Will it matter when the Fed has “traction?”

People have made all sorts of arguments against “monetary offset,” but there’s only one that actually makes much sense. The argument is that the Fed does not like doing “unconventional policies” like QE, because they feel “uncomfortable” with a large balance sheet. (Put aside the fact that QE is perfectly conventional monetary policy–open market operations—and that there is no reason at all to feel uncomfortable with a large balance sheet. The Fed is effectively part of the Federal government.)

Nonetheless, there is a sort of plausibility to the theory; Fed officials will occasionally say they would cut interest rates further if they could. But what is the implication of this theory? It seems to me that this theory implies that Fed policy should become much more aggressive when the Fed is no longer hamstrung by the zero bound. When they can stimulate without adding to the balance sheet. But this raises an interesting paradox—the Fed is conventionally viewed as being “stimulative” when they cut rates. Thus the Fed should want to cut rates as soon as they can do so, which means right after they raise them!

Of course I’m half-kidding. More realistically the implication is that once the Fed stops doing the “uncomfortable” QE, there will be a long period of zero rates before they raise them. And perhaps there will be, but right now the Fed suggests it will be raising interest rates in less than a year.

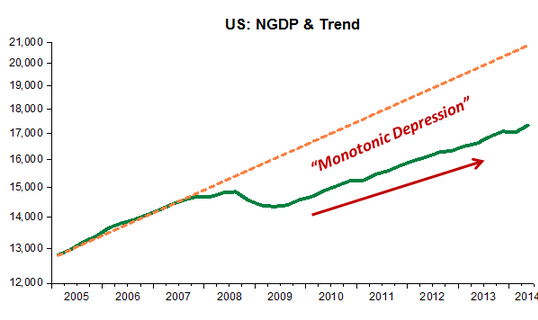

Here’s a graph from a Marcus Nunes post:

NGDP had been rising at about 5% per year in the 17 years before the recession, and it’s been rising about 4% per year in the “recovery.” Because wages and prices are flexible in the long run, the real economy has been recovering despite the lack of any demand stimulus. We have fallen from 10% to 5.9% unemployment. But most people think the economy is still in the doldrums, and needs more stimulus. President Obama just instructed the Department of Labor to increase unemployment compensation benefits (without any authorization from Congress of course–why do you think would Congress be involved in spending decisions?) This was done because unemployment is at emergency levels, requiring extra-legal remedies.

NGDP had been rising at about 5% per year in the 17 years before the recession, and it’s been rising about 4% per year in the “recovery.” Because wages and prices are flexible in the long run, the real economy has been recovering despite the lack of any demand stimulus. We have fallen from 10% to 5.9% unemployment. But most people think the economy is still in the doldrums, and needs more stimulus. President Obama just instructed the Department of Labor to increase unemployment compensation benefits (without any authorization from Congress of course–why do you think would Congress be involved in spending decisions?) This was done because unemployment is at emergency levels, requiring extra-legal remedies.

Fortunately the Fed is no longer doing the “uncomfortable” QE policy, which adds to the balance sheet. So if you believe the fiscal policy advocates, the Fed should be raring to go with stimulus. How do they do that? By promising to hold rates near zero for a really long time, or until the labor market is really strong. But instead, they are suggesting that they will probably raise interest rates soon. There will be no attempt to get back to the old trend line; the new one seems just fine.

Let’s consider an analogy. A bicycle rider has a “policy” of maintaining a steady speed of 15 miles per hour. Then he hits a long patch of ice, and slows to 10 miles per hour, perhaps due to a lack of traction, perhaps because he decided to go slower. How can we tell the reason? How about this, let’s put a strong headwind in his face, and see if the speed slows even more. But now he petals harder and keeps maintaining the 10 miles per hour speed. That suggests it’s not a lack of traction. But the pessimists insist it must be a lack of traction, why else would he have slowed right when he hit the ice? Then the bicycle final comes to the end of the ice. The lack of traction proponents expect him to suddenly speed up, exhilarated by the sudden traction of rubber on asphalt. Oddly, however, the bike keeps plodding along at 10 miles an hour. Nothing seems to have changed even though the ice patch is long past.

[In case it’s not clear, the headwinds were the 2013 austerity, and the end of the asphalt was the end of the liquidity trap.]

Here’s my claim. The Fed promise to raise rates soon is not the sort of statement you’d expect from a central bank that for the past 5 years had been frustrated by an inability to cut rates. (Nor is their other behavior consistent—such as the on and off QE.) Rather it’s the behavior of a central bank that has resigned itself to pedaling along at a slower speed. Ten miles per hour is the new normal.

I don’t want to sound dogmatic here. Obviously monetary offset is not “true” in the sense that Newton’s laws of mechanics are true; the concept only applies in certain times and places. Oh wait, that’s true of Newton’s laws too . . .

Opponents of monetary offset face two big problems. In theory, the central bank should target some sort of nominal aggregate, and offset changes in demand shocks caused by fiscal stimulus. And in practice it seems like they do, as we saw in 2013, even at the zero bound. So if monetary offset is not precisely true, surely it should be the default baseline assumption. Instead, as far as I can tell 90% of economists have never even considered the idea.

PS. Totally off topic, I love this sentence from an article on why a million dollars no longer makes you rich:

Although it sounds like a lot of cash, $1 million of today’s money is only worth $42,011.33 of 1914 dollars, which is less than today’s median household income.

Someone should collect all these amusing claims in the media. They could have added that today’s median income of $42,011 is only equal to $1764 in 1914 dollars, roughly equal to the per capita GDP (PPP) of Haiti. I guess I was wrong, the American middle class really is struggling.

Tags:

30. October 2014 at 20:28

Holy crap, that Examiner article on unemployment insurance had to be written by a 4th grader. Wow.

The good news is that there just aren’t many people unemployed for more than 26 weeks but less than 100 weeks. I wouldn’t be surprised if the proposed extension affected less than 100,000 workers, depending on how many states qualify. Probably is a decent photo op for innumerate voters & 4th graders moonlighting at the Examiner.

30. October 2014 at 20:46

Sorry, this is a random thought completely unrelated to this post. You’ve said in the past that you believe in progressive taxation for utilitarian reasons even though you believe it is worse for economic growth. But if it’s worse for growth, then doesn’t that reduce utility for an extremely large number of people in the future? Are you valuing the utility of future people far less than current people?

30. October 2014 at 21:13

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-10-31/boj-unexpectedly-boosts-easing-amid-weak-price-gains.html

BOJ announces it will expand its QE program, Nikkei rises 4.5%!

The liquidity trap theory is dead. Please please please follow in their footsteps ECB.

30. October 2014 at 21:14

There does seem to be something weird about this recovery, and I don’t think it is “insufficient demand.”

There is a lack of dynamism. There is a reluctance to take risk.

I think that the regulatory environment is partly to blame. When Ben Bernanke can’t qualify for a mortgage, money is tight.

I think that extending unemployment benefits is exactly the wrong medicine.

Regarding rates, I can’t see the Fed raising rates until 2016.

The bicycle metaphor is not working for me…

30. October 2014 at 21:17

“Let’s consider an analogy. A bicycle rider has a “policy” of maintaining a steady speed of 15 miles per hour. Then he hits a long patch of ice, and slows to 10 miles per hour, perhaps due to a lack of traction, perhaps because he decided to go slower. How can we tell the reason? How about this, let’s put a strong headwind in his face, and see if the speed slows even more. But now he petals harder and keeps maintaining the 10 miles per hour speed. That suggests it’s not a lack of traction.”

That says exactly to me lack of traction.

If he slowed more that would suggest a lack of stamina. If he maintains speed with the increased headwind, that says lack of traction.

30. October 2014 at 21:17

BOJ expands monetary base to 80T yen per year

The central bank says it will expand annual bond purchases to 80 trillion yen a year, up from the current 50 trillion yen. It will also extend the duration of bonds it holds to about 7-10 years.

The impact on markets was swift: dollar-yen jumped 1 percent to 110.26, while the Nikkei surged over 4 percent to its highest levels since September 25.

http://www.cnbc.com/id/102139427

30. October 2014 at 21:20

Also debunked is the belief that consensus is more important than policy stance. The vote was 5-4 in favor of expansion.

30. October 2014 at 21:21

I was wondering why the S&P500 futures abruptly spiked 15 points (0.75%) at 12:45am EDT. TheMoneyIllusion has the answer!

30. October 2014 at 22:41

Krugman has a new column comparing Japan with west, mentions his old advice, wanted them to do more fiscal stimulus. For anyone who can get past the paywall: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/31/opinion/paul-krugman-apologizing-to-japan.html

30. October 2014 at 22:42

Meanwhile the yen is at a 6 year low and the Nikkei just rose 4%, according to CNBC.

30. October 2014 at 23:07

Hm… Scott, I just tried to post a comment with links to my last three posts. I assume that I have run afoul of a spam filter or something.

Anyway, I would love to have you read my last 3 posts, starting with “Returns to Capital Aren’t High”. It started as a response to the recent Krugman & DeLong articles on national income shares to profits and compensation. But, as I looked at the data and worked out the response, it led to a novel realization about what is happening to compensation that relates to my recent work on risk, housing, etc.

This might get eaten if I include a link, so if you’re interested, just click on my name in your blog roll.

I’m curious what you and some of the other folks here think of it.

31. October 2014 at 01:03

I agree in general with Scott’s assertion of monetary offset, especially in the US. However, this chart [http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21627625-politicians-and-central-bankers-are-not-providing-world-inflation-it-needs-some] of central bank inflation targets got me thinking that maybe monetary offset doesn’t apply in Europe. According to the chart, the ECB’s inflation target is a broad range of 0-2%, not 1.9% as others might have thought. If the ECB really does have such a broad target, then perhaps fiscal policy can determine the actual inflation within that broad range.

Suppose a bicyclist has a policy of pedaling harder when his speed is below 10 and easing off when is speed approaches 15, allowing his speed to fluctuate between 10-15. In that case, applying headwinds and tailwinds can affect his speed. Even in this case though, I would still agree that the non-offset occurs only by central bank choice (of not having a more precise target). Which is to “blame” for the speed being below 15, the wind or the bicyclist not pedaling harder?

31. October 2014 at 03:12

There’s a good article on FT Alphaville about Fed’s policy and inflation expectations. Quite funny to see that actual QE hasn’t had that much effect on expectations. As Scott likes to say practically nobody understands monetary policy, and I suppose it’s not very surprising.

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/2014/10/30/2024762/why-didnt-qe3-raise-inflation-expectations/

31. October 2014 at 05:10

excellent blogging sir.

31. October 2014 at 05:17

@Andy

“practically nobody understands monetary policy.”

The CNNMoney comments section begs to differ:

http://money.cnn.com/2014/10/31/news/economy/bank-of-japan-stimulus/index.html?iid=HP_LN

LOL, followed by uncontrolled weeping.

31. October 2014 at 05:47

We here a lot of talk about the Fed hurting savers to help those with debts.

I know there are a ton of counter-arguments, but I thought of one I haven’t heard before:

In early-2008, 5-year inflation expectations were at 2.5%. They thought that 100$ in 2008 would buy 113$ of goods and services in 2013. Loan contracts were signed with these expectations in mind.

Because of the Fed’s actions, who is essentially solely responsible for the level of inflation, this 100$ in 2008 ended up being worth 108$ in 2013. That’s a big difference in favor of the 2008 savers.

31. October 2014 at 06:02

Everyone, Thanks for the tips, and see my new post.

Kevin, I couldn’t tell whether the weekly benefits were larger, or extended for a longer period.

Name, That’s possible, but the welfare state I favor would speed growth up relative to our current system. So that’s the focus of my efforts. I have no idea what is ideal. I’m just trying to improve things.

Doug, Both supply and demand clearly matter.

BC, Charts show actual inflation, not the target. Actual inflation is sometimes above 2% and sometimes below. The target is slightly below 2%.

Andy, It raised them relative to no QE (i.e. the eurozone) but not in absolute terms.

LK, You said:

“We here a lot of talk about the Fed hurting savers to help those with debts.”

You are right that this belief is out there, but it’s almost comical given that the Fed’s tight money policy has hurt both, and it has hurt borrowers much more than savers.

31. October 2014 at 06:08

@LK, this only benefitted savers willing to risk that inflation came in under expectations, which is more like investors.

If you left money in the bank, you’ve lost 8% of your purchasing power over the last six years. I’m not sure what these savers “should” have earned, but historically, they have enjoyed something like a 1% real return annually on average.

I don’t think what’s happened to savers is necessarily a bad thing, but…

31. October 2014 at 06:44

@LK @Brian D.

Nice thinking. But the question remains did the savers lose more in purchasing power than they saved in low inflation.

More critically, I think some folks are suffering from economic cognitive dissonance. Some savers are wanting to get high real returns in a low inflation environment. Sorry, but the two can’t coexist together – like matter and anti-matter – and when they do it is only for very short spells.

Some debtors are suffering likewise – hoping for high inflation to inflate debt away but not wanting to lose purchasing power due to inflation. Both are fool’s errands.

31. October 2014 at 06:46

Scott: “BC, Charts show actual inflation, not the target.”

I was talking about the first chart, titled “Undershooting”, not the second, titled (Slippery Slopes). The inflation target is indicated by a white band between blue hash marks. Actual inflation is given by orange and red hash marks. The chart shows Euro area target as 0-2%, with the ECB hitting its target (in the sense of hitting the side of a barn). Sweden, Britain, US and Japan have precise targets of 2%; China precise target of 4%. The rest have target bands.

31. October 2014 at 07:41

Why is it bad for a central bank to have a large balance sheet? I mean besides the voodoo stuff.

31. October 2014 at 09:02

Scott, as far as I could tell, they are just looking at changing the rules of the Extended Benefits program, which is a standing program that provides a few extra weeks of partial benefits when there are regional unemployment shocks. The idea would be to use that standing program, but to make eligibility easier and to make payments more generous, compared to its current rules.

31. October 2014 at 10:45

There’s something I don’t understand about monetary offset: isn’t it a willful action that the Fed can avoid if they want to?

For comparison, imagine a more superstitious world than ours. The Federal Reserve Board may use conventional policies without limitation, but before undertaking unconventional policies, it must consult the Oracle of Dallas to ensure that the gods approve of the policy.

A financial crisis hits and the FOMC lowers interest rates to 0%, but they believe more aggressive measures are needed. They approach the Oracle of Dallas to ask permission to implement unconventional policies, but the Oracle refuses, claiming that the gods will send down a plague of hyperinflation if they go forward.

So the Fed finds itself at an impasse. It would like to implement a more aggressive monetary policy, but irrational beliefs about the consequences of its proposals prevent it from doing so. Seeing that the economy is in rough shape, the government implements fiscal stimulus. Would the Fed really offset it?

31. October 2014 at 12:54

BC, My mistake. That graph is simply wrong. That’s not the target.

Kevin, So now the President determines governments spending? I thought it was Congress. Obviously you are probably right, but that’s really sad.

And why didn’t Obama do this nine months ago?

Brent, Sure that’s possible, but very unlikely. More likely if the Congress had not done stimulus, the Fed would have done what it did in late 2012, but in early 2009.

31. October 2014 at 15:05

That article was so poorly written, I might hold judgment. Maybe the President believes in the Efficient Policy Hypothesis, and he has his advisors come in each day and tack polling results on the wall, then throws darts at it to decide what he’s going to announce.

When you get a chance please read my last 3 posts. I started going through the national income data and realized that the disequilibrium in the housing market is pushing down reported compensation.

1. November 2014 at 11:29

Agree with you Scott on monetary offset: I agree that the Fed has decided to pursue slower nominal growth than before. And I agree that the Fed’s signals about raising rates soon are not consistent with a central bank that has been frustrated by an inability to cut rates.

I would just say that the reason the Fed has chosen this slower growth path is QE and low rates. If rates were 5%, the Fed would have the US on a higher growth path. It’s not just unconventional policy they are averse to; it’s low rates – as in low by 90s standards, low by 70s standards seems ok!

The RBA is the same. They have allowed much slower growth in wages and NGDP since 2011 because they have been reluctant to keep cutting rates this time around. In recent times, they have basically signalled that they will not cut rates again, despite generational low growth in wages and sub-trend RGDP growth unless things turn quite dire. If rates were at 5.5% instead of 2.5%, I’m certain they would have cut a few more times over the last couple of years.

1. November 2014 at 14:57

Kevin, I’ll take a look.

Rajat, I guess there will always be new reasons why the Fed is so cautious. Your guess is as good as mine.

2. November 2014 at 06:17

“A bicycle rider has a “policy” of maintaining a steady speed of 15 miles per hour.”

Suppose the force on the bike pedals that is required to maintain that speed is physically unsustainable. Suppose the chain starts to skip, the bolts start to loosen and rattle, and the oiled bearings in the wheels start to release smoke.

Suppose the speed is then reduced. Thankfully.

MMs: “Hey! Don’t you know that suddenly slowing down like that is bad for business!?! And look at what slowing down has done to the bike! I didn’t see any smoke when you were going at 15. Now that you slowed down, I can see it! The bike is showing signs of breaking down now that you have slowed down. You should have kept going! Oh if only we had a speed targeting policy, like 15. Well, it doesn’t matter how fast it is, as long as it is constant. We can ignore the structure of the bike because…EMH. Oh, and slow bike advocates, just so you know: This is the slowest ride since the Hoover grand Prix.”

Reality: what MMs believed was all nice and sustainable, which is the speed if the bike, ignores the stresses on the bike needed to keep the bike at that speed. The whole time the bike was on its way to breaking down before it was intended to break down by the investors. As the bike is structurally damaged more and more at the too high speed, more and more pressure on the bike pedals is required to keep the bike at 15. More and more oil being applied to the bearings is delaying the breakdown, but the bike just cannot handle the stress needed to maintain a permanent speed of 15. 15 is becoming more and more a destructive speed policy.

MMs: “Hey! The Japanese racer’s team applied more oil to their racer’s bike even with the smoke and rattling, and very stressed bike rider, and they didn’t slow down as much as we did! Is this not proof that even when the bike is going slow, that more oil can always make it go faster?”

Reality: MMs don’t know how anyone can know the sustainable speed of the bike is, because they don’t understand bike structure theory. Any signs of bike structure failure that are correlated with a slow down in speed are always and only interpreted as the slow down causing the bike damage, rather than the other way around. After all, the oil men can make the bike go 200 with enough oil if they wanted!