Why no layoffs?

Six weeks ago I did a post on the puzzling fall in unemployment claims:

The new claims for unemployment this week was a shockingly low 320,000, bringing the 4 week average down to 332,000

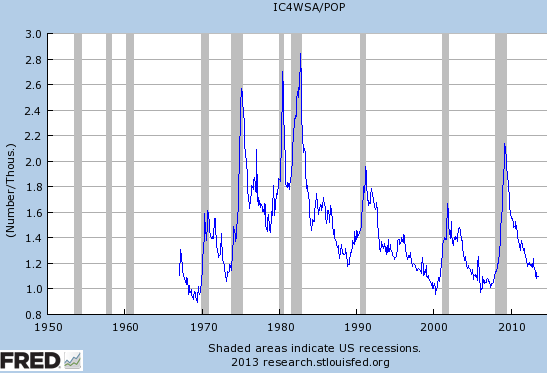

335,000, which is the lowest since October 2007. This graph shows the ratio of the 4 weeks average to US population (times 1000 to make it easier to read.)

The most recent week on the graph is at about 1.1, but today’s figures are at 1.049

1.058, if they were added. This means the ratio of new claims to pop is roughly back to the boom levels of 1999-2000 and 2006-07. And yet the other indicators (total jobs, unemployment rate, etc), remain deeply depressed.

I’m not going to redraw the graph, but with today’s numbers (308,000 on the 4 week average) we have fallen below the 0.1% level, meaning that fewer than 1/1000ths of Americans now file for unemployment comp each week. That’s not just boom conditions, it’s peak of boom conditions. The only other times this occurred since 1969 (when unemployment was 3.5%) were just a few weeks at the peak of the 2000 tech boom and a few weeks at the peak of the 2006 housing boom. In other words, the puzzle is now even greater than 6 weeks ago, as the unemployment rate is still at recession levels (7.3%.) Something very weird is going on in the labor markets.

I don’t have any good ideas. Perhaps employers are reluctant to add workers for some reason (Obamacare?) and instead work them overtime more. Then when demand falls instead of laying off workers, they cut overtime. But I don’t recall the average workweek numbers being all that unusual.

My hunch is that these new numbers portend further declines in the unemployment rate in the months ahead. Which is also a puzzle given that RGDP growth is about 2% in recent years.

PS. Part of the difference from 2000 is the lower LFPR, but even so, the current figures are shockingly low for a period of 7.3% unemployment

PPS. A Bentley student named Zachary Musso asked me to be interviewed on the Macro Tourist Hour, which he also participates in. Here is the link:

Unfortunately I am no good with technology, so you’ll only hear the audio from me.

PPPS. I was on panel at the Blouin Creative Leadership Conference in NYC on Tuesday. Perhaps there’ll be a link somewhere. One panelist said inflation was actually 7%.

I’ll try to get caught up with comments later.

Tags:

26. September 2013 at 06:23

I was thinking about this in the last couple of weeks.

The JOLTS report suggests that both job creation and job destruction are at lows. But what does this imply.

If all is going well, the most productive sectors of the economy will be adding workers and the least productive sectors will be shedding workers and this lifts overall productivity.

If the dynamics of this “creative destruction” is slowing, that then this suggest a slowing of productivity growth. If productivity growth is slow, then the RGDP growth trend and potential RGDP growth are slower today than in decades past.

26. September 2013 at 06:44

Four years after a recession has ended, ‘new claims’ should be in steep decline.

26. September 2013 at 07:02

Is this issue related to the presence of positive inflation through most of this recession?

26. September 2013 at 07:36

Did you catch Justin Wolfers piece on Bloomberg today?

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-09-26/where-is-the-panic-over-deflation-.html

26. September 2013 at 07:47

Maybe since there is so much long-term unemployment, a lot of the unemployed are no longer eligible for UI? Or maybe it has to do with a lot of the unemployed never having had a job (recent graduates, maybe) and therefore not being entitled to UI?

Just guesses.

26. September 2013 at 07:47

Scott,

Have you followed up on North Carolina’s claims data? It’s still looking interesting.

http://tinyurl.com/k4tayny

New claims have remained low and continued claims, after initially spiking, have started to fall dramatically as well.

26. September 2013 at 07:53

I think what this means is labor is on average more skilled and a lower part of the overall cost structure than in the past.. It also is a reflection of good corporate profits. Companies are loath to hire/fire because of the high cost of training so they are willing to ride out periods of low demand and high demand without changing employment.

26. September 2013 at 08:06

Prof. Sumner,

Here is a fascinating EconTalk with David Laidler:

http://www.econtalk.org/archives/2013/09/david_laidler_o.html

And here is Bob Murphy trying to use that interview to go after you:

http://consultingbyrpm.com/blog/2013/09/things-dont-look-good-for-those-fixated-on-aggregate-demand.html

26. September 2013 at 08:11

Perhaps employers are reluctant to add workers for some reason (Obamacare?) and instead work them overtime more.

This just what I would do if I owned a restaurant that was going to forced to buy health insurance for my employees. I would promote my best workers to assistant managers and raise their hours. The other workers I would keep part time and maybe hire some more. So I would want my best employees to work a lot of hours so i spread the cost of health insurance over more work hours and try to fill in the rest of the schedule with part timers whom I do not need to provide insurance.

26. September 2013 at 08:14

I agree with MikeF. An increase in government intrusion in the labor market has contributed to a less dynamic labor market.

And Scott, do you not pause anytime you benchmark data to October 2007? I would think any comparison to data from that month would give an economist pause. The future looked so bright in October 2007 yet it turned out not to be. Was there anything in the data that would have predicted the economic downturn that was about to hit?

26. September 2013 at 08:25

Here’s a Just-So story. The 2.5 main elements are (1) Multiple Equilibria (2) Surprisingly variable worker productivity post 2008 (2.5) Implicit Firm-Labor Bargaining.

Starting with (1). If the Fed for some reason wanted to create a world with stable but well below full employment (and/or lower LF participation), could it? This seems like it could be tricky to pull off as markets might actually adjust to the Fed and reach full employment in spite of it. An argument can be made that the Fed would have to create a reaction function that was not only asymmetrical (confidence the Fed will loosen upon an exogenous shock to get the stable part but won’t allow nominal dislocations to alleviate), but it might have to have its upside reaction function be constantly surprising the market to prevent creative adjustment among price bargainers to the predictable reaction function, even one seemingly too tight on the upside given the immediate situation. If the market became confident that the Fed was going to act if stuff really hit the fan, but was highly uncertain as to what the Fed was planning to do given various scenarios of more benign conditions, it’s possible to imagine a rut where idle resources stayed idle (actually mini-bouncing in an idle-like state) for a long time as the pricing game floundered amid a series of reaction function head fakes. This looks a little like today’s world, as we have just printed 0.6% core PCE with high unemployment and low LFP yet the big question today is when the Fed will tighten, whereas the Fed and even ECB seem to have convinced markets that they will start buying TSLA if the Euro crisis or other sunspot pops up.

Second, you have this seemingly extreme phenomena where worker productivity among the non-laid off really appeared to have popped more than many might have expected after 08-09 and seem to have retained these one-time gains. The morale costs of even normal layoffs among what may be seen as a more valuable but perhaps fragile remaining workforce might seem unusually high if there is an implicit bargain that workers who suffered fears of layoffs coupled with having to work harder for no additional compensation did so with an implied promise that they were being spared additional layoff risk. The marginal costs of layoffs might be higher than usual for the morale and productivity of those not laid off.

So good downside reaction functions and thus no additional nominal fear means no monetary policy induced layoffs + constant throttling by the Fed as to its upside reaction function keeping markets from getting to a FE equilibrium + uniquely high costs to layoffs to firm given recent history = low hiring + very low layoffs. Just a story.

26. September 2013 at 08:28

Doug, Good point. Great Wolfers column.

Patrick, Yes, but given the anemic recovery, it is rather surprising to see claims so low.

LK, That might be related.

Mark and Mike and Floccian, Good points.

Travis, Bob quotes Cochrane as evidence against my view. I guess he doesn’t know that I already did a post praising that quotation.

Laidler probably isn’t aware of the MM argument for NGDP targeting, those objections have all been addressed.

Cameron, Yes, very interesting.

26. September 2013 at 08:31

Dan, Downturns are unpredictable, economists pretty much agree on that point. So it’s not surprising that the data in 2007 did not predict a downturn.

26. September 2013 at 08:53

[…] 6. Why no layoffs? […]

26. September 2013 at 09:21

Kocherlakota’s new speech:

http://www.minneapolisfed.org/news_events/pres/speech_display.cfm?id=5168

Read the whole thing.

26. September 2013 at 09:25

The companies I work with, 25 to 150 employees, have taken a investment in productivity capital and attrition strategy. Bring in labor saving capital and then reduce your work force through attrition.

That means released workers are never counted at unemployees either because the have a new job or are retiring.

If my relatively small skewed sample is reflective of business in general the decline in first time unemployment makes sense.

26. September 2013 at 09:30

Why layoffs falling so low? I work in an office environment and hear are my views:

1) We live in a productivity focus economy and it costs a lot more to back fill position than years ago and workers have not been able to leave as easily.

2) All the layoffs were in 2008 and 2009

3) There is no more opportunity of back rooms going to India. In fact, it is point where companies are so lean in the US offices have no back up talent. Backroom talent in India can not simply step in customer facing jobs and offices.

26. September 2013 at 09:53

dlr, Mike and Collin, Those are all good ideas.

Saturos, Great stuff! Thanks.

26. September 2013 at 11:02

Many of the companies I consult for are not hiring externally. There are many open positions as different areas of the firm have grown or not over the the past six years but those openings must be filled with internal transfers,

(Btw, I’m talking about very large companies with 10-100k employees.)

The executive perception presented with these strictures is that growth is okay but expected to be slow in the economy overall for the next couple years still.

26. September 2013 at 11:17

Where does the FRED data come from? If it comes from the BLS it may be tainted. Interesting article here…

http://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2013/09/how-bad-data-warped-everything-we-thought-we-knew-about-the-jobs-recovery/279923/

26. September 2013 at 11:31

With all the confusion about the taper, and signals in all directions from FOMC-members, maybe this time the explanation truly is uncertainty?

An informal argument: the most natural thing to do when there is a lot of uncertainty is to postpone the decision until there is more information. In this case the relevant decisions are about hiring and firing. If decisions about both are postponed, in general, you get a slowly decreasing unemployment rate and no new unemployment claims.

26. September 2013 at 11:37

[…] Scott Sumner comments on the initial claims release: “Why no lay-offs?”: […]

26. September 2013 at 12:04

Tyler Cowen says Krugman is our Milton Friedman. Very fascinating. I’d venture to say that Obama is the left version of Reagan, he will be remembered as a champion of liberalism. Yet those of us who remember will remember a fairly centrist guy when it came to military, surveilance, and spending cuts.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=ZDxcURE7sJs

26. September 2013 at 13:30

Daniel J:

Reagan left office with an approval rating of 63% On Sep 16, 2013 Obama’s rating is 43%. If Obama was to leave office with a 60% approval rating that would beg a comparison to Reagan as a dramatic improvement in the economy and the political feeling would have occurred.

And while Obama has been very centrist in doubling down on George W. Bush’s national security policies there has never been a president like Obama who has personalized national politics and demonized his political foes. The left hated GWB but he rarely, if ever, reciprocated. Obama on the other hand is a polarizing politician and he goes out of his way to create political divides.

Reagan, on the other hand was very successful in creating bipartisan support for his legislation. Even his tax and budget plans were bipartisan efforts.

In other words, it is very unclear at this point in time that Obama can be said to be the left’s version of Reagan. A Nixon comparison is more like it. The left’s best version of Reagan was Clinton. Alas, Clinton was a centrist, if not libertarian concerning economics and fiscal policy.

26. September 2013 at 14:30

People have stable future-value-of-money and income expectations (i.e. stable + positive on both). So, why would we expect significant sackings?

Is this “boom” conditions, or (stable+positive) expectations?

26. September 2013 at 18:49

Here, ssumner uses the initial claims per population. But, I’ve long wondered why, and always considered a bit odd, that almost all other economists prefer to use the absolute number for analysis. Does anybody know why ?

26. September 2013 at 19:11

Regarding Japan…yes different culture, economy…but did they reach point little layoffs, but little growth…steady state perma-sluggishness? You can’t get laid off if you were never hired…businesses went to lean staffs but never laid anyone off…unemployment drops as claims are exhausted…

26. September 2013 at 21:47

A proposed SOLUTION to the Nation’s biggest problem, unemployment.

The Dept. of Labor should change the standard workweek to 30 hours,

It has been at 40 hrs for many years in spite of: productivity

improvements, not passed on to workers, extended to services by

the introduction of computers and by the doubling of the available

workforce by women wishing to work.

Unions worked ceaselessly to shorten the standard workweek since

our transition from an agricultural economy to industrial. The result

would be a 12% increase in pay & govt. revenue until employers hire

additional workers””which is the desired goal””full employment.

Industry and Education would benefit by working 60 hours per week

with no increase in facilities or fixed costs.

College students would benefit by fulltime class and earning a full time

salary, paying their own tuition and graduating with work experience

Instead of debt.

Infrastructure will be improved by 17% less traffic, easing state and

local expenditures.

Less traffic will save dollars, fuel costs, and wasted time for everyone.

This is a no cost solution to numerous problems with universal appeal !

27. September 2013 at 01:00

[…] Scott Sumner at The Money Illusion expresses his amazement and confusion at these numbers: […]

27. September 2013 at 01:40

[…] Scott Sumna at Da Dead presidentz Illusyun exprezzez dude amazemint an' confusyun at deez numberz: […]

27. September 2013 at 05:16

We have reached Keynes’s unemployment equilibrium.

27. September 2013 at 06:32

[…] Scott Sumner raises the issue. […]

27. September 2013 at 09:06

Simon, There was a lot of uncertainty in 2007-09, I don’t see much uncertainty today. RGDP growth will be 2% and inflation will stay low.

Daniel, Thanks for the link, but Obama is merely a caretaker President, not a transformational figure like Reagan.

Lorenzo, But wasn’t the same true in 1995? Why are claims so much lower today?

27. September 2013 at 11:41

productivity improvements, not passed on to workers,

Investing money in order to pay someone more is not a sound business model. And why would you expect more productivity to lead to less hours rather than more production?

Also, you seem to be forgetting the small problem of a ~10% drop in GDP as less work gets done. That’s hardly “no cost.”

27. September 2013 at 14:31

But wasn’t the same true in 1995? Why are claims so much lower today?

Good question. In fact, the real question is why there has been the most sustained and close-to-the-steepest fall in new claims in decades? Did extending the period of UI reduce the amount of “cycling through”? I.e. people temporarily getting new jobs before going back on UI.

I am not expert in US UI rules, but I would also look at rate of entry into the labour market–what is happening with labour force participation? We are looking at a specific factor market, so it is always good to look at both general macro conditions and specific institutional/demographic factors.

27. September 2013 at 21:08

Dear Scott,

I would think your denial of uncertainty is at at odds with your own worries about the effects of different Fed policy for the recent months.

Ifthere is no uncertainty about growth, then why did markets respond so strongly to the recent FOMC meeting? Also, why did you say ‘we dodged a bullet’ when Larry Summers declined his candidacy for Fed Chair?

The difference with 2007-2009 might be explained by the different stages of the recovery, but I agree that’s a weak argument.

27. September 2013 at 23:50

Unemployment tracks pretty closely with continued claims also.

http://idiosyncraticwhisk.blogspot.com/2013/09/unemployment-insurance-claims-and.html

Right now, insured unemployment is about 2.8 million, or 1.8% of total labor force. EUI unemployment is about 1.35 million, or .9% of total labor force. If you add EUI to normal continued claims, the UER is tracking right along with the current total level of insured unemployment.

The good news is that EUI is continuing to shrink with a fairly linear trend of about 800,000 per year, so this along with recent declines in initial claims and continued claims could mean that UER continues along its present trend or even accelerates down.

28. September 2013 at 08:32

Lorenzo, You asked:

“Did extending the period of UI reduce the amount of “cycling through”? I.e. people temporarily getting new jobs before going back on UI.”

Excellent question, I had not thought of that.

Simon, You misread my comment. I did not say there was no uncertainty, just a small amount. The stock move after Summers left (an implied swing of perhaps 2%) confirms that Summers was only a mild negative, after all, he was just one vote out of 12.

kebko, Yes, it’s the new claims that seem mysterious.

28. September 2013 at 13:01

Almost 25 years ago, I used to work in a labour market analysis area of the Australian public service in Canberra.

28. September 2013 at 16:43

Sir,

There is a very simple explanation for this phenomenon: the majority of jobs created in the recent past have been temporary jobs, see here: http://johnrlott.blogspot.com/2013/09/stunning-96-percent-of-net-jobs-added.html

and…most temporary workers are ineligible for unemployment benefits, so… you see so-called “shockingly low unemployment numbers.”

Not really.

28. September 2013 at 16:56

Phillip, I generally ignore commenters who lie about what I’ve said in a post. If you put something in quotes, you better make sure it is exactly what I said, or at least equivalent.

Otherwise your comment is useless, as the 96% net figure on new hires has no bearing on layoffs.

28. September 2013 at 20:32

Scott,

I get the feeling that most folks think it is somewhat unlikely that we will see a policy change in the October meeting.

But, we are at 7.3% unemployment right now. There is a sizeable possibility that unemployment could hit 7.0% before the December meeting, especially if UI claims continue to show strength. That would be quite a piece of information for the bond markets to deal with, if unemployment hits 7.0% before the Fed even starts tapering….

29. September 2013 at 05:42

kebko, Bernanke made a mistake talking about the 7% threshold. He should have focused on whether the Fed needed to do more or less to hit their mandate.

30. September 2013 at 06:01

Sir,

I don’t understand your anger directed at me as I was not challenging anything you said but was merely providing my opinion of what is happening (perhaps you detected a sarcastic tone where there was none)… I’m not sure why you took it personally. And I was merely quoting from the blockquote above.

Also, to your point that my point has no bearing on new layoffs, I disagree, as I used that link merely to illustrate a point: most of the hires in recent years have been temporary workers and as they are ineligible for unemployment insurance, over time all claims will fall, no?

Thanks, pb~

1. October 2013 at 04:39

Phillip, Sorry if I overreacted. I don’t like it when people misquote what I say and do so in a way that makes me look stupid. I didn’t say what you quoted me as saying. and if I had I would’ve been stupid. Obviously it would be absurd to claim the unemployment rate in the US is shockingly low.

1. October 2013 at 06:35

“I don’t have any good ideas. Perhaps employers are reluctant to add workers for some reason (Obamacare?) and instead work them overtime more. Then when demand falls instead of laying off workers, they cut overtime. But I don’t recall the average workweek numbers being all that unusual.”

Here’s an old idea:

“In particular, it is an outstanding characteristic of the economic system in which we live that, whilst it is subject to severe fluctuations in respect of output and employment, it is not violently unstable. Indeed it seems capable of remaining in a chronic condition of subnormal activity for a considerable period without any marked tendency either towards recovery or towards complete collapse. Moreover, the evidence indicates that full, or even approximately full, employment is of rare and short-lived occurrence. Fluctuations may start briskly but seem to wear themselves out before they have proceeded to great extremes, and an intermediate situation which is neither desperate nor satisfactory is our normal lot.

We certainly seem to have been in a “chronic condition of subnormal activity for a considerable period without any marked tendency either towards recovery or towards complete collapse.” and maybe Keynes is right that “the evidence indicates that full, or even approximately full, employment is of rare and short-lived occurrence.”

The economy is a new profiable equilibrium at that needs fewer workers and less labor participation neither hiring more nor laying off less. Hence, we are seeing “the ratio of new claims to pop is roughly back to the boom levels of 1999-2000 and 2006-07.”

With or without the ACA, assuming no significant overtime wages, it is always marginally less costly to work current workers longer than to hire new ones.

These low layoff tell me we are at some sort of subnormal equilibrium. We are humming along profitably along at 95% of potential GDP.