know more about it than you, a supporter of it.

Let us go through the mechanism then. You mention the Fed will “expand the base via OMOs”.

First, an OMO as presently practised is for the Fed to buy what is now a recently purchased Treasury bond from the member banks, “member” status established by acts of congress (or what I like to call “A bank being ‘made’ by the head family”), who for their part know the Fed will buy the bonds from them. In recent times the holding periods before monetization have been as little as a few days. The fact that the ‘made’ banks buy the bonds not without the intention of selling them to the Fed, and the fact that the Fed can buy effectively unlimited supply of bonds, turns the Fed into a monetizer of government debt, with the made banks playing the role of public legitimizer, or consigliarie.

Since MM advocates for the Fed to buy government bonds, and kitchen sinks if need be, MM therefore advocates for a form kf government debt monetization. The only difference between the “direct” monetization that you falsely believe totally distinguishes MM theory in quality, and the “indirect” monetization that presently takes place, is that the member banks get a cut for providing the service of brokering the government’s debt. OK, I’ll grant you it is not quite banana republic behavior. More like plantain republic behavior. I see no reason to believe it is not debt monetization simply because the made banks the congress has established, are getting a cut.

Second, you deny that MM theory promotes credit expansion. This is especially odd because it is by way of credit expansion that new money becomes the broader public’s property. It is precisely why the total money supply is always multiples of times greater than the base money supply. That difference is all credit expansion driven. Unless you are claiming a version of MM where it intends to outlaw fractional reserve banking, then what I said is accurate.

“can not address imbalances between debt and income … between industries such as too many finance and construction jobs … fiscal profligacy.”

“And none of these are the goals for NGDPLT”

I never said they were. You misunderstood. My fault on that one, because I was being witty and not explicit. What I argued in that list are all caused by what would bring about NGDPLT.

What matters is not so much the intentions you have in mind for socialist plan X, which I have learned you are all convinced is nobler than what Steve Jobs, as well as medicine producers, have done for humanity, but the results of it are what I am focused on.

You guys can only see the result of stable NGDP, whereas I also consider the real effects. The only time you touch the real effects are a negative, a void type consideration of what won’t happen. You never seriously address what will happen. That is where I contribute and become more relevant than you on this blog, because what you say here is what a dozen or so other followers say. You are not providing any food for thought here, whereas I am.

“the prevailing “law of the land”, I.e. the state’s laws … legalize my murder.”

“Is there an ETA for this action? Soon, perhaps?”

Ah, the second time you have called for my murder. You are, quite clearly, a psychopath.

Good thing you’re sitting in your parent’s basement away from society. I’ll help keep you off the streets where you could manifest your hatred of innocent people in its full glory.

But there is a cure for you, it’s philosophy. Your chosen Weltenschauung is by its nature not inclusive of all humanity. It splits society. The only way yours can be brought about without internal conflict is through extermination of dissenters.

But bad news for you, and good news for me and if communications are honest, good news for a lot of other people: I am not going away. You will continue to see my words, and quite frankly, I will enjoy seeing you squirm, that is until you learn a better philosophy than the garbage you picked up without question or analysis. Then you and I can be friends instead of you wanting me to be murdered.

11. March 2015 at 04:39

[…] one line towards the end of this Scott Sumner post. It reminded me that some months ago I had entertained the idea that the RBA was […]

11. March 2015 at 06:28

Derivs, I have no idea what you are talking about, but let me just say this. I’d be thrilled if the NGDP futures market was inefficient, so that I could easily become very rich.

Ray, You can’t still be commenting, as you said that you were going to stop. So I’ll assume you are just a ghost.

11. March 2015 at 09:03

@MF: “I see no reason to believe it is not debt monetization”

Your lack of understanding, doesn’t make something into a fact.

“you deny that MM theory promotes credit expansion”

No, you said “Looser money in the form of credit expansion“, but credit expansion is not the primary transmission mechanism for looser monetary policy. Your claim wasn’t “right” or “wrong”; it was irrelevant.

“Then you and I can be friends”

Please, no! Do I really deserve such torture and punishment?

16. March 2015 at 01:56

i’m going to have to disagree with you there on the whites of the eyes…it should be don’t raise rates until inflation is already shooting you in the back. (obviously not as nice a quote)

“Bernanke’s support for ending QE1 in late 2009, partly on the grounds that further purchases ran the risk of leading to excessive inflation.”

that really is absymal – worrying about inflation in the depths of the worst recession for eighty years.

what exactly would have happened if they overshot a bit and ran 2.5 or god forbid 3 percent inflation for a few years, would it have been impossible to constrain (given we got out of stagflation how hard would it have been to tighten)

its just incomprehensible, from an economic point of view, for them to think inflation is a problem controlling at 3 percent when they can prematurely tighten at 1.5 percent or below (whatever they were in 2009)

there must be some pretty crazy other (political?) constraints on bernanke to make comments like that – or does being around hawks just make you hawkish

truly bizarre – someone needs to come up with a good public choice/political theory of his behaviour.