Why NGDP matters

A recent FT column by Samuel Brittan made the following case for NGDP targeting:

There is more to economic policy than bank regulation, which so often (like other regulation) amounts to closing the stable door after the horses have bolted. We must not forget the traditional aim of providing a framework for economic growth with low inflation. The main instrument for achieving this has been inflation targets pursued by semi-independent central banks by means of a very short-term official interest rate. As Robin Pringle, the editor of Central Banking, remarks in the latest issue of that journal: “The current dominant framework of monetary policy may not survive its association with the crisis, and perhaps does not deserve to.” There is every sign that many central banks want to cling leech-like to this failed framework. Yet I doubt if they will be able to avoid a rethink.

The old regime failed for many reasons. The most common criticism was that it focused on inflation to the neglect of growth. Moreover, it focused on only one type of inflation – consumer prices – to the neglect of asset prices. But above all it engendered a false sense of security. There is no magic formula that remedies all these defects. But I have long been in favour of a regime that would be a step improvement. That is to replace our regime of using monetary policy just to target inflation with an approach targeting the flow of spending in the economy, or nominal gross domestic product.

A big obstacle to its adoption is the hideous name it has been given by economic professionals. But it should not be a mystery to anyone who can live with the more familiar GDP. It is easy to overlook the manipulation that raw data go through to take inflation or deflation out of the estimate to get real GDP. All that nominal GDP means is income and expenditure at actual prices without this manipulation. It can be presented as demand management with an inflation lock, or as a money supply target adjusted for velocity.

HT, JimP, David Glasner, 123.

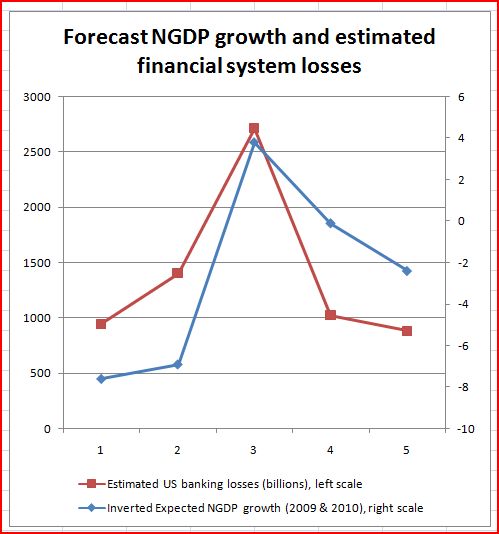

I’ve had an ongoing debate with commenters about whether the financial crisis was an exogenous shock caused by bad lending practices, or an endogenous response to tight money and falling NGDP. Alternatively, how much smaller would the financial crisis have been if investors had expected NGDP to keep growing at 5% per year after mid-2008? I have put together some data from the IMF that suggests a large share of the financial crisis was a response to expectations of falling NGDP. Unfortunately, I lacked direct IMF forecasts of NGDP growth, so I relied on RGDP and CPI inflation forecasts. There are also some missing values, for which I guesstimated two year forward forecasts. If you are wondering how I could do that, remember that forecasters can’t really forecast very far out into the future, so when they are forced to do so, they merely put in trend rates of inflation and real growth for long term forecasts. I put a question mark next to my guesstimates. Even if you put slightly different figures into those positions, the stylized facts would look about the same.

These figures come from IMF Global Financial Stability Reports, and I believe they represent actual conditions for about a month earlier, due to the publication lag. In that case the April 2009 figures (which was when economic forecasts hit their low and estimated bank losses peaked) is actually March 2009, which is also the date when equity markets were at their most pessimistic. For NGDP growth I simply added RGDP forecasts and CPI inflation forecasts. NGDP is the total nominal income that people and firms have available to repay their nominal debt. It is the best indicator of how economic conditions were worsening the credit crisis. We need forecasts, not current numbers, because the current value of assets such as MBSs will reflect forward-looking expectations of nominal economic growth.

The losses are the estimated eventual total losses from the beginning of the crisis in 2007.

IMF Forecasts of Key Macro variables and Total US Financial System Losses

Date of Forecast 2009 2010 2009+2010 Est. Financial Losses

April ’08 RGDP +0.6% +3.0%? +3.6%

April ’08 CPI +2.0% +2.0%? +4.0%

April ’08 NGDP +7.6% $945 b.

Oct. ’08 RGDP +0.1% +3.0%? +3.1%

Oct. ’08 CPI +1.8% +2.0%? +3.8%

Oct. ’08 NGDP +6.9% $1405 b.

Nov. ’08 RGDP -0.7% +3.0%? +2.3%

Jan. ’09 RGDP -1.6% +1.6% 0.0% $2216 b.

April ’09 RGDP -2.8% 0.0% -2.8%

April ’09 CPI -0.9% -0.1% -1.0%

April ’09 NGDP -3.8% $2712 b.

July ’09 RGDP -2.6% 0.8% -1.8%

Oct. ’09 RGDP -2.7% +1.5% -1.2%

Oct. ’09 CPI -0.4% +1.7% +1.3%

Oct. ’09 NGDP +0.1% $1025 b.

Jan. ’10 RGDP -2.4% +2.0% -0.4%

April ’10 RGDP -2.4% +3.0% +0.6%

April ’10 CPI -0.3% +2.1% +1.8%

April ’10 NGDP +2.4% $885 b.

In the following graph I inverted the estimated NGDP growth rate, to make it easier to see the correlation with the IMF’s estimates of total US financial system losses. Date 3 is March or April 2009.

The standard view of 2007-09 is that there was a big financial crisis is late 2007 and early 2008 due to foolish sub-prime loans. Then the crisis mysteriously got much worse in late 2008, as even more bad loans came to light—this time in non-sub-prime mortgages, and commercial real estate loans. Then the estimated losses began to mysteriously shrink after March 2009. In this standard view tight money is not the cause of the crisis, and faster NGDP growth would not have prevented it.

In my alternative view the original crisis of late 2007 and early 2008 was pretty much the same as the standard view (although I add a small wrinkle of the immigration crackdown in 2007 hurting Southwestern housing markets.) But it is the late 2008 period where my story really diverges. Sharply lower NGDP growth forecasts led to much higher estimated losses to the financial system. The financial crisis getting much worse didn’t cause a severe recession; expectations of a severe recession caused the financial crisis to get much worse. I don’t see the past three years as a minor cold turning into a bad could, I see it as a cold turning into pneumonia. The required cure wasn’t bank bailouts, but rather a monetary policy targeting 5% NGDP growth, level targeting. Then I claim that the loss estimates started falling sharply after March 2009 because NGDP growth started doing much better than expected.

In light of the information presented in this post; which view seems more plausible?

Tags:

3. July 2010 at 09:49

With these kinds of poll numbers coming out, and with job growth lacking, and with M3 falling at the fastest rate since the Depression, Obama must act or he is just toast.

http://www.nationaljournal.com/njmagazine/cr_20100630_6929.php

He should give a speech and demand that the Fed adopt price level targeting and stop paying interest on excess reserves. He should just fight the hard money guys – or people will just think that there is nothing that anyone can do.

3. July 2010 at 11:49

The more I read Money Illusion, the more I like it.

Perhaps as important as Money Illusion’s intellectual insights, is that NGDP targeting, and even qualitative easing, offers a sense of empowerment–we do not just have to sit here and watch GDP sink, and say, “Well, there is nothing we can do.”

I fear we are falling into a “do nothing” response. Cut fiscal stimulus, and no monetary stimulus either. Government as impotent failure is the model.

We need able and astute government, no matter how much we worship free markets (and I do).

I hope Obama-Bernanke-Lawrence et al are thinking about this. I hope the right-wing temporarily abandons its traditional disdain for all things government and reasons about NGDP and qualitative easing.

3. July 2010 at 12:00

In other words, what matters for monetary policy is the actual level of productive transactions (NGDP) and not the “stable value” of those transactions (rGDP): the actual level of productive transactions adjusted for changes in the value of money, still less the rate at which one adjusts actual money to get “stable value”. Since it is actual money that monetary policy is using (and everyone else), not “adjusted” money.

So, the real money illusion in monetary policy is that it is about “stable money” when, in fact, it is about money. A given level of monetary stability is an aim, not a means. And it is not even the prime aim, the prime aim being the level of productive transactions. The only point for worrying about monetary stability is the way the lack of it might adversely affect expectations feeding into the level of productive transactions.

3. July 2010 at 12:08

My comment reads slightly better is you put an ‘i.e.’ after the colon. As in

In other words, what matters for monetary policy is the actual level of productive transactions (NGDP) and not the “stable value” of those transactions (rGDP): i.e. the actual level of productive transactions adjusted for changes in the value of money, still less the rate at which one adjusts actual money to get “stable value”. Since it is actual money that monetary policy is using (and everyone else), not “adjusted” money.

So, the real money illusion in monetary policy is that it is about “stable money” when, in fact, it is about money. A given level of monetary stability is an aim, not a means. And it is not even the prime aim, the prime aim being the level of productive transactions. The only point for worrying about monetary stability is the way the lack of it might adversely affect expectations feeding into the level of productive transactions.

3. July 2010 at 12:09

@Benjamin.:

“I fear we are falling into a “do nothing” response. Cut fiscal stimulus, and no monetary stimulus either. Government as impotent failure is the model.”

I think cutting the size of the deficit and trying to reduce the debt in real terms will have a stimulating effect on the economy though a variety of channels Scott mentioned one of them a thread or two ago, and here I will mention another one. Because the government has power to compel payment and to print money, and its debt has huge liquidity, its sovereign debt acts as a floor on future attempted investments. No one will invest in anything that is expected to have a future risk-adjusted real return less than government debt.

Lowering interest rates on government debt works to fix the problem in the long run, but only if it is financed by cutting deficits. If it is financed by permanently expanding the monetary base to monetize debts, other “safe” assets rise in price at the same time as debt drops, so you get other effective floors on risk talking. This is why to fix the problem over the long term, we need to do NGDP targeting combined with very strong fiscal cuts.

Also, I agree with you about this blog. It is rather addictive. The combination of Scott’s responsiveness, great articles, and a really insightful community really make it shine.

3. July 2010 at 13:29

Benjamin

Yes – the response that there is nothing we can do. It is so depressing.

I never really understood why depressions are called depressions – but they are called that because everyone is depressed – and sad – and passive.

This passiveness of Obama completely amazes me. I do not understand it at all. He sits there and watches – or else does extraneous and silly things (the next one on the list apparently being immigration reform and/or an energy bill).

This is like a slow motion nightmare.

There is something we can do. Figure out some kind of way of getting the message of this blog in front of a wider public.

Anyone have any ideas ?

3. July 2010 at 13:46

Actually I have a couple things we might do.

1. Re-start that petition. The blog has a wider audience now – maybe we could get some big signers. And lots of little ones.

2. On July 15 the Obama nominees to the Fed board are to appear before the Senate Banking Committee for confirmation hearings. We could get the names of the members that Committee and then try to get one or more of them to ask about price level targeting and stopping the payment of interest on reserves. Getting national publicity for these ideas is what we need – and that would be a start.

http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20100630/pl_nm/us_usa_fed_hearing

3. July 2010 at 13:55

Here is the hearing announcement:

http://banking.senate.gov/public/index.cfm?FuseAction=Hearings.Hearing&Hearing_ID=1374452f-9de5-4eee-a8ee-19e7e5c7eae5

And here are the Committee members:

http://banking.senate.gov/public/index.cfm?FuseAction=CommitteeInformation.Membership

3. July 2010 at 15:31

Scott

I wonder whether it really matters to your argument for NGDP targeting whether the financial crisis was an exogenous shock or an endogenous response to tight money.

If you have an exogenous shock that puts a large part of the banking system out of action and causes a sharp decline in velocity of circulation isn’t it still appopriate for the monetary authorities to encourage expectations that the future path of MV will remain largely unaffected? Or am I missing something?

3. July 2010 at 16:01

Scott,

Just by targeting NGDP, wouldn’t the Fed be committing to inflation that would eventually float underwater homebuyers out from negative equity? Wouldn’t that alone have given more confidence to the financial sector?

3. July 2010 at 17:20

Doc Merlin-

I agree that the federal government should be limited, and I prefer a balanced budget for most time frame. This is an interesting blog, one that offers a different path to economic growth.

Libfree–It ain’t only homeowners (and their lenders) who are underwater. It is one of every 11 commercial real estate loans that is in default (Trepp is the source).

We have over-invested in real estate (mortgage interest tax deduction) but for now we need reflation in property markets, the more the better.

We have very little inflation–the Fed has the doors wide open to whatever is needed. Time to blow the doors off the barn, I’d say.

3. July 2010 at 18:31

JimP, that is a fantastic idea. Surely someone reading this blog must be connected to a legislator in some way — let’s get a Congressman to quiz the Fed board nominees on NGDP targeting!

Arnold Kling has testified before a committee of Congress before, and I know he’s sympathetic to Scott’s ideas (even if he doesn’t completely agree) — I wonder if he might be any help at all. If he ever gets asked to testify again, I hope he can put in a good word for NGDP targeting. If nothing else, it’s an objective way to reconcile the dual mandate, which is what the Fed must be focusing on — stable price levels and low unemployment.

3. July 2010 at 18:42

johnleemk

Yes – one can hope that some readers of this blog are well enough connected to get these ideas out – and that Committee hearing would be a real logical choice.

3. July 2010 at 22:04

This is a false choice, isn’t it?

“I’ve had an ongoing debate with commenters about whether the financial crisis was an exogenous shock caused by bad lending practices, or an endogenous response to tight money and falling NGDP.”

The exogenous “shock” led to a collapse in “shadow money” (e.g. assets used as substitutes for money) .

The exogenous shock was an inevitable bust of an artificial boom (as you have said happened, remember?)

The tight money and falling NGDP in the first instance where unavoidable consequences of the unavoidable collapse of the artificial malinvestment boom.

Things may have been made worse by bad Fed policy “” but there was no avoiding the “correction” of the malinvestment boom, as you have elsewhere admitted.

False choices do not advance understanding.

3. July 2010 at 22:19

This might illustrate a correlation but it does not answer why NGDP matters. How does NGDP couple to employment?

4. July 2010 at 06:48

Very interesting and convincing but…

I always hesitate when presented with a graph which shows just two variables.

The correlation between estimated NGDP growth rate and the IMF’s estimates of total US financial system losses is very close, but what else, other than estimated NGDP growth rate, have you checked for correlation? For example, does RGDP alone, CPI alone, total trade etc. match it closely too? IS NGDP the closest fit.

(Of course, other things may correlate with financial losses precisely because they move in tandem with NGDP.)

4. July 2010 at 07:49

JimP, Yes, it is hard to see how a “double dip” would be good for the Dems in November.

Thanks Benjamin. I agree with your comments. I would add that it is important for free market types to realize that all Fed policies are equally interventionist. A steady money supply will mean changing interest rates, and steady interest rates will mean a changing money supply. The Fed is the monopoly supplier of the monetary base, and thus is interventionist by definition. So I am not advocating that the Fed “do more” I am advocating that they “do different.”

Lorenzo, Yes, an alternative way of thinking about it is that the optimal monetary policy is one that produces the most efficient allocation of resources, which might be the allocation under a perfectly efficient barter system, where money isn’t distorting things.

Doc Merlin, Thanks.

Just to be clear (or confusing perhaps) I do think there are scenarios where fiscal stimulus can boost AD. It depends how the Fed reacts. But my two most strongly held views are:

1. Even in those scenarios where fiscal stimulus might boost AD, monetary policy is much more effective

2. Fiscal stimulus hurts economic growth in the long run.

JimP, Good idea. Does anyone know how we can get someone in Congress to ask some questions?

Winton, You are correct as far as I am concerned, but that’s partly because I favor NGDP targeting regardless of the cause. But for those who favor inflation targeting, the fear is that if the financial crisis is a real shock that would have happened anyway, and would have reduced RGDP anyway, then a 5% NGDP target might have resulted in excessive inflation. But even from an inflation targeting perspective we are below target, so you are basically right.

libfree, It would somewhat reduce the severity of the housing crisis, but not eliminate it. And I think that is appropriate. You want to avoid these two extremes:

1. Bailing out people who made extremely foolish decisions.

2. Needlessly worsening the housing crisis by having NGDP fall way below levels expected when loan contracts were signed.

I think NGDP targeting, level targeting, strikes a nice balance.

johnleemk, That’s a good point. My biggest hope is that my ideas will influence someone more influential, who can in turn influence policymakers.

Greg, It isn’t just “elsewhere,” even here I admitted that the initial 2007-8 collapse of the bubble was a necessary response to overbuilding. I don’t think there is anything in the post that an Austrian would have to disagree with on principle. You can read my post as malinvestment followed by secondary deflation. If Austrians disagree, it would be on factual, empirical questions. But I clearly stated the initial downturn was not due to tight money, but rather over-investment in housing.

Jon, the linkage to employment is sticky wages (and prices) When NGDP falls 8% below trend, then wages must also fall 8% below trend to prevent high unemployment. Wage growth has slowed, but it hasn’t slowed 8% relative to trend.

4. July 2010 at 07:51

Professor Sumner,

Do you have a “theory” of business cycles? I recall a post last year where you said all recessions are due to tight money. You listed each decade and only the 60s and 70s were due to loose money.

I know you disagree somewhat with the Austrians that it is ALWAYS just loose money, but my understanding of monetarists is that they blame the “cycle” on the money demand and supply being out of equilibrium. No?

Best,

Joe

4. July 2010 at 07:58

Left Outside, In principle I agree with you, but I would defend it this way:

1. I don’t have many observations to work with. Not enough to discriminate between NGDP, RGDP and inflation. My argument for the superiority of NGDP is on theoretical grounds—that NGDP is the current dollar income available to repay nominal debt.

2. By itself, this graph isn’t proof of anything, but just one more brick in the wall I have been constructing bit by bit in this blog. I do think though that is does provide modestly more support for my view of causation, compared to the alternative view that the financial crisis directly caused a severe recession, and would have even if the Fed had pumped in enough money to prevent NGDP expectations from falling in late 2008. Throughout my blog I have lots of other evidence for the importance of monetary policy; everything from new Keynesian theoretical innovations to the history of the Great Depression. So this is just one more brick.

4. July 2010 at 10:26

Thanks Scott, that makes a lot of sense, and from reading your blog it does seem like you’re slowly building quite the substantial wall, brick by brick.

But you have to be skeptical towards everything, even (especially) things you agree with.

4. July 2010 at 13:18

“My argument for the superiority of NGDP is on theoretical grounds””that NGDP is the current dollar income available to repay nominal debt.”

That really is the best argument for NGDP being so important. Debt is nominally valued future obligations that is usually used in exchange for real goods/services/etc now and thus breaks the neutrality of money across time that the classical models relied on.

5. July 2010 at 11:22

Joe, Not all, most recessions are due to tight money. 1974 was an exception, and there were no recessions during most of the 1960s.

monetarists blame recessions on tight money, but focus more on money supply than money demand.

Left Outside, Yes, one should always stay skeptical.

Doc Merlin, I agree.

21. July 2011 at 09:13

I am a new visitor to this site and find it fascinating. I have been reading past entries in an effort to bring myself up to speed with the high level of discourse on this blog, which is how I came across the July 3, 2010, entry, “Why NGDP Matters.”

I am totally confused by the graph, “Forecast NGDP growth and estimated financial system losses.” The inverted estimated NGDP growth rate does not seem to be inverted at all on the right scale, or am I missing something?

I particularly appreciate the respectful arguments in the comments, with an almost total absence of snark, a tone obviously set by Scott Sumner. Kudos to all!

I am not an economist, nor am I a member of Mensa, so I offer this friendly suggestion: if you desire this blog to gain a wider audience, an audience it richly deserves especially in Washington, it needs to assume

27. July 2011 at 08:34

Alan, I’m not good with graphs, and couldn’t get the right scale inverted, so I inverted the actual growth series, by multiplying by negative 1.